Sugar Or Salt? Ionic and Covalent Bonds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Courses of Study for Generic Elective 'B

COURSES OF STUDY FOR GENERIC ELECTIVE 'B. Sc, HODs' PROGRAMME IN "CHEMISTRY" GENERIC ELECTIVE All Four Generic Papers (One paper to be studied in each semester) of Chemistry to be studied by the Students of Other than Chemistry Honours. SEM- I Generic Elective Papers (GE-l) (Minor-Chemistry) (any four) for other Departments/ Disciplines: (Credit: 06 each) GE: ATOMIC STRUCTURE, BONDING, GENERAL ORGANIC CHEMISTRY & ALIPHATIC HYDROCARBONS (Credits: Theory-04, Practicals-02) Theory: 60 Lectures Section A: Inorganic Chemistry-I (30 Periods) Atomic Structure: Review of Bohr's theory and its limitations, dual behaviour of matter and radiation, de Broglie's relation, Heisenberg Uncertainty principle. Hydrogen atom spectra. Need of a new approach to Atomic structure. What is Quantum mechanics? Time independent Schrodinger equation and meaning of various terms in it. Significance of !fl and !fl2, Schrodinger equation for hydrogen atom. Radial and angular parts of the hydogenic wavefunctions (atomic orbitals) and their variations for Is, 2s, 2p, 3s, 3p and 3d orbitals (Only graphical representation). Radial and angular nodes and their significance. Radial distribution functions and the concept of the most probable distance with special reference to Is and 2s atomic orbitals. Significance of quantum numbers, orbital angular momentum and quantum numbers m I and m«. Shapes of s, p and d atomic orbitals, nodal planes. Discovery of spin, spin quantum number (s) and magnetic spin quantum number (ms). Rules for filling electrons in various orbitals, Electronic configurations of the atoms. Stability of half-filled and completely filled orbitals, concept of exchange energy. Relative energies of atomic orbitals, Anomalous electronic configurations. -

Topological Analysis of the Metal-Metal Bond: a Tutorial Review Christine Lepetit, Pierre Fau, Katia Fajerwerg, Myrtil L

Topological analysis of the metal-metal bond: A tutorial review Christine Lepetit, Pierre Fau, Katia Fajerwerg, Myrtil L. Kahn, Bernard Silvi To cite this version: Christine Lepetit, Pierre Fau, Katia Fajerwerg, Myrtil L. Kahn, Bernard Silvi. Topological analysis of the metal-metal bond: A tutorial review. Coordination Chemistry Reviews, Elsevier, 2017, 345, pp.150-181. 10.1016/j.ccr.2017.04.009. hal-01540328 HAL Id: hal-01540328 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-01540328 Submitted on 16 Jun 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Topological analysis of the metal-metal bond: a tutorial review Christine Lepetita,b, Pierre Faua,b, Katia Fajerwerga,b, MyrtilL. Kahn a,b, Bernard Silvic,∗ aCNRS, LCC (Laboratoire de Chimie de Coordination), 205, route de Narbonne, BP 44099, F-31077 Toulouse Cedex 4, France. bUniversité de Toulouse, UPS, INPT, F-31077 Toulouse Cedex 4, i France cSorbonne Universités, UPMC, Univ Paris 06, UMR 7616, Laboratoire de Chimie Théorique, case courrier 137, 4 place Jussieu, F-75005 Paris, France Abstract This contribution explains how the topological methods of analysis of the electron density and related functions such as the electron localization function (ELF) and the electron localizability indicator (ELI-D) enable the theoretical characterization of various metal-metal (M-M) bonds (multiple M-M bonds, dative M-M bonds). -

Suppression Mechanisms of Alkali Metal Compounds

SUPPRESSION MECHANISMS OF ALKALI METAL COMPOUNDS Bradley A. Williams and James W. Fleming Chemistry Division, Code 61x5 US Naval Research Lnhoratory Washington, DC 20375-5342, USA INTRODUCTION Alkali metal compounds, particularly those of sodium and potassium, are widely used as fire suppressants. Of particular note is that small NuHCOi particles have been found to be 2-4 times more effective by mass than Halon 1301 in extinguishing both eountertlow flames [ I] and cup- burner flames [?]. Furthermore, studies in our laboratory have found that potassium bicarbonate is some 2.5 times more efficient by weight at suppression than sodium bicarhonatc. The primary limitation associated with the use of alkali metal compounds is dispersal. since all known compounds have very low volatility and must he delivered to the fire either as powders or in (usually aqueous) solution. Although powders based on alkali metals have been used for many years, their mode of effective- ness has not generally been agreed upon. Thermal effects [3],namely, the vaporization of the particles as well as radiative energy transfer out of the flame. and both homogeneous (gas phase) and heterogeneous (surface) chemistry have been postulated as mechanisms by which alkali metals suppress fires [4]. Complicating these issues is the fact that for powders, particle size and morphology have been found to affect the suppression properties significantly [I]. In addition to sodium and potassium, other alkali metals have been studied, albeit to a consider- ably lesser extent. The general finding is that the suppression effectiveness increases with atomic weight: potassium is more effective than sodium, which is in turn more effective than lithium [4]. -

Sodium Aluminium Silicate (Tentative)

SODIUM ALUMINIUM SILICATE (TENTATIVE) th Prepared at the 80 JECFA and published in FAO JECFA Monographs 17 (2015), superseding tentative specifications prepared at the 77th JECFA (2013) and published in FAO JECFA Monographs 14 (2013). An ADI 'not specified' for silicon dioxide and certain silicates was established at the 29th JECFA (1985). A PTWI of 2 mg/kg bw for total aluminium was established at the 74th JECFA (2011). The PTWI applies to all aluminium compounds in food, including food additives. Information required: Functional uses other than anticaking agent, if any, and information on the types of products in which it is used and the use levels in these products Data on solubility using the procedure documented in the “Compendium of Food Additives Specifications, Vol. 4, Analytical methods” Data on the impurities soluble in 0.5 M hydrochloric acid, from a minimum of five batches. If a different extraction and determination method is used, provide data along with details of method and QC data. Suitability of the analytical method for the determination of aluminium, silicon and sodium using the proposed “Method of assay” along with data, from a minimum of five batches, using the proposed method. If a different method is used, provide data along with details of the method and QC data. SYNONYMS Sodium silicoaluminate; sodium aluminosilicate; aluminium sodium silicate; silicic acid, aluminium sodium salt; INS No. 554 DEFINITION Sodium aluminium silicate is a series of amorphous hydrated sodium aluminium silicates with varying proportions of Na2O, Al2O3 and SiO2. It is manufactured by, precipitation process, reacting aluminium sulphate and sodium silicate. -

Ozone Questions and Answers

FRom THE WORLd’s #1 IN-flooR CLEANING SYSTEMS CompANY OZONE QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS WHY OZONATE MY POOL OR SPA? ANSWER: Pool owners who are concerned about the harmful effects of chlorine will be interested in reducing chlorine levels in the water. In particular, pools with chlorine-only systems can be harmful as the skin’s pores open up and ingest chlorine into the body. In some cases competitive swimmers will refuse to swim in a chlorine-only pool, and Olympic pools are generally ozonated for this reason. WHAT IS OZONE? ANSWER: Ozone is active oxygen, O3. Ozone occurs naturally in the earth’s atmosphere to protect us from the sun’s harmful rays. As single oxygen atoms are very unstable, they travel around in pairs which are written scientifically as O2. Ozone is made up of three oxygen atoms written as O3. When activated, it is called Triatomic Oxygen. HOW DOES OZONE WORK? ANSWER: Ozone is up to 50 times more powerful at killing bacteria and viruses than traditional pool chemicals and up to 3000 times faster. Ozone is faster than chlorine at killing bacteria because chlorine needs to diffuse through the cell wall and disrupt the bacteria’s metabolism. Ozone, however ruptures the cell wall from the outside causing the cell’s contents to fall apart. This process is known as “cellular lyses”. This process takes place in about 2 seconds. With ozone, after the destruction of the cell all that is left are carbon dioxide, cell debris and water. Once this process is complete ozone reverts back to oxygen O2; which makes ClearO3 a very eco-friendly product. -

Chapter 4, Lesson 5: Energy Levels, Electrons, and Ionic Bonding

Chapter 4, Lesson 5: Energy Levels, Electrons, and Ionic Bonding Key Concepts • The attractions between the protons and electrons of atoms can cause an electron to move completely from one atom to the other. • When an atom loses or gains an electron, it is called an ion. • The atom that loses an electron becomes a positive ion. • The atom that gains an electron becomes a negative ion. • A positive and negative ion attract each other and form an ionic bond. Summary Students will look at animations and make drawings of the ionic bonding of sodium chloride (NaCl). Students will see that both ionic and covalent bonding start with the attractions of pro- tons and electrons between different atoms. But in ionic bonding, electrons are transferred from one atom to the other and not shared like in covalent bonding. Students will use Styrofoam balls to make models of the ionic bonding in sodium chloride (salt). Objective Students will be able to explain the process of the formation of ions and ionic bonds. Evaluation The activity sheet will serve as the “Evaluate” component of each 5-E lesson plan. The activity sheets are formative assessments of student progress and understanding. A more formal summa- tive assessment is included at the end of each chapter. Safety Be sure you and the students wear properly fitting goggles. Materials for Each Group • Black paper • Salt • Cup with salt from evaporated saltwater • Magnifier • Permanent marker Materials for Each Student • 2 small Styrofoam balls • 2 large Styrofoam balls • 2 toothpicks ©2016 American Chemical Society Middle School Chemistry - www.middleschoolchemistry.com 337 Note: In an ionically bonded substance such as NaCl, the smallest ratio of positive and negative ions bonded together is called a “formula unit” rather than a “molecule.” Technically speaking, the term “molecule” refers to two or more atoms that are bonded together covalently, not ioni- cally. -

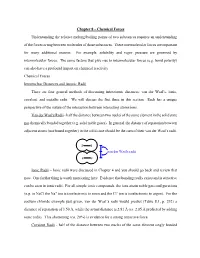

Chemical Forces Understanding the Relative Melting/Boiling Points of Two

Chapter 8 – Chemical Forces Understanding the relative melting/boiling points of two substances requires an understanding of the forces acting between molecules of those substances. These intermolecular forces are important for many additional reasons. For example, solubility and vapor pressure are governed by intermolecular forces. The same factors that give rise to intermolecular forces (e.g. bond polarity) can also have a profound impact on chemical reactivity. Chemical Forces Internuclear Distances and Atomic Radii There are four general methods of discussing interatomic distances: van der Waal’s, ionic, covalent, and metallic radii. We will discuss the first three in this section. Each has a unique perspective of the nature of the interaction between interacting atoms/ions. Van der Waal's Radii - half the distance between two nuclei of the same element in the solid state not chemically bonded together (e.g. solid noble gases). In general, the distance of separation between adjacent atoms (not bound together) in the solid state should be the sum of their van der Waal’s radii. F F van der Waal's radii F F Ionic Radii – Ionic radii were discussed in Chapter 4 and you should go back and review that now. One further thing is worth mentioning here. Evidence that bonding really exists and is attractive can be seen in ionic radii. For all simple ionic compounds, the ions attain noble gas configurations (e.g. in NaCl the Na+ ion is isoelectronic to neon and the Cl- ion is isoelectronic to argon). For the sodium chloride example just given, van der Waal’s radii would predict (Table 8.1, p. -

Multidisciplinary Design Project Engineering Dictionary Version 0.0.2

Multidisciplinary Design Project Engineering Dictionary Version 0.0.2 February 15, 2006 . DRAFT Cambridge-MIT Institute Multidisciplinary Design Project This Dictionary/Glossary of Engineering terms has been compiled to compliment the work developed as part of the Multi-disciplinary Design Project (MDP), which is a programme to develop teaching material and kits to aid the running of mechtronics projects in Universities and Schools. The project is being carried out with support from the Cambridge-MIT Institute undergraduate teaching programe. For more information about the project please visit the MDP website at http://www-mdp.eng.cam.ac.uk or contact Dr. Peter Long Prof. Alex Slocum Cambridge University Engineering Department Massachusetts Institute of Technology Trumpington Street, 77 Massachusetts Ave. Cambridge. Cambridge MA 02139-4307 CB2 1PZ. USA e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] tel: +44 (0) 1223 332779 tel: +1 617 253 0012 For information about the CMI initiative please see Cambridge-MIT Institute website :- http://www.cambridge-mit.org CMI CMI, University of Cambridge Massachusetts Institute of Technology 10 Miller’s Yard, 77 Massachusetts Ave. Mill Lane, Cambridge MA 02139-4307 Cambridge. CB2 1RQ. USA tel: +44 (0) 1223 327207 tel. +1 617 253 7732 fax: +44 (0) 1223 765891 fax. +1 617 258 8539 . DRAFT 2 CMI-MDP Programme 1 Introduction This dictionary/glossary has not been developed as a definative work but as a useful reference book for engi- neering students to search when looking for the meaning of a word/phrase. It has been compiled from a number of existing glossaries together with a number of local additions. -

Starter for Ten 3

Learn Chemistry Starter for Ten 3. Bonding Developed by Dr Kristy Turner, RSC School Teacher Fellow 2011-2012 at the University of Manchester, and Dr Catherine Smith, RSC School Teacher Fellow 2011-2012 at the University of Leicester This resource was produced as part of the National HE STEM Programme www.rsc.org/learn-chemistry Registered Charity Number 207890 3. BONDING 3.1. The nature of chemical bonds 3.1.1. Covalent dot and cross 3.1.2. Ionic dot and cross 3.1.3. Which type of chemical bond 3.1.4. Bonding summary 3.2. Covalent bonding 3.2.1. Co-ordinate bonding 3.2.2. Electronegativity and polarity 3.2.3. Intermolecular forces 3.2.4. Shapes of molecules 3.3. Properties and bonding Bonding answers 3.1.1. Covalent dot and cross Draw dot and cross diagrams to illustrate the bonding in the following covalent compounds. If you wish you need only draw the outer shell electrons; (2 marks for each correct diagram) 1. Water, H2O 2. Carbon dioxide, CO2 3. Ethyne, C2H2 4. Phosphoryl chloride, POCl3 5. Sulfuric acid, H2SO4 Bonding 3.1.1. 3.1.2. Ionic dot and cross Draw dot and cross diagrams to illustrate the bonding in the following ionic compounds. (2 marks for each correct diagram) 1. Lithium fluoride, LiF 2. Magnesium chloride, MgCl2 3. Magnesium oxide, MgO 4. Lithium hydroxide, LiOH 5. Sodium cyanide, NaCN Bonding 3.1.2. 3.1.3. Which type of chemical bond There are three types of strong chemical bonds; ionic, covalent and metallic. -

Hydraulics Manual Glossary G - 3

Glossary G - 1 GLOSSARY OF HIGHWAY-RELATED DRAINAGE TERMS (Reprinted from the 1999 edition of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials Model Drainage Manual) G.1 Introduction This Glossary is divided into three parts: · Introduction, · Glossary, and · References. It is not intended that all the terms in this Glossary be rigorously accurate or complete. Realistically, this is impossible. Depending on the circumstance, a particular term may have several meanings; this can never change. The primary purpose of this Glossary is to define the terms found in the Highway Drainage Guidelines and Model Drainage Manual in a manner that makes them easier to interpret and understand. A lesser purpose is to provide a compendium of terms that will be useful for both the novice as well as the more experienced hydraulics engineer. This Glossary may also help those who are unfamiliar with highway drainage design to become more understanding and appreciative of this complex science as well as facilitate communication between the highway hydraulics engineer and others. Where readily available, the source of a definition has been referenced. For clarity or format purposes, cited definitions may have some additional verbiage contained in double brackets [ ]. Conversely, three “dots” (...) are used to indicate where some parts of a cited definition were eliminated. Also, as might be expected, different sources were found to use different hyphenation and terminology practices for the same words. Insignificant changes in this regard were made to some cited references and elsewhere to gain uniformity for the terms contained in this Glossary: as an example, “groundwater” vice “ground-water” or “ground water,” and “cross section area” vice “cross-sectional area.” Cited definitions were taken primarily from two sources: W.B. -

Molten Salt Chemistry Workshop

The cover depicts the chemical and physical complexity of the various species and interfaces within a molten salt reactor. To advance new approaches to molten salt technology development, it is necessary to understand and predict the chemical and physical properties of molten salts under extreme environments; understand their ability to coordinate fissile materials, fertile materials, and fission products; and understand their interfacial reactions with the reactor materials. Modern x-ray and neutron scattering tools and spectroscopy and electrochemical methods can be coupled with advanced computational modeling tools using high performance computing to provide new insights and predictive understanding of the structure, dynamics, and properties of molten salts over a broad range of length and time scales needed for phenomenological understanding. The actual image is a snapshot from an ab initio molecular dynamics simulation of graphene- organic electrolyte interactions. Image courtesy of Bobby G. Sumpter of ORNL. Molten Salt Chemistry Workshop Report for the US Department of Energy, Office of Nuclear Energy Workshop Molten Salt Chemistry Workshop Technology and Applied R&D Needs for Molten Salt Chemistry April 10–12, 2017 Oak Ridge National Laboratory Co-chairs: David F. Williams, Oak Ridge National Laboratory Phillip F. Britt, Oak Ridge National Laboratory Working Group Co-chairs Working Group 1: Physical Chemistry and Salt Properties Alexa Navrotsky, University of California–Davis Mark Williamson, Argonne National Laboratory Working -

Oesper's Salt

Notes from the Oesper Collections Oesper’s Salt William B. Jensen Department of Chemistry, University of Cincinnati Cincinnati, OH 45221-0172 Though he passed away in 1977, the name of Ralph Edward Oesper (figure 1) is still pervasive in the Uni- versity of Cincinnati Department of Chemistry. We have the Oesper Professorship of Chemical Education and History of Chemistry, the annual Oesper Sympo- sium and Award, the Oesper Chemistry and Biology Library, and the Oesper Collections in the History of Chemistry, to name but a few of the institutions and activities funded by Oesper’s legacy to the department. Despite this, however, few of the current faculty and students are aware of Oesper’s activities as a chemist or of the fact that he is, to the best of my knowledge, the only member of our department – past or present – to have a chemical compound named in his honor. Best remembered today for his work in the field of the history of chemistry, most of Oesper’s professional activities as a practicing chemist centered on the field of analytical chemistry, where he is responsible for having translated several important German mono- Figure 1. Ralph Edward Oesper (1884-1977). graphs – the most famous of which were perhaps Fritz Feigl’s various books on the technique of spot analysis (1). If Oesper had a particular specialty of his own, it metric analysis. In 1934 he introduced a new indicator was the use of oxidation-reduction reactions in volu- (naphthidine) for chromate titrations (2) and in 1938 he translated the German monograph Newer Methods of Volumetric Analysis (3).