An Assessment of Autumn Olive in Northern U.S. Forests Research Note NRS-204

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Systematikss11 8.Pdf

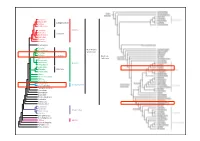

Asterales Dipsacales Campanulanae Apiales Aquifoliales Lamiales Asteridae Solanales Lamianae Gentianales Garryales Ericales Cornales Saxifragales Fagales Kern-Eudico- Cucurbitales tyledoneae Rosales Fabales Fabanae Eudicoty- Zygophyllales ledoneae Celastrales Oxalidales Rosidae Malpighiales Sapindales Malvales Malvanae Brassicales Vitales Crossosomatales Myrtales Geraniales Polygonales Caryophyllidae Caryophyllales Berberidopsidales Santalales Gunnerales Buxaceae Trochodendrales Proteales Sabiaceae Ranunculales Canellales Piperales Magnoliidae Magnoliales Laurales Chloanthaceae Ceratophyllaceae Liliidae Liliidae Austrobaileyales Nymphaeales Amborellales Klasse: Magnoliopsida (Angiospermae) Dicotyledoneae, Zweikeimblättrige Ordnung: Rosales Familie: Rhamnaceae (Kreuzdorngewächse) Merkmale: – Holzpflanzen mit wechselständigen oder gegenständigen, ungeteilten Blättern mit krautigen oder dornigen Nebenblättern – radiäre, kleine, gelblich-grüne, meist zwittrige Blüten – meist 5-zählige, selten 4-zählige Blüten – epipetal (= vor den Kronblättern stehende) Staubblätter – intrastaminaler Diskus – Perianth perigyn = mittelständiger Fruchtknoten, selten unterständig – Steinfrüchte, Nussfrüchte oder Spaltfrüchte Klasse: Magnoliopsida (Angiospermae) Dicotyledoneae, Zweikeimblättrige Ordnung: Rosales Familie: Rhamnaceae (Kreuzdorngewächse) Rhamnus frangula = Frangula alnus (Faulbaum) Kelchblatt Kronblatt Merkmale: – 5-zählige Blüte Staubblatt – Rinde mit grauweißen Korkwarzen (= Lentizellen) – Blätter elliptisch-eiförmig, ganzrandig – beerenähnliche -

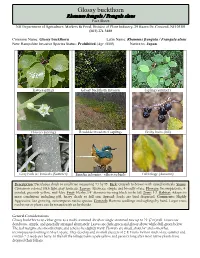

Glossy Buckthorn Rhamnusoriental Frangula Bittersweet / Frangula Alnus Control Guidelines Fact Sheet

Glossy buckthorn Oriental bittersweet Rhamnus frangula / Frangula alnus Control Guidelines Fact Sheet NH Department of Agriculture, Markets & Food, Division of Plant Industry, 29 Hazen Dr, Concord, NH 03301 (603) 271-3488 Common Name: Glossy buckthorn Latin Name: Rhamnus frangula / Frangula alnus New Hampshire Invasive Species Status: Prohibited (Agr 3800) Native to: Japan leaves (spring) Glossy buckthorn invasion Sapling (summer) Flowers (spring) Roadside invasion of saplings Fleshy fruits (fall) Gray bark w/ lenticels (Summer) Emodin in berries - effects to birds Fall foliage (Autumn) Description: Deciduous shrub or small tree measuring 20' by 15'. Bark: Grayish to brown with raised lenticels. Stems: Cinnamon colored with light gray lenticels. Leaves: Alternate, simple and broadly ovate. Flowers: Inconspicuous, 4- petaled, greenish-yellow, mid-May. Fruit: Fleshy, 1/4” diameter turning black in the fall. Zone: 3-7. Habitat: Adapts to most conditions including pH, heavy shade to full sun. Spread: Seeds are bird dispersed. Comments: Highly Aggressive, fast growing, outcompetes native species. Controls: Remove seedlings and saplings by hand. Larger trees can be cut or plants can be treated with an herbicide. General Considerations Glossy buckthorn can either grow as a multi-stemmed shrub or single-stemmed tree up to 23’ (7 m) tall. Leaves are deciduous, simple, and generally arranged alternately. Leaves are dark-green and glossy above while dull-green below. The leaf margins are smooth/entire and tend to be slightly wavy. Flowers are small, about ¼” and somewhat inconspicuous forming in May to June. They develop and in small clusters of 2-8. Fruits form in mid to late summer and contain 2-3 seeds per berry. -

FLORA from FĂRĂGĂU AREA (MUREŞ COUNTY) AS POTENTIAL SOURCE of MEDICINAL PLANTS Silvia OROIAN1*, Mihaela SĂMĂRGHIŢAN2

ISSN: 2601 – 6141, ISSN-L: 2601 – 6141 Acta Biologica Marisiensis 2018, 1(1): 60-70 ORIGINAL PAPER FLORA FROM FĂRĂGĂU AREA (MUREŞ COUNTY) AS POTENTIAL SOURCE OF MEDICINAL PLANTS Silvia OROIAN1*, Mihaela SĂMĂRGHIŢAN2 1Department of Pharmaceutical Botany, University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Tîrgu Mureş, Romania 2Mureş County Museum, Department of Natural Sciences, Tîrgu Mureş, Romania *Correspondence: Silvia OROIAN [email protected] Received: 2 July 2018; Accepted: 9 July 2018; Published: 15 July 2018 Abstract The aim of this study was to identify a potential source of medicinal plant from Transylvanian Plain. Also, the paper provides information about the hayfields floral richness, a great scientific value for Romania and Europe. The study of the flora was carried out in several stages: 2005-2008, 2013, 2017-2018. In the studied area, 397 taxa were identified, distributed in 82 families with therapeutic potential, represented by 164 medical taxa, 37 of them being in the European Pharmacopoeia 8.5. The study reveals that most plants contain: volatile oils (13.41%), tannins (12.19%), flavonoids (9.75%), mucilages (8.53%) etc. This plants can be used in the treatment of various human disorders: disorders of the digestive system, respiratory system, skin disorders, muscular and skeletal systems, genitourinary system, in gynaecological disorders, cardiovascular, and central nervous sistem disorders. In the study plants protected by law at European and national level were identified: Echium maculatum, Cephalaria radiata, Crambe tataria, Narcissus poeticus ssp. radiiflorus, Salvia nutans, Iris aphylla, Orchis morio, Orchis tridentata, Adonis vernalis, Dictamnus albus, Hammarbya paludosa etc. Keywords: Fărăgău, medicinal plants, human disease, Mureş County 1. -

Frangula Paruensis, a New Name for Rhamnus Longipes Steyermark (Rhamnaceae)

FRANGULA PARUENSIS, A NEW NAME FOR RHAMNUS LONGIPES STEYERMARK (RHAMNACEAE) GERARDO A. AYMARD C.1, 2 Abstract. The new name Frangula paruensis (Rhamnaceae) is proposed to replace the illegitimate homonym Rhamnus longipes Steyermark (1988). Chorological, taxonomic, biogeographical, and habitat notes about this taxon also are provided. Resumen. Se propone Frangula paruensis (Rhamnaceae) como un nuevo nombre para reemplazar el homónimo ilegítimo Rhamnus longipes Steyermark (1988). Se incluye información corológica, taxonómica, biogeográfica, y de hábitats acerca de la especie. Keywords: Frangula, Rhamnus, Rhamnaceae, Parú Massif, Tepuis flora, Venezuela Rhamnus L. and Frangula Miller (Rhamnaceae) have Frangula paruensis is a shrub, ca. 2 m tall, with leaves ca. 150 and ca. 50 species, respectively (Pool, 2013, 2015). ovate, or oblong-ovate, margin subrevolute, repand- These taxa are widely distributed around the world but are crenulate, a slightly elevated tertiary venation on the lower absent in Madagascar, Australia, and Polynesia (Medan and surface, and mature fruiting peduncle and pedicels 1–1.5 Schirarend, 2004). According to Grubov (1949), Kartesz cm long, and fruiting calyx lobes triangular-lanceolate and Gandhi (1994), Bolmgren and Oxelman (2004), and (two main features to separate Frangula from Rhamnus). Pool (2013) the recognition of Frangula is well supported. This species is endemic to the open, rocky savannas On the basis of historical and recent molecular work the on tepui slopes and summits at ca. 2000 m (Steyermark genus is characterized by several remarkable features. Pool and Berry, 2004). This Venezuelan taxon was described (2013: 448, table 1) summarized 11 features to separate the as Rhamnus longipes by Steyermark (1988), without two genera. -

Herb Other Names Re Co Rde D Me Dicinal Us E Re

RECORDED USE RECORDED USE MEDICINAL US AROMATHERA IN COSMETICS IN RECORDED RECORDED FOOD USE FOOD IN Y E P HERB OTHER NAMES COMMENTS Parts Used Medicinally Abelmoschus moschatus Hibiscus abelmoschus, Ambrette, Musk mallow, Muskseed No No Yes Yes Abies alba European silver fir, silver fir, Abies pectinata Yes No Yes Yes Leaves & resin Abies balsamea Balm of Gilead, balsam fir Yes No Yes Yes Leaves, bark resin & oil Abies canadensis Hemlock spruce, Tsuga, Pinus bark Yes No No No Bark Abies sibirica Fir needle, Siberian fir Yes No Yes Yes Young shoots This species not used in aromatherapy but Abies Sibirica, Abies alba Miller, Siberian Silver Fir Abies spectabilis Abies webbiana, Himalayan silver fir Yes No No No Essential Oil are. Leaves Aqueous bark extract which is often concentrated and dried to produce a flavouring. Distilled with Extract, bark, wood, Acacia catechu Black wattle, Black catechu Yes Yes No No vodka to make Blavod (black vodka). flowering tops and gum Acacia farnesiana Cassie, Prickly Moses Yes Yes Yes Yes Ripe seeds pressed for cooking oil Bark, flowers Source of Gum Arabic (E414) and Guar Gum (E412), controlled miscellaneous food additive. Used Acacia senegal Guar gum, Gum arabic No Yes No Yes in foods as suspending and emulsifying agent. Acanthopanax senticosus Kan jang Yes No No No Kan Jang is a combination of Andrographis Paniculata and Acanthopanax Senticosus. Flavouring source including essential oil. Contains natural toxin thujone/thuyone whose levels in flavourings are limited by EU (Council Directive 88/388/EEC) and GB (SI 1992 No.1971) legislation. There are several chemotypes of Yarrow Essential Oil, which is steam distilled from the dried herb. -

Section 317.1A (16, 2)

1 WEEDS, §317.1A 317.1A Noxious weeds. 1. The following weeds are hereby declared to be noxious and shall be divided into two classes, as follows: a. Primary noxious weeds, which shall include: (1) Quack grass (Elymus repens). (2) Perennial sow thistle (Sonchus arvensis). (3) Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense). (4) Bull thistle (Cirsium vulgare). (5) European morning glory or field bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis). (6) Horse nettle (Solanum carolinense). (7) Leafy spurge (Euphorbia esula). (8) Perennial pepper-grass (Cardaria draba). (9) Russian knapweed (Acroptilon repens). (10) Buckthorn (Rhamnus spp., not to include Frangula alnus, syn. Rhamnus frangula). (11) All other species of thistles belonging in the genera of Cirsium and Carduus. (12) Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri). b. Secondary noxious weeds, which shall include: (1) Butterprint (Abutilon theophrasti) annual. (2) Cocklebur (Xanthium strumarium) annual. (3) Wild mustard (Sinapis arvensis) annual. (4) Wild carrot (Daucus carota) biennial. (5) Buckhorn (Plantago lanceolata) perennial. (6) Sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella) perennial. (7) Sour dock (Rumex crispus) perennial. (8) Smooth dock (Rumex altissimus) perennial. (9) Poison hemlock (Conium maculatum). (10) Multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora). (11) Wild sunflower (wild strain of Helianthus annuus L.) annual. (12) Puncture vine (Tribulus terrestris) annual. (13) Teasel (Dipsacus spp.) biennial. (14) Shattercane (Sorghum bicolor) annual. 2. a. The multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora) shall not be considered a secondary noxious weed when cultivated for or used as understock for cultivated roses or as ornamental shrubs in gardens, or in any county whose board of supervisors has by resolution declared it not to be a noxious weed. b. Shattercane (Sorghum bicolor) shall not be considered a secondary noxious weed when cultivated or in any county whose board of supervisors has by resolution declared it not to be a noxious weed. -

Extended Leaf Phenology and the Autumn Niche in Deciduous Forest Invasions

LETTER doi:10.1038/nature11056 Extended leaf phenology and the autumn niche in deciduous forest invasions Jason D. Fridley1 The phenology of growth in temperate deciduous forests, including development, biweekly leaf production and chlorophyll (Chl) content, the timing of leaf emergence and senescence, has strong control over and monthly photosynthetic rate on select leaves at a range of light ecosystem properties such as productivity1,2 and nutrient cycling3,4, levels (50–800 mmol pm22 s21). Although not all species were mea- and has an important role in the carbon economy of understory sured each year, a similar number of native and non-native species plants5–7. Extended leaf phenology, whereby understory species were monitored annually and data sets for most species involved at assimilate carbon in early spring before canopy closure or in late least 2 years (Supplementary Table 1). autumn after canopy fall, has been identified as a key feature of The timing of leaf emergence across species was sensitive to inter- many forest species invasions5,8–10, but it remains unclear whether annual variation in spring temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 1), with there are systematic differences in the growth phenology of native all stages of bud development occurring several weeks earlier in the and invasive forest species11 or whether invaders are more responsive warmer spring of 2010 (P , 0.001, year contrasts in Mann–Whitney to warming trends that have lengthened the duration of spring or U-tests adjusted for multiple testing; Fig. 1). However, the timing of autumn growth12. Here, in a 3-year monitoring study of 43 native early stages of bud activity was not significantly different between and 30 non-native shrub and liana species common to deciduous native and non-native species for any year (Fig. -

Elaeagnus Umbellata) on Reclaimed Surface Mineland at the Iw Lds Conservation Center in Southeastern Ohio Shana M

Western Washington University Masthead Logo Western CEDAR Huxley College on the Peninsulas Publications Huxley College on the Peninsulas 2012 Sustainable Landscapes: Evaluating Strategies for Controlling Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) on Reclaimed Surface Mineland at The iW lds Conservation Center in Southeastern Ohio Shana M. Byrd Conservation Science Training Center at the Wilds Nicole D. Cavender Morton Arboretum Corine M. Peugh Conservation Science Training Center at the Wilds Jenise Bauman Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/hcop_facpubs Part of the Botany Commons, and the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Byrd, Shana M.; Cavender, Nicole D.; Peugh, Corine M.; and Bauman, Jenise, "Sustainable Landscapes: Evaluating Strategies for Controlling Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) on Reclaimed Surface Mineland at The iW lds Conservation Center in Southeastern Ohio" (2012). Huxley College on the Peninsulas Publications. 12. https://cedar.wwu.edu/hcop_facpubs/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Huxley College on the Peninsulas at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Huxley College on the Peninsulas Publications by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal American Society of Mining and Reclamation, 2012 Volume 1, Issue 1 SUSTAINABLE LANDSCAPES: EVALUATING STRATEGIES FOR CONTROLLING AUTUMN OLIVE (ELAEAGNUS UMBELLATA) ON RECLAIMED SURFACE MINELAND AT THE WILDS CONSERVATION CENTER IN SOUTHEASTERN OHIO1 Shana M. Byrd2, Nicole D. Cavender, Corine M. Peugh and Jenise M. Bauman Abstract: Autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) was planted during the reclamation process to reduce erosion and improve nitrogen content of the soil. -

A Phylogenetic Analysis of Rhamnaceae Using Rbcl and Trnl-F Plastid DNA Sequences James E. Richardson

A Phylogenetic Analysis of Rhamnaceae using rbcL and trnL-F Plastid DNA Sequences James E. Richardson; Michael F. Fay; Quentin C. B. Cronk; Diane Bowman; Mark W. Chase American Journal of Botany, Vol. 87, No. 9. (Sep., 2000), pp. 1309-1324. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0002-9122%28200009%2987%3A9%3C1309%3AAPAORU%3E2.0.CO%3B2-5 American Journal of Botany is currently published by Botanical Society of America. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/botsam.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. -

Distribution and Growth of Autumn Olive in a Managed Landscape

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2013 Distribution and growth of autumn olive in a managed landscape Matthew Ruddick Moore [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Forest Biology Commons, Other Forestry and Forest Sciences Commons, and the Plant Biology Commons Recommended Citation Moore, Matthew Ruddick, "Distribution and growth of autumn olive in a managed landscape. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2013. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1650 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Matthew Ruddick Moore entitled "Distribution and growth of autumn olive in a managed landscape." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Forestry. David S. Buckley, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Arnold M. Saxton, William E. Klingeman III Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Distribution and growth of autumn olive in a managed landscape A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Matthew Ruddick Moore May 2013 ii Copyright © Matthew R. -

Autumn Olive Elaeagnus Umbellata Thunberg and Russian Olive Elaeagnus Angustifolia L

Autumn olive Elaeagnus umbellata Thunberg and Russian olive Elaeagnus angustifolia L. Oleaster Family (Elaeagnaceae) DESCRIPTION Autumn olive and Russian olive are deciduous, somewhat thorny shrubs or small trees, with smooth gray bark. Their most distinctive characteristic is the silvery scales that cover the young stems, leaves, flowers, and fruit. The two species are very similar in appearance; both are invasive, however autumn olive is more common in Pennsylvania. Height - These plants are large, twiggy, multi-stemmed shrubs that may grow to a height of 20 feet. They occasionally occur in a single-stemmed, more tree-like form. Russian olive in flower Leaves - Leaves are alternate, oval to lanceolate, with a smooth margin; they are 2–4 inches long and ¾–1½ inches wide. The leaves of autumn olive are dull green above and covered with silvery-white scales beneath. Russian olive leaves are grayish-green above and silvery-scaly beneath. Like many other non-native, invasive plants, these shrubs leaf out very early in the spring, before most native species. Flowers - The small, fragrant, light-yellow flowers are borne along the twigs after the leaves have appeared in May. autumn olive in fruit Fruit - The juicy, round, edible fruits are about ⅓–½ inch in diameter; those of Autumn olive are deep red to pink. Russian olive fruits are yellow or orange. Both are dotted with silvery scales and produced in great quantity August–October. The fruits are a rich source of lycopene. Birds and other wildlife eat them and distribute the seeds widely. autumn olive and Russian olive - page 1 of 3 Roots - The roots of Russian olive and autumn olive contain nitrogen-fixing symbionts, which enhance their ability to colonize dry, infertile soils. -

Wide Spectrum of Active Compounds in Sea Buckthorn (Hippophae Rhamnoides) for Disease Prevention and Food Production

antioxidants Review Wide Spectrum of Active Compounds in Sea Buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides) for Disease Prevention and Food Production Agnieszka Ja´sniewska* and Anna Diowksz Institute of Fermentation Technology and Microbiology, Faculty of Biotechnology and Food Sciences, Lodz University of Technology (TUL), 171/173 Wólcza´nskaStreet, 90-924 Łód´z,Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Growing demand for value-added products and functional foods is encouraging manufac- turers to consider new additives that can enrich their products and help combat lifestyle diseases. The healthy properties of sea buckthorn have been recognized for centuries. This plant has a high content of bioactive compounds, including antioxidants, phytosterols, essential fatty acids, and amino acids, as well as vitamins C, K, and E. It also has a low content of sugar and a wide spectrum of volatiles, which contribute to its unique aroma. Sea buckthorn shows antimicrobial and antiviral properties, and is a potential nutraceutical or cosmeceutical. It was proven to help treat cardiovascular disease, tumors, and diabetes, as well as gastrointestinal and skin problems. The numerous health benefits of sea buckthorn make it a good candidate for incorporation into novel food products. Keywords: sea buckthorn; natural antioxidants; bioactive compounds; functional food; nutraceuticals Citation: Ja´sniewska,A.; Diowksz, A. Wide Spectrum of Active Compounds in Sea Buckthorn (Hippophae 1. Introduction rhamnoides) for Disease Prevention and Food Production. Antioxidants Sea buckthorn is a plant native to China and is found throughout the major temperate 2021, 10, 1279. https://doi.org/ zones of the world, including France, Russia, Mongolia, India, Great Britain, Denmark, 10.3390/antiox10081279 the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, Finland, and Norway [1].