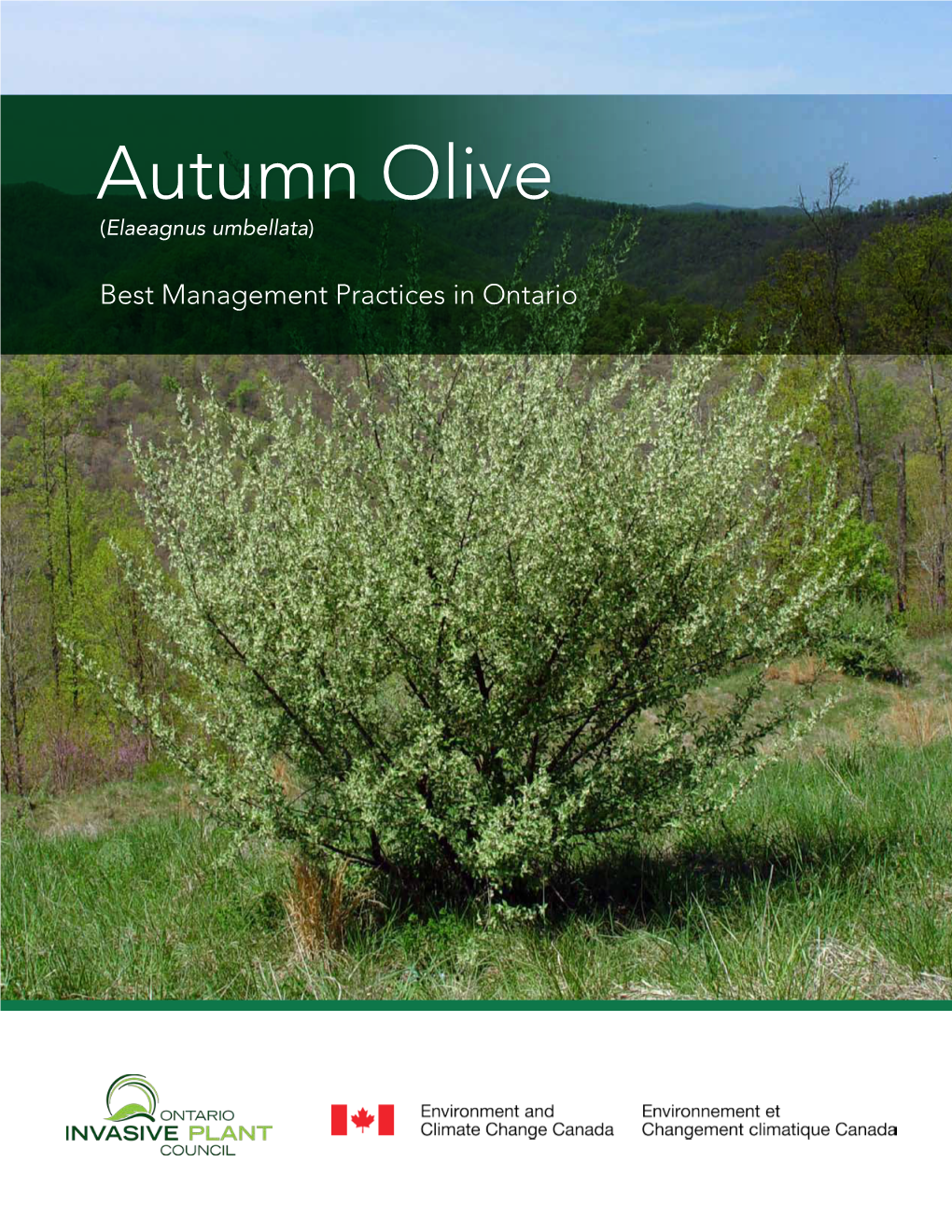

Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus Umbellata)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ON the WOODY PLANTS of Llasca PARK a MAJOR REPORT

.. \ PATTERNS AND INTEI~ SITY OF WHI'l'E•TAILED DEER BROWSING ON THE WOODY PLANTS OF llASCA PARK ~ -·• .-:~~ -"7,"l!'~C .-'";"'l.;'3. • ..., 1; ;-:_ . .. ..... .. ;_., ( •• ~ -· ., : A MAJOR REPORT ~ i ..,; ·:-.:.. _, j i... ...... .. .' J £70 q ... c a:s·:, >rse·- _....,. •e '~· SUBMITTED TO THE.. SCHOOL OF FORESTRY By DONALD N. ORKE •' IN: PARTIAL FULFILU1ENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS. FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE OCTOBER, 1966 - .. ,,..\ ., ..- ./ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to thank the School of Forestry . :-~~ ..·,. for providing the, financial assistance needed to conduct the study. Also, special thf.llks ·are due to Dr. Henry L. Hansen who provided help:f'ul advice in th• preparation of. this report • .. - ' TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 1 HISTORY OF THE ITASCA DEER HERD AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE VEGETATION ••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •••••••••• 2 LITERATURE REVIEW •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 5 STUDY AREA ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• • 11 METH<D.DS:i •••• . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .•• 13 RESULTS BROWSE PREFERENCES ••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 17 BROWSING ON KONIFER SEEDLINGS •••••••••••••••• 40 DISCUSSION BROWSE PREFERENCES ••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 51 BROWSING ON CONIFER SEEDLINGS •• • • • • • • • • • • • • • .54 SUGGESTIONS FOR FUTURE STUDIES ••••••••••••••• 56 SUMMA.RY • •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 5 7 LITERATURE CITED ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• a.• .. 59 APPENDIX •••••••••••••••••••••• e ••••••••••••••••••••• 61 ,-·. INTRODUCTION -

Plant Materials Tech Note

United States Department of Agriculture NATURAL RESOURCES CONSERVATION SERVICE Plant Materials Plant Materials Technical Note No. MT-33 September 1999 PLANT MATERIALS TECH NOTE DESCRIPTION, PROPAGATION, AND USE OF SILVERBERRY Elaeagnus commutata. Introduction: Silverberry Elaeagnus commutata Bernh. ex. Rydb is a native shrub with potential use in streambank stabilization, wildlife habitat, windbreaks, and naturalistic landscaping projects. The purpose of this bulletin is to transfer information on the identification, culture, and proper use of this species. FIGURE 1 FRUIT STEM FOLIAGE I. DESCRIPTION Silverberry is a multi-stemmed, deciduous shrub ranging from 1.5 to 3.6 m (5 to 12 ft.) tall. In Montana, heights of 1.5 to 2.4 m (5 to 8 ft.) are most common. It has an erect, upright habit with slender and sometimes twisted branches. The new stems are initially a light to medium brown color, the bark becoming dark gray, but remaining smooth, with age. The leaves are deciduous, alternate, 38 to 89 mm (1.5 to 3.5 in.) long and 19 to 38 mm (0.75 to 1.5 in.) wide (see Figure 1). The leaf shape is described as oval to narrowly ovate with an entire leaf margin. Both the upper and lower leaf surfaces are covered with silvery white scales, the bottom sometimes with brown spots. The highly fragrant, yellow flowers are trumpet-shaped (tubular), approximately 13 mm (0.5 in.) in length, and borne in the leaf axils in large numbers in May or June. The fruit is a silvery-colored, 7.6 mm (0.3 in.) long, egg-shaped drupe that ripens in September to October. -

Phylogeny and Phylogenetic Taxonomy of Dipsacales, with Special Reference to Sinadoxa and Tetradoxa (Adoxaceae)

PHYLOGENY AND PHYLOGENETIC TAXONOMY OF DIPSACALES, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO SINADOXA AND TETRADOXA (ADOXACEAE) MICHAEL J. DONOGHUE,1 TORSTEN ERIKSSON,2 PATRICK A. REEVES,3 AND RICHARD G. OLMSTEAD 3 Abstract. To further clarify phylogenetic relationships within Dipsacales,we analyzed new and previously pub- lished rbcL sequences, alone and in combination with morphological data. We also examined relationships within Adoxaceae using rbcL and nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences. We conclude from these analyses that Dipsacales comprise two major lineages:Adoxaceae and Caprifoliaceae (sensu Judd et al.,1994), which both contain elements of traditional Caprifoliaceae.Within Adoxaceae, the following relation- ships are strongly supported: (Viburnum (Sambucus (Sinadoxa (Tetradoxa, Adoxa)))). Combined analyses of C ap ri foliaceae yield the fo l l ow i n g : ( C ap ri folieae (Diervilleae (Linnaeeae (Morinaceae (Dipsacaceae (Triplostegia,Valerianaceae)))))). On the basis of these results we provide phylogenetic definitions for the names of several major clades. Within Adoxaceae, Adoxina refers to the clade including Sinadoxa, Tetradoxa, and Adoxa.This lineage is marked by herbaceous habit, reduction in the number of perianth parts,nectaries of mul- ticellular hairs on the perianth,and bifid stamens. The clade including Morinaceae,Valerianaceae, Triplostegia, and Dipsacaceae is here named Valerina. Probable synapomorphies include herbaceousness,presence of an epi- calyx (lost or modified in Valerianaceae), reduced endosperm,and distinctive chemistry, including production of monoterpenoids. The clade containing Valerina plus Linnaeeae we name Linnina. This lineage is distinguished by reduction to four (or fewer) stamens, by abortion of two of the three carpels,and possibly by supernumerary inflorescences bracts. Keywords: Adoxaceae, Caprifoliaceae, Dipsacales, ITS, morphological characters, phylogeny, phylogenetic taxonomy, phylogenetic nomenclature, rbcL, Sinadoxa, Tetradoxa. -

An Assessment of Autumn Olive in Northern U.S. Forests Research Note NRS-204

United States Department of Agriculture An Assessment of Autumn Olive in Northern U.S. Forests Research Note NRS-204 This publication is part of a series of research notes that provide an overview of the invasive plant species monitored on an extensive systematic network of plots measured by the Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) program of the U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station (NRS). Each research note features one of the invasive plants monitored on forested plots by NRS FIA in the 24 states of the midwestern and northeastern United States. Background and Characteristics Autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), a shrub of the Oleaster family (Elaeagnaceae), is native to eastern Asia and arrived in the United States in the 1830s. This vigorous invader was promoted for wildlife, landscaping, and erosion control. Tolerant of poor quality sites and full sun, it was often used for mine reclamation. Autumn olive disrupts native plant communities that require infertile soil by changing soil fertility through fixing nitrogen. Where it establishes, it can form dense thickets that shade out native plants (Czarapata 2005, Kaufman and Kaufman 2007, Kurtz 2013). Aside from the negative impact, autumn olive has important culinary and medicinal properties (Fordham et al. 2001, Guo et al. 2009). Figure 1.—Autumn olive flowers. Photo by Chris Evans, Description University of Illinois, from Bugwood.org, 1380001. Growth: woody, perennial shrub to 20 feet, often multi- stemmed; simple, alternate leaves with slightly wavy margins, green upper leaf surfaces, and silvery bottoms; shrubs leaf out early in the spring and retain leaves late in the fall. -

(Betula Papyrifera) / Diervilla Lonicera Trembling Aspen (Paper Birch) / Northern Bush-Honeysuckle Peuplier Faux-Tremble (Bouleau À Papier) / Dièreville Chèvrefeuille

Forest / Forêt Association CNVC 00238 Populus tremuloides (Betula papyrifera) / Diervilla lonicera Trembling Aspen (Paper Birch) / Northern Bush-honeysuckle Peuplier faux-tremble (Bouleau à papier) / Dièreville chèvrefeuille Subassociations: 238a typic, 238b Alnus viridis, 238c Kalmia angustifolia CNVC Alliance: CA00014 Betula papyrifera – Populus tremuloides – Abies balsamea / Clintonia borealis CNVC Group: CG0007 Ontario-Quebec Boreal Mesic Paper Birch – Balsam Fir – Trembling Aspen Forest Type Description Concept: CNVC00238 is a boreal hardwood forest Association that ranges from Manitoba to Quebec. It has a closed canopy dominated by trembling aspen ( Populus tremuloides ), usually with paper birch ( Betula papyrifera ), overtopping a well-developed to dense shrub layer. The shrub layer includes a mix of regenerating tree species, primarily trembling aspen, balsam fir ( Abies balsamea ), paper birch and black spruce ( Picea mariana ), as well as low shrub species, such as velvet-leaved blueberry ( Vaccinium myrtilloides ), northern bush-honeysuckle ( Diervilla lonicera ) and early lowbush blueberry ( V. angustifolium ). The herb layer is well developed and typically includes bunchberry (Cornus canadensis ), wild lily-of-the-valley ( Maianthemum canadense ), wild sarsaparilla ( Aralia nudicaulis ), yellow clintonia ( Clintonia borealis ), twinflower ( Linnaea borealis ) and northern starflower Source: Natural Resources Canada - (Lysimachia borealis ). The forest floor cover is mainly broad-leaf litter so the moss layer is Canadian Forest Service sparse, with only minor cover of red-stemmed feathermoss ( Pleurozium schreberi) . CNVC00238 is an early seral condition that typically establishes after fire or harvesting. It occurs in a region with a continental boreal climate that grades from subhumid in the west to humid in the east and is usually found on mesic, nutrient-medium sites. -

Plant List by Hardiness Zones

Plant List by Hardiness Zones Zone 1 Zone 6 Below -45.6 C -10 to 0 F Below -50 F -23.3 to -17.8 C Betula glandulosa (dwarf birch) Buxus sempervirens (common boxwood) Empetrum nigrum (black crowberry) Carya illinoinensis 'Major' (pecan cultivar - fruits in zone 6) Populus tremuloides (quaking aspen) Cedrus atlantica (Atlas cedar) Potentilla pensylvanica (Pennsylvania cinquefoil) Cercis chinensis (Chinese redbud) Rhododendron lapponicum (Lapland rhododendron) Chamaecyparis lawsoniana (Lawson cypress - zone 6b) Salix reticulata (netleaf willow) Cytisus ×praecox (Warminster broom) Hedera helix (English ivy) Zone 2 Ilex opaca (American holly) -50 to -40 F Ligustrum ovalifolium (California privet) -45.6 to -40 C Nandina domestica (heavenly bamboo) Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (bearberry - zone 2b) Prunus laurocerasus (cherry-laurel) Betula papyrifera (paper birch) Sequoiadendron giganteum (giant sequoia) Cornus canadensis (bunchberry) Taxus baccata (English yew) Dasiphora fruticosa (shrubby cinquefoil) Elaeagnus commutata (silverberry) Zone 7 Larix laricina (eastern larch) 0 to 10 F C Pinus mugo (mugo pine) -17.8 to -12.3 C Ulmus americana (American elm) Acer macrophyllum (bigleaf maple) Viburnum opulus var. americanum (American cranberry-bush) Araucaria araucana (monkey puzzle - zone 7b) Berberis darwinii (Darwin's barberry) Zone 3 Camellia sasanqua (sasanqua camellia) -40 to -30 F Cedrus deodara (deodar cedar) -40 to -34.5 C Cistus laurifolius (laurel rockrose) Acer saccharum (sugar maple) Cunninghamia lanceolata (cunninghamia) Betula pendula -

Elaeagnus Umbellata) on Reclaimed Surface Mineland at the Iw Lds Conservation Center in Southeastern Ohio Shana M

Western Washington University Masthead Logo Western CEDAR Huxley College on the Peninsulas Publications Huxley College on the Peninsulas 2012 Sustainable Landscapes: Evaluating Strategies for Controlling Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) on Reclaimed Surface Mineland at The iW lds Conservation Center in Southeastern Ohio Shana M. Byrd Conservation Science Training Center at the Wilds Nicole D. Cavender Morton Arboretum Corine M. Peugh Conservation Science Training Center at the Wilds Jenise Bauman Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/hcop_facpubs Part of the Botany Commons, and the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Byrd, Shana M.; Cavender, Nicole D.; Peugh, Corine M.; and Bauman, Jenise, "Sustainable Landscapes: Evaluating Strategies for Controlling Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) on Reclaimed Surface Mineland at The iW lds Conservation Center in Southeastern Ohio" (2012). Huxley College on the Peninsulas Publications. 12. https://cedar.wwu.edu/hcop_facpubs/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Huxley College on the Peninsulas at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Huxley College on the Peninsulas Publications by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal American Society of Mining and Reclamation, 2012 Volume 1, Issue 1 SUSTAINABLE LANDSCAPES: EVALUATING STRATEGIES FOR CONTROLLING AUTUMN OLIVE (ELAEAGNUS UMBELLATA) ON RECLAIMED SURFACE MINELAND AT THE WILDS CONSERVATION CENTER IN SOUTHEASTERN OHIO1 Shana M. Byrd2, Nicole D. Cavender, Corine M. Peugh and Jenise M. Bauman Abstract: Autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) was planted during the reclamation process to reduce erosion and improve nitrogen content of the soil. -

Distribution and Growth of Autumn Olive in a Managed Landscape

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2013 Distribution and growth of autumn olive in a managed landscape Matthew Ruddick Moore [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Forest Biology Commons, Other Forestry and Forest Sciences Commons, and the Plant Biology Commons Recommended Citation Moore, Matthew Ruddick, "Distribution and growth of autumn olive in a managed landscape. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2013. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1650 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Matthew Ruddick Moore entitled "Distribution and growth of autumn olive in a managed landscape." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Forestry. David S. Buckley, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Arnold M. Saxton, William E. Klingeman III Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Distribution and growth of autumn olive in a managed landscape A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Matthew Ruddick Moore May 2013 ii Copyright © Matthew R. -

Conservation Trees and Shrubs for Montana

Conservation Trees and Shrubs for Montana Montana mt.nrcs.usda.gov Introduction When you are contemplating which tree or shrub species to plant, your first thought might be, “Will this plant thrive here?” You will want to know if the plant will tolerate the temperatures, moisture, and soil conditions of the area. This publication focuses on identifying and describing trees and shrubs capable of tolerating Montana’s severe climatic and environmental conditions, the site conditions where they are best adapted to grow, and some of the benefits each tree and shrub provides. When looking at each of the provided attributes, consider these two points. First, these characteristics and traits are approximations, and variability within a species is quite common. Second, plant performance varies over time as a plant grows and matures. For example, even “drought tolerant” species require adequate moisture until their root systems become well established. Landowners and managers, homeowners, and others plant trees and shrubs for many reasons, including: windbreaks for livestock protection and crop production, shelterbelts for homes and farmsteads to reduce wind speed and conserve energy usage, living snow fences to trap and manage snow, hedgerows as visual and noise screens, landscaping for beautification around homes and parks, wildlife habitat and food, blossoms for pollinators such as bees, streamside and wetland restoration, reforestation following timber harvest or wildfire, and fruit and berries for human use to name just a few. Montana encompasses 93.3 million acres with temperature extremes ranging from -50 degrees F in northeast Montana, to 110 degrees F in summer in southcentral Montana. -

Autumn Olive Elaeagnus Umbellata Thunberg and Russian Olive Elaeagnus Angustifolia L

Autumn olive Elaeagnus umbellata Thunberg and Russian olive Elaeagnus angustifolia L. Oleaster Family (Elaeagnaceae) DESCRIPTION Autumn olive and Russian olive are deciduous, somewhat thorny shrubs or small trees, with smooth gray bark. Their most distinctive characteristic is the silvery scales that cover the young stems, leaves, flowers, and fruit. The two species are very similar in appearance; both are invasive, however autumn olive is more common in Pennsylvania. Height - These plants are large, twiggy, multi-stemmed shrubs that may grow to a height of 20 feet. They occasionally occur in a single-stemmed, more tree-like form. Russian olive in flower Leaves - Leaves are alternate, oval to lanceolate, with a smooth margin; they are 2–4 inches long and ¾–1½ inches wide. The leaves of autumn olive are dull green above and covered with silvery-white scales beneath. Russian olive leaves are grayish-green above and silvery-scaly beneath. Like many other non-native, invasive plants, these shrubs leaf out very early in the spring, before most native species. Flowers - The small, fragrant, light-yellow flowers are borne along the twigs after the leaves have appeared in May. autumn olive in fruit Fruit - The juicy, round, edible fruits are about ⅓–½ inch in diameter; those of Autumn olive are deep red to pink. Russian olive fruits are yellow or orange. Both are dotted with silvery scales and produced in great quantity August–October. The fruits are a rich source of lycopene. Birds and other wildlife eat them and distribute the seeds widely. autumn olive and Russian olive - page 1 of 3 Roots - The roots of Russian olive and autumn olive contain nitrogen-fixing symbionts, which enhance their ability to colonize dry, infertile soils. -

Introduction to Biogeography and Tropical Biology

Alexey Shipunov Introduction to Biogeography and Tropical Biology Draft, version April 10, 2019 Shipunov, Alexey. Introduction to Biogeography and Tropical Biology. This at the mo- ment serves as a reference to major plants and animals groups (taxonomy) and de- scriptive biogeography (“what is where”), emphasizing tropics. April 10, 2019 version (draft). 101 pp. Title page image: Northern Great Plains, North America. Elaeagnus commutata (sil- verberry, Elaeagnaceae, Rosales) is in front. This work is dedicated to public domain. Contents What 6 Chapter 1. Diversity maps ............................. 7 Diversity atlas .................................. 16 Chapter 2. Vegetabilia ............................... 46 Bryophyta ..................................... 46 Pteridophyta ................................... 46 Spermatophyta .................................. 46 Chapter 3. Animalia ................................ 47 Arthropoda .................................... 47 Mollusca ..................................... 47 Chordata ..................................... 47 When 48 Chapter 4. The Really Short History of Life . 49 Origin of Life ................................... 51 Prokaryotic World ................................ 52 The Rise of Nonskeletal Fauna ......................... 53 Filling Marine Ecosystems ............................ 54 First Life on Land ................................. 56 Coal and Mud Forests .............................. 58 Pangea and Great Extinction .......................... 60 Renovation of the Terrestrial -

Phylogenetics of the Caprifolieae and Lonicera (Dipsacales)

Systematic Botany (2008), 33(4): pp. 776–783 © Copyright 2008 by the American Society of Plant Taxonomists Phylogenetics of the Caprifolieae and Lonicera (Dipsacales) Based on Nuclear and Chloroplast DNA Sequences Nina Theis,1,3,4 Michael J. Donoghue,2 and Jianhua Li1,4 1Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University, 22 Divinity Ave, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 U.S.A. 2Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Yale University, P.O. Box 208106, New Haven, Conneticut 06520-8106 U.S.A. 3Current Address: Plant Soil, and Insect Sciences, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, Amherst, Massachusetts 01003 U.S.A. 4Authors for correspondence ([email protected]; [email protected]) Communicating Editor: Lena Struwe Abstract—Recent phylogenetic analyses of the Dipsacales strongly support a Caprifolieae clade within Caprifoliaceae including Leycesteria, Triosteum, Symphoricarpos, and Lonicera. Relationships within Caprifolieae, however, remain quite uncertain, and the monophyly of Lonicera, the most species-rich of the traditional genera, and its subdivisions, need to be evaluated. In this study we used sequences of the ITS region of nuclear ribosomal DNA and five chloroplast non-coding regions (rpoB–trnC spacer, atpB–rbcL spacer, trnS–trnG spacer, petN–psbM spacer, and psbM–trnD spacer) to address these problems. Our results indicate that Heptacodium is sister to Caprifolieae, Triosteum is sister to the remaining genera within the tribe, and Leycesteria and Symphoricarpos form a clade that is sister to a monophyletic Lonicera. Within Lonicera, the major split is between subgenus Caprifolium and subgenus Lonicera. Within subgenus Lonicera, sections Coeloxylosteum, Isoxylosteum, and Nintooa are nested within the paraphyletic section Isika. Section Nintooa may also be non-monophyletic.