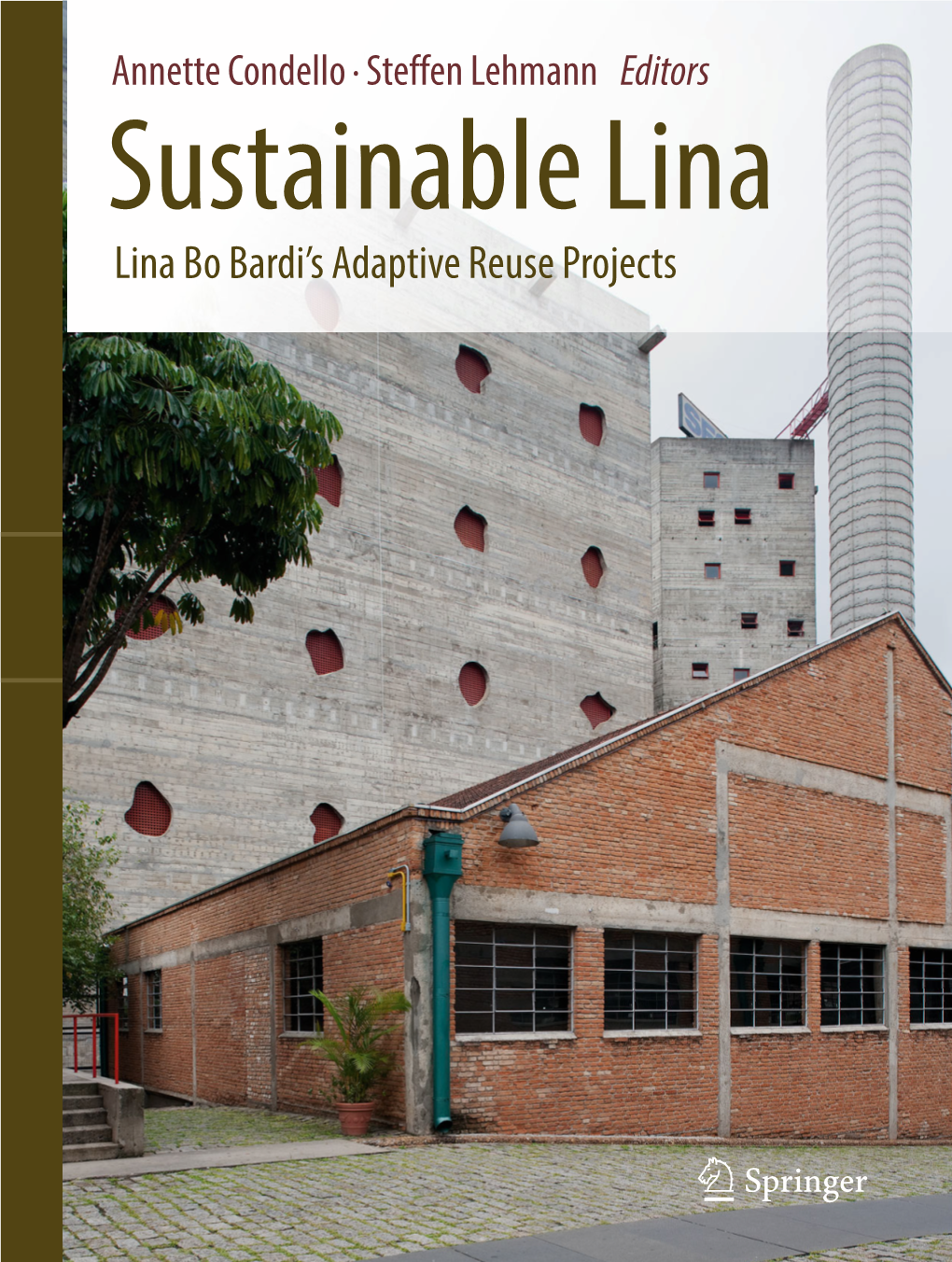

Lina Bo Bardi's Adaptive Reuse Projects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HERITAGE UNDER SIEGE in BRAZIL the Bolsonaro Government Announced the Auction Sale of the Palácio Capanema in Rio, a Modern

HERITAGE UNDER SIEGE IN BRAZIL the Bolsonaro Government announced the auction sale of the Palácio Capanema in Rio, a modern architecture icon that was formerly the Ministry of Education building FIRST NAME AND FAMILY NAME / COUNTRY TITLE, ORGANIZATION / CITY HUBERT-JAN HENKET, NL Honorary President of DOCOMOMO international ANA TOSTÕES, PORTUGAL Chair, DOCOMOMO International RENATO DA GAMA-ROSA COSTA, BRASIL Chair, DOCOMOMO Brasil LOUISE NOELLE GRAS, MEXICO Chair, DOCOMOMO Mexico HORACIO TORRENT, CHILE Chair, DOCOMOMO Chile THEODORE PRUDON, USA Chair, DOCOMOMO US LIZ WAYTKUS, USA Executive Director, DOCOMOMO US, New York IVONNE MARIA MARCIAL VEGA, PUERTO RICO Chair, DOCOMOMO Puerto Rico JÖRG HASPEL, GERMANY Chair, DOCOMOMO Germany PETR VORLIK / CZECH REPUBLIC Chair, DOCOMOMO Czech Republic PHILIP BOYLE / UK Chair, DOCOMOMO UK OLA ODUKU/ GHANA Chair, DOCOMOMO Ghana SUSANA LANDROVE, SPAIN Director, Fundación DOCOMOMO Ibérico, Barcelona IVONNE MARIA MARCIAL VEGA, PUERTO RICO Chair, DOCOMOMO Puerto Rico CAROLINA QUIROGA, ARGENTINA Chair, DOCOMOMO Argentina RUI LEAO / MACAU Chair, DOCOMOMO Macau UTA POTTGIESSER / GERMANY Vice-Chair, DOCOMOMO Germany / Berlin - Chair elect, DOCOMOMO International / Delft ANTOINE PICON, FRANCE Chairman, Fondation Le Corbusier PHYLLIS LAMBERT. CANADA Founding Director Imerita. Canadian Centre for Architecture. Montreal MARIA ELISA COSTA, BRASIL Presidente, CASA DE LUCIO COSTA/ Ex Presidente, IPHAN/ Rio de Janeiro JULIETA SOBRAL Diretora Executiva, CASA DE LUCIO COSTA, Rio de Janeiro ANA LUCIA NIEMEYER/ BRAZIL -

Paulonascimentoverano.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO Escola de Comunicações e Artes Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência da Informação PAULO NASCIMENTO VERANO POR UMA POLÍTICA CULTURAL QUE DIALOGUE COM A CIDADE O caso do encontro entre o MASP e o graffiti (2008-2011) São Paulo 2013 PAULO NASCIMENTO VERANO POR UMA POLÍTICA CULTURAL QUE DIALOGUE COM A CIDADE O caso do encontro entre o MASP e o graffiti (2008-2011) Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência da Informação da Escola de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo, como requisito para obtenção do título de mestre em Ciência da Informação. Orientadora: Profª Drª Lúcia Maciel Barbosa de Oliveira Área de concentração: Informação e Cultura São Paulo 2013 Autorizo a reprodução e divulgação total ou parcial deste trabalho, por qualquer meio convencional ou eletrônico, para fins de estudo e pesquisa desde que citada a fonte. PAULO NASCIMENTO VERANO POR UMA POLÍTICA CULTURAL QUE DIALOGUE COM A CIDADE O caso do encontro entre o MASP e o graffiti (2008-2011) Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência da Informação da Escola de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo, como requisito para obtenção do título de mestre em Ciência da Informação. BANCA EXAMINADORA _____________________________________________________ a a Prof Dr Lúcia Maciel Barbosa de Oliveira (orientadora) Universidade de São Paulo _____________________________________________________ Universidade de São Paulo _____________________________________________________ Universidade de São Paulo CLARICE, CLARIDADE, CLARICIDADE. AGRADECIMENTOS Sou profundamente grato à Profa Dra Lúcia Maciel Barbosa de Oliveira pela oportunidade dada para a realização deste estudo. Sua orientação sempre presente e amiga, o diálogo aberto, as aulas ministradas, as indicações bibliográficas, a leitura atenta e exigente durante todas as fases desta dissertação, dos esboços iniciais à versão final. -

7. Another Museum (Display and Desire)

7. Another Museum (Display and Desire) The search for the real, in particular for real relations, and specifically the search for real relations between objects and people, takes on the form of utopia. Whether it be works of art (objects that are primarily non-relational), or products of the disenfranchised (objects of desperate survival), or ill-begotten treasures (objects collected in order to make the past present to the undeserving, taking away from others the possibility to figure the future), author Roger M Buergel, interpreting the displays of architect Lina Bo Bardi in the light of migration, and critic Pablo Lafuente, reading a work by artist Lukas Duwenhögger, demonstrate that things will, given the right circumstances, elicit subjectivity in spectatorship. agency, ambivalence, analysis: approaching the museum with migration in mind — 177 The Migration of a Few Things We Call − But Don’t Need to Call − Artworks → roger m buergel → i In 1946, 32-year-old Italian architect Lina Bo Bardi migrated to Brazil. She was accompanying her husband, Pietro Maria Bardi, who was a self- taught intellectual, gallerist and impresario of Italy’s architectural avant garde during Mussolini’s reign. Bardi had been entrusted by Assis de Chateaubriand, a Brazilian media tycoon and politician, with creating an art institution of international standing in São Paulo. Te São Paulo Art Museum (MASP) had yet to fnd an appropriate building to house its magnifcent collection of sculptures and paintings by artists ranging from Raphael to Manet. Te recent acquisitions were chosen by Bardi himself on an extended shopping spree funded by Assis Chateaubriand, who had taken out a loan from Chase Manhattan Bank in an impoverished, chaotic post-war Europe. -

Leilão De Arte

JUCESP Nº 336 LEILÃO DE ARTE DIAS 18 E 19 DE MARÇO (TERÇA E QUARTA-FEIRA) ÀS 21:00 HORAS ATENÇÃO PARA OS ENDEREÇOS PRIMEIRA NOITE - LOTES 1 A 138 DIA 18 - LEOPOLLDO JARDINS RUA PRUDENTE CORREIA, 432 - JARDIM EUROPA (ESQUINA COM A AV. FARIA LIMA, EM FRENTE AO SHOPPING IGUATEMI) SEGUNDA NOITE - LOTES 139 A 265 DIA 19 - JAMES LISBOA LEILOEIRO OFICIAL RUA DR. MELO ALVES, 397 - JARDINS No dia do pregão as obras serão apresentadas somente por projeção, a apreciação física das mesmas poderá ser feita somente durante a exposição. Apoio: Textos: Fernando AQ Mota LEILÃO DE ARTE ÍNDICE Adolphe D’ Hastrel ........................................ 226 Estevan De Souza ........................................ 188 Nuno Ramos .................................................. 153 DIAS 18 E 19 DE MARÇO Adriano Lemos .............................................. 265 Fábio Miguez ........................................... 36, 162 Omar Rayo ......................................................... 1 (TERÇA E QUARTA-FEIRA) Alberto Balestro ........................................... 257 Fayga Ostrower ............................................ 245 Orlando Teruz ............................... 130, 194, 195 Alberto Lume ................................................ 260 Fernando Lemos .............................................. 31 OsGemeos ........................................................ 42 Aldemir Martins ...... 62, 117, 119, 132, 133, 221 Fernando Odriozola ............................ 142, 208 Otto Stupakoff ............................................. -

Ideias De Brasil Nas Representações De Um Crítico E De Artistas E Arquitetos Italianos Depois Da Segunda Guerra Mundial Anais Do Museu Paulista, Vol

Anais do Museu Paulista ISSN: 0101-4714 [email protected] Universidade de São Paulo Brasil Coelho Sanches Corato, Aline Além do “silêncio de um oceano”. Ideias de Brasil nas representações de um crítico e de artistas e arquitetos italianos depois da Segunda Guerra Mundial Anais do Museu Paulista, vol. 24, núm. 2, mayo-agosto, 2016, pp. 187-215 Universidade de São Paulo São Paulo, Brasil Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=27348477007 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Mais artigos Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina, Caribe , Espanha e Portugal Home da revista no Redalyc Projeto acadêmico sem fins lucrativos desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa Acesso Aberto http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1982-02672016v24n0206 Além do “silêncio de um oceano”. Ideias de Brasil nas representações de um crítico e de artistas e arquitetos italianos depois da Segunda Guerra Mundial1 Aline Coelho Sanches Corato2 1. Este artigo é uma síntese do primeiro capítulo da mi- nha tese de doutorado de- RESUMO: Este artigo investiga as ideias de Brasil formuladas em uma seleção de cartas, ar- fendida em março de 2012. O trabalho foi desenvolvido tigos, fotografias, desenhos, pinturas e mostras, entre 1947 e 1963 pelos arquitetos Lina Bo com bolsa do Politecnico di Bardi e Giancarlo Palanti, pelos artistas Roberto Sambonet e Bramante Buffoni, e pelo crítico Milano, sob orientação do prof. Daniele Vitale (Politec- de arte Pietro Maria Bardi – italianos imigrados no país após a Segunda Guerra Mundial. O nico di Milano), co-orientação novo país é visto como o lugar onde parece possível a realização das promessas da arte e da do prof. -

MAM Leva Obras De Seu Acervo Para As Ruas Da Cidade De São Paulo Em Painéis Urbanos E Projeções

MAM leva obras de seu acervo para as ruas da cidade de São Paulo em painéis urbanos e projeções Ação propõe expandir as fronteiras do Museu para além do Parque Ibirapuera, para toda a cidade, e busca atingir públicos diversos. Obras de artistas emblemáticos da arte brasileira, de Tarsila do Amaral a Regina Silveira, serão espalhadas pela capital paulista Incentivar e difundir a arte moderna e contemporânea brasileira, e torná-la acessível ao maior número possível de pessoas. Este é um dos pilares que regem o Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo e é também o cerne da ação inédita que a instituição promove nas ruas da cidade. O MAM expande seu espaço físico e, até 31 de agosto, apresenta obras de seu acervo em painéis de pontos de ônibus e projeções de escala monumental em edifícios do centro de São Paulo. A ação MAM na Cidade reforça a missão do Museu em democratizar o acesso à arte e surge, também, como resposta às novas dinâmicas sociais impostas pela pandemia. “A democratização à arte faz parte da essência do MAM, e é uma missão que desenvolvemos por meio de programas expositivos e iniciativas diversas, desde iniciativas pioneiras do Educativo que dialogam com o público diverso dentro e fora do Parque Ibirapuera, até ações digitais que ampliam o acesso ao acervo, trazem mostras online e conteúdo cultural. Com o MAM na Cidade, queremos promover uma nova forma de experienciar o Museu. É um presente que oferecemos à São Paulo”, diz Mariana Guarini Berenguer, presidente do MAM São Paulo. Ao longo de duas semanas, MAM na Cidade apresentará imagens de obras de 16 artistas brasileiros espalhadas pela capital paulista em 140 painéis em pontos de ônibus. -

Ivj IX *>Ül V. ARTES PLÁSTICAS» PARTICIPA

UNIVERSIDADE DE SXO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS Cw- iVJ IX *>ül v. ARTES PLÁSTICAS» PARTICIPAÇÃO E DISTINÇÃO BRASIL ANOS 60/70 Autora: Maria Amélia Bulhões Garcia S3o Paulo, 1990 UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS ARTES PLÁSTICAS» PARTICIPAÇÃO E DISTINÇÃO BRASIL ANOS 60/70 Autora: Maria Amélia Bulhões Garcia Orientador: Prof. Dr. Carlos Roberto Nogueira Tese de Doutorado apresentada ao curso de Pós- Grasduação em História Social da Universidade de São Paulo, para obtenção do Título de Doutor. São Paulo, 1990 III Dedicatória A Néstor Garcia Canclini que me auxilou a chegar até aqui e a todos a quem este trabalho possa ser útil em uma caminhada que é de muitos. AGRADECIMENTOS Foram muitas as descobertas ao longo desta trajetória. Como agradecer a todos se a grande descoberta foi a de quanto * coletivo qualquer tipo de trabalho. Alguns estão aqui referenciados, talvez outros tenham sido omitidos. Não deveria agradecer a todos os estudados? Que fazer? Agradecimentos oficiais e afetivos aqui estãos - Ao Departamento de História da UFRGS, pela liberação dos encargos docentes, mas antes de mais nada pelos desafios colocados. Ao CNPq e FUNARTE pelo apoio à pesquisa possibilitando a sua realização. À CAPES pela bolsa que custeou meus estudos e pela viagem ao México, fonte de inesgotáveis conhecimentos. - À PROPESP, pelo apoio permanente. Ao Prof. Dr. Carlos Guilherme Mota, que acreditou neste projeto quando ele era ainda uma semente. V - Ao Prof. Dr. Carlos Roberto Nogueira, um orientador amigo- - À Rosana e Meg, companheiras na pesquisa e nos questionamentos. - À Blanca e Mônica, as amigas de todos os momentos- - À Loiva, por seu estímulo e exemplo. -

Lina Bo Bardi 100 Years Young

Gardenhouse: Hertl.Architekten converted the ruin of an old farmhouse in Austria using the concept of the house-in-house Since 1928 Italiano Sign up / Log in Search Domus... Like You, Bart Lootsma and 441,360 others like this. Architecture / Design / Art / Products / Domus Archive / Shop Contents News / Interviews / Op-ed / Photo-essays / Specials / Reviews / Video / From the archive / Competitions Magazine Current issue / Local editions Network Your profile / RSS / facebook / twitter / instagram / pinterest / LOVES Lina Bo Bardi 100 years young Following on from the current exhibitions and those recently ended, the catalogues, the video, the talks that help refocus attention on Lina who was an ingenious architect, a designer of fantastic things and animals, a thinker, a graphic artist and a sophisticated set designer. Architecture / Giacomo Pirazzoli Author Sections Network Giacomo Pirazzoli Architecture Like on Facebook Share on Twitter Published Keywords 5 December 2014 Arper, Gio Ponti, Lina Bo Bardi, Lina Bo Bardi Pin to Pinterest 100, Lina Bo Bardi Together, MASP, MAXXI, Location Pietro Maria Bardi, Precise Poetry, SESC San Paolo Pompeia These thoughts on the 100th anniversary of Lina Bo Bardi’s birth in Rome on 5 December 1914 is a parti-pris on the LinaProject.com collaboration platform – a project open to scholars, connoisseurs and admirers of “Dona Lina”, which I am coordinating for the Department of Architecture of Florence University. In apertura: Lina Bo Bardi, 1960. Photo © Arquivo ILBPMB. Qui sopra: Casa de Vidro, São Paulo, with Lina Bo Bardi, 1949-1951. Photo Francisco Albuquerque, 1951, © Arquivo ILBPMB A sense of scientific focus and attentiveness emerges from a recent visit to the orderly shelves of the “Dona Lina” archives at the Instituto Lina Bo e Pietro Maria Bardi in Saõ Paulo – in the famous Glass House built by the architect as a home for herself and her husband. -

Brazil's Best-Kept Secret

BBC - Culture - Lina Bo Bardi: Brazil’s best-kept secret http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20140611-brazils-best-kept-secret BRAZIL BEYOND FOOTBALL (HTTP://WWW.BBC.COM/CULTURE/COLUMNS/BRAZIL-BEYOND-FOOTBALL) | 11 June 2014 Jason Farago Art (http://www.bbc.com/culture/sections/art) Architecture (http://www.bbc.com/culture/tags/architecture) Design (http://www.bbc.com/culture/tags/design) Exhibition (http://www.bbc.com/culture/tags/exhibition) Museums (http://www.bbc.com/culture/tags/museum) Politics (http://www.bbc.com/culture/tags/politics) The Museu de Arte de São Paulo (SambaPhoto/Ed Viggiani/Getty) The Italian-born architect’s radical approach to the design of people-friendly buildings in Brazil should receive greater recognition, Jason Farago argues. Like no other country of its size, Brazil has projected its character to the world through modern architecture – the government buildings and housing projects of Brasília, the skyscrapers along São Paulo’s broad Avenida Paulista, the pleasure palaces of Rio’s Sambódromo and Maracanã stadium. We think we know the look of Brazil. For all the beauty of Copacabana and the Amazon, Brazil in our imaginations is a built environment, one where International Style modernism was souped up with plunging curves, organic detailing, and lush greenery. One woman in particular can help us expand our view not just of Brazil but of modern architecture at large. Lina Bo Bardi, an Italian-born architect with an uncommon commitment to building for society’s needs, was just getting her practice started when Lúcio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer began to adapt international modernism for local purposes. -

Gendering Architecture, Architecting Gender Introduction

GENDERING ARCHITECTURE, ARCHITECTING GENDER INTRODUCTION The Women in Architecture Student Organization (WIASO) presents: Gendering Architecture, Architecting Gender, a celebration of female architects throughout history as well as contemporary female architects often neglected or erased in mainstream media and architectural curricula. By showcasing works by female architects, WIASO hopes to counteract the dominant narrative of the architect as a male subject. This exhibition works to rewrite architectural history by acknowledging the contributions of female architects who have been dismissed, belitted, or denied credit for their work. By looking at architectural movements from a critical, feminist perspective, one is able to recenter history around marginalized identities and redefine what it means to be an architect. The exhibition is a glimpse at a shared history among female architects at the University of Minnesota, one that architecture students are learning about and contributing to daily. Women’s School of Planning and Architecture, 1975 EXHIBITION CREDITS DESIGN & CURATION Support for this exhibition and programs provided by the Goldstein Museum of Design, the College of Design, and generous individuals. In addition, GMD programming is made possible by the voters of Minnesota Neva Hubbert UMN Architecture Student through a Minnesota State Arts Board Operating Support grant, thanks to Dana Saari UMN Architecture Student the legislative appropriation from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund. The Mary Begley UMN Architecture Student University of Minnesota is an equal opportunity educator and employer. To request disability accomodations or to receive this information in Erin Kindell UMN Architecture Student alternative formats, please contact GMD at 612-624-7434. Brittany Pool UMN Architecture Student EDITING & ASSISTANCE Daniela Sandler UMN Architecture Faculty Goldstein Museum of Design Ashleigh Grizzell UMN Architecture Student Gallery 241, McNeal Hall 1985 Buford Avenue St. -

Bowl: a Chair for Freedom

Bowl: A Chair for Freedom By Adélia Borges Six decades ago, chairs would rigidly dictate the way people should sit on them. Users had just one option: to sit up straight. The 1951 Bowl Chair arrived to shake up this scene. Man no longer obeyed the object; now the object would obey man, according to their movements and desires. Far from limiting or constraining users, it would free them. Freedom is a key word in the ideas and trajectory of the chair’s creator, Lina Bo Bardi, and an everyday practice in her plural activities. In all the dimensions of her work, more than technique or aesthetics, she was interested in serving human beings. ‘True architecture is a total process, embracing human beings’ economic, political and social relationships,’ Lina wrote. ‘Surely beauty, a beautiful form, is capable of consoling man. Poetry in form is vital. However, without architecture’s social sense, all of this gets lost. Man is the ultimate objective of architecture.’ The Bowl Chair illustrates this enunciation perfectly. The poetry in its essential form comes to the forefront at first sight. It can be summed up as a shell deposited on a tubular frame. These two pieces are loose, superimposed without any means of fixation. ‘What is new in this piece of furniture, what is absolutely new, is the fact that the chair can achieve movement from all sides, with no mechanic means whatsoever, only due to its spherical form. There are no other pieces of furniture of this kind,’ Lina wrote about her Bowl Chair. Innovation was evident, so much so the chair was featured in a cover story in the renowned American magazine Interiors in November 1953, sixty years ago – a notable feat, considering Brazil was, at that time, regarded as a peripheral country in the design arena, with its creations usually destined to invisibility, the opposite of what was happening in centers of power such as New York, London, or Milan. -

Considerações Sobre a Formação E Profissionalização De Educadores De Museus E Exposições De Arte

UNESP UIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL PAULISTA “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” Instituto de Artes Programa De Pós-Graduação Em Artes Mestrado O MEDIADOR CULTURAL. Considerações sobre a formação e profissionalização de educadores de museus e exposições de Arte Valéria Peixoto de Alencar São Paulo 2008 UNESP UIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL PAULISTA “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” Instituto de Artes Programa De Pós-Graduação Em Artes Mestrado O MEDIADOR CULTURAL. Considerações sobre a formação e profissionalização de educadores de museus e exposições de Arte Valéria Peixoto de Alencar Dissertação submetida à UNESP como requisito parcial exigido pelo Programa de Pós-graduação em Artes, área de concentração em Artes Visuais, linha de pesquisa: Ensino e Aprendizagem da Arte, sob a orientação da professora Dra. Rejane Galvão Coutinho, para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Artes. São Paulo 2008 Ficha catalográfica preparada pelo Serviço de Biblioteca e Documentação do Instituto de Artes da UNESP Alencar, Valéria Peixoto de A368m O mediador cultural : considerações sobre a formação e profissionalização de educadores de museus e exposições de arte / Valéria Peixoto de Alencar. - São Paulo : [s.n.], 2008. viii, 97 f. Bibliografia Orientador: Profa. Dra. Rejane Galvão Coutinho Dissertação (Mestrado em Artes) - Universidade Estadual Paulista, Instituto de Artes. 1. Educação – Museus. 2. Arte educação – Mediação cultural. 3. Arte – Estudo e ensino. 4. Formação profissional. I. Coutinho, Rejane Galvão. II. Universidade Estadual Paulista, Instituto de Artes. III. Título. CDD - 707 CDU – 7.07 Dedico À memória de meus pais, que sempre se dedicaram a mim. Minha mãe que me levou aos meus primeiros contatos com a Arte e meu pai que subsidiava estes encontros.