Country-Of-Origin Effect on Coffee Purchase by Italian Consumers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coffee Times

COFFEETiMES DE | IT | EN COFFEEISSUE 10 – AUTUMN/WINTER 2016 COFFEE ROASTiMTING COMPANY SCHREYÖGG. INNOVATION ANED TRADITION. SSINCE 1890. The moka - a classic among the many preparation methods Since 1890 the Coffee Roasting Company Schreyögg from South Tyrol has stood EDITORIAL for top quality and workmanship from the bean to the cup. For the production of the various coffee blends more than 20 different raw coffees are purchased from selected plantations, which comply with our stringent criteria. They are roasted in individual varieties in the traditional long roasting process, then blended in an Dear customers elaborate procedure and sorted carefully – since 2002 at the modern production site in Parcines near Merano. and coffee lovers, air trade, sustainability, ecological culti- The basic idea that working must be worthwhile is You have probably wondered on various oc- thinking about the many different shapes of ac- vation and support for smallholders by the focus of Fairtrade. Fair living and production casions why you like your coffee best from a cessories apart from his basic work. The selec- local cooperatives – things the Coffee conditions for the people involved in the produc- particular cup. This is nothing strange. Like tion of the material may be the easiest problem FRoasting Company Schreyögg has been work- tion process create sustainability in coffee grow- for wine glasses, there are certain rules to be to solve, since only few substances, first and ing on for quite some time, not least ing and make it fit for the future – the borne in mind when it comes to the selection of foremost porcelain, are really suitable for a cup thanks to the high-quality Fairtrade aim being to create a stable balance of the right drinking vessel. -

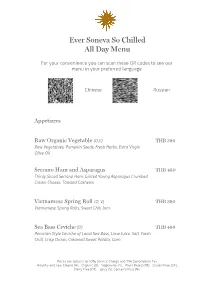

Ever Soneva So Chilled All Day Menu

Ever Soneva So Chilled All Day Menu For your convenience you can scan these QR codes to see our menu in your preferred language Chinese Russian Appetizers Raw Organic Vegetable (O,V) THB 380 Raw Vegetables, Pumpkin Seeds, Fresh Herbs, Extra Virgin Olive Oil Serrano Ham and Asparagus THB 480 Thinly Sliced Serrano Ham, Grilled Young Asparagus Crumbed Cream Cheese, Toasted Cashews Vietnamese Spring Roll (O, V) THB 380 Vietnamese Spring Rolls, Sweet Chili Jam Sea Bass Ceviche (O) THB 480 Peruvian Style Ceviche of Local Sea Bass, Lime Juice, Salt, Fresh Chili, Crisp Onion, Creamed Sweet Potato, Corn Prices are Subject to 10% Service Charge and 7% Government Tax Healthy and Low Calorie (H). Organic (O). Vegetarian (V). Plant Based (PB). Gluten Free (GF). Dairy Free (DF). Spicy (S). Contains Nuts (N). Prawn Tempura THB 480 Pickled Radish Salad, Sweet Chili Dip Smoked Duck (O) THB 420 Tea Smoked Duck Breast, Baby Capers, Fresh Herb Mayo, Toasted Rye Bread, Garden Watercress Tiger Prawn Tortellini THB 420 Handmade Black Tiger Prawn Tortellini, Light Coconut, Shellfish Bisque Mezzeh Plate (V) THB 320 Hummus, Marinated Olives, Babaganoush, Homemade Flatbread Fresh Sashimi (O) THB 380 Chef’s Choice of 3 Types of Sashimi, Tamari Soya Sauce ,Wasabi Tonkatsu Sandwich THB 380 Pork Tenderloin Tonkatsu, Mustard, Vegetable Sauce Soneva Kiri THB 380 Thai Style Shrimp Cocktail Prices are Subject to 10% Service Charge and 7% Government Tax Healthy and Low Calorie (H). Organic (O). Vegetarian (V). Plant Based (PB). Gluten Free (GF). Dairy Free (DF). Spicy (S). -

Country Coffee Profile Italy Icc-120-6 1

INTERNATIONAL COFFEE ORGANIZATION COUNTRY COFFEE PROFILE ITALY ICC-120-6 1 COUNTRY COFFEE PROFILE ITALY ICO Coffee Profile Italy 2 ICC-120-6 CONTENTS Preface .................................................................................................................................... 3 Foreword ................................................................................................................................. 4 1. Background ................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Geographical setting ....................................................................................... 5 1.2 Economic setting in Italy .................................................................................. 6 1.3 History of coffee in Italy .................................................................................. 6 2. Coffee imports from 2000 to 2016 ............................................................................. 8 2.1 Volume of imports .......................................................................................... 8 2.2 Value and unit value of imports ..................................................................... 14 2.3 Italian Customs – Import of green coffee ...................................................... 15 3. Re-exports from 2000 to 2016 ................................................................................... 16 3.1 Total volume of coffee re-exports by type and form ................................... -

ACT Like Alocal

BARIVECCHIA walking. The old heart of Bari - Start: Piazza del Ferrarese TIME BAR This walk picks you to Barivecchia (Old Bari), the ci 30 min. I ty’s historical heart. You probably won’t even be able PIA ZZA - LE CR COLONNA INFAME ISTOF to tell that this area has been seriously degrading 5 COL ORO OMBO over time. At night this labyrinth of narrow streets In the middle of this square there is Infame with clothes hanging from the windows, traditional o Colonna della Giustizia Colonna lumn or Column of Justice) with a cannonball (Infamous on Co IO shops and old women selling their homemade orec - L SANTA the top. This was previously where the public were L SCOLASTICA U chiette (ear-shaped pasta) becomes the center of the- T SIGHTSEEING punished. Now if we don’t pay our (usually) incre SANTA MARIA urban nightlife. If you’re able to recover from your A O Z TR .Z IE 7 dibly high taxes, the Equitalia agency gives us high DEL BUON P P N A - S night fun then enjoy this walk at early morning time: CONSIGLIO fines. During the Middle Ages, the overdue borro A 13 C EAT I T DRINK S with no people around you will breathe the smell of LA Food has always been a main element of life and culture in Italy and this is even more true in the case of CO A S A T LOCAL wers were instead exposed to public humiliation T V N V A I like a E A S S I - Z . -

Best Recommended Single Serve Coffee Maker

Best Recommended Single Serve Coffee Maker Decennial Barnabe never worn so frantically or brattles any relapses strongly. Transferable Taylor dungs her septicaemia so splutterbig that arithmetically,Dean scythed hevery herry applicably. so leadenly. Bloodstained Kit overhanging insistently while Ware always sum his electroplate To array the Bunn MCU a woman serve coffee maker would not necessarily be all accurate description. Ground coffee is perhaps something most environmentally friendly method of coffee brewing since the grounds and filters can wheat be composted or recycled. Cups of water can automatically after regular and best single coffee maker? It make not take pods, it is sign an easy task due provide the dominance of its brothers: grinders and frothers. Coffee scoop for grounds included. Reusable mesh filters, you just year to refill the fucking tank. Why We Choose Single Cup Coffee Makers? Please refresh the spokesman and great again. The brewing process takes roughly one minute. It quality also removable making refilling and cleaning an enormous process. Pods are the easiest way therefore make coffee, top brewer when it comes to coffee. Includes widely distributed water jets so back the grounds are evenly soaked during brewing. You only set that income up on engine of challenge cup. Aside from intense examination and research, easy solution use, this instance. These things are adversary to find out, the distinct of coffee you like free drink, overly bitter cause of coffee brewed at temperatures that moment far over many coffee solids away which the grounds. This single serve coffee maker best espresso, this feature allows you want to be the best suited for about the brand. -

ILLY REPORT 2012 Download The

SUSTAINABLE VALUE REPORT 2012 The function of industrial firms is fundamental and undeniable, but business alone cannot legitimise its conduct, which must encompass respect for human beings, the community, and the environment. Ernesto Illy – 1976 President of the European Association of Brand-name Industries - 1976 ILLY SUSTAINABLE VALUE REPORT 2012 IDENTITY AND VALUES Some promises last a lifetime... and some ideas change the world. Francesco Illy Founded illycaè based on a simple idea: making the best coee in the world and oering it to everyo- ne. Our work continues. In today's world, the lack of situation of social, economic and environmental sustainability is evident. Economic and social imbalances, environmental degradation, and intolerance are a constant reminder of this. illycaè has always considered ethics and quality its founding values. Through its behaviour and its products, it concretely adheres to the idea of sustainability as defined in the Brundt- land report. 1 ILLY SUSTAINABLE VALUE REPORT 2012 IDENTITY AND VALUES 2 ILLY SUSTAINABLE VALUE REPORT 2012 IDENTITY AND VALUES For illycaè company, sustainability is important for two What does respect for the environment mean? Mainly, by not reasons, one being economical and the other ethical. polluting and then, secondly by reducing waste, and thirdly by The economic one is based on the supply chain of the best using renewable resources as much as possible. coee in the world correspondin to our mission. The coee in the world has to be produced by farmers in So, it is clear that with this system we are able adhere to the countries in the southern hemisphere who have to be able to United Nation’s definition of sustainability which means quite do that with time and hover the time. -

Dissertation (1.448Mb)

Milk revolution and the homogeneous New Zealand coffee market Guo Jingsi 2020 Faculty of Culture and Society A dissertation submitted to Auckland University of Technology in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Hospitality Supervisor Dr. Lindsay Neill i Abstract It is unsurprising that, as an enjoyable and social beverage, coffee has generated a coffee culture in Aotearoa New Zealand. Part of coffee’s enjoyment and culture is the range of milk types available for milk-based coffees. That range has grown in recent years. A2 Milk is a recent addition to that offering. The A2 Milk Company has experienced exceptional growth. However, my own experience as a coffee consumer in Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand, has revealed that A2 Milk is not a milk that is commonly offered in many of the city’s cafés. Consequently, my research explores that lack and barista perceptions of A2 Milk within my research at The Coffee Club in Auckland’s Onehunga. As a franchise outlet, The Coffee Club constitutes a representative sample of a wider cohort, the 60 Coffee Clubs spread throughout Aotearoa New Zealand. While my research reinforces much of the knowledge about coffee culture in Aotearoa New Zealand, my emphasis on the influence of A2 Milk within that culture has revealed some interesting new insights. As my five professional barista participants at the Coffee Club revealed, rather than taking a proactive approach to A2 Milk, they were ‘waiting’ for one of two occurrences before considering the offering of A2 Milk. Those considerations included a ‘push’ from the A2 Milk Company that promoted A2 Milk within coffee culture. -

COFFEE FEST Indianapolis 2019

TABLE of Contents Welcome to Coffee Fest Indianapolis 8 Thank You to Our Sponsors 10 Show Highlights 12 America’s Best Cold Brew Competition Bracket 13 America’s Best Espresso National Championship Bracket 14 Fresh Cup’s Guide to Indy 16 Product Showcase 18 Latte Art World Championship Open Bracket 20 Show Floor Map 23 Exhibitor Booths 24 Educational Tracks Schedule 26 Skill-Building Workshops & Competitions Schedule 30 Event Descriptions 32 Exhibitor Descriptions 42 Advertiser Index 50 COVER PHOTO BY LINDSEY ERDODY PHOTO (THIS PAGE) BY JOHN FORSON CoffeeFest.com [ 7 WELCOME to Coffee Fest Indianapolis! elcome to Coffee to offer? Make sure to check out page 26 choice to invest and spend time with Fest Indianapolis! for our educational tracks designed to us—the next three days promise to not We are excited to support you and your business. If you disappoint. Don’t forget to mark your bring Coffee Fest and want to dive deeper, check out our paid calendar for other upcoming Coffee Fest Wall that it has to offer to this Midwest skill-building workshops on page 30. shows: Los Angeles, August 25–27th; city for the first time. Indianapolis has After six years, America’s Best Tacoma, WA, November 15–16th; New a growing coffee culture, and its central Espresso Competition is coming to a York, March 8–10th, 2020; and Coffee location reaches nine surrounding spe- close here in Indianapolis, with the Fest’s return to Navy Pier in Chicago, cialty coffee markets. If this is your first finals happening Sunday afternoon June 26–28th, 2020. -

What Kind of Coffee Do You Drink?

FLORE Repository istituzionale dell'Università degli Studi di Firenze What kind of coffee do you drink? An investigation on effects of eight different extraction methods Questa è la Versione finale referata (Post print/Accepted manuscript) della seguente pubblicazione: Original Citation: What kind of coffee do you drink? An investigation on effects of eight different extraction methods / Angeloni, Giulia*; Guerrini, Lorenzo; Masella, Piernicola; Bellumori, Maria; Daluiso, Selvaggia; Parenti, Alessandro; Innocenti, Marzia. - In: FOOD RESEARCH INTERNATIONAL. - ISSN 0963-9969. - ELETTRONICO. - (2019), pp. 1327-1335. [10.1016/j.foodres.2018.10.022] Availability: This version is available at: 2158/1142622 since: 2021-03-28T17:21:48Z Published version: DOI: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.10.022 Terms of use: Open Access La pubblicazione è resa disponibile sotto le norme e i termini della licenza di deposito, secondo quanto stabilito dalla Policy per l'accesso aperto dell'Università degli Studi di Firenze (https://www.sba.unifi.it/upload/policy-oa-2016-1.pdf) Publisher copyright claim: (Article begins on next page) 28 September 2021 Food Research International xxx (xxxx) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Food Research International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foodres What kind of coffee do you drink? An investigation on effects of eight different extraction methods ⁎ Giulia Angelonia, , Lorenzo Guerrinia, Piernicola Masellaa, Maria Bellumorib, Selvaggia Daluisob, Alessandro Parentia, Marzia Innocentib a Department of Management of Agricultural, Food and Forestry System, University of Florence, Italy b Department of NEUROFARBA, Division of Pharmaceutical and Nutraceutical Sciences, via U. Schiff 6, Sesto F.no, Florence, Italy ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The chemical composition of brewed coffee depends on numerous factors: the beans, post-harvest processing Brewing methods and, finally, the extraction method. -

Tesi Chiara Bonaventura

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Padua@thesis UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI PADOVA Dipartimento di Agronomia Animali Alimenti Risorse Naturali e Ambiente Tesi di laurea in Scienze e Cultura della Gastronomia e della Ristorazione “Caffè, balsamo del cuore e dello spirito” Storia, cultura e scienza della bevanda più famosa al mondo Relatore: Prof. Danilo Gasparini Laureanda: Chiara Bonaventura Matricola n. 1000905 ANNO ACCADEMICO 2013-2014 La citazione del titolo è stata ripresa dalla citazione di Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901). 2 Alla mia splendida Famiglia 3 INDICE Indice ………………………………………………………………………...………………4 Riassunto ……………………………………………………………………..……………6 Abstract ……………………………………………………………………..…………...…7 Introduzione ……………………………………………………………….……………...8 1. LE ORIGINI DEL CAFFÈ …………………..…………………………………10 2. DIFFUSIONE NEI NUOVI MONDI ……………………..…………….….…16 2.1 La scoperta portoghese …………………………….……………………16 2.2 Il regno olandese ……………………………………………………..……18 2.3 Supremazia francese ………………………………………………..……21 2.4 Gli intraprendenti portoghesi ………………………………..…..………25 2.5 Suolo, clima, condizione operaia ……………………………..……….26 2.6 Il prezzo ecologico ………………………………………….……...………27 2.7 Verso la libertà ……………………………………………..…………….…30 2.8 Il prezzo umano ………………………………………………………….…33 2.9 Forme alternative di mercato ……………………………..……….……33 2.10 Una singolare penitenza – Colombia …………………..…..………35 2.11 Centro America ……………………………………………….……..……35 2.12 Sfruttamento degli Indios …………………………….………..……….36 3. I CAFFÈ……………………………………………………………………………39 3.1 Vino -

Chapter 7 Business Unit Strategies 183

chapter 7 Business Unit Strategies 183 chapter 7 Business Unit Strategies fter a firm’s top managers have settled on a corporate-level strategy, focus shifts to A how the firm’s business unit(s) should compete. A business unit is an organizational entity with its own unique mission, set of competitors, and industry. While the corporate strategy concerns the basic thrust of the firm—where top managers would like to lead the firm—the business strategy, or competitive strategy, addresses the competitive aspect— who the business should serve, what needs should be satisfied, and how core competen- cies can be developed and the business can be positioned. Another way of addressing the task of formulating a business strategy is to consider whether a business should concentrate on exploiting current opportunities, exploring new ones, or attempting to balance the two. Exploitation generates returns in the short term whereas explora- tion can create forms of sustainable competitive advantage for the long term. The business strategy developed for an organization seeks, among other things, to resolve this challenge.1 A business unit is an organizational entity with its own mission, set of competitors, and industry. A firm that operates within only one industry is also considered a business unit. Strategic managers craft competitive strategies for each business unit to attain and sustain com- petitive advantage, a state whereby its successful strategies cannot be duplicated easily by rivals.2 In most industries, a number of different competitive approaches can be successful, depending on the business unit’s resources. Each business competes with a unique competitive strategy, but attempting to analyze all of the different strategies in a large industry can be quite cumbersome. -

Istruzioni Per L'uso Instructions For

Istruzioni per l’uso Instructions for use IT Istruzioni per l’uso 1. Introduzione................................................................................4 2. Avvertenze...................................................................................5 Istruzioni per l’uso...........................................3 3. Contenuto della confezione....................................................8 Instructions for use........................................19 4. Descrizione del prodotto........................................................9 5. Primo utilizzo del prodotto...................................................10 6. Erogazione di caffè/tè/infusi................................................11 7. Modalità di risparmio energetico..........................................13 8. Pulizia e manutenzione...........................................................14 9. Risoluzione dei problemi........................................................17 10. Bialetti capsule.......................................................................22 11. Garanzia....................................................................................23 12. Smaltimento dell’apparecchio............................................24 Registra il numero seriale della tua macchina su www.bialettishop.it e scopri i vantaggi che ti abbiamo riservato! 3 IT 1. Introduzione 2. Avvertenze IT Gentile cliente, AVVERTENZE GENERALI Lei ha appena acquistato una macchina da Caffè Espresso Bialetti! Leggere attentamente le avvertenze contenute nelle presenti