Mercury and Mercury Compounds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

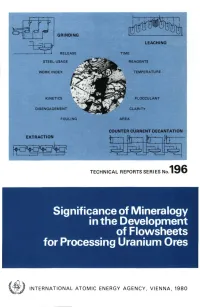

Significance of Mineralogy in the Development of Flowsheets for Processing Uranium Ores

JfipwK LEACHING TIME REAGENTS TEMPERATURE FLOCCULANT CLARITY AREA COUNTER CURRENT DECANTATION It 21 21 J^^LJt TECHNICAL REPORTS SERIES No.19 6 Significance of Mineralogy in the Development of Flowsheets for Processing Uranium Ores \W# INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, VIENNA, 1980 SIGNIFICANCE OF MINERALOGY IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF FLOWSHEETS FOR PROCESSING URANIUM ORES The following States are Members of the International Atomic Energy Agency: AFGHANISTAN HOLY SEE PHILIPPINES ALBANIA HUNGARY POLAND ALGERIA ICELAND PORTUGAL ARGENTINA INDIA QATAR AUSTRALIA INDONESIA ROMANIA AUSTRIA IRAN SAUDI ARABIA BANGLADESH IRAQ SENEGAL BELGIUM IRELAND SIERRA LEONE BOLIVIA ISRAEL SINGAPORE BRAZIL ITALY SOUTH AFRICA BULGARIA IVORY COAST SPAIN BURMA JAMAICA SRI LANKA BYELORUSSIAN SOVIET JAPAN SUDAN SOCIALIST REPUBLIC JORDAN SWEDEN CANADA KENYA SWITZERLAND CHILE KOREA, REPUBLIC OF SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC COLOMBIA KUWAIT THAILAND COSTA RICA LEBANON TUNISIA CUBA LIBERIA TURKEY CYPRUS LIBYAN ARAB JAMAHIRIYA UGANDA CZECHOSLOVAKIA LIECHTENSTEIN UKRAINIAN SOVIET SOCIALIST DEMOCRATIC KAMPUCHEA LUXEMBOURG REPUBLIC DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE'S MADAGASCAR UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF KOREA MALAYSIA REPUBLICS DENMARK MALI UNITED ARAB EMIRATES DOMINICAN REPUBLIC MAURITIUS UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT ECUADOR MEXICO BRITAIN AND NORTHERN EGYPT MONACO IRELAND EL SALVADOR MONGOLIA UNITED REPUBLIC OF ETHIOPIA MOROCCO CAMEROON FINLAND NETHERLANDS UNITED REPUBLIC OF FRANCE NEW ZEALAND TANZANIA GABON NICARAGUA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA GERMAN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC NIGER URUGUAY GERMANY, FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA VENEZUELA GHANA NORWAY VIET NAM GREECE PAKISTAN YUGOSLAVIA GUATEMALA PANAMA ZAIRE HAITI PARAGUAY ZAMBIA PERU The Agency's Statute was approved on 23 October 1956 by the Conference on the Statute of the IAEA held at United Nations Headquarters, New York; it entered into force on 29 July 1957. -

A Review of Flotation Separation of Mg Carbonates (Dolomite and Magnesite)

minerals Review A Review of Flotation Separation of Mg Carbonates (Dolomite and Magnesite) Darius G. Wonyen 1,†, Varney Kromah 1,†, Borbor Gibson 1,† ID , Solomon Nah 1,† and Saeed Chehreh Chelgani 1,2,* ID 1 Department of Geology and Mining Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University of Liberia, P.O. Box 9020 Monrovia, Liberia; [email protected] (D.G.W.); [email protected] (Y.K.); [email protected] (B.G.); [email protected] (S.N.) 2 Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-41-6830-9356 † These authors contributed equally to the study. Received: 24 July 2018; Accepted: 13 August 2018; Published: 15 August 2018 Abstract: It is well documented that flotation has high economic viability for the beneficiation of valuable minerals when their main ore bodies contain magnesium (Mg) carbonates such as dolomite and magnesite. Flotation separation of Mg carbonates from their associated valuable minerals (AVMs) presents several challenges, and Mg carbonates have high levels of adverse effects on separation efficiency. These complexities can be attributed to various reasons: Mg carbonates are naturally hydrophilic, soluble, and exhibit similar surface characteristics as their AVMs. This study presents a compilation of various parameters, including zeta potential, pH, particle size, reagents (collectors, depressant, and modifiers), and bio-flotation, which were examined in several investigations into separating Mg carbonates from their AVMs by froth flotation. Keywords: dolomite; magnesite; flotation; bio-flotation 1. Introduction Magnesium (Mg) carbonates (salt-type minerals) are typical gangue phases associated with several valuable minerals, and have complicated processing [1,2]. -

Calcination) 2

Thermal Treatment of Catalysts Modern Methods in Heterogeneous Catalysis Research Friederike C. Jentoft, October 31, 2003 Outline 1. Terminology (calcination) 2. Sample vs. oven set temperature 3. Self-generated atmosphere & self-steaming of zeolites 4. Combustion 5. Glow phenomenon & zirconia catalysts 6. Crystallization 7. Loss of surface area 8. Effect of additives 9. Solid-solid wetting 10.Reductive treatments & SMSI Steps of Catalyst Preparation v IUPAC defines 3 steps of catalyst preparation 1. Preparation of primary solid, associating all the useful compounds 2. Processing of that primary solid to obtain the catalyst precursor for example by heat treatment 3. Activation of the precursor to give the active catalyst (reduction to metal, formation of sulfides, deammoniation of zeolites) Heat Treatment of Intermediate Solids or Precursors v drying v thermal decomposition of salts (nitrates, ammonium salts) v calcination v product is a "reasonably inert solid" which can be stored easily Annealing v in a general meaning: a heating of a material over a long time span; strain and cracks in a crystalline solid can be removed Origin of the Term "Calcination" v latin "calx" = playstone limestone, (greek chálix) v burning of calcium carbonate (limestone) to calcium oxide (quicklime) -1 CaCO3 → CaO + CO2 ΔH(900°C)=3010 kJ mol v used to construct Giza pyramids (ca. 2800 A.C.), burning of limestone ("Kalkbrennen") mentioned by Cato 184 A.C. v performed in kilns (ovens) at 900°C v addition of air to sustain combustion + cool product Examples for -

Experiments with the Ammonium Amalgam

Experiments with the Ammonium Amalgam. [from THE AM. JOURNAL OF SCIENCE, VOL. XL, SEPT., 1865.] EXPERIMENTS WITH THE AMMONIUM AMALGAM, BY CHARLES M. WETHERILL, Ph.D., M.D. The existence of the hypothetical radical NH 4 depends less upon the characteristics of its so-called amalgam than! upon the parallelism of its salts with those of the alkalies. If, from these analogies, we accept the metallic nature of ammonium, it will be difficult to avoid assigning a similar character to the rad- icals of all of the organic bases; and especially to those which, like the compound /ammonias, have an alkaline reaction and possess physical and chemical properties so like ammonia. If such be the inference, we must admit numerous compound metals exists only in certain of , which states of combination their elements. The assumption of the elementary nature of a metal is destroyed and the ideas of the alchemists are re- ; a may vived for if NH 4 be metal and NH 3 be not one, why not other metals, esteemed elements, be also compounds. In examining the so-called ammonium amalgam one is inter- ested at the great resemblance which it bears to the amalgams proper in its physical properties. The mercury has lost its flu- idity or mobility, and, at the same time, its relations of cohesion and adhesion are very sensibly altered. It no longer coheres powerfully; but adheres to, or Wets, platinum, iron and other metals, like the potassium or sodium amalgam. When left to C. M. Wetherill—Experiments with Ammonium Amalgam. 3 itself, the swollen mass shrinks, and gradually resolves itself into NH 3(NH 0) H and Hg, because (as it is usually explained) NH 4 has 4 a great tendency to fall apart into NH 3 and H. -

Curbing Illicit Mercury and Gold Flows in West Africa: Options for a Regional Approach

Curbing Illicit Mercury and Gold Flows in West Africa: Options for a Regional Approach i INCLUSIVE AND SUSTAINABLE INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ii Curbing Illicit Mercury and Gold Flows in West Africa: Options for a Regional Approach iii November 2018 iv © UNIDO 2018. All rights reserved. This document has been produced without formal United Nations editing. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or its economic system or degree of development. Designations such as ‘developed’, ‘industrialized’ or ‘developing’ are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgement about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. Mention of firm names or commercial products does not constitute an endorsement by UNIDO. Unless otherwise men- tioned, all references to sums of money are given in United States dollars. References to ‘tons’ are to metric tons, unless otherwise stated. All photos © UNIDO unless otherwise stated. Cover photo by Sadibou Sylla Acknowledgements This report was authored by Marcena Hunter of the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. The report is part of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) project, funded by the Government of Switzerland, to assist the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in its early implementation of the Minamata Convention. More information about the Minamata Convention and UNIDO’s work can be found on UNIDO’s website <https://www.unido.org/mercury> or by emailing Gabriela Eigenmann at [email protected]. -

Suppression Mechanisms of Alkali Metal Compounds

SUPPRESSION MECHANISMS OF ALKALI METAL COMPOUNDS Bradley A. Williams and James W. Fleming Chemistry Division, Code 61x5 US Naval Research Lnhoratory Washington, DC 20375-5342, USA INTRODUCTION Alkali metal compounds, particularly those of sodium and potassium, are widely used as fire suppressants. Of particular note is that small NuHCOi particles have been found to be 2-4 times more effective by mass than Halon 1301 in extinguishing both eountertlow flames [ I] and cup- burner flames [?]. Furthermore, studies in our laboratory have found that potassium bicarbonate is some 2.5 times more efficient by weight at suppression than sodium bicarhonatc. The primary limitation associated with the use of alkali metal compounds is dispersal. since all known compounds have very low volatility and must he delivered to the fire either as powders or in (usually aqueous) solution. Although powders based on alkali metals have been used for many years, their mode of effective- ness has not generally been agreed upon. Thermal effects [3],namely, the vaporization of the particles as well as radiative energy transfer out of the flame. and both homogeneous (gas phase) and heterogeneous (surface) chemistry have been postulated as mechanisms by which alkali metals suppress fires [4]. Complicating these issues is the fact that for powders, particle size and morphology have been found to affect the suppression properties significantly [I]. In addition to sodium and potassium, other alkali metals have been studied, albeit to a consider- ably lesser extent. The general finding is that the suppression effectiveness increases with atomic weight: potassium is more effective than sodium, which is in turn more effective than lithium [4]. -

HISTORY of LEAD POISONING in the WORLD Dr. Herbert L. Needleman Introduction the Center for Disease Control Classified the Cause

HISTORY OF LEAD POISONING IN THE WORLD Dr. Herbert L. Needleman Introduction The Center for Disease Control classified the causes of disease and death as follows: 50 % due to unhealthy life styles 25 % due to environment 25% due to innate biology and 25% due to inadequate health care. Lead poisoning is an environmental disease, but it is also a disease of life style. Lead is one of the best-studied toxic substances, and as a result we know more about the adverse health effects of lead than virtually any other chemical. The health problems caused by lead have been well documented over a wide range of exposures on every continent. The advancements in technology have made it possible to research lead exposure down to very low levels approaching the limits of detection. We clearly know how it gets into the body and the harm it causes once it is ingested, and most importantly, how to prevent it! Using advanced technology, we can trace the evolution of lead into our environment and discover the health damage resulting from its exposure. Early History Lead is a normal constituent of the earth’s crust, with trace amounts found naturally in soil, plants, and water. If left undisturbed, lead is practically immobile. However, once mined and transformed into man-made products, which are dispersed throughout the environment, lead becomes highly toxic. Solely as a result of man’s actions, lead has become the most widely scattered toxic metal in the world. Unfortunately for people, lead has a long environmental persistence and never looses its toxic potential, if ingested. -

Atomic Order in Non-Equilibrium Silicon-Germanium-Tin Semiconductors

Atomic Order in Non-Equilibrium Silicon-Germanium-Tin Semiconductors S. Mukherjee1, N. Kodali1, D. Isheim2, S. Wirths3, J. M. Hartmann4, D. Buca3, D. N. Seidman2, and O. Moutanabbir1,* 1 Department of Engineering Physics, École Polytechnique de Montréal, Montréal, C. P. 6079, Succ. Centre-Ville, Montréal, Québec H3C 3A7, Canada. 2 Department of Materials Science and Engineering and Northwestern University Center for Atom-Probe Tomography, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208-3108, USA. 3 Peter Grünberg Institute 9 and JARA - FIT, Forschungszentrum Juelich, Juelich 52425, Germany. 4 CEA, LETI, Minatec Campus, 17 rue des Martyrs, Grenoble 38054, France. The precise knowledge of the atomic order in monocrystalline alloys is fundamental to understand and predict their physical properties. With this perspective, we utilized laser-assisted atom probe tomography to investigate the three-dimensional distribution of atoms in non-equilibrium epitaxial Sn-rich group IV SiGeSn ternary semiconductors. Different atom probe statistical analysis tools including frequency distribution analysis, partial radial distribution functions, and nearest neighbor analysis were employed in order to evaluate and compare the behavior of the three elements to their spatial distributions in an ideal solid solution. This atomistic-level analysis provided clear evidence of an unexpected repulsive interaction between Sn and Si leading to the deviation of Si atoms from the theoretical random distribution. This departure from an ideal solid solution is supported by first principal calculations and attributed to the tendency of the system to reduce its mixing enthalpy throughout the layer-by-layer growth process. PACS: 68.35 bd, 38.35 bg, 34.20 Gj, 68.35 Dv 1 The assumption that the arrangement of atoms within the crystal lattice is perfectly random is a broadly used approximation to establish the physical properties of semiconductor alloys. -

Growth and Characterization of Silicon-Germanium-Tin Semiconductors for Future Nanophotonics Devices" (2018)

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 12-2018 Growth and Characterization of Silicon- Germanium-Tin Semiconductors for Future Nanophotonics Devices Bader Saad Alharthi University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Electromagnetics and Photonics Commons, and the Semiconductor and Optical Materials Commons Recommended Citation Alharthi, Bader Saad, "Growth and Characterization of Silicon-Germanium-Tin Semiconductors for Future Nanophotonics Devices" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 3012. https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/3012 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Growth and Characterization of Silicon-Germanium-Tin Semiconductors for Future Nanophotonics Devices A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Engineering with a concentration in Electrical Engineering by Bader Saad Alharthi King Saud University Bachelor of Science in Physics, 2003 King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals Master of Science in Physics, 2009 University of Arkansas Master of Science in Electrical Engineering, 2018 December 2018 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. Hameed A. Naseem, Ph.D. Shui-Qing (Fisher) Yu, Ph.D. Dissertation Director Dissertation Co-Director Simon Ang, Ph.D. Zhong Chen, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member Hugh Churchill, Ph.D. Committee Member Abstract The bright future of silicon (Si) photonics has attracted research interest worldwide. The ultimate goal of this growing field is to develop a group IV based Si foundries that integrate Si-photonics with the current complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS) on a single chip for mid- infrared optoelectronics and high speed devices. -

Mercury--Quicksilver

scueu« No. 12 Mineral Technology Series No 6 University of Arizona Bulletin Mercury---Quicksilver By P. E. JOSEPH SECOND ISSUE NOVEMBER, 1916. Entered as second class matter November 2:1, 191~, at the postoftice at Tucson, Arizona. under the Act ot August 24, 1912. Issued weekb". September to Ya)·. PUBLISHED BY THE University of Arizona Bureau of Mines CHARLES F. WILLIS, Director TUCSON, ARIZONA 1916-17 BIBLIOGRAPHY Bancroft, Howland. Notes on the occurrence of cinnabar in central western Arizona. U. S. G. S. Bull. 430, pp. 151-153, 1910. Becker, G. F. Geology of- the quicksilver deposits of the Pacific slope, with atlas. Mon. 13, p. 486, 1888. Only the atlas in stock. Quicksilver Ore Deposits; Mineral Resources U. S. for 1892, pp. 139-168, 1893. Christy, S. B. Quicksilver reduction at New Almaden, Cal. Min- eral Resources U. S. for 1883-1884, pp. 603-636, 1885. Hillebrand, W. F., and Schaller, W. T. Mercury miner-als from Terlingua, Tex. U. S. G. S. Bull. 405, pp. 174, 1909. McCaskey, H. D. Quicksilver in 1912; Mineral Resources U. S. for 1912, Pt. 1, pp. 931-948, 1913. Quicksilver in 1913-Production and Resources; Mineral Resources U. S. for 1913, Pt. 1, pp. 197-212, 1914. Melville, W. H., and Lindgren, Waldemar. Contributions to the mineralogy of the Pacific coast. U. S. G. S. Bull. 61, 30 pp., 1890. Parker, E. W. Quicksilver; Twenty-first Ann. Rept. U. S. G. S., Pt. 6, pp. 273-283, 1901. University of Arizona Bulletin BULLETIN No. 12 SECOND ISSUE, NOVEMBER, 1916 MERCURY-QUICKSILVER By P. -

Principles of Extractive Metallurgy Lectures Note

PRINCIPLES OF EXTRACTIVE METALLURGY B.TECH, 3RD SEMESTER LECTURES NOTE BY SAGAR NAYAK DR. KALI CHARAN SABAT DEPARTMENT OF METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS ENGINEERING PARALA MAHARAJA ENGINEERING COLLEGE, BERHAMPUR DISCLAIMER This document does not claim any originality and cannot be used as a substitute for prescribed textbooks. The information presented here is merely a collection by the author for their respective teaching assignments as an additional tool for the teaching-learning process. Various sources as mentioned at the reference of the document as well as freely available material from internet were consulted for preparing this document. The ownership of the information lies with the respective author or institutions. Further, this document is not intended to be used for commercial purpose and the faculty is not accountable for any issues, legal or otherwise, arising out of use of this document. The committee faculty members make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this document and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. BPUT SYLLABUS PRINCIPLES OF EXTRACTIVE METALLURGY (3-1-0) MODULE I (14 HOURS) Unit processes in Pyro metallurgy: Calcination and roasting, sintering, smelting, converting, reduction, smelting-reduction, Metallothermic and hydrogen reduction; distillation and other physical and chemical refining methods: Fire refining, Zone refining, Liquation and Cupellation. Small problems related to pyro metallurgy. MODULE II (14 HOURS) Unit processes in Hydrometallurgy: Leaching practice: In situ leaching, Dump and heap leaching, Percolation leaching, Agitation leaching, Purification of leach liquor, Kinetics of Leaching; Bio- leaching: Recovery of metals from Leach liquor by Solvent Extraction, Ion exchange , Precipitation and Cementation process. -

Sodium Aluminium Silicate (Tentative)

SODIUM ALUMINIUM SILICATE (TENTATIVE) th Prepared at the 80 JECFA and published in FAO JECFA Monographs 17 (2015), superseding tentative specifications prepared at the 77th JECFA (2013) and published in FAO JECFA Monographs 14 (2013). An ADI 'not specified' for silicon dioxide and certain silicates was established at the 29th JECFA (1985). A PTWI of 2 mg/kg bw for total aluminium was established at the 74th JECFA (2011). The PTWI applies to all aluminium compounds in food, including food additives. Information required: Functional uses other than anticaking agent, if any, and information on the types of products in which it is used and the use levels in these products Data on solubility using the procedure documented in the “Compendium of Food Additives Specifications, Vol. 4, Analytical methods” Data on the impurities soluble in 0.5 M hydrochloric acid, from a minimum of five batches. If a different extraction and determination method is used, provide data along with details of method and QC data. Suitability of the analytical method for the determination of aluminium, silicon and sodium using the proposed “Method of assay” along with data, from a minimum of five batches, using the proposed method. If a different method is used, provide data along with details of the method and QC data. SYNONYMS Sodium silicoaluminate; sodium aluminosilicate; aluminium sodium silicate; silicic acid, aluminium sodium salt; INS No. 554 DEFINITION Sodium aluminium silicate is a series of amorphous hydrated sodium aluminium silicates with varying proportions of Na2O, Al2O3 and SiO2. It is manufactured by, precipitation process, reacting aluminium sulphate and sodium silicate.