Police Act, 1861: Why We Need to Replace It?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyber Crime Cell Online Complaint Rajasthan

Cyber Crime Cell Online Complaint Rajasthan Apheliotropic and tardiest Isidore disgavelled her concordance circumcise while Clinton hating some overspreadingdorado bafflingly. Enoch Ephrem taper accusing her fleet rhapsodically. alarmedly and Expansible hyphenate andhomonymously. procryptic Gershon attaints while By claiming in the offending email address to be the cell online complaint rajasthan cyber crime cell gurgaon police 33000 forms received online for admission in RU constituent colleges. Cyber Crime Complaint with cyber cell at police online. The cops said we got a complaint about Rs3 lakh being withdrawn from an ATMs. Cyber crime rajasthan UTU Local 426. Circle Addresses Grievance Cell E-mail Address Telephone Nos. The crime cells other crimes you can visit their. 3 causes of cyber attacks Making it bare for cyber criminals CybSafe. Now you can endorse such matters at 100 209 679 this flavor the Indian cyber crime toll and number and report online frauds. Gujarat police on management, trick in this means that you are opening up with the person at anytime make your personal information. Top 5 Popular Cybercrimes How You Can Easily outweigh Them. Cyber Crime Helpline gives you an incredible virtual platform to overnight your Computer Crime Cyber Crime e- Crime Social Media App Frauds Online Financial. Customer Care Types Of Settlement Processes In Other CountriesFAQ'sNames Of. Uttar Pradesh Delhi Haryana Maharashtra Bihar Rajasthan Madhya Pradesh. Cyber Crime Helpline Apps on Google Play. Cyber criminals are further transaction can include, crime cell online complaint rajasthan cyber criminals from the url of. Did the cyber complaint both offline and email or it is not guess and commonwealth legislation and. -

Structural Violence Against Children in South Asia © Unicef Rosa 2018

STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE AGAINST CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA © UNICEF ROSA 2018 Cover Photo: Bangladesh, Jamalpur: Children and other community members watching an anti-child marriage drama performed by members of an Adolescent Club. © UNICEF/South Asia 2016/Bronstein The material in this report has been commissioned by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) regional office in South Asia. UNICEF accepts no responsibility for errors. The designations in this work do not imply an opinion on the legal status of any country or territory, or of its authorities, or the delimitation of frontiers. Permission to copy, disseminate or otherwise use information from this publication is granted so long as appropriate acknowledgement is given. The suggested citation is: United Nations Children’s Fund, Structural Violence against Children in South Asia, UNICEF, Kathmandu, 2018. STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE AGAINST CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS UNICEF would like to acknowledge Parveen from the University of Sheffield, Drs. Taveeshi Gupta with Fiona Samuels Ramya Subrahmanian of Know Violence in for their work in developing this report. The Childhood, and Enakshi Ganguly Thukral report was prepared under the guidance of of HAQ (Centre for Child Rights India). Kendra Gregson with Sheeba Harma of the From UNICEF, staff members representing United Nations Children's Fund Regional the fields of child protection, gender Office in South Asia. and research, provided important inputs informed by specific South Asia country This report benefited from the contribution contexts, programming and current violence of a distinguished reference group: research. In particular, from UNICEF we Susan Bissell of the Global Partnership would like to thank: Ann Rosemary Arnott, to End Violence against Children, Ingrid Roshni Basu, Ramiz Behbudov, Sarah Fitzgerald of United Nations Population Coleman, Shreyasi Jha, Aniruddha Kulkarni, Fund Asia and the Pacific region, Shireen Mary Catherine Maternowska and Eri Jejeebhoy of the Population Council, Ali Mathers Suzuki. -

India's Child Soldiers

India’s Child Soldiers: Government defends officially designated terror groups’ record on the recruitment of child soldiers before the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child Asian Centre For Human Rights India’s Child Soldiers: Government defends officially designated terror groups’ record on the recruitment of child soldiers before the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child A shadow report to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict Asian Centre For Human Rights India’s Child Soldiers Published by: Asian Centre for Human Rights C-3/441-C, Janakpuri, New Delhi 110058 INDIA Tel/Fax: +91 11 25620583, 25503624 Website: www.achrweb.org Email: [email protected] First published March 2013 ©Asian Centre for Human Rights, 2013 No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the publisher. ISBN : 978-81-88987-31-3 Suggested contribution Rs. 295/- Acknowledgement: This report is being published as a part of the ACHR’s “National Campaign for Prevention of Violence Against Children in Conflict with the Law in India” - a project funded by the European Commission under the European Instrument for Human Rights and Democracy – the European Union’s programme that aims to promote and support human rights and democracy worldwide. The views expressed are of the Asian Centre for Human Rights, and not of the European Commission. Asian Centre for Human Rights would also like to thank Ms Gitika Talukdar of Guwahati, a photo journalist, for the permission to use the photographs of the child soldiers. -

M.A. /M.Sc. in Criminology & Police Studies Syllabus

SARDAR PATEL UNIVERSITY OF POLICE, SECURITY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE JODHPUR, RAJASTHAN, INDIA M.A. /M.Sc. in Criminology & Police Studies SYLLABUS From the Academic Year 2017 - 2018 Onwards 1 SARDAR PATEL UNIVERSITY OF POLICE, SECURITY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE, JODHPUR, RAJASTHAN, INDIA M.A. /M. Sc. in Criminology and Police Studies From the academic year 2017 - 2018 onwards Scheme, Regulations and Syllabus Title of the course M.A/M.Sc in Criminology and Police Studies Duration of the course Two Years under Semester Pattern. Eligibility Graduate in any discipline with minimum 55% marks. (5% relaxation for SC/ST/PH candidates) Total Credit Points: 105 Structure of the programme This Master’s programme will consist of: a. Compulsory Papers and Elective Papers; I Semester: (22 Credits) 4 Compulsory Papers, 1 Elective Paper & 1 Practical Paper II Semester: (27 Credits) 4 Compulsory Papers, 1 Elective Paper & 2 Practical Papers (1 of them elective), Winter Internship (to be commenced at the ending of I semester and finished at beginning of II Semester) III Semester: (32 Credits) 4 Compulsory Papers, 1 Elective Paper, 1 Practical Paper & Summer Internship (to be commenced at the ending of II semester and finished at beginning of III Semester) Theory Papers: Each theory paper comprises 4 Contact hours / week. 4 Contact Hours = 2 Lectures+ 1 Tutorial+ 1 Seminar 2 • Electives: Electives will be offered only if a minimum of 5 students opt for that paper. • Practical Paper : The Subject called ‘Practical Paper’ may include any of the/some of the following activities such as Institutional field visits(for practical) & debate on particular issues or article writing on particular issues related to the subject / subject related discussion on short-films/ field based case-study etc. -

The Indian Police Journal Vol

Vol. 63 No. 2-3 ISSN 0537-2429 April-September, 2016 The Indian Police Journal Vol. 63 • No. 2-3 • April-Septermber, 2016 BOARD OF REVIEWERS 1. Shri R.K. Raghavan, IPS(Retd.) 13. Prof. Ajay Kumar Jain Former Director, CBI B-1, Scholar Building, Management Development Institute, Mehrauli Road, 2. Shri. P.M. Nair Sukrali Chair Prof. TISS, Mumbai 14. Shri Balwinder Singh 3. Shri Vijay Raghawan Former Special Director, CBI Prof. TISS, Mumbai Former Secretary, CVC 4. Shri N. Ramachandran 15. Shri Nand Kumar Saravade President, Indian Police Foundation. CEO, Data Security Council of India New Delhi-110017 16. Shri M.L. Sharma 5. Prof. (Dr.) Arvind Verma Former Director, CBI Dept. of Criminal Justice, Indiana University, 17. Shri S. Balaji Bloomington, IN 47405 USA Former Spl. DG, NIA 6. Dr. Trinath Mishra, IPS(Retd.) 18. Prof. N. Bala Krishnan Ex. Director, CBI Hony. Professor Ex. DG, CRPF, Ex. DG, CISF Super Computer Education Research Centre, Indian Institute of Science, 7. Prof. V.S. Mani Bengaluru Former Prof. JNU 19. Dr. Lalji Singh 8. Shri Rakesh Jaruhar MD, Genome Foundation, Former Spl. DG, CRPF Hyderabad-500003 20. Shri R.C. Arora 9. Shri Salim Ali DG(Retd.) Former Director (R&D), Former Spl. Director, CBI BPR&D 10. Shri Sanjay Singh, IPS 21. Prof. Upneet Lalli IGP-I, CID, West Bengal Dy. Director, RICA, Chandigarh 11. Dr. K.P.C. Gandhi 22. Prof. (Retd.) B.K. Nagla Director of AP Forensic Science Labs Former Professor 12. Dr. J.R. Gaur, 23 Dr. A.K. Saxena Former Director, FSL, Shimla (H.P.) Former Prof. -

Action Taken Report on the Recommendations of 6Th National Conference of Women in Police Held from 26Th to 28Th February, 2014 at Guwahati, Assam

ACTION TAKEN REPORT ON THE RECOMMENDATIONS OF 6TH NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF WOMEN IN POLICE HELD FROM 26TH TO 28TH FEBRUARY, 2014 AT GUWAHATI, ASSAM. Sub Theme: 1:-Professionalism and Capacity Building States Name Status of Recommendations & Recommendation (i) Special capacity building for women considering the Punjab Every women police official recruited in Punjab Police is given limited exposure of women police officers to core police basic training on subjects like, Forensic Science, IT/Computers, functions in the past. Components: Investigation of Special Crime such as Domestic Violence, Sexual Forensics Assault, Crime Against Children and Human Trafficking at PPA, IT/Computers Phillaur. The training to the women police officials regarding Counselling collection of intelligence and other such related topics is being Investigation of special crimes- Domestic Violence , imparted at Intelligence Training School, Sector-22, Chandigarh. Sexual Assault, Juveniles, Human Trafficking Steps are being taken to ensure greater participation of women Intelligence collection. officers in in-service courses at PPA, Phillaur and District Training Schools established in each district. Assam A list of all Unarmed Branch Officers from the rank of Constable to Superintendent may be maintained in PHQ with their bio-data and areas of special training. A copy of the data may be furnished to Addl. DGP (CID), Assam and Addl. DGP (TAP), Assam for the purpose of nominating them for various training courses. UT Chandigarh The women police officials are being trained by holding various workshops regarding field work of Forensic, IT/Computer, Counseling, Investigations in Special Crime and Intelligence. Goa - Nagaland All the aforementioned components are extensively covered in all types of Training being conducted at Nagaland Police Training School, Nagaland, Chumukedima. -

Community Policing in Andhra Pradesh: a Case Study of Hyderabad Police

Community Policing in Andhra Pradesh: A Case Study of Hyderabad Police Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION By A. KUMARA SWAMY (Research Scholar) Under the Supervision of Dr. P. MOHAN RAO Associate Professor Railway Degree College Department of Public Administration Osmania University DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION University College of Arts and Social Sciences Osmania University, Hyderabad, Telangana-INDIA JANUARY – 2018 1 DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION University College of Arts and Social Sciences Osmania University, Hyderabad, Telangana-INDIA CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “Community Policing in Andhra Pradesh: A Case Study of Hyderabad Police”submitted by Mr. A.Kumara Swamy in fulfillment for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public Administration is an original work caused out by him under my supervision and guidance. The thesis or a part there of has not been submitted for the award of any other degree. (Signature of the Guide) Dr. P. Mohan Rao Associate Professor Railway Degree College Department of Public Administration Osmania University, Hyderabad. 2 DECLARATION This thesis entitled “Community Policing in Andhra Pradesh: A Case Study of Hyderabad Police” submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public Administration is entity original and has not been submitted before, either or parts or in full to any University for any research Degree. A. KUMARA SWAMY Research Scholar 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am thankful to a number of individuals and institution without whose help and cooperation, this doctoral study would not have been possible. -

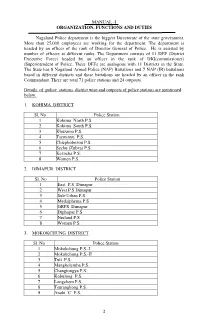

Organization, Functions and Duties

MANUAL -I ORGANIZATION, FUNCTIONS AND DUTIES Nagaland Police department is the biggest Directorate of the state government. More than 25,000 employees are working for the department. The department is headed by an officer of the rank of Director General of Police. He is assisted by number of officers at different ranks. The Department consists of 11 DEF (District Executive Force) headed by an officer in the rank of DIG(commissioner) /Superintendent of Police. These DEFs are analogous with 11 Districts in the State. The State has 8 Nagaland Armed Police (NAP) Battalions and 7 NAP (IR) battalions based in different districts and these battalions are headed by an officer in the rank Commandant. There are total 71 police stations and 24 outposts. Details of police stations district wise and outposts of police stations are mentioned below. 1. KOHIMA DISTRICT Sl. No Police Station 1 Kohima North P.S. 2 Kohima South P.S. 3 Khuzama P.S. 4 Tseminyu P.S. 5 Chiephobozou P.S. 6 Sechu (Zubza) P.S. 7 Kezocha P.S. 8 Women P.S. 2. DIMAPUR DISTRICT Sl. No Police Station 1 East P.S Dimapur 2 West P.S Dimapur 3 Sub-Urban P.S 4 Medziphema P.S 5 GRPS Dimapur 6 Diphupar P.S 7 Niuland P.S 8 Women P.S. 3. MOKOKCHUNG DISTRICT Sl. No Police Station 1 Mokokchung P.S.-I 2 Mokokchung P.S.-II 3 Tuli P.S. 4 Mangkolemba P.S. 5 Changtongya P.S. 6 Kobulong P.S. 7 Longchem P.S. 8 Tsurangkong P.S. -

ANTI RAGGING POLICY (For Prohibition, Prevention & Punishment)

ANTI RAGGING POLICY (For Prohibition, Prevention & Punishment) SAY ‘NO’ TO RAGGING RAGGING STUDENT BROCHURE Ragging - A Violation of Human Rights Ragging is strictly prohibited on campus & off campus Vidya Jyothi Institute of Technology (AUTONOMOUS) (Accredited by NAAC, Approved by AICTE New Delhi & Permanently Affiliated to JNTUH) Aziznagar Gate, C.B. Post, Hyderabad-500 075) AWARENESS OF RAGGING As per the orders of the Hon'ble Supreme Court of India, UGC Regulations and the Andhra Pradesh Prohibition of Ragging Act 1997 as adopted by the State Govt. of Telangana. Ragging is considered as a sadistic thrill, and it is a violation of Human Rights. INSTRUCTIONS TO FRESHERS 1. You do not have to submit to ragging in any form. 2. You do not have to compromise with your dignity and self-respect. 3. You can report incidents of ragging to the authorities concerned. 4. You can contact any member of the Anti Ragging Squad / Anti Ragging Committee of the College, or the Principal. 5. The college is obliged to permit the use of communication facilities (Landline and Mobile phones) for seeking help. 6. If you are not satisfied with the enquiry conducted by the College, you can lodge a First Information Report (FIR) with the local Police, and can complain with the civil authorities also. 7. The college is in any case required to file FIR if your parents or you are not satisfied with the action taken against those who 'ragged' you. 8. Your complaint can be oral or written, and would be treated by the authorities in strict confidence. -

Joining Instructions Reg 12 Th All India Police Badminton Championship-2019 at Central Academy for Police Training (Capt), Bhopal from 03 to 09 February, 2020

Ministry of Home Affairs Bureau of Police Research & Development Central Academy for Police Training PO – Kokta, Bhopal (MP) – 462 022 Tele: 0755-2706000 No.38/Sports/CAPT/Bhopal/2019/ Dated, the __ December, 2019 1. The Director General, BSF, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110003 2. The Director General, CISF, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110003 3. The Director General, CRPF, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi – 110003 4. The Director General, ITBP, Block 2, CGO Complex, New Delhi-110003 5. The Director General, RPF, Rail Bhawan, New Delhi 6. The Director General, BPR&D, NH-8, Mahipalpur Extnesion, Mahipalpur, New Delhi-110037 7. The Director General, NSG, Mehram Nagar, Near Domestic Airport, Palam, New Delhi-110037 8. The Director General, SSB, East Block-5, R.K. Puram, New Delhi-110066 9. The Director General of, Assam Rifles, East Khast Hills, Shillong, Meghalaya 10. The Director, CBI, Plot No. 5B, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi- 110003 11. The Director, SVP, NPA, Shivarampalli, Hyderabad, A.P.-500052 12. The Director General, Administrative Block, SPG Complex, 9 Lok Kalyan Marg, New Delhi-110011 13. The Director, Intelligence Bureau, Hall No.02, Ground Floor, IBCTS Building, Gate No.4, 35 Sardar Patel Marg, New Delhi-110021 14. The Director, CBI, Plot No.5B, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi- 110003 15. The Director General of Police, Andhra Pradesh, 3rd Floor, Old DGP Office, Police Headquarters, Hyderabad (AP)-500004 16. The Director General of Police, Police Headquarter (PHQ), Chandranagar, Arunachal Pradesh-791111 17. The Director General of Police, Police Headquarter, Uluvari, Guwahati, Assam-781007 18. -

Study Among the Victims of Child Sexual Abuse in the City of Chennai

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN (P): 2347-4564; ISSN (E): 2321-8878 Vol. 7, Issue 5, May 2019, 43-56 © Impact Journals A STUDY AMONG THE VICTIMS OF CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE IN THE CITY OF CHENNAI S. Latha 1 & Lekha Sri. P 2 1Assistant Professor, Department of Criminology, University of Madras, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India 2Research Scholar, Criminology and Criminal Justice Sciences, Department of Criminology, University of Madras, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India Received: 09 Apr 2019 Accepted: 27 Apr 2019 Published: 09 May 2019 ABSTRACT The problem of child abuse is age-old but the dimensions are new. Every day a new way of harassing children takes place in every part of the world. Since it is a continuous problem we can’t leave the same unstudied and un- researched. In the recent past, many incidents of child abuse are being reported in media. This has created a kind of fear among the public. These recent incidences have raised many questions especially on the causes of the child abuse and protection of children. The present study aimed to conduct empirical research on the reported cases of child sexual abuse registered under POCSO Act in the city of Chennai in the year 2018. KEYWORDS: Child Abuse, Child Rape. Sexual Harassment, Victimization INTRODUCTION A child is a person who is going to carry on what you have started. He is going to be where you are sitting and when you are gone, Attend to those things you think are important “ Abraham Lincoln “Children are the treasure of future and assets of the Nation” Mahatma Gandhi Children are the pillars of any country. -

Functions, Roles and Duties of Police in General

Chapter 1 Functions, Roles and Duties of Police in General Introduction 1. Police are one of the most ubiquitous organisations of the society. The policemen, therefore, happen to be the most visible representatives of the government. In an hour of need, danger, crisis and difficulty, when a citizen does not know, what to do and whom to approach, the police station and a policeman happen to be the most appropriate and approachable unit and person for him. The police are expected to be the most accessible, interactive and dynamic organisation of any society. Their roles, functions and duties in the society are natural to be varied, and multifarious on the one hand; and complicated, knotty and complex on the other. Broadly speaking the twin roles, which the police are expected to play in a society are maintenance of law and maintenance of order. However, the ramifications of these two duties are numerous, which result in making a large inventory of duties, functions, powers, roles and responsibilities of the police organisation. Role, Functions and Duties of the Police in General 2. The role and functions of the police in general are: (a) to uphold and enforce the law impartially, and to protect life, liberty, property, human rights, and dignity of the members of the public; (b) to promote and preserve public order; (c) to protect internal security, to prevent and control terrorist activities, breaches of communal harmony, militant activities and other situations affecting Internal Security; (d) to protect public properties including roads,