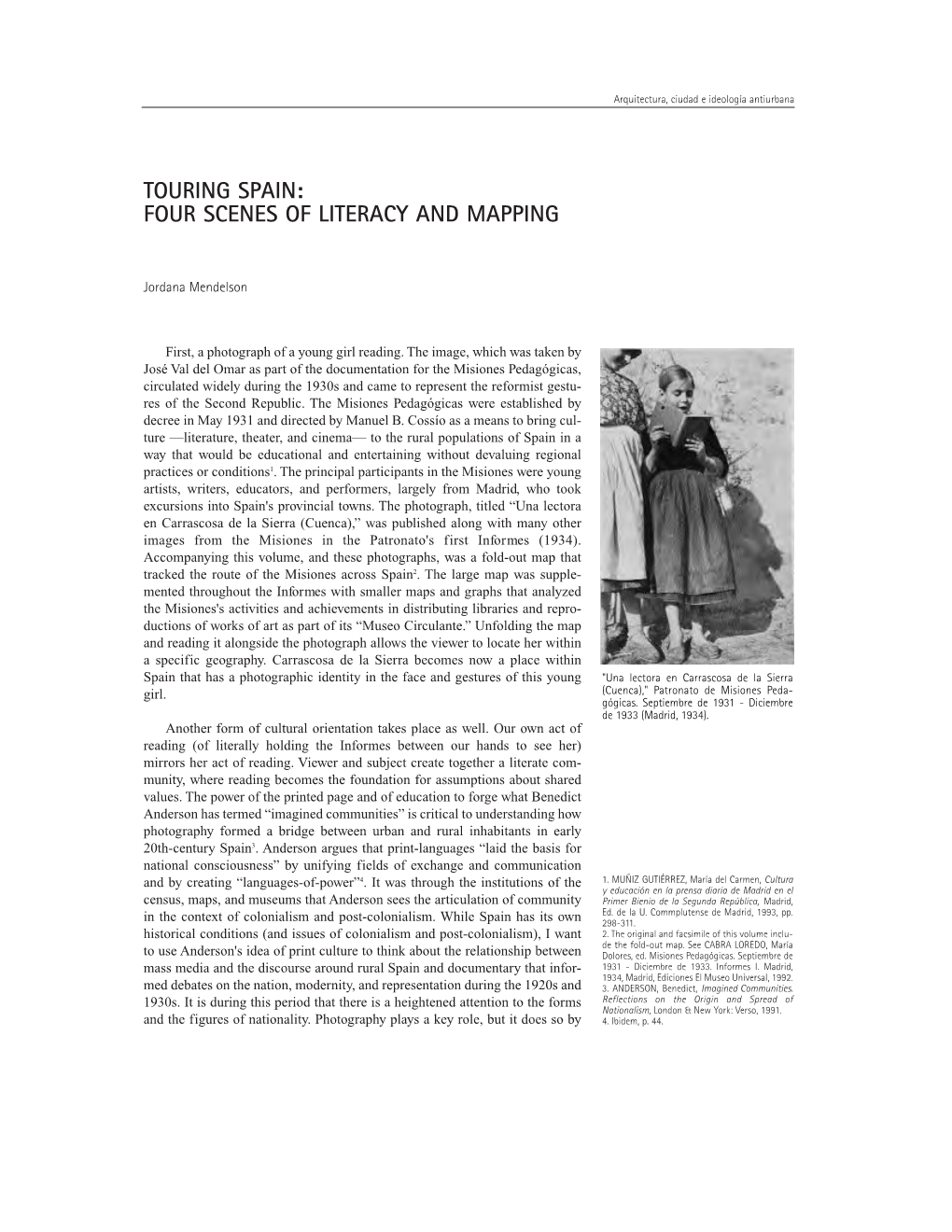

Four Scenes of Literacy and Mapping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memoria Avance

DOCUMENTO DE AVANCE DEL PLAN GENERAL MUNICIPAL AHIGAL MEMORIA ANTONINO ANTEQUERA-ARQUITECTO REDACTOR PLAN GENERAL MUNICIPAL AHIGAL MEMORIA INFORMATIVA MEMORIA INFORMATIVA ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 TÍTULO 1: EL MEDIO FÍSICO ................................................................................................................................................................. 5 CAPÍTULO 1: ESTRUCTURA FISICO AMBIENTAL. ............................................................................................................................... 5 Artículo 1.1.1.- Encuadre Geográfico ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Artículo 1.1.2.- Resumen Histórico .................................................................................................................................................... 6 Artículo 1.1.3.- Relaciones Supramunicipales ................................................................................................................................ 6 Artículo 1.1.4.- Valoración del Territorio .......................................................................................................................................... 7 CAPÍTULO 2: CLIMA ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

Estudio De Impacto Ambiental

ESTUDIO DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL MODIFICACIÓN PROYECTO DELIMITACIÓN DE SUELO URBANO DE LADRILLAR Excmo. Ayuntamiento de Ladrillar Mª del Mar Marcos Martín, Licenciada en Ciencias Ambientales - Agosto de 2013 - INDICE 1. Introducción .............................................................................................- 5 - 1.1. Antecedentes ....................................................................................- 5 - 1.2. Objeto del proyecto ...........................................................................- 6 - 2. Marco Normativo .....................................................................................- 8 - 2.1. Legislación específica de EIA............................................................- 8 - 2.2. Legislación Sectorial .........................................................................- 9 - 3. Descripción sintética de la modificación ................................................- 12 - 3.1. Tabla resumen ................................................................................- 12 - 3.2. Justificación.....................................................................................- 13 - 3.3. Relación con otros planes de ordenación territorial.........................- 14 - 4. Inventario Ambiental del ámbito territorial del proyecto .........................- 15 - 4.1. Descripción general del medio ........................................................- 15 - 4.2. Clima ...............................................................................................- 16 -

EXTREMADURA RURAL | Mapa Turístico

EXTREMADURA RURAL MAPA TURÍSTICO GRUPOS DE ACCIÓN LOCAL redex.org/turismo Lácara Las Hurdes Campo Arañuelo Valle del Ambroz ADECOM LÁCARA ADIC - HURDES ARJABOR DIVA Monfragüe y su Entorno Miajadas - Trujillo Campiña Sur Sierra Grande - Tierra de Barros ADEME ADICOMT CEDER CAMPIÑA SUR FEDESIBA Olivenza La Vera Trasierra - Tierras de Granadilla Sierra de San Pedro - Los Baldíos ADERCO ADICOVER CEDER CÁPARRA SIERRA DE SAN PEDRO - LOS BALDÍOS Sierra Suroeste Sierra de Gata Tentudía Valle del Jerte ADERSUR ADISGATA CEDECO TENTUDÍA SOPRODEVAJE Valle del Alagón Sierra de Montánchez y Tamuja La Serena Tajo-Salor-Almonte ADESVAL ADISMONTA CEDER LA SERENA TAGUS Vegas Altas del Guadiana Villuercas Ibores Jara La Siberia Zafra - Río Bodión ADEVAG APRODERVI CEDER LA SIBERIA CEDER ZAFRA - RÍO BODIÓN MAPA TURÍSTICO ¿QUÉ ES REDEX? EN ESTE DESPLEGABLE EXTREMADURA RURAL Te presentamos información útil y práctica para La Red Extremeña de Desarrollo Rural, REDEX, es una descubrir la Extremadura innita. entidad sin ánimo de lucro que aglutina a los 24 Contempla los diversos colores del paisaje, pasea Grupos de Acción Local extremeños y promueve la por las extensas dehesas extremeñas, entra en sus consecución de dos grandes objetivos: museos y centros de interpretación, practica el @redextremadura pedaleo BTT por sus múltiples senderos, iníciate en el avistamiento de aves, disfruta de una gastronomía redex.org @redextremenadesarrollorural 1 Representar a sus asociados ante las dife- monumental o relájate en alguno de los balnearios @extremadurarural rentes administraciones implicadas en la gestión que riegan la antigua Vía de la Plata. de los diferentes programas que los Grupos de Son solo algunas propuestas en esta Extremadura Acción Local están ejecutando en Extremadura y innita. -

Candidatura Proder Ii De La Comarca De Las Hurdes

C omarca de Las Hurdes. A NEXO 3. CANDIDATURA PRODER II DE LA COMARCA DE LAS HURDES Documento Resumen CEDER DE ADIC-HURDES C EDER DE ADIC-HURDES 1 C omarca de Las Hurdes. A NEXO 3. Descripción del Territorio 1. Denominación de la comarca.:la Comarca de Las Hurdes 2. Relación de términos municipales y entidades locales incluídas. superficie y población de cada una de ellas. Municipio Unidad Poblacional Población total Caminomorisco 000300 CAMBRONCINO 230 Caminomorisco 000200 CAMBRON 32 Caminomorisco 000400 CAMINOMORISCO 776 Caminomorisco 000500 DEHESILLA 23 Caminomorisco 000600 HUERTA 55 Caminomorisco 000100 ARROLOBOS 131 Caminomorisco 000700 RIOMALO DE ABAJO 45 Casar de Palomero 000200 CASAR DE PALOMERO 765 Casar de Palomero 000100 AZABAL 308 Casar de Palomero 000300 PEDRO-MUÑOZ 76 Casar de Palomero 000400 RIVERA OVEJA 98 Casares de las Hurdes 000100 CARABUSINO 117 Casares de las Hurdes 000200 CASARRUBIA 71 Casares de las Hurdes 000300 CASARES DE LAS HURDES 124 Casares de las Hurdes 000400 HERAS 35 Casares de las Hurdes 000500 HUETRE 64 Casares de las Hurdes 000600 ROBLEDO 171 Ladrillar 000300 MESTAS (LAS) 64 Ladrillar 000400 RIOMALO DE ARRIBA 16 Ladrillar 000100 CABEZO 54 Ladrillar 000200 LADRILLAR 115 Nuñomoral 000800 RUBIACO 92 Nuñomoral 000700 NUÑOMORAL 326 Nuñomoral 000600 MARTILANDRAN 160 Nuñomoral 000300 CEREZAL 141 Nuñomoral 000200 ASEGUR 126 Nuñomoral 000100 ACEITUNILLA 101 Nuñomoral 000900 VEGAS DE CORIA 234 Nuñomoral 000400 FRAGOSA 186 Nuñomoral 000500 GASCO (EL) 157 Pinofranqueado 001000 ROBLEDO 69 Pinofranqueado 000100 ALDEHUELA 38 Pinofranqueado 000200 AVELLANAR 17 Pinofranqueado 000300 CASTILLO 96 Pinofranqueado 000600 MESEGAL 66 Pinofranqueado 000700 MUELA 77 Pinofranqueado 000900 PINOFRANQUEADO 929 Pinofranqueado 001100 SAUCEDA 99 Pinofranqueado 000800 OVEJUELA 117 C EDER DE ADIC-HURDES 2 C omarca de Las Hurdes. -

8. Espacios Protegidos Y Conservación De La Naturaleza En Extremadura Desde Una Perspectiva Histórica Y Ecológica

8. ESPACIOS PROTEGIDOS Y CONSERVACIÓN DE LA NATURALEZA EN EXTREMADURA DESDE UNA PERSPECTIVA HISTÓRICA Y ECOLÓGICA José María Corrales Vázquez 1. INTRODUCCIÓN Ha pasado ya casi un siglo y medio desde que Yellowstone fuera declarado como el primer Parque Nacional del Planeta. El camino de protección de espacios naturales entonces iniciado se ha extendido por la casi totalidad de los países del mundo, que reconocen así que la naturaleza, en sus expresiones más genuinas, constituye el patrimonio común de sus ciudadanos y de toda la humanidad. En su origen, la creación de los parques nacionales, rápidamente deriva a dos concepciones distintas: la europea de protección a ultranza, intentando la previa desapari- ción de toda influencia antrópica, y la americana de mayor satisfacción estética, y con aparente finalidad educativa, conducente al espectáculo y al solaz turístico. España no ha sido una excepción en el proceso de declaración de espacios protegidos. Antes bien, nuestro país puede considerarse pionero en esta línea y, así, nuestro ordenamiento jurídico concede la figura de Parque Nacional desde el año 1916. Las inquietudes de una serie de ilustrados encabezados por Beraldo Quirós, Marqués de Villaviciosa y el extremeño Eduardo Hernández Pacheco tuvieron fruto en el año 1918, con la constitución de los Parques Nacionales de la Montaña de Covadonga y de Ordesa. El ejemplo de España fue seguido por otros muchos países y en la actualidad, la mayor parte de los Estados y muchas comunidades autónomas, con independencia de su situación geo- gráfica o nivel de desarrollo, cuentan con una red propia de espacios naturales protegidos y una legislación que los proteje. -

The Distribution of Rural Accommodation in Extremadura, Spain-Between the Randomness and the Suitability Achieved by Means of Regression Models (OLS Vs

sustainability Article The Distribution of Rural Accommodation in Extremadura, Spain-between the Randomness and the Suitability Achieved by Means of Regression Models (OLS vs. GWR) José-Manuel Sánchez-Martín 1,* , José-Luis Gurría-Gascón 2 and Juan-Ignacio Rengifo-Gallego 2 1 Faculty of Business, Finance and Tourism, University of Extremadura, 10071 Cáceres, Spain 2 Faculty of Letters, University of Extremadura, 10071 Cáceres, Spain; [email protected] (J.-L.G.-G.); [email protected] (J.-I.R.-G.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 21 May 2020; Accepted: 8 June 2020; Published: 10 June 2020 Abstract: There are multiple types of regression, the essential task of which is the obtaining of models which, starting from a set of regressive values, are capable of finding explanations for the variability of a dependent. However, in many cases, the territorial criterion is not considered to be a noteworthy factor of analysis, owing to which this deficiency has encouraged the arising of spatial statistics. Nevertheless, given the variety of regressions, it is not clear which can best be adapted to the analysis of tourism. In this sector, when the supply of accommodation is analysed, it is understood that it must be strongly related to the presence of resources, owing to which it has been taken as an example of an application between two differentiated regression techniques: ordinary least squares (OLS) and geographically weighted regression (GWR), with the objective of determining which of the two is best adapted to this type of analysis. The model has been drawn up based on various methods, although it has been shown that it is more efficient to resort to the declared preferences of the rural tourist, with the starting point being a survey made of the tourists. -

Directorio 2019 Servicios Sociales De Atención Social Básica (Ssasb) De La Comunidad Autónoma De Extremadura

DIRECTORIO 2019 SERVICIOS SOCIALES DE ATENCIÓN SOCIAL BÁSICA (SSASB) DE LA COMUNIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE EXTREMADURA (modificado y actualizado a 29/03/2019) ∗ RESOLUCIÓN de 19 de marzo de 2019, de la Dirección General de Políticas Sociales e Infancia y Familia, por la que se modifica el número de profesionales para la prestación de información, valoración y orientación reconocidos [DOE, núm. 246, 29 de marzo de 2019]. ∗ RESOLUCIÓN de 5 de diciembre de 2018, de la Dirección General de Políticas Sociales e Infancia y Familia, por la que se modifica la organización de los Servicios Sociales de Atención Social Básica de la Comunidad Autónoma de Extremadura [DOE, núm. 246, 20 de diciembre de 2018]. ∗ Las últimas cifras oficiales de población son las resultantes de la revisión del Padrón municipal a 1 de enero de 2018, Real Decreto 1458/2018, de 14 de diciembre, por el que se declaran oficiales las cifras de población resultantes de la revisión del Padrón municipal referidas al 1 de enero de 2018; BOE núm. 314, de 29 de diciembre de 2018. 1 ÍNDICE Directorio de los Servicios Sociales de Atención Social Básica ………………. 4 de La Comunidad Autónoma de Extremadura 001 MANCOMUNIDAD INTERMUNICIPAL …………………………….…. 4 DE LA VERA 002 MANCOMUNIDAD DE MUNICIPIOS …………………………….…. 5 “TAJO-SALOR” 003 MANCOMUNIDAD DE MUNICIPIOS …………………………….…. 6 “SIBERIA” 004 MANCOMUNIDAD INTEGRAL DE …………………………….…. 7 SERVICIOS "CÍJARA" 005 VILLAFRANCA DE LOS BARROS …………………………….…. 8 006 FUENTE DE CANTOS …………………………….…. 9 007 LOS IBORES …………………………….…. 10 008 TRUJILLO …………………………….…. 11 009 CAMPANARIO …………………………….…. 12 010 MONTIJO …………………………….…. 13 011 MANCOMUNIDAD INTEGRAL DE …………………………….…. 14 MUNICIPIOS "CAMPO ARAÑUELO" 012 MANCOMUNIDAD INTEGRAL DE …………………………….…. 15 MUNICIPIOS "VALLE DEL AMBROZ" 013 MANCOMUNIDAD INTEGRAL “SIERRA …………………………….…. -

Guide to the Autonomia of Extremadura

Spain Badajoz Cáceres Extremadura Contents Getting to Know Extremadura 1 A Tour of its Cities Cáceres 8 Plasencia 10 Badajoz 12 Mérida 14 Travel Routes through Extremadura The Three Valleys 16 United Los Ibores, Guadalupe Kingdom and Las Villuecas 19 Dublin Sierra de Gata and Las Hurdes 21 Ireland London The Route of the Conquistadors 23 La Raya 24 Through Lands of Wine Paris and Artisans 27 La Serena, La Siberia and their Reservoirs 29 France The Silver Route 31 Leisure and Events 33 Cantabrian Sea Useful Information 36 Spain Portugal Madrid Cáceres Lisbon Badajoz Mediterranean Extremadura Sea Melilla Ceuta Rabat Morocco Atlantic Ocean Canary Islands CIUDAD RODRIGO 8 km SALAMANCA 36 km AVILA 9 km SALAMANCA MADRID 72 km MADRID 74 km SONSECA 49 km Casares Cepeda ÁVILA de las Hurdes El Ladrillar Las Mestas Piedrahita Nuñomoral Vegas de Béjar Burgohondo San Martín Sabugal 1367 Coria Riomalo de Valdeiglesias Robledillo Jañona Descargamaría Pinofranqueado Baños de Montemayor El Barco de Avila Sotillo de S.Martín Aldeanueva Valverde Casar de Hervás la Adrada Fundão de Trevejo Gata Marchagaz Palomero del Camino del Fresno Cadalso Arenas de Penamacor Acebo Emb. de Tornavacas Eljas Torre de Palomero Gabriel y Galán Cabezuela Jerte San Pedro Hoyos D. Miguel Trevejo Pozuelos Ahigal del Valle Jarandilla Villanueva 630 El Torno de Zarzón Aldeanueva de la Vera de la Vera Madrigal Cilleros Emb. de 110 de la Vera Borbollón P Losar Valverde Moraleja Carcaboso Garganta P Piornal Cuacos de Yuste de la Vera Montehermoso la Olla Plasencia Pasarón Jaráiz Las Ventas de la Vera Coria Galisteo de la Vera Talayuela de San Julián Talavera de la Reina Malpartida Navalmoral Zarza la Mirabel de Plasencia Torrejoncillo de la Mata CASTELO BRANCO Mayor T Casatejada OLEDO 33 km L L Ceclavín Oropesa T OLEDO Piedras Acehuche Portezuelo Serradilla Emb. -

Dossier Informativo

DOSSIER INFORMATIVO ÍNDICE Extremadura Rutas a Motor: a tu aire y en la mejor compañía .......................................... 3 Un destino seguro este verano con productos para todos los públicos ............................... 4 Turismo itinerante, una tendencia al alza ......................................................................... 8 Perfil del turista ..................................................................................................................... 8 Campings ............................................................................................................................... 9 12 rutas a motor y 11 carreteras paisajísticas .................................................................. 10 Ruta 1. Plasencia, Valle del Jerte y La Vera ......................................................................... 10 Ruta 2. Valle del Ambroz y Tierras de Granadilla ................................................................ 10 Ruta 3. Sierra de Gata y Las Hurdes .................................................................................... 10 Ruta 4. Reserva de la Biosfera de Monfragüe ..................................................................... 11 Ruta 5. Cáceres, Trujillo y entorno ...................................................................................... 11 Ruta 6. Guadalupe y Geoparque Villuercas-Ibores-Jara ..................................................... 12 Ruta 7. Reserva de la Biosfera Tajo Internacional .............................................................. -

Diablos, Pastores Y De1viografia La Poblacion De Las Hurdes Durante El Antiguo Regimen

Norba 11-12 Revista de Historia. Cáceres, 1991-1992: 231-248. DIABLOS, PASTORES Y DE1VIOGRAFIA LA POBLACION DE LAS HURDES DURANTE EL ANTIGUO REGIMEN JOSE PABLO BLANCO CARRASCO Muy pocas comarcas españolas gozan de un bagaje historiográfico tan fecundo como el que el paso del tiempo ha acumulado en la pequeña y extrema comarca de Las Hurdes. También, y quizá por idénticas razones, es la comarca sobre la que más tópicos se han extendido y propagado desde los años finales del siglo XVI; a pesar de ello, nuestro interés ahora no es hacer catálogo ni de éstos ni de aquél. Una publicación más o menos reciente recoge pormenorizadamente cuanto se ha escrito sobre el origen, las costumbres y los vicios morales de sus pobladores 1 De las ideas preconcebidas que pulularon por los salones decimonónicos de la Sociedad Geográfica Nacional tampoco daré cuenta, ya que, en realidad no queremos justificar la necesidad de este trabajo a partir del confuso concepto de la justicia histórica. Apelar a la verdad está, desde luego, fuera de nuestra intención. Todo es más sencillo. Se trata de aprovechar aquello que nos puede ser de alguna utilidad de todo cuanto se ha dicho para esclarecer uno de los puntos menos conocidos y oscuros de las historia de Las Hurdes: su población y la evolución de su estnictura demográfica a través de más de tres siglos de historia colectiva; en ŭltimo término, la historiografía nos enseria que cada texto está inmerso en su época, y se justifica a través de ella. Pocas veces, además, una realidad ha generado un maniqueísmo tan patente y que se haya transmitido en casi absoluta puridad desde el inicio de la "leyenda negra" que rodea a la comprensión de este territorio; alegoría del mundo desconocido en la época de los descubrimientos, ejemplo de la decadencia del país y de la inocencia del humilde, reflejo grotesco y distorsionado de la España decimonónica y por fin escenario de un sueño surrealista: en cualquier caso punto de comparación y de reflexión. -

Capítulo 4. Síntesis De La Distribución Actual

Síntesis de la distribución actual 1. Introducción 2. Contexto paleo-biogeográfico 2.1. Consideraciones históricas 2.2. Marco biogeográfico 3. Contexto geomorfológico: el relieve 4. Factores generales determinantes de la distribución 4.1. Condicionantes climáticos 4.2. Condicionantes del sustrato 4.3. Condicionantes antrópicos 5. Caracterización general de la vegetación 5.1. Vegetación potencial 5.2. Formaciones leñosas actuales 6. Bosques de frondosas perennifolias Capítulo 4 7. Bosques de frondosas caducifolias 8. Matorrales arborescentes mediterráneos 9. Formaciones riparias SÍNTESIS DE LA DISTRIBUCIÓN ACTUAL 97 1. Introducción donos en el encuadre geográfico de la región y su relieve, que determinan en gran medida su clima y microclimas, El paisaje extremeño está dominado por una extensa respectivamente. Las características del sustrato (roca y penillanura cubierta en gran parte por dehesas. Sin embar- suelo) también son presentadas, sin profundizar más allá de go, si miramos más allá de esta aparente uniformidad geo- los aspectos relevantes que, junto con el clima y los condi- morfológica y vegetal que en ocasiones se le atribuye a cionantes históricos, nos ayudan a explicar la distribución Extremadura, descubriremos que existe una importante actual de los bosques. diversidad de formas vegetales y que éstas se combinan de Se analiza de forma sintética la distribución de los cinco maneras diferentes para constituir lo que denominamos grandes grupos de formaciones leñosas climácicas de comunidades vegetales. La distribución de estas comunida- Extremadura: bosques perennifolios, bosques caducifolios, des no es azarosa, sino que responde fundamentalmente a formaciones de matorrales arborescentes, matorrales orófi- los condicionantes del medio natural, tanto actuales como los y formaciones riparias. -

Geología Y Geodiversidad

32 Geología y geodiversidad 33 a historia de la Tierra comen- zó hace aproximadamente unos 4.550 millones de años, sin em- L bargo, las primeras rocas formadas en Extremadura, a la vista de las modernas dataciones, tendrían una edad de no más de 650 millones de años antes del presente (en adelante M.a.). Los restos fósiles extreme- ños más antiguos que hoy conocemos posible- mente no lleguen a alcanzar los 600 millones de años, perteneciendo al Ediacárico (620-452 M.a.), periodo recientemente aprobado por la “International Comission on Stratigrafy” (ICS) en el Congreso Geológico Internacional de Flo- rencia del 2004. En aquel remoto tiempo gran parte de la región era un medio marino en el que se fueron diversifi cando, a lo largo de todo el Paleozoico, distintas comunidades de orga- nismos, cuyos restos han quedado registrados en los estratos extremeños; ellos, a la manera de un documento escrito, nos hablan de la evo- lución temprana de la vida en nuestra comuni- dad. Hace aproximadamente 326 millones de años, durante el Carbonífero, las fuerzas com- prensivas originadas por el acercamiento del gran supercontinente de Gondwana, en cuyo margen norte se situaba Extremadura, al conti- nente de Euramérica determinaron el cierre del Océano Reico, ocasionando la emersión del área donde hoy se ubica la región extremeña. Al fi nal del Carbonífero e inicio del Pérmico acaecieron los cambios fi siográfi cos más drás- ticos pues, en el lugar donde anteriormente se encontraban medios marinos, se fue perfi lando una elevada cordillera que debió alcanzar su máxima altitud en el Pérmico.