Dissertation (1.448Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

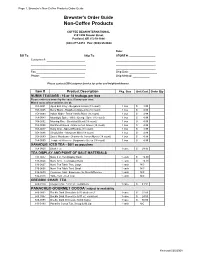

Non-Coffee Products Order Guide

Page 1, Brewster's Non-Coffee Products Order Guide Brewster's Order Guide Non-Coffee Products COFFEE BEAN INTERNATIONAL 2181 NW Nicolai Street Portland, OR 97210-1884 (800) 877-0474 Fax: (503)225-9604 Date: _________________ Bill To: Ship To: STORE #: _________________ Customer #: _________________________ __________________________ ____________________________________ __________________________ ____________________________________ __________________________ Fax:________________________________ Ship Date: __________________ Phone: _____________________________ Ship Method: ___________ Please contact CBI Customer Service for order and freight minimums. Item # Product Description Pkg. Size Unit Cost Order Qty NUMI® TEABAGS - 16 or 18 teabags per box Please order tea boxes by the case; 6 boxes per case. Mixed cases of tea varieties are ok. 358-0091 Aged Earl Grey - Bergamot Assam (18 count) 1 box $ 4.99 358-0085 Berry Black - Raspberry Darjeeling (16 count) 1 box $ 4.99 358-0093 Indian Night - Decaf Vanilla Black (16 count) 1 box $ 4.99 358-0083 Moonlight Spice - White Orange Spice (16 count) 1 box $ 4.99 358-0092 Morning Rise - Breakfast Blend (18 count) 1 box $ 4.99 358-0084 Rainforest Green - Mate Lemon Green (18 count) 1 box $ 4.99 358-0087 Ruby Chai - Spiced Rooibos (18 count) 1 box $ 4.99 358-0086 Simply Mint - Moroccan Mint (18 count) 1 box $ 4.99 358-0089 Sweet Meadows - Chamomile Lemon Myrtle (18 count) 1 box $ 4.99 358-0090 Temple of Heaven - Gunpowder Green (18 count) 1 box $ 4.99 XANADU® ICED TEA - 50/1 oz pouches 358-0060 Black Tea 1 case $ 29.95 TEA DISPLAY AND POINT OF SALE MATERIALS 513-0017 Numi 8 ct. Tea Display Rack 1 each $ 12.00 513-0024 Numi 12 ct. -

Country Coffee Profile Italy Icc-120-6 1

INTERNATIONAL COFFEE ORGANIZATION COUNTRY COFFEE PROFILE ITALY ICC-120-6 1 COUNTRY COFFEE PROFILE ITALY ICO Coffee Profile Italy 2 ICC-120-6 CONTENTS Preface .................................................................................................................................... 3 Foreword ................................................................................................................................. 4 1. Background ................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Geographical setting ....................................................................................... 5 1.2 Economic setting in Italy .................................................................................. 6 1.3 History of coffee in Italy .................................................................................. 6 2. Coffee imports from 2000 to 2016 ............................................................................. 8 2.1 Volume of imports .......................................................................................... 8 2.2 Value and unit value of imports ..................................................................... 14 2.3 Italian Customs – Import of green coffee ...................................................... 15 3. Re-exports from 2000 to 2016 ................................................................................... 16 3.1 Total volume of coffee re-exports by type and form ................................... -

Unesp UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL PAULISTA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO CM O) CO 00 O O O EM GEOGRAFIA MARCELA BARONE CAFÉS ESPECIAIS

unesp UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL PAULISTA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CM COO) O00 O GEOGRAFIA MARCELA BARONE CAFÉS ESPECIAIS E SALTO DE ESCALA: ANÁLISE DO CIRCUITO ESPACIAL PRODUTIVO E DOS CÍRCULOS DE COOPERAÇÃO DOS CAFÉS ESPECIAIS NO SUL DE MINAS GERAIS INSTITUTO DE GEOCIÊNCIAS E CIÊNCIAS EXATAS RIO CLARO 2017 ERRATA Barone, Marcela. Cafés especiais e salto de escala: análise do circuito espacial produtivo e dos círculos de cooperação dos cafés especiais do Sul de Minas Gerais. í Dls rtaçao Filho,f it. - Rio Claro,^ 2017. (Mestrado). Universidade Estadual Paulista Mio de Mesquita Folha Linha Onde se lê Leia-se 04 15 Aproveito para agradecer à Aproveito para agradecer Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa Fundação de Amparo do Estado de São Paulo pelo Pesquisa do Estado de São financiamento que possibilitou a Paulo (FAPESP) pelo realização desta pesquisa. financiamento que possibilitou a realização desta pesquisa, a partir dos processos n0 2014/09376-6 e 2015/01952-0. UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL PAULISTA "Júlio de Mesquita Filho" Instituto de Geociências e Ciências Exatas Câmpus de Rio Claro MARCELA BARONE CAFÉS ESPECIAIS E SALTO DE ESCALA: ANÁLISE DO CIRCUITO ESPACIAL PRODUTIVO E DOS CÍRCULOS DE COOPERAÇÃO DOS CAFÉS ESPECIAIS NO SUL DE MINAS GERAIS ísBBibliotecaib Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Instituto de Geociências e Ciências Exatas do Câmpus de Rio Claro, da Universidade Estadual Paulista "Júlio de Mesquita Filho", como parte dos requisitos para obtenção do título de Mestre em Geografia. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Samuel Frederico Rio Claro - SP 2017 ^ l 4 ( ^ T-8392 Tombo i ^«.c z?>W2 633.73 Barone, Marcela B265c Cafés especiais e salto de escala ; análise do circuito espacial produtivo e dos círculos de cooperação dos cafés especiais do Sul de Minas Gerais / Marcela Barone - Rio Claro, 2017 215 f. -

Coffee the Beverage of Commerce

Bar & Grille Coffee – the Beverage of Commerce The Beverage of Commerce Text & Photos by: Frank Barnett Fall 2010 Vol. 1 No. 4 Bar & Grille Coffee – the Beverage of Commerce y first real encounter with the mysterious, murky brew that so awakens the senses, giving me the necessary focus to make it through my days productively surprisingly Mdidn’t occur in the States. Once, a cup of coffee was just that to me, “a cup of joe”, an appellation that was given to the drink, according to coffee lovers, because of one Josephus Daniels. When he was appointed Secretary of the U.S. Navy by President Wilson in 1913, Daniels promptly abolished the officer’s wine mess and decreed that the strongest drink allowed aboard na- vel vessels, hence forth, would be coffee. The switch for me from just a cup of commodity coffee to a high culinary artform occurred almost two decades ago when coffee became transformed, at least in my impressionable mind, to a beverage ritual that often includes the accompaniment of a smooth, creamy cheese brioche, a delicate, flakey croissant or an Italian biscotti, its end dipped in chocolate. And, oh, how chocolate does compliment almost any form of coffee drink. There is, in fact, a strong chocolate connection between coffee and the confection that has been around since 1100 BC and was known by the Aztecs. Today, in both Europe and the US in better coffeehouses, the barista often assures that chocolate is made an integral part of the coffee experience by placing a Right: In addition to the pleasures of aroma and taste, latte art provides a treat for the visual senses as well. -

MT Febbraio 2017

FEBBRAIO 2017 IN QUESTO NUMERO 2 EDITORIALE La Colombia pronta alla ripresa 4 PANORAMA ITALIANO Starbucks a Milano nell’estate 2018 8 BORSE Dai massimi, ai minimi 12 NEWS & ATTUALITÀ Capucas Coffee Academy in Honduras Spedizione in A.P. -45% D.L. 353/2003 (conv. in L. 27/02/2004 n°46) art. 1, comma 2/DCB “TS” - N. 92 - Febbraio 2017 Febbraio - N. 92 2/DCB “TS” comma in L. 27/02/2004 n°46)art. 1, -45% D.L. 353/2003 (conv. in A.P. Spedizione POSTE ITALIANE S.p.A. - S.p.A. POSTE ITALIANE Thai Break: il gusto che ami, Coffee & Ginseng Drink rotondo 50 CAPSULE FAP. e appagante | SFUSO Thai Break è un prodotto | Tel. +39 0543 090113 www.foodrinks.it MONODOSE Febbraio 2017 Editoriale La Colombia pronta alla ripresa La produzione potrebbe tornare a 10 milioni di sacchi Il nuovo anno potrebbe essere finalmente, per il settore colombiano del caffè, l’anno della ripresa. Depongono a favore di questa tesi, le cifre diffuse dalla Federazione Nazionale dei Produttori Fedecafé, che evidenziano un consistente incremento produttivo +54% rispetto al- lo stesso mese dello scorso anno. Negli ultimi dodici mesi disponi- bili, il paese di Juan Valdez ha avuto, in totale, un raccolto di 8 mi- lioni di sacchi circa: poco, in confronto alle medie di 11-12 milioni di sacchi registrate nei primi anni duemila. Ma pur sempre il 9% in più rispetto al volume nei dodici mesi immediatamente precedenti. E, ciò che più conta, Fedecafé ritiene che il prossimo raccolto possa attestarsi attorno ai 10 milioni di sacchi, con un incremento di 2,3 milioni rispetto ai minimi storici del 2012. -

Serving Temperatures of Best-Selling Coffees in Two Segments Of

foods Article Serving Temperatures of Best-Selling Coffees in Two Segments of the Brazilian Food Service Industry Are “Very Hot” Ian C. C. Nóbrega 1,* , Igor H. L. Costa 1 , Axel C. Macedo 1, Yuri M. Ishihara 1 and Dirk W. Lachenmeier 2,* 1 Department of Food Engineering, Universidade Federal da Paraíba (UFPB), João Pessoa, Paraiba 58051-900, Brazil; [email protected] (I.H.L.C.); [email protected] (A.C.M.); [email protected] (Y.M.I.) 2 Chemisches und Veterinäruntersuchungsamt (CVUA) Karlsruhe, Weissenburger Str. 3, 76187 Karlsruhe, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected] (I.C.C.N.); [email protected] (D.W.L.) Received: 29 June 2020; Accepted: 31 July 2020; Published: 3 August 2020 Abstract: The International Agency for Research on Cancer has classified the consumption of “very hot” beverages (temperature >65 ◦C) as “probably carcinogenic to humans”, but there is no information regarding the serving temperature of Brazil’s most consumed hot beverage—coffee. The serving temperatures of best-selling coffee beverages in 50 low-cost food service establishments (LCFS) and 50 coffee shops (CS) were studied. The bestsellers in the LCFS were dominated by 50 mL shots of sweetened black coffee served in disposable polystyrene (PS) cups from thermos flasks. In the CS, 50 mL shots of freshly brewed espresso served in porcelain cups were the dominant beverage. The serving temperatures of all beverages were on average 90% and 68% above 65 ◦C in the LCFS and CS, respectively (P95 and median value of measurements: 77 and 70 ◦C, LCFS; 75 and 69 ◦C, CS). -

Growing Types and Interesting Flavors

A COFFEE CLOSEUP; PART 2: GROWING TYPES AND INTERESTING FLAVORS 2018 • TREND INSIGHT REPORT As we mentioned in our first Coffee Closeup (Who, When & Why), coffee consumption in America is not only consistent – it’s consistently high. The average coffee drinker has more than 3 cups each day. In this closeup on coffee, we’ll zero in on the growth and expansion of formats as well as some incredibly unique and innovative flavors hitting the market. WHAT TYPES OF COFFEE ARE CONSUMERS DRINKING? Traditional hot coffee is still the most popular format, however, its losing market share to new coffee types. For example, 21% of consumers claim to have tried cold brew coffee, which is up 6% YTD. Additionally, 8% of consumers have tried flat white varieties, and 5% claim to have tried nitrogen carbonated coffee. Gourmet beverages such as these are driving the increase in past-day coffee consumption. From 2016 to 2017 the number of people reporting having a gourmet coffee drink in the past day rose 10 points from 31% to 41%. What is a Flat White? Espresso-based beverages such as a flat white are driving past-day coffee consumption. So what exactly is a flat white? It’s an espresso-based beverage prepared by pouring steamed milk over a shot of espresso. Starbucks features a seasonal holiday drink called a Holiday Spice Flat White that returned for a third year. It features Ristretto shots of (concentrated) espresso infused with warm holiday spices AT-HOME PREPARATION “subtle enough to let the coffee really shine through,” according to bustle.com, resulting in a less sweet “experience DRIP COFFEE MAKER 46% (for true coffee lovers) that shouldn’t be missed.” SINGLE-CUP BREWER 29% ESPRESSO Heyday Strong & Smooth Espresso Cold- Brew Coffee is described as strong and super Espresso, which chef and food scientist Matthew smooth. -

Research Report and List of Primary Oral History Sources Can Be Found at the Project Website

The Globalisation of ‘Italian’ Coffee. A Commodity Biography Jonathan Morris The global boom in ‘out of home’ coffee consumption since the mid-1990s has generated renewed interest in the world of coffee among both the academic and general publics. The politics of coffee production and market governance have been investigated from a wide variety of stances, notably by advocates of fair trade for whom coffee forms a potent symbol of the perils of globalisation given the collapse in prices following the liberalisation of the world coffee market1. Historians have been inspired to investigate the social and cultural history of the coffee house2. In Britain, the rise of cappuccino culture has stimulated several publicly funded research projects. Geographers used video footage to compare the ways consumers use contemporary coffee houses with those that Habermas ascribed to their 18th Century forebears; while experts in the visual arts and design have begun an investigation into the interiors of fin- de-siècle coffee houses in Vienna with the intention of comparing these to their early 21st century equivalents3. What these studies have tended to neglect, however, by concentrating upon the settings in which coffee is served, is that this boom has been driven by a profound shift in consumer preferences from traditional ‘national’ coffee beverage styles to those based upon the use of espresso. Espresso is the product of a preparation process which evolved in Italy over the first half of the 20th century, and by now has become almost an icon of the country itself. Italian coffee has thus followed the trajectory of other ‘typical’ foodstuffs, such as pasta and pizza, in projecting Italian cuisine, lifestyle and culture abroad. -

Country-Of-Origin Effect on Coffee Purchase by Italian Consumers

UNIVERSITY OF LJUBLJANA FACULTY OF ECONOMICS MASTER’S THESIS COUNTRY-OF-ORIGIN EFFECT ON COFFEE PURCHASE BY ITALIAN CONSUMERS Ljubljana, March 2016 COK ALENKA AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT The undersigned Alenka COK, a student at the University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Economics, (hereafter: FELU), declare that I am the author of the master’s thesis entitled CONSUMER BEHAVIOUR IN THE ITALIAN COFFEE MARKET: COO EFFECT ON CONSUMER PURCHASE INTENTIONS, written under supervision of full professor Tanja Dmitrović, PhD. In accordance with the Copyright and Related Rights Act (Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia, Nr. 21/1995 with changes and amendments) I allow the text of my master’s thesis to be published on the FELU website. I further declare that: the text of my master’s thesis to be based on the results of my own research; the text of my master’s thesis to be language-edited and technically in adherence with the FELU’s Technical Guidelines for Written Works which means that I o cited and / or quoted works and opinions of other authors in my master’s thesis in accordance with the FELU’s Technical Guidelines for Written Works and o obtained (and referred to in my master’s thesis) all the necessary permits to use the works of other authors which are entirely (in written or graphical form) used in my text; to be aware of the fact that plagiarism (in written or graphical form) is a criminal offence and can be prosecuted in accordance with the Criminal Code (Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia, Nr. -

Ultimate Recipe Book

the ULTIMATE RECIPE BOOK 1 the ULTIMATE STARBUCKS COFFEE RECIPE BOOK Note: Starbucks Coffee is a registered trademark. Table of Contents Beverage Recipes ------------------------------------------------ p 3 Pastry and Coffee Desserts ------------------------------------ p 14 Sauces -------------------------------------------------------------- p 30 2 the ULTIMATE STARBUCKS COFFEE RECIPE BOOK Note: Starbucks Coffee is a registered trademark. Beverage Recipes STARBUCKS FRAPPUCCINO 1/2 cup fresh espresso 2 1/2 cups low fat milk (2 percent) 1/4 cup granulated sugar 1 tablespoon dry pectin Combine all of the ingredients in a pitcher or covered container. Stir or shake until sugar is dissolved. Chill and serve cold. Makes 24 ounces. To make the "Mocha" variety: Add a pinch (1/16 teaspoon) of cocoa powder to the mixture before combining. To make espresso with a drip coffee maker and standard grind of coffee: Use 1/3 cup ground coffee and 1 cup of water. Brew once then run coffee through machine again, same grounds. Makes about 1/2 cup fresh espresso to use in the above recipe. STARBUCK'S CHAI TEA 3 cups water 3 cups milk (I use skim) 6-8 black or decaf black tea bags 1/2 cup honey 1 tsp ground cinnamon 1 tsp ground cardamom 1/2 tsp ground nutmeg 1/2 tsp ground cloves (I use less because I don't like too strong a clove taste) 1/2 tsp ground ginger (or a mashed small chunk of fresh) Bring water and milk to a boil. Add other ingredients, return to boil. Turn off heat and let steep for 3-5 minutes. Remove tea bags then filter through fine strainer. -

Valuación De Starbucks Corporation

Universidad de San Andrés Escuela de Administración y Negocios Maestría en Finanzas Valuación de Starbucks Corporation Autor: Alejandro J. Ceroleni DNI: 32.100.194 Director de Tesis: Javier P. Epstein Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Diciembre de 2016 Maestría en Finanzas Tesis de Valuación Año 2016 Alejandro Javier Ceroleni Contenido Definiciones, aclaraciones y abreviaciones ................................................................................... 3 Resumen ejecutivo ........................................................................................................................ 5 Descripción del negocio ................................................................................................................ 6 Clasificación de las ventas por tipo de producto ...................................................................... 6 Cadena de valor ......................................................................................................................... 7 Clasificación de las ventas por segmento operativo ................................................................. 8 Clasificación de las ventas según el modelo de crecimiento .................................................... 9 Creación de valor .................................................................................................................... 10 Historia de Starbucks .............................................................................................................. 11 Howard Schultz: visión e influencia en el crecimiento -

Design Patenting by Organizations, CY 2013

DESIGN PATENTING BY ORGANIZATIONS 2013 March 2014 U.S. PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE ELECTRONIC INFORMATION PRODUCTS DIVISION - PTMT P.O. BOX 1450 ALEXANDRIA, VA 22313-1450 tel (571) 272-5600 / FAX (571) 273-0110 A PATENT TECHNOLOGY MONITORING TEAM REPORT Design Patenting By Organizations 2013 This report, prepared from the Technology Assessment and Forecast (TAF) database, profiles design patents granted during calendar year 2013. Part A1 Part A1 presents patent counts by origin, U.S. and foreign. Individual counts are also presented for each of the top 36 patenting countries. Patent origin is determined by the residence of the first-named inventor listed on a patent. Patent ownership-category information reflects ownership at the time of patent grant and does not reflect subsequent changes in ownership. If more than one assignee (the entity, if any, to which the patent rights have been legally assigned) was declared at the time of grant, a patent is attributed to the ownership-category of the first-named assignee. The "U.S. Corporations" and "Foreign Corporations" ownership categories count predominantly corporate patents; however, patents assigned to other organizations such as small businesses, nonprofit organizations, universities, etc. are also included in these categories. While the "U.S. Government" ownership category includes only patents granted to the Federal Government, no such distinction is made for the "Foreign Government" ownership category. The "U.S. Individuals" and "Foreign Individuals" ownership categories include patents for which ownership was assigned to an individual as well as patents for which no assignment of ownership was made at the time of grant (i.e., ownership was retained by the inventor(s)).