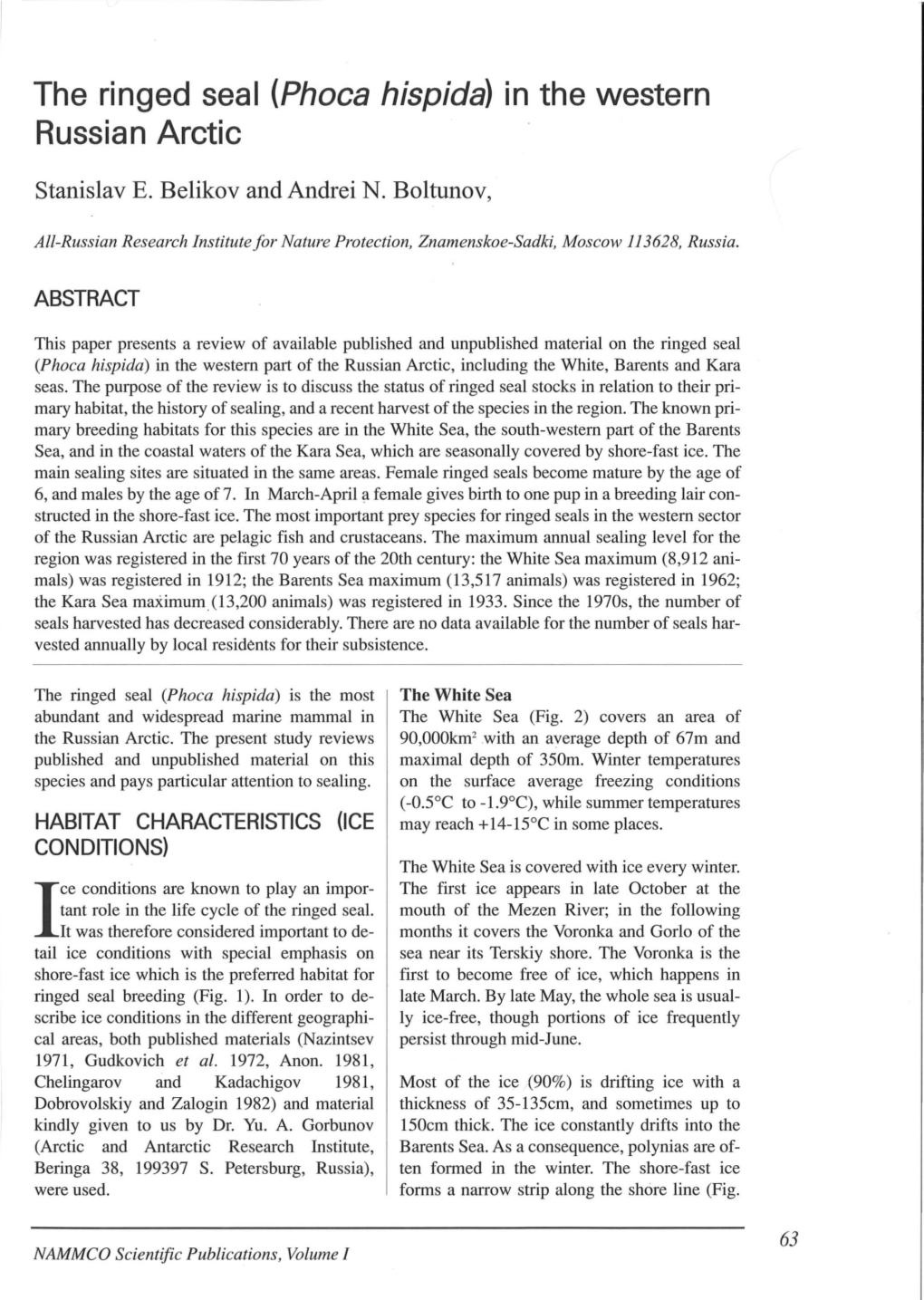

The Ringed Seal (Phoca Hispida) in the Western Russian Arctic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recent Noteworthy Findings of Fungus Gnats from Finland and Northwestern Russia (Diptera: Ditomyiidae, Keroplatidae, Bolitophilidae and Mycetophilidae)

Biodiversity Data Journal 2: e1068 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.2.e1068 Taxonomic paper Recent noteworthy findings of fungus gnats from Finland and northwestern Russia (Diptera: Ditomyiidae, Keroplatidae, Bolitophilidae and Mycetophilidae) Jevgeni Jakovlev†, Jukka Salmela ‡,§, Alexei Polevoi|, Jouni Penttinen ¶, Noora-Annukka Vartija# † Finnish Environment Insitutute, Helsinki, Finland ‡ Metsähallitus (Natural Heritage Services), Rovaniemi, Finland § Zoological Museum, University of Turku, Turku, Finland | Forest Research Institute KarRC RAS, Petrozavodsk, Russia ¶ Metsähallitus (Natural Heritage Services), Jyväskylä, Finland # Toivakka, Myllyntie, Finland Corresponding author: Jukka Salmela ([email protected]) Academic editor: Vladimir Blagoderov Received: 10 Feb 2014 | Accepted: 01 Apr 2014 | Published: 02 Apr 2014 Citation: Jakovlev J, Salmela J, Polevoi A, Penttinen J, Vartija N (2014) Recent noteworthy findings of fungus gnats from Finland and northwestern Russia (Diptera: Ditomyiidae, Keroplatidae, Bolitophilidae and Mycetophilidae). Biodiversity Data Journal 2: e1068. doi: 10.3897/BDJ.2.e1068 Abstract New faunistic data on fungus gnats (Diptera: Sciaroidea excluding Sciaridae) from Finland and NW Russia (Karelia and Murmansk Region) are presented. A total of 64 and 34 species are reported for the first time form Finland and Russian Karelia, respectively. Nine of the species are also new for the European fauna: Mycomya shewelli Väisänen, 1984,M. thula Väisänen, 1984, Acnemia trifida Zaitzev, 1982, Coelosia gracilis Johannsen, 1912, Orfelia krivosheinae Zaitzev, 1994, Mycetophila biformis Maximova, 2002, M. monstera Maximova, 2002, M. uschaica Subbotina & Maximova, 2011 and Trichonta palustris Maximova, 2002. Keywords Sciaroidea, Fennoscandia, faunistics © Jakovlev J et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. -

Transit Passage in the Russian Arctic Straits

International Boundaries Research Unit MARITIME BRIEFING Volume 1 Number 7 Transit Passage in the Russian Arctic Straits William V. Dunlap Maritime Briefing Volume 1 Number 7 ISBN 1-897643-21-7 1996 Transit Passage in the Russian Arctic Straits by William V. Dunlap Edited by Peter Hocknell International Boundaries Research Unit Department of Geography University of Durham South Road Durham DH1 3LE UK Tel: UK + 44 (0) 191 334 1961 Fax: UK +44 (0) 191 334 1962 e-mail: [email protected] www: http://www-ibru.dur.ac.uk Preface The Russian Federation, continuing an initiative begun by the Soviet Union, is attempting to open the Northern Sea Route, the shipping route along the Arctic coast of Siberia from the Norwegian frontier through the Bering Strait, to international commerce. The goal of the effort is eventually to operate the route on a year-round basis, offering it to commercial shippers as an alternative, substantially shorter route from northern Europe to the Pacific Ocean in the hope of raising hard currency in exchange for pilotage, icebreaking, refuelling, and other services. Meanwhile, the international law of the sea has been developing at a rapid pace, creating, among other things, a right of transit passage that allows, subject to specified conditions, the relatively unrestricted passage of all foreign vessels - commercial and military - through straits used for international navigation. In addition, transit passage permits submerged transit by submarines and overflight by aircraft, practices with implications for the national security of states bordering straits. This study summarises the law of the sea as it relates to straits used for international navigation, and then describes 43 significant straits of the Northeast Arctic Passage, identifying the characteristics of each that are relevant to a determination of whether the strait will be subject to the transit-passage regime. -

Personal, Societal, and Ecological Values Of

Study of Plant Species Diversity in the West Siberian Arctic Olga Khitun Olga Rebristaya Abstract—The West Siberian Arctic, due to its history and physi- anywhere; the territory is covered by a thick (up to 300 ography, is characterized by a simple biotope (habitat) structure meters) layer of Quaternary deposits, formed by alternat- and low species richness. By analyzing full vegetative species ing clay, clayey, and sandy layers (Sisko 1977). The study inventories in specific localities, comparisons of floras of different area lies within the zone of continuous permafrost, where biotopes (such as partial floras), and identification of the roles of seasonal freeze-thaw processes and cryogenic natural dis- individual species across the landscape, our research revealed turbances (thermokarst, solifluction, streambank erosion, subzonal changes in the structure of plant species diversity. landslides) occur. Though general taxonomic diversity decreases from the southern The climate is continental and rather severe. The absence hypoarctic tundra to the arctic tundra subzone, the number of of weather stations in the study area forced us to use the species in partial floras does not decrease significantly. There was nearest data to characterize climatic conditions (table 1). an increase in ecological amplitudes (mainly of arctic and arctic/ Average July temperatures range from 11 degrees centi- grade in the south to 4 degrees centigrade in the north. alpine species) in the majority of habitats. The ratio of geographi- Average January temperatures range from minus 25 de- cal groups differs greatly between subzones: hypoarctic and boreal grees centigrade in the south to minus 27 degrees centigrade species prevail in the southern subzone; arctic and arctic/alpine in the north; the average low temperature is minus 29 to species replace them in arctic tundra. -

On the Progress of Implementation of the Russian National AMAP Plan Projects (II Stage) by Roshydromet in 2000

RUSSIAN FEDERAL SERVICE for HYDROMETEOROLOGY and ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING On the progress of implementation of the Russian National AMAP Plan Projects (II stage) by Roshydromet in 2000 2000 2 CONTENT 1. ON THE PROGRESS OF IMPLEMENTATION OF THE RUSSIAN NATIONAL AMAP PLAN PROJECTS (II STAGE) BY ROSHYDROMET IN 2000 ………… 3 1.1. Expedition studies …………………………..……………………………….. 3 1.1.1. The “Arctica 2000” expedition ….………………………………… 3 1.1.2. The expedition at Hydrographical Vessel “Nikolai Kolomeets” 4 1.1.3. The “Karex-Pechora 2000” expedition …………………………. 4 1.1.4. The “Lena-2000” expedition ……………………………..………. 4 1.1.5. The “NAR-2000” expedition ……………………………….……… 5 1.2. Stationary systematic observations of the pollution of atmospheric air and atmospheric precipitation …………………………………………. 9 1.3. Radiation monitoring in the Russian Arctic ………………..…………….. 9 1.4. Conclusion …………………………………………………………………..… 10 2. THE JOINT GEF, AMAP, CIRCUMPOLAR ASSOCIATION OF THE INUITS AND ROSHYDROMET PROJECT "PERSISTENT TOXIC SUBSTANCES (PTS), FOOD SECURITY OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLE OF THE RUSSIAN NORTH"……………………………………………………………………………… 12 On the progress of implementation of the Russian National AMAP Plan Projects (II stage) by Roshydromet in 2000 3 1. ON THE PROGRESS OF IMPLEMENTATION OF THE RUSSIAN NATIONAL AMAP PLAN PROJECTS (II STAGE) BY ROSHYDROMET IN 2000 In 2000 in the framework of the Russian National Plan and special projects, the research institutions under the administration of Roshydromet carried out: · complex studies in seasonal expeditions; · stationary systematic observations of atmospheric air contamination in the largest cities of the Russian Arctic (Murmansk, Monchegorsk, Vorkuta, Nikel, Amderma, Norilsk and Salekhard); · observations of the levels of contaminants over the Roshydromet network points; · complex studies and sampling within the framework of the joint Project PAIPON/AMAP/GEF: Persistent Toxic Substances, Food Security and Indigenous People of the Russian North. -

Chronology of the Key Historical Events on the Eastern Seas of the Russian Arctic (The Laptev Sea, the East Siberian Sea, the Chukchi Sea)

Chronology of the Key Historical Events on the Eastern Seas of the Russian Arctic (the Laptev Sea, the East Siberian Sea, the Chukchi Sea) Seventeenth century 1629 At the Yenisei Voivodes’ House “The Inventory of the Lena, the Great River” was compiled and it reads that “the Lena River flows into the sea with its mouth.” 1633 The armed forces of Yenisei Cossacks, headed by Postnik, Ivanov, Gubar, and M. Stadukhin, arrived at the lower reaches of the Lena River. The Tobolsk Cossack, Ivan Rebrov, was the first to reach the mouth of Lena, departing from Yakutsk. He discovered the Olenekskiy Zaliv. 1638 The first Russian march toward the Pacific Ocean from the upper reaches of the Aldan River with the departure from the Butalskiy stockade fort was headed by Ivan Yuriev Moskvitin, a Cossack from Tomsk. Ivan Rebrov discovered the Yana Bay. He Departed from the Yana River, reached the Indigirka River by sea, and built two stockade forts there. 1641 The Cossack foreman, Mikhail Stadukhin, was sent to the Kolyma River. 1642 The Krasnoyarsk Cossack, Ivan Erastov, went down the Indigirka River up to its mouth and by sea reached the mouth of the Alazeya River, being the first one at this river and the first one to deliver the information about the Chukchi. 1643 Cossacks F. Chukichev, T. Alekseev, I. Erastov, and others accomplished the sea crossing from the mouth of the Alazeya River to the Lena. M. Stadukhin and D. Yarila (Zyryan) arrived at the Kolyma River and founded the Nizhnekolymskiy stockade fort on its bank. -

Poac09-53 Experiences of Russian Arctic Navigation

POAC 09 Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Luleå, Sweden Port and Ocean Engineering under Arctic Conditions June 9-12, 2009 Luleå, Sweden POAC09-53 EXPERIENCES OF RUSSIAN ARCTIC NAVIGATION Nataliya Marchenko 1, 2, 3 1 The University Centre in Svalbard, Longyearbyen, Norway 2 The Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Department of Civil and Transport Engineering, Trondheim, Norway 3 State Oceanographic Institute, Moscow, Russia ABSTRACT Shipping in the Arctic seas has a long history and it’s own features. For a modern development of the operation in the northern seas it is very important to learn from the previous ice pilot experiences. PetroArctic project has gathered the information about Russian activities in the Arctic. First part of the research is a description of the five Russian Arctic Seas from the navigation point of view. Both common and unique features for each of the seas are under consideration. Trends in the development of the ships (materials and means of a stronger hull form) and navigation (preferable routes and time) have been deduced. Appreciable amount of written documentation and interviews with actual persons involved were processed. Information about extreme situations (ice drift and ice jet, icing and hummocking, ridging ice opening and closing) and special weather and ice conditions were collected from the sailors and ice pilots. Items of special interest were connected to the shipwrecks and other accidents. Data about vessel type, location and time of wrecks and damages, weather and ice conditions, description of events has been organized into a data base. For many accidents information on distinguished features and the behaviour of humans in the Arctic waters (reactions in stressful situations and reasons for deaths) has been collected. -

Arctic Climate Variability and Ice Regime of the Lena River Delta Lakes

E3S Web of Conferences 163, 04008 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202016304008 IV Vinogradov Conference Arctic climate variability and ice regime of the Lena River delta lakes Roman Zdorovennov1,*, Sergey Golosov2, Ilya Zverev2, Galina Zdorovennova1 , and Irina Fedorova3 1Northern Water Problems Institute, KarRC RAS, 185030 A. Nevsky aven., 50, Petrozavodsk, Russia 2Institute of Limnology RAS, 196105, Sevastianov str., 9, St. Petersburg, Russia 3St.-Petersburg State University, 199034, Universitetskaya nab., 7-9, St. Petersburg, Russia Abstract. Climate variability in the Russian Arctic in 1991-2017 is examined based on the mesurements of the air temperature at 19 meteorological stations. The average annual air temperature at the stations fluctuated relative to the climatic baseline of 1961-1990 by 0.5-4°C in 1991-2004. Since 2005, it was higher than the climatic baseline at all stations annually. The increase in the air temperature was most pronounced in the winter months from November to February at all stations (more than 15ºɋ at some stations in some years). The increase in the air temperature in the summer months was noticeably smaller. The baseline level of the average monthly air temperature from November to February was exceeded most prominently at high latitude meteorological stations located at Wiese Island, Severnaya Zemlya, and Franz Josef Land (16-17ºɋ in some years, starting with 2005). Stations located at a distance from the ocean, such as Khatanga and Tiksi, are characterized by a smaller temperature increase compared to coastal and island stations, such as Barenzburg, Wrangel Island and others. Smaller deviations of the air temperature from the baseline level are typical in the western sector of the Russian Arctic (Murmansk, Svyatoy Nose). -

Inventory of Arctic Observing Networks Russia

Inventory of Arctic Observing Networks Russia Version March 2010 Arctic Observing Networks - Russia Table of Contents 1. Overview of Approach (I.M. Ashik, AARI) 2. Review of State of Arctic Network of Hydrometeorological Observations (V.A. Romantsov, AARI) 3. Aerological Observation Network (A.P. Makshtas, AARI) 4. Observation of Solar Radiation in the Arctic (A.V Tsvetkov) 5. Oceanological Observations (I.M. Ashik, AARI) 6. Sea Level Observations (I.M. Ashik, AARI) 7. Sea Ice (A.V. Yulin, V.M. Smolyanitsky, AARI) 8. Hydrological Network of Observations of Water Bodies and Estuaries in the Russian Arctic (V.V. Ivanov, AARI) 9. Databases on Russian hydrometeorological observation and information Networks in the Arctic (A.A. Kuznetsov, RIHMI-WDC) 9.1.1 Terrestrial Meteorological Observations 9.1.2 Aerological Observations 9.1.3 Marine Meteorological Observations 9.2. Data on Regime and Resources of Surface Land Waters (Rivers and Channels) 9.3.1 Coastal Observations 9.3.2 Oceanographic Observations 10. Permafrost Observations Network (O.A. Anisimov, SHI) 11. Glacier Observation Network (Ananicheva, RAS IO) 12. Arctic Environmental Pollution Observation Network (S.S. Krylov, North-West Branch, SPA Typhoon) 13. Biodiversity Monitoring in the Arctic (M.V. Gavrilo, AARI) 14. Integrated Arctic Socially-oriented Observation System (IASOS) Network (T.K. Vlasova, RAS IO) 15. Human Health (V.P. Chaschin, North-West Scientific Center of Hygiene and Public Health) 1. Overview of Approach Networks, points and programs of observation in the Russian Arctic can be classified by their thematic, territorial or departmental belongings. Thematically observation networks can be divided into: 1. Hydrometeorological – observing the Arctic atmosphere and hydrosphere 2. -

Coastal Marine Institute

University of Alaska Coastal Marine Institute . Proceedings of a Workshop on Small-Scale Sea-Ice and Ocean Modeling (SIOM) in the Nearshore Beaufort and Chukchi Seas Jia Wang, Principal Investigator University of Alaska Fairbanks Final Report July 2003 OCS Study MMS 2003-043 This study was funded in part by the U.S. Department of the Interior, Minerals Management Service (MMS), through Cooperative Agreement No. 1435-01-98-CA-30909, Task Order No. 85238, between the MMS, Alaska Outer Continental Shelf Region, and the University of Alaska Fairbanks. The opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this report or product are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Minerals Management Service, nor does mention of trade names of commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the Federal Government. OCS Study MMS 2003-043 Final Report Proceedings of a Workshop on Small-Scale Sea-Ice and Ocean Modeling (SIOM) in the Nearshore Beaufort and Chukchi Seas by Jia Wang Principal Investigator Frontier Research System for Global Change International Arctic Research Center University of Alaska Fairbanks Fairbanks, AK 99775-7335 E-mail: jwangiarc.uaf.edu July 2003 Contact information e-mail: [email protected] phone: 907.474.7707 fax: 907.474.7204 postal: Coastal Marine Institute School of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences University of Alaska Fairbanks Fairbanks, AK 99775-7220 Table of Contents List of Figures iv Abstract 1 Introduction 1 Present Progress 2 Sea-ice modeling 2 Coupled -

Progress in Oceanography Progress in Oceanography 71 (2006) 288–313

Progress in Oceanography Progress in Oceanography 71 (2006) 288–313 www.elsevier.com/locate/pocean Structure and function of contemporary food webs on Arctic shelves: A panarctic comparison The pelagic system of the Kara Sea – Communities and components of carbon flow H.J. Hirche a,*, K.N. Kosobokova b, B. Gaye-Haake c, I. Harms d, B. Meon a, E.-M. No¨thig a a Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, Columbusstrasse 1, D-27568 Bremerhaven, Germany b Shirshov Institute of Oceanology, RAS, Moscow, Russia c Centre for Marine and Climate Research, Institute for Biogeochemistry and Marine Chemistry, Hamburg, Germany d Centre for Marine and Climate Research, Institute for Oceanography, Hamburg, Germany Abstract After a short introduction to the physical setting and the history of biological research the pelagic ecosystem of the Kara Sea is described. Main emphasis is on regional aspects of the plankton communities and their seasonal dynamics using mostly data collected between 1996 and 2001. In the zooplankton, for which most data were available, four regional aggregations were separated: (1) the rivers and estuaries of the Southern Kara Sea, (2) the south-western and (3) the central Kara Sea, and (4) the northern troughs and slope. The phytoplankton communities had a similar distribution. To provide components for detailed carbon budgets the regional dynamics of bacterial, phytoplankton and zooplankton biomass and production are described and carbon requirements of bacteria and zooplankton are estimated. For completeness a short literature review on higher trophic levels is included. Finally, recent observations of the pelago-benthic coupling are con- sidered. -

History of the Northern Sea Route

1 History of the Northern Sea Route ``History is a lantern to the future, which shines to us from the past'' V.O. Klyuchevskiy 1.1 FIRST VOYAGES (V.Ye. Borodachev, V.Yu. Alexandrov) The history of the exploration of the North is full of heroic spirit andtragedyÐthe voyages andexpeditionsthat accompaniedgeographical discoveriesÐthe history of scienti®c studiesÐorganization of a system of stationary and non-stationary observa- tionsÐcreation of the scienti®c±technical support service for the Northern Sea Route (NSR)Ðall in all, the history of a ®erce battle against the incredibly severe conditions of the Arctic. It is challenging to comprehensively reconstruct the backgroundto this history. The famous Norwegian polar explorer andscientist Fridtjof Nansen wrote: ``We speak about the ®rst discovery of the NorthÐbut how can we know when the ®rst man appearedin the Earth's northern regions? We know nothing except for the very last migration stages of humanity. What occurredduring these long centuries is still hidden from us'' (Nansen, 1911). Indeed, we have some evidence on Pytheas, a Greek from Massalia, who between 350 and310 bc reachedEnglandandthen a ``gloomy land''he calledThule, beyond which ``there is no sea or landor air with some mixture of all these elements hanging in space'' (Belkin, 1983). Such a perception of the earth's northern regions was preserved for many centuries andonly began to change in the 9th to 11th centuries with the appearance of ®rst the Norsemen in the Barents andWhite Seas. Between 870 and 890 ad, more than a thousandyears after the voyage of Pytheas, the Norwegian seafarer Ottar rounded the northern tip of Europe and explored the Barents and White Seas. -

Nuclear Explosions in the USSR: the North Test Site Reference Material

NUCLEAR EXPLOSIONS IN THE USSR: THE NORTH TEST SITE REFERENCE MATERIAL VERSION 4 DECEMBER 2004 The originating Division of this publication in the IAEA was: The Division of Nuclear Safety and Security International Atomic Energy Agency Wagramer Strasse 5 P.O. Box 100 A-1400 Vienna, Austria FOREWORD During the last decade a number of publications have been issued containing information about the past nuclear weapons tests and their radiological consequences for the environment and the public. In Russia, monographs devoted to operation of the Semipalatinsk Test Site, Kazakhstan, and the North Test Site, located on the Novaya Zemlya archipelago in the Arctic Ocean, were recently published as well as a monograph devoted to the peaceful underground nuclear explosions. This document contains reference materials and papers of Russian experts presented at international and national scientific meetings and public hearings devoted to operation of the North Test Site and the radiological impact of nuclear weapons testing. These materials were originally published in Russia in 1993 and the second edition in 1999 as “Nuclear Explosions in the USSR: The North Test Site, Reference material on nuclear explosions, radiology, radiation safety”. The monograph was published by the Interagency Expert Commission on assessment of radiation and seismic safety of underground nuclear tests, Scientific-Industrial Association“V.G. Khlopin Radium Institute”, Russian Nuclear Society (Section: Environmental aspects of nuclear power), and the Centre for Public Information on Nuclear Power. The second, corrected and extended edition, edited by Academician V. N. Mikhailov, Dr. Yu. V. Dubasov and Prof. A. M. Matushchenko is the first issue containing detailed reference materials on nuclear explosions for the period 1955–1990 at the North Test Site, and on the radiation situation on its territory and in adjacent regions.