Indo 17 0 1107130745 161

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Report Phase I 1997-2001 Technical Report Phase I 1997-2001

cvr_itto 4/10/02 10:06 AM Page 1 Technical Report Phase I 1997-2001 Technical Technical Report Phase I 1997-2001 ITTO PROJECT PD 12/97 REV.1 (F) Forest, Science and Sustainability: The Bulungan Model Forest ITTO project PD 12/97 Rev. 1 (F) project PD 12/97 Rev. ITTO ITTO Copyright © 2002 International Tropical Timber Organization International Organization Center, 5th Floor Pacifico - Yokohama 1-1-1 Minato - Mirai, Nishi - ku Yokohama - City, Japan 220-0012 Tel. : +81 (45) 2231110; Fax: +81 (45) 2231110 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.itto.or.jp Center for International Forestry Research Mailing address: P.O. Box 6596 JKPWB, Jakarta 10065, Indonesia Office address: Jl. CIFOR, Situ Gede, Sindang Barang, Bogor Barat 16680, Indonesia Tel.: +62 (251) 622622; Fax: +62 (251) 622100 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.cifor.cgiar.org Financial support from the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO) through the Project PD 12/97 Rev.1 (F), Forest, Science and Sustainability: The Bulungan Model Forest is gratefully acknowledged ii chapter00 2 4/8/02, 2:50 PM Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations iv Foreword vi Acknowledgements viii Executive summary ix 1. Introduction 1 2. Overview of Approaches and Methods 4 3. General Description of the Bulungan Research Forest 8 4. Research on Logging 23 4.a. Comparison of Reduced-Impact Logging and Conventional Logging Techniques 23 4.b. Reduced-Impact Logging in Indonesian Borneo: Some Results Confirming the Need for New Silvicultural Prescriptions 26 4.c. Cost-benefit Analysis of Reduced-Impact Logging in a Lowland Dipterocarp Forest of Malinau, East Kalimantan 39 5. -

Release from Batara Kala's Grip: a Biblical Approach to Ruwatan From

ERT (2019) 43:2, 126-137 Release from Batara Kala’s Grip: A Biblical Approach to Ruwatan from the Perspective of Paul’s Letter to the Ephesians Pancha W. Yahya Ruwatan is a ritual that has been Ruwatan is derived from a Hindu practiced by the Javanese people (the - largest ethnic group in Indonesia) for cation or liberation of gods who had centuries.1 The word ruwatan comes traditionbeen cursed and for is makingrelated mistakesto the purifi and from ruwat, which means ‘to free’ or changed into other beings (either hu- ‘to liberate’. Ruwatan is ‘a ritual to lib- mans or animals). erate certain people because it is be- Because of the widespread practice lieved that they will experience bad of ruwatan, a biblical perspective on luck.’2 These people are considered - donesian Christians, especially those Batara Kala, an evil god of gigantic thisfrom ritual a Javanese would cultural be beneficial background. to In uncleanproportions and firmlyin Javanese under mythology.the grip of Paul’s epistle to the Ephesians pro- The ritual is practised by every stra- vides such a perspective, as it directly tum of the Javanese society—wealthy addresses the evil powers and their and poor, educated and illiterate.3 ability to bind people.4 Ephesus was known as the centre of magic in the Graeco-Roman world.5 1 - I will begin by describing the prac- tral Java and East Java and also the Yogyakar- tice and implicit worldview of ruwa- ta special The Javanese region, live all onin thethe provincesisland of Java, of Cen In- tan. -

THE PERCEPTION of COASTAL COMMUNITY of MANGROVES in SULI SUBDISTRICT, LUWU by Bustam Sulaiman

THE PERCEPTION OF COASTAL COMMUNITY OF MANGROVES IN SULI SUBDISTRICT, LUWU by Bustam Sulaiman Submission date: 18-Nov-2019 07:47PM (UTC-0800) Submission ID: 1216836611 File name: LUTFI_2.docx (103.65K) Word count: 4691 Character count: 26032 THE PERCEPTION OF COASTAL COMMUNITY OF MANGROVES IN SULI SUBDISTRICT, LUWU ORIGINALITY REPORT 7% 5% 5% 4% SIMILARITY INDEX INTERNET SOURCES PUBLICATIONS STUDENT PAPERS PRIMARY SOURCES gre.magoosh.com 1 Internet Source 1% report.ipcc.ch 2 Internet Source 1% Tri Joko, Sutrisno Anggoro, Henna Rya Sunoko, 3 % Savitri Rachmawati. "Pesticides Usage in the 1 Soil Quality Degradation Potential in Wanasari Subdistrict, Brebes, Indonesia", Applied and Environmental Soil Science, 2017 Publication Submitted to Southern Illinois University 4 Student Paper <1% Yangfan Li, Xiaoxiang Zhang, Xingxing Zhao, 5 % Shengquan Ma, Huhua Cao, Junkuo Cao. <1 "Assessing spatial vulnerability from rapid urbanization to inform coastal urban regional planning", Ocean & Coastal Management, 2016 Publication "Microorganisms in Saline Environments: 6 Strategies and Functions", Springer Science and Business Media LLC, 2019 <1% Publication Bustam Sulaiman, Azis Nur Bambang, 7 % Mohammad Lutfi. " Mangrove Cultivation ( ) as <1 an Effort for Mangrove Rehabilitation in the Ponds Bare in Belopa, Luwu Regency ", E3S Web of Conferences, 2018 Publication abyiogren.meb.gov.tr 8 Internet Source <1% ufdc.ufl.edu 9 Internet Source <1% ejournal2.undip.ac.id 10 Internet Source <1% Shin Hye Kim, Min Kyung Oh, Ran Namgung, 11 % Mi Jung Park. "Prevalence of 25-hydroxyvitamin <1 D deficiency in Korean adolescents: association with age, season and parental vitamin D status", Public Health Nutrition, 2012 Publication link.springer.com 12 Internet Source <1% worldwidescience.org 13 Internet Source <1% Mohammad Lutfi, Muh Yamin, Mujibu Rahman, 14 % Elisa Ginsel Popang. -

I La Galigo a Visionary Work for the Theatre Inspired by Sureq Galigo, an Epic Poem from South Sulawesi, Indonesia

I La Galigo A visionary work for the theatre inspired by Sureq Galigo, An epic poem from South Sulawesi, Indonesia August 7‐10, 2008 Taipei Metropolitan Hall Credits Direction, set design, lighting concept Robert Wilson Text adaptation and dramaturgy Rhoda Grauer Music Rahayu Supanggah Artistic coordination Restu I Kusumaningrum Costume designer Joachim Herzog Co‐director Ann Christin Rommen Lighting designer AJ Weissbard Collaborator to set design Christophe Martin Textile design and costume coordination Yusman Siswandi and Airlangga Komara Dance master Andi Ummu Tunru Assistant director Rama Soeprato Cast Abdul Murad, Amri Asrun, Ascafeony Daengtanang, B. Kristiono Soewardjo, Coppong Binti Baco, Didi Annuriansyah, Erythrina Baskorowati, Faizal Yunus, Herry Yotam, I Gede Sudiarcana, I Ketut Rina, Indrayani Djamaluddin, Indra Widaryatno, Iwan Wiyanto, Jusneni Fachruddin, Kadek Tegeh Okta WM, Kinanti Reski, Muhammad Agung, M. Gentille , Murniati, Ni Made Sumartini, Ridwan Anwar, Samsari Hatipe, Satriani Kamaluddin, Sefi Indah Prawarsari, Simson Lawari, Harlina Darni, Sri Qadariatin, Taufiq Ismail, Tenri Lebbi, Wangi Indriya, Widyawati, Yusan Budiawan Nadjamuddin, Zulsafri Nurdin Musicians Rahayu Supanggah (music director), Abdul Bashit, Anusirwan, Arifin Manggau, Basri Baharuddin Sila, Hamrin Samad, I Wayan Sadera, Imran Rauf, Danis Sugiyanto, Peni Candra Rini, Solihing Bin Dorahing, Sri Joko Raharjo, Zamratul Fitria and Puang Matoa Saidi 1 1 Technical Director Amerigo Varesi; Stage manager Evelyn Chia; Assistant stage manager Tinton Prianggoro; -

Provisional Reel List

Manuscripts of the National Library of Indonesia Reel no. Title MS call no. 1.01 Lokapala CS 1 1.02 Sajarah Pari Sawuli CS 2 1.03 Babad Tanah Jawi CS 3 2.01 Pratelan Warni-warni Bab Sajarah Tanah Jawa CS 4 2.02 Damarwulan CS 5 2.03 Menak Cina CS 6 3.01 Kakawin Bharatayuddha (Bratayuda Kawi) CS 7 3.02 Kakawin Bharatayuddha (Bratayuda Kawi) CS 9 3.03 Ambiya CS 10 4.01 Kakawin Bharatayuddha CS 11a 4.02 Menak Lare CS 13 4.03 Babad Tanah Jawi CS 14a 5.01 Babad Tanah Jawi CS 14b 5.02 Babad Tanah Jawi CS 14c 6.01 Babad Tanah Jawi CS 14d 6.02 Babad Tanah Jawi CS 14e 7.01 Kraton Surakarta, Deskripsi CS 17 7.02 Tedhak Dalem PB IX Dhateng Tegalganda CS 18 7.03 Serat Warni-warni CS 19 7.04 Babad Dipanagara lan Babad Nagari Purwareja KBG 5 8.01 Platuk Bawang, Serat CS 20 8.02 Wulang Reh CS 21 8.03 Cabolek, Serat CS 22 8.04 Kancil CS25 8.05 Carakabasa CS 27 8.06 Manuhara, Serat CS 29 8.07 Pawulang Ing Budi, Serat CS 30 8.08 Babad Dipanegara CS 31a 8.09 Dalil, Serat CS 28 9.01 Kraton Surakarta, Deskripsi CS 32 9.02 Primbon Matan Sitin CS 33 9.03 Harun ar-Rasyid, Cerita CS 34 9.04 Suluk Sukarsa CS 35 9.05 Murtasiyah CS 36 9.06 Salokantara CS 37 9.07 Panitipraja lsp CS 38 9.08 Babasan Saloka Paribasan CS 39 9.09 Babad Siliwangi CS 40 9.10 Dasanama Kawi Jarwa (Cirebonan) CS 42 9.11 Primbon Br 139 9.12 Pantitipraja lap KBG 343 10.01 Babad Dipanegara CS 31b 10.02 Babad Tanah Jawi (Adam - Jaka Tingkir) KBG 7a 11.01 Babad Tanah Jawi KBG 7c 11.02 Babad Tanah Jawi KBG 7d 11.03 Babad Tanah Jawi KBG 7e 11.04 Purwakanda Br 103a 12.01 Purwakanda Br 103b 12.02 Purwakandha Br 103c 12.03 Purwakandha Br 103d Reel no. -

05-06 2013 GPD Insides.Indd

Front Cover [Do not print] Replace with page 1 of cover PDF WILLIAM CAREY LIBRARY NEW RELEASE Developing Indigenous Leaders Lessons in Mission from Buddhist Asia (SEANET 10) Every movement is only one generation from dying out. Leadership development remains the critical issue for mission endeavors around the world. How are leaders developed from the local context for the local context? What is the role of the expatriate in this process? What models of hope are available for those seeking further direction in this area, particularly in mission to the Buddhist world of Asia? To answer these and several other questions, SEANET proudly presents the tenth volume in its series on practical missiology, Developing Indigenous Leaders: Lessons in Mission from Buddhist Asia. Each chapter in this volume is written by a practitioner and a mission scholar. Th e ten authors come from a wide range of ecclesial and national backgrounds and represent service in ten diff erent Buddhist contexts of Asia. With biblical integrity and cultural sensitivity, these chapters provide honest refl ection, insight, and guidance. Th ere is perhaps no more crucial issue than the development of dedicated indigenous leaders who will remain long after missionaries have returned home. If you are concerned about raising up leaders in your ministry in whatever cultural context it may be, this volume will be an important addition to your library. ISBN: 978-0-87808-040-3 List Price: $17.99 Paul H. De Neui Our Price: $14.39 WCL | Pages 243 | Paperback 2013 3 or more: $9.89 www.missionbooks.org 1-800-MISSION Become a Daily World Christian What is the Global Prayer Digest? Loose Change Adds Up! Th e Global Prayer Digest is a unique devotion- In adapting the Burma Plan to our culture, al booklet. -

Local Trade Networks in Maluku in the 16Th, 17Th and 18Th Centuries

CAKALELEVOL. 2, :-f0. 2 (1991), PP. LOCAL TRADE NETWORKS IN MALUKU IN THE 16TH, 17TH, AND 18TH CENTURIES LEONARD Y. ANDAYA U:-fIVERSITY OF From an outsider's viewpoint, the diversity of language and ethnic groups scattered through numerous small and often inaccessible islands in Maluku might appear to be a major deterrent to economic contact between communities. But it was because these groups lived on small islands or in forested larger islands with limited arable land that trade with their neighbors was an economic necessity Distrust of strangers was often overcome through marriage or trade partnerships. However, the most . effective justification for cooperation among groups in Maluku was adherence to common origin myths which established familial links with societies as far west as Butung and as far east as the Papuan islands. I The records of the Dutch East India Company housed in the State Archives in The Hague offer a useful glimpse of the operation of local trading networks in Maluku. Although concerned principally with their own economic activities in the area, the Dutch found it necessary to understand something of the nature of Indigenous exchange relationships. The information, however, never formed the basis for a report, but is scattered in various documents in the form of observations or personal experiences of Dutch officials. From these pieces of information it is possible to reconstruct some of the complexity of the exchange in MaJuku in these centuries and to observe the dynamism of local groups in adapting to new economic developments in the area. In addition to the Malukans, there were two foreign groups who were essential to the successful integration of the local trade networks: the and the Chinese. -

The Journal of Social Sciences Research ISSN(E): 2411-9458, ISSN(P): 2413-6670 Vol

The Journal of Social Sciences Research ISSN(e): 2411-9458, ISSN(p): 2413-6670 Vol. 6, Issue. 4, pp: 399-405, 2020 Academic Research Publishing URL: https://arpgweb.com/journal/journal/7 Group DOI: https://doi.org/10.32861/jssr.64.399.405 Original Research Open Access The Role of Minangkabau Ulamas in the Islamization of the Kingdoms of Gowa and Tallo Nelmawarni Nelmawarni* Department of Islamic History, Center for Graduate Management UIN Imam Bonjol Padang, 25153 Padang, West Sumatra, Indonesia Martin Kustati Department of English, Faculty of Islamic Education and Teacher Training UIN Imam Bonjol Padang, 25153 Padang, West Sumatra, Indonesia Hetti Waluati Triana Deparment of Language and Literature, Faculty of Adab and Humanities UIN Imam Bonjol Padang, 25153 Padang, West Sumatra, Indonesia Firdaus Firdaus Department of Islamic Law, Center for Graduate Management UIN Imam Bonjol Padang, 25153 Padang, West Sumatra, Indonesia Warnis Warnis Community Service and Research Center UIN Imam Bonjol Padang, 25153 Padang, West Sumatra, Indonesia Abstract The study aims to explain the important role of Minangkabau ulamas in the Islamization of the Bugis kingdoms in South Sulawesi. The historical approach was used in this study where the Heuristic activities were carried out to collect the main data. Document analysis of books, papers, journals and other relevant writings and interviews with customary figures were done. The results of the study found that the three ulamas came from Minangkabau and expertise in their respective fields and spread Islam. Datuk ri Bandang, who lived in Gowa had expertised in the field of jurisprudence, taught and propagated Islam by using Islamic sharia as its core teaching. -

J. Hooykaas the Rainbow in Ancient Indonesian Religion In

J. Hooykaas The rainbow in ancient Indonesian religion In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 112 (1956), no: 3, Leiden, 291-322 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/28/2021 02:58:39PM via free access THE RAINBOW IN ANCIENT INDONESIAN RELIGION Still seems, as to my childhood's sight A midway station given For happy spirits to alight Betwixt the earth and heaven. THOMASCAMPBELL, TO the Rainbow st. 2 Introductwn. earth is not without a bond with heaven. The Bible tells US that in a fine passage, where the rainbow appeared as a token of Ethis bond, Gen. IX.13: I do set My bow in the cloud and it shall be for a token of a covenant between Me and the earth. The Greeks also knew, that, however easy-going their gods might be, there was a link between them and mortal men. That link was represented by Homer as the fleet-footed Iris, who with later poets became the personification of the rainbow. A beautiful picture of the Lord in a 12th century English psalter 1 shows that the rainbow also in Christian conception keeps its place as 'a token of a covenant', for Christ, in that picture, is seated on a rain- bow, with His feet nesting on a smaller bow. Thus we Europeans are acquainted with the rainbow as the bond between heaven and earth through both sources of culture which still nourish our civilisation. It hardly needs emphasizing, that each religion has its own view ofthe rainbow. -

The Edlergence of Early Kingdodls in South Sulawesi

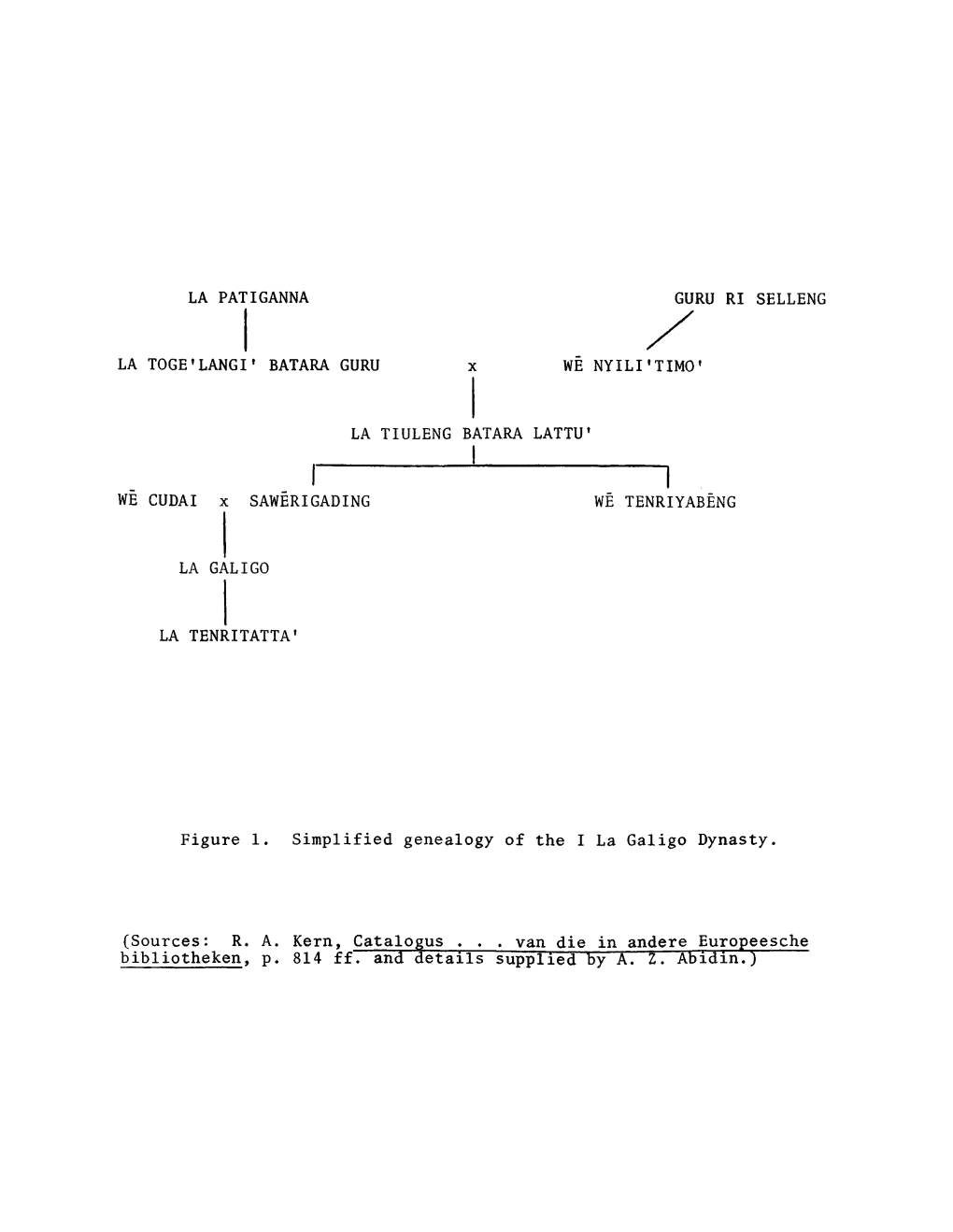

Southeast Asian Studies, Vo!. 20, No.4, March 1983 The EDlergence of Early KingdoDls in South Sulawesi --A Preliminary Remark on Governmental Contracts from the Thirteenth to the Fifteenth Century-- Andi' ZAINAL Abidin* III the I La Galigo Epic Cycle, Cina, later I Introduction called Pammana. Examples of such governmental contracts are found at the Pactum subjectionis or governmental beginning sections of historical chronicles contract is a covenant or compact between (Lontara' attoriolong),1> Usually the very the ruler and the ruled envisaging their first parts of the chronicles contain a mutual rights and responsibilities [Abidin political myth which explains the origin 1971: 159; Harvey 1974: 18; Riekerk of a dynasty as founded by a king or quoting Catlin 1969: 12]. Among the early queen descending from heaven. Thus prior states discussed by various scholars, e.g., to the emergence of kingdoms in South Claesen and Skalnik [1978], Geertz [1979], Sulawesi, the first king called To Manurung Selo Soemardjan [1978J, Coedes [1967J, 1) According to Andi' Makkaraka, the earliest Hall and Whitmore [Aeusrivongse 1979J, chronicles were composed in Luwu' before writ Reid and Castles [Macknight 1975J, none ings were known in other regions, and were subscribed to the practice of governmental called sure' attoriolong (document of ancient people) and the Sure' Galigo, I La Galigo Epic contracts, except Bone in South Sulawesi. Cycle. At first the Luwu' people used leaves of Despite its uniqueness, to my knowledge, the Aka' (Corypha Gebanga). Subsequently nothing has been written on the pactum writings appeared in other areas, notably Gowa and Tallo'. The Gowa people used leaves of subjectionis of early kingdoms in South the tala' tree (Borassus flabellzformis L.). -

The Indication of Sundanese Banten Dialect Shift in Tourism Area As Banten Society’S Identity Crisis (Sociolinguistics Study in Tanjung Lesung and Carita Beach)

International Seminar on Sociolinguistics and Dialectology: Identity, Attitude, and Language Variation “Changes and Development of Language in Social Life” 2017 THE INDICATION OF SUNDANESE BANTEN DIALECT SHIFT IN TOURISM AREA AS BANTEN SOCIETY’S IDENTITY CRISIS (SOCIOLINGUISTICS STUDY IN TANJUNG LESUNG AND CARITA BEACH) Alya Fauzia Khansa, Dilla Erlina Afriliani, Siti Rohmatiah Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT This research used theoretical sociolinguistics and descriptive qualitative approaches. The location of this study is Tanjung Lesung and Carita Beach tourism area, Pandeglang, Banten. The subject of this study is focused on Tanjung Lesung and Carita Beach people who understand and use Sundanese Banten dialect and Indonesian language in daily activity. The subject consists of 55 respondents based on education level, age, and gender categories. The data taken were Sundanese Banten dialect speech act by the respondents, both literal and non-literal speech, the information given is the indication of Sundanese Banten dialect shift factors. Data collection technique in this research is triangulation (combination) in the form of participative observation, documentation, and deep interview by using “Basa Urang Project” instrument. This research reveals that the problems related to the indication of Sundanese Banten dialect shift in Tanjung Lesung and Banten Carita Beach which causes identity crisis to Tanjung Lesung and Banten Carita Beach people. This study discovers (1) description of Bantenese people local identity, (2) perception of Tanjung Lesung and Carita Beach people on the use of Sundanese Banten dialect in Tanjung Lesung and Carita Beach tourism area and (3) the indications of Sundanese Banten dialect shift in Tanjung Lesung and Carita Beach tourism area. -

Oral and Written Traditions of Buginese: Interpretation Writing Using the Buginese Language in South Sulawesi

Volume-23 Issue-4 ORAL AND WRITTEN TRADITIONS OF BUGINESE: INTERPRETATION WRITING USING THE BUGINESE LANGUAGE IN SOUTH SULAWESI 1Muhammad Yusuf, 2Ismail Suardi Wekke Abstract---The uniqueness of the Buginese tribe is in the form of its oral and written traditions that go hand in hand. Oral tradition is supported by the Lontarak Manuscript which consists of Lontarak Pasang, Attoriolong, and Pau-pau ri Kadong. On the other hand, the Buginese society has the Lontarak script, which supports the written tradition. Both of them support the transmission of the knowledge of the Buginese scholars orally and in writing. This study would review the written tradition of Buginese scholars who produce works in the forms of interpretations using the Buginese language. They have many works in bequeathing their knowledge, which is loaded with local characters, including the substance and medium of the language. The embryonic interpretation began with the translation works and rubrics. Its development can be divided based on the characteristics and the period of its emergence. The First Period (1945 – 1960s) was marked by copying interpretations from the results of scholars’ reading. The Second Period (the mid-1960s – 1980s) was marked by the presence of footnotes as needed, translations per word, simple indexes, and complete interpretations with translations and comments. The Third Period (the 1980s – 2000s) started by the use of Indonesian and Arabic languages and the maintenance and development of local interpretations in Buginese, Makassarese, Tator, and Mandar. The scholar adapts this development while maintaining local treasures. Keywords---Tradition, Buginese, Scholar, Interpretation, Lontarak I. Introduction Each tribe has its characteristics and uniqueness as the destiny of life and ‘Divine design’ (sunnatullah) (Q.s.