Frangula Alnus P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Systematikss11 8.Pdf

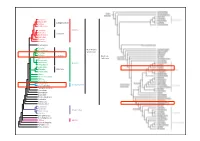

Asterales Dipsacales Campanulanae Apiales Aquifoliales Lamiales Asteridae Solanales Lamianae Gentianales Garryales Ericales Cornales Saxifragales Fagales Kern-Eudico- Cucurbitales tyledoneae Rosales Fabales Fabanae Eudicoty- Zygophyllales ledoneae Celastrales Oxalidales Rosidae Malpighiales Sapindales Malvales Malvanae Brassicales Vitales Crossosomatales Myrtales Geraniales Polygonales Caryophyllidae Caryophyllales Berberidopsidales Santalales Gunnerales Buxaceae Trochodendrales Proteales Sabiaceae Ranunculales Canellales Piperales Magnoliidae Magnoliales Laurales Chloanthaceae Ceratophyllaceae Liliidae Liliidae Austrobaileyales Nymphaeales Amborellales Klasse: Magnoliopsida (Angiospermae) Dicotyledoneae, Zweikeimblättrige Ordnung: Rosales Familie: Rhamnaceae (Kreuzdorngewächse) Merkmale: – Holzpflanzen mit wechselständigen oder gegenständigen, ungeteilten Blättern mit krautigen oder dornigen Nebenblättern – radiäre, kleine, gelblich-grüne, meist zwittrige Blüten – meist 5-zählige, selten 4-zählige Blüten – epipetal (= vor den Kronblättern stehende) Staubblätter – intrastaminaler Diskus – Perianth perigyn = mittelständiger Fruchtknoten, selten unterständig – Steinfrüchte, Nussfrüchte oder Spaltfrüchte Klasse: Magnoliopsida (Angiospermae) Dicotyledoneae, Zweikeimblättrige Ordnung: Rosales Familie: Rhamnaceae (Kreuzdorngewächse) Rhamnus frangula = Frangula alnus (Faulbaum) Kelchblatt Kronblatt Merkmale: – 5-zählige Blüte Staubblatt – Rinde mit grauweißen Korkwarzen (= Lentizellen) – Blätter elliptisch-eiförmig, ganzrandig – beerenähnliche -

Invasion of Transition Hardwood Forests by Exotic Rhamnus Frangula: Chronology and Site Requirements

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Spring 2007 Invasion of transition hardwood forests by exotic Rhamnus frangula: Chronology and site requirements Hanna S. Wingard University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Wingard, Hanna S., "Invasion of transition hardwood forests by exotic Rhamnus frangula: Chronology and site requirements" (2007). Master's Theses and Capstones. 286. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/286 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INVASION OF TRANSITION HARDWOOD FORESTS BY EXOTIC RHAMNUS FRANGULA: CHRONOLOGY AND SITE REQUIREMENTS BY HANNA S. WINGARD Baccalaureate Degree, University of Michigan, 2000 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of M aster of Science in Natural Resources May, 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1443642 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Glossy Buckthorn Rhamnusoriental Frangula Bittersweet / Frangula Alnus Control Guidelines Fact Sheet

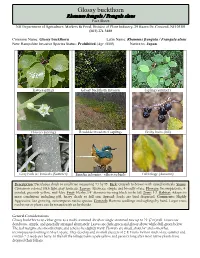

Glossy buckthorn Oriental bittersweet Rhamnus frangula / Frangula alnus Control Guidelines Fact Sheet NH Department of Agriculture, Markets & Food, Division of Plant Industry, 29 Hazen Dr, Concord, NH 03301 (603) 271-3488 Common Name: Glossy buckthorn Latin Name: Rhamnus frangula / Frangula alnus New Hampshire Invasive Species Status: Prohibited (Agr 3800) Native to: Japan leaves (spring) Glossy buckthorn invasion Sapling (summer) Flowers (spring) Roadside invasion of saplings Fleshy fruits (fall) Gray bark w/ lenticels (Summer) Emodin in berries - effects to birds Fall foliage (Autumn) Description: Deciduous shrub or small tree measuring 20' by 15'. Bark: Grayish to brown with raised lenticels. Stems: Cinnamon colored with light gray lenticels. Leaves: Alternate, simple and broadly ovate. Flowers: Inconspicuous, 4- petaled, greenish-yellow, mid-May. Fruit: Fleshy, 1/4” diameter turning black in the fall. Zone: 3-7. Habitat: Adapts to most conditions including pH, heavy shade to full sun. Spread: Seeds are bird dispersed. Comments: Highly Aggressive, fast growing, outcompetes native species. Controls: Remove seedlings and saplings by hand. Larger trees can be cut or plants can be treated with an herbicide. General Considerations Glossy buckthorn can either grow as a multi-stemmed shrub or single-stemmed tree up to 23’ (7 m) tall. Leaves are deciduous, simple, and generally arranged alternately. Leaves are dark-green and glossy above while dull-green below. The leaf margins are smooth/entire and tend to be slightly wavy. Flowers are small, about ¼” and somewhat inconspicuous forming in May to June. They develop and in small clusters of 2-8. Fruits form in mid to late summer and contain 2-3 seeds per berry. -

Biology of a Rust Fungus Infecting Rhamnus Frangula and Phalaris Arundinacea

Biology of a rust fungus infecting Rhamnus frangula and Phalaris arundinacea Yue Jin USDA-ARS Cereal Disease Laboratory University of Minnesota St. Paul, MN Reed canarygrass (Phalaris arundinacea) Nature Center, Roseville, MN Reed canarygrass (Phalaris arundinacea) and glossy buckthorn (Rhamnus frangula) From “Flora of Wisconsin” Ranked Order of Terrestrial Invasive Plants That Threaten MN -Minnesota Terrestrial Invasive Plants and Pests Center Puccinia coronata var. hordei Jin & Steff. ✧ Unique spore morphology: ✧ Cycles between Rhamnus cathartica and grasses in Triticeae: o Hordeum spp. o Secale spp. o Triticum spp. o Elymus spp. ✧ Other accessory hosts: o Bromus tectorum o Poa spp. o Phalaris arundinacea Rust infection on Rhamnus frangula Central Park Nature Center, Roseville, MN June 2017 Heavy infections on Rhamnus frangula, but not on Rh. cathartica Uredinia formed on Phalaris arundinacea soon after mature aecia released aeiospores from infected Rhamnus frangula Life cycle of Puccinia coronata from Nazaredno et al. 2018, Molecular Plant Path. 19:1047 Puccinia coronata: a species complex Forms Telial host Aecial host (var., f. sp.) (primanry host) (alternate host) avenae Oat, grasses in Avenaceae Rhamnus cathartica lolii Lolium spp. Rh. cathartica festucae Fescuta spp. Rh. cathartica hoci Hocus spp. Rh. cathartica agronstis Agrostis alba Rh. cathartica hordei barley, rye, grasses in triticeae Rh. cathartica bromi Bromus inermis Rh. cathartica calamagrostis Calamagrostis canadensis Rh. alnifolia ? Phalaris arundinacea Rh. frangula Pathogenicity test on cereal crop species using aeciospores from Rhamnus frangula Cereal species Genotypes Response Oats 55 Immune Barley 52 Immune Wheat 40 Immune Rye 6 Immune * Conclusion: not a pathogen of cereal crops Pathogenicity test on grasses Grass species Genotypes Response Phalaris arundinacea 12 Susceptible Ph. -

FLORA from FĂRĂGĂU AREA (MUREŞ COUNTY) AS POTENTIAL SOURCE of MEDICINAL PLANTS Silvia OROIAN1*, Mihaela SĂMĂRGHIŢAN2

ISSN: 2601 – 6141, ISSN-L: 2601 – 6141 Acta Biologica Marisiensis 2018, 1(1): 60-70 ORIGINAL PAPER FLORA FROM FĂRĂGĂU AREA (MUREŞ COUNTY) AS POTENTIAL SOURCE OF MEDICINAL PLANTS Silvia OROIAN1*, Mihaela SĂMĂRGHIŢAN2 1Department of Pharmaceutical Botany, University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Tîrgu Mureş, Romania 2Mureş County Museum, Department of Natural Sciences, Tîrgu Mureş, Romania *Correspondence: Silvia OROIAN [email protected] Received: 2 July 2018; Accepted: 9 July 2018; Published: 15 July 2018 Abstract The aim of this study was to identify a potential source of medicinal plant from Transylvanian Plain. Also, the paper provides information about the hayfields floral richness, a great scientific value for Romania and Europe. The study of the flora was carried out in several stages: 2005-2008, 2013, 2017-2018. In the studied area, 397 taxa were identified, distributed in 82 families with therapeutic potential, represented by 164 medical taxa, 37 of them being in the European Pharmacopoeia 8.5. The study reveals that most plants contain: volatile oils (13.41%), tannins (12.19%), flavonoids (9.75%), mucilages (8.53%) etc. This plants can be used in the treatment of various human disorders: disorders of the digestive system, respiratory system, skin disorders, muscular and skeletal systems, genitourinary system, in gynaecological disorders, cardiovascular, and central nervous sistem disorders. In the study plants protected by law at European and national level were identified: Echium maculatum, Cephalaria radiata, Crambe tataria, Narcissus poeticus ssp. radiiflorus, Salvia nutans, Iris aphylla, Orchis morio, Orchis tridentata, Adonis vernalis, Dictamnus albus, Hammarbya paludosa etc. Keywords: Fărăgău, medicinal plants, human disease, Mureş County 1. -

Seed Dormancy and Consequences for Direct Tree Seeding H

Seed dormancy and consequences for direct tree seeding H. Frochot, Philippe Balandier, A. Sourisseau To cite this version: H. Frochot, Philippe Balandier, A. Sourisseau. Seed dormancy and consequences for direct tree seed- ing. Final COST E47 conference Forest vegetation management towards environmental sustainability, May 2009, Vejle, Denmark. p. 43 - p. 45. hal-00468732 HAL Id: hal-00468732 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00468732 Submitted on 31 Mar 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Forest Vegetation Management – towards environmental sustainability, N.S. Bentsen (Ed.), Proccedings from the final COST E47 Conference, Vejle, Denmark, 2009/05/5-7, Forest and Landscape Working Papers n° 35-2009, 43-45. Seed dormancy and consequences for direct tree seeding Henri Frochot1), Philippe Balandier2,3), Agnès Sourisseau4) 1) INRA, UMR1092 LERFOB, F-54280 Champenoux, France, [email protected]; [email protected] 2) Cemagref, UR EFNO, Nogent sur Vernisson, France 3) INRA, UMR547 PIAF, Clermont-Ferrand, France 4) Independent Landscaper, Paris, France Key words Afforestation, direct seeding, dormancy, seed, tree Introduction Whereas direct tree seeding was probably used extensively in France in the past, it is currently only employed for the reforestation of Pinus pinaster and some species with big seeds such as oak. -

Frangula Paruensis, a New Name for Rhamnus Longipes Steyermark (Rhamnaceae)

FRANGULA PARUENSIS, A NEW NAME FOR RHAMNUS LONGIPES STEYERMARK (RHAMNACEAE) GERARDO A. AYMARD C.1, 2 Abstract. The new name Frangula paruensis (Rhamnaceae) is proposed to replace the illegitimate homonym Rhamnus longipes Steyermark (1988). Chorological, taxonomic, biogeographical, and habitat notes about this taxon also are provided. Resumen. Se propone Frangula paruensis (Rhamnaceae) como un nuevo nombre para reemplazar el homónimo ilegítimo Rhamnus longipes Steyermark (1988). Se incluye información corológica, taxonómica, biogeográfica, y de hábitats acerca de la especie. Keywords: Frangula, Rhamnus, Rhamnaceae, Parú Massif, Tepuis flora, Venezuela Rhamnus L. and Frangula Miller (Rhamnaceae) have Frangula paruensis is a shrub, ca. 2 m tall, with leaves ca. 150 and ca. 50 species, respectively (Pool, 2013, 2015). ovate, or oblong-ovate, margin subrevolute, repand- These taxa are widely distributed around the world but are crenulate, a slightly elevated tertiary venation on the lower absent in Madagascar, Australia, and Polynesia (Medan and surface, and mature fruiting peduncle and pedicels 1–1.5 Schirarend, 2004). According to Grubov (1949), Kartesz cm long, and fruiting calyx lobes triangular-lanceolate and Gandhi (1994), Bolmgren and Oxelman (2004), and (two main features to separate Frangula from Rhamnus). Pool (2013) the recognition of Frangula is well supported. This species is endemic to the open, rocky savannas On the basis of historical and recent molecular work the on tepui slopes and summits at ca. 2000 m (Steyermark genus is characterized by several remarkable features. Pool and Berry, 2004). This Venezuelan taxon was described (2013: 448, table 1) summarized 11 features to separate the as Rhamnus longipes by Steyermark (1988), without two genera. -

Herb Other Names Re Co Rde D Me Dicinal Us E Re

RECORDED USE RECORDED USE MEDICINAL US AROMATHERA IN COSMETICS IN RECORDED RECORDED FOOD USE FOOD IN Y E P HERB OTHER NAMES COMMENTS Parts Used Medicinally Abelmoschus moschatus Hibiscus abelmoschus, Ambrette, Musk mallow, Muskseed No No Yes Yes Abies alba European silver fir, silver fir, Abies pectinata Yes No Yes Yes Leaves & resin Abies balsamea Balm of Gilead, balsam fir Yes No Yes Yes Leaves, bark resin & oil Abies canadensis Hemlock spruce, Tsuga, Pinus bark Yes No No No Bark Abies sibirica Fir needle, Siberian fir Yes No Yes Yes Young shoots This species not used in aromatherapy but Abies Sibirica, Abies alba Miller, Siberian Silver Fir Abies spectabilis Abies webbiana, Himalayan silver fir Yes No No No Essential Oil are. Leaves Aqueous bark extract which is often concentrated and dried to produce a flavouring. Distilled with Extract, bark, wood, Acacia catechu Black wattle, Black catechu Yes Yes No No vodka to make Blavod (black vodka). flowering tops and gum Acacia farnesiana Cassie, Prickly Moses Yes Yes Yes Yes Ripe seeds pressed for cooking oil Bark, flowers Source of Gum Arabic (E414) and Guar Gum (E412), controlled miscellaneous food additive. Used Acacia senegal Guar gum, Gum arabic No Yes No Yes in foods as suspending and emulsifying agent. Acanthopanax senticosus Kan jang Yes No No No Kan Jang is a combination of Andrographis Paniculata and Acanthopanax Senticosus. Flavouring source including essential oil. Contains natural toxin thujone/thuyone whose levels in flavourings are limited by EU (Council Directive 88/388/EEC) and GB (SI 1992 No.1971) legislation. There are several chemotypes of Yarrow Essential Oil, which is steam distilled from the dried herb. -

Rhamnaceae) Jürgen Kellermanna,B

Swainsona 33: 43–50 (2020) © 2020 Board of the Botanic Gardens & State Herbarium (Adelaide, South Australia) Nomenclatural notes and typifications in Australian species of Paliureae (Rhamnaceae) Jürgen Kellermanna,b a State Herbarium of South Australia, GPO Box 1047, Adelaide, South Australia 5001 Email: [email protected] b The University of Adelaide, School of Biological Sciences, Adelaide, South Australia 5005 Abstract: The nomenclature of the four species of Ziziphus Mill. and the one species of Hovenia Thunb. occurring in Australia is reviewed, including the role of the Hermann Herbarium for the typification of Z. oenopolia (L.) Mill. and Z. mauritiana Lam. Lectotypes are chosen for Z. quadrilocularis F.Muell. and Z. timoriensis DC. A key to species is provided, as well as illustrations for Z. oenopolia, Z. quadrilocularis and H. dulcis Thunb. Keywords: Nomenclature, typification, Hovenia, Ziziphus, Rhamnaceae, Paliureae, Paul Hermann, Carolus Linnaeus, Henry Trimen, Australia Introduction last worldwide overview of the genus was published by Suessenguth (1953). Since then, only regional Rhamnaceae tribe Paliureae Reissek ex Endl. was treatments and revisions have been published, most reinstated by Richardson et al. (2000b), after the first notably by Johnston (1963, 1964, 1972), Bhandari & molecular analysis of the family (Richardson et al. Bhansali (2000), Chen & Schirarend (2007) and Cahen 2000a). It consists of three genera, Hovenia Thunb., et al. (in press). For Australia, the genus as a whole was Paliurus Tourn. ex Mill. and Ziziphus Mill., which last reviewed by Bentham (1863), with subsequent until then were assigned to the tribes Rhamneae regional treatments by Wheeler (1992) and Rye (1997) Horan. -

Section 317.1A (16, 2)

1 WEEDS, §317.1A 317.1A Noxious weeds. 1. The following weeds are hereby declared to be noxious and shall be divided into two classes, as follows: a. Primary noxious weeds, which shall include: (1) Quack grass (Elymus repens). (2) Perennial sow thistle (Sonchus arvensis). (3) Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense). (4) Bull thistle (Cirsium vulgare). (5) European morning glory or field bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis). (6) Horse nettle (Solanum carolinense). (7) Leafy spurge (Euphorbia esula). (8) Perennial pepper-grass (Cardaria draba). (9) Russian knapweed (Acroptilon repens). (10) Buckthorn (Rhamnus spp., not to include Frangula alnus, syn. Rhamnus frangula). (11) All other species of thistles belonging in the genera of Cirsium and Carduus. (12) Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri). b. Secondary noxious weeds, which shall include: (1) Butterprint (Abutilon theophrasti) annual. (2) Cocklebur (Xanthium strumarium) annual. (3) Wild mustard (Sinapis arvensis) annual. (4) Wild carrot (Daucus carota) biennial. (5) Buckhorn (Plantago lanceolata) perennial. (6) Sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella) perennial. (7) Sour dock (Rumex crispus) perennial. (8) Smooth dock (Rumex altissimus) perennial. (9) Poison hemlock (Conium maculatum). (10) Multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora). (11) Wild sunflower (wild strain of Helianthus annuus L.) annual. (12) Puncture vine (Tribulus terrestris) annual. (13) Teasel (Dipsacus spp.) biennial. (14) Shattercane (Sorghum bicolor) annual. 2. a. The multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora) shall not be considered a secondary noxious weed when cultivated for or used as understock for cultivated roses or as ornamental shrubs in gardens, or in any county whose board of supervisors has by resolution declared it not to be a noxious weed. b. Shattercane (Sorghum bicolor) shall not be considered a secondary noxious weed when cultivated or in any county whose board of supervisors has by resolution declared it not to be a noxious weed. -

(GISD) 2021. Species Profile Ziziphus Mauritiana. Availab

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Ziziphus mauritiana Ziziphus mauritiana System: Terrestrial Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Plantae Magnoliophyta Magnoliopsida Rhamnales Rhamnaceae Common name appeldam (English, Dutch West Indies), baher (English, Fiji), bahir (English, Fiji), baer (English, Fiji), jujube (English, Guam), manzanita (English, Guam), manzanas (English, Guam), jujubier (French), Chinese date (English), Chinese apple (English), Indian jujube (English), Indian plum (English), Indian cherry (English), Malay jujube (English), coolie plum (English, Jamaica), crabapple (English, Jamaica), dunk (English, Barbados), mangustine (English, Barbados), dunks (English, Trinidad), dunks (English, Tropical Africa), Chinee apple (English, Queensland, Australia), ponsigne (English, Venezuela), yuyubo (English, Venezuela), aprin (English, Puerto Rico), yuyubi (English, Puerto Rico), perita haitiana (English, Dominican Republic), pomme malcadi (French, West Indies), pomme surette (French, West Indies), petit pomme (French, West Indies), liane croc chien (French, West Indies), gingeolier (French, West Indies), dindoulier (French, West Indies), manzana (apple) (English, Philippines), manzanita (little apple) (English, Philippines), bedara (English, Malaya), widara (English, Indonesia), widara (English, Surinam), phutsa (English, Thailand), ma-tan (English, Thailand), putrea (English, Cambodia), tao (English, Vietnam), tao nhuc (English, Vietnam), ber (English, India), bor (English, India) Synonym Ziziphus jujuba , (L.) Lam., non P. Mill. Rhamnus mauritiana -

NRM Plan Italian Buckthorn (Rhamnus Alaternus) CONTACT Reducing Its Impact in the Northern and Yorke NRM Region

Government of South Australia Northern and Yorke Natural FACT SHEET NO. 1.020 Resources Management Board June 2011 NRM Plan Italian buckthorn (Rhamnus alaternus) CONTACT Reducing its impact in the Northern and Yorke NRM Region Main Office Description of this weed Northern and Yorke NRM Board Buckthorn is a 3-5 metre tall small shrub PO Box 175 with bright green leathery leaves which 41-49 Eyre Road are lance-oval shape, with finely serrated Crystal Brook SA 5523 margins. The leaf’s upper surface is bright Ph: (08) 8636 2361 green, with the underside being paler Fx: (08) 8636 2371 in colour. www.nynrm.sa.gov.au The stems are smooth, not thorny as its common name suggests. Flowers are small, 3-4mm in diameter, with 5 petals and are yellow-green in colour. Flowering occurs in winter to early spring. Fruits are round, egg-shaped berries, smooth, 5-7mm long, red ripening to black. Buckthorn is generally found in areas receiving greater than 500mm of rain. Why is it a weed and what is the impact? Buckthorn was introduced to Australia as a garden plant and has escaped into Buckthorn is spread by birds eating the the bush. It is a hardy plant that will fruit and dispersing the seeds. Foxes and grow in a variety of soil types including possums also have the potential to spread riparian environments, sand dunes and the seeds. It suckers freely from a base escarpments. It tolerates full sun, cold and or roots, especially from inappropriately seasonal dry spells. dumped garden waste.