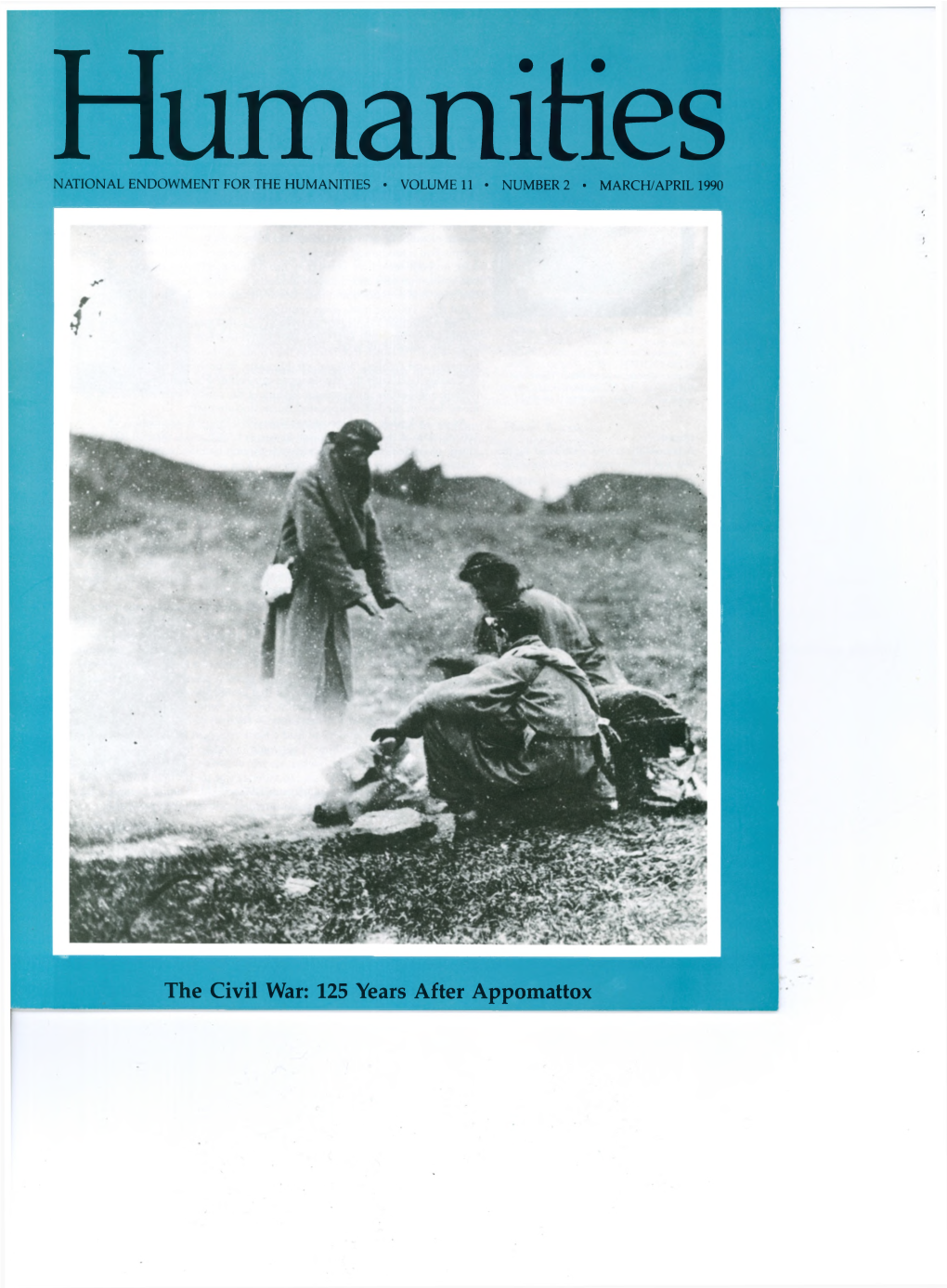

The Civil War: 125 Years After Appomattox Editor's Note

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to loe removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI* Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 WASHINGTON IRVING CHAMBERS: INNOVATION, PROFESSIONALIZATION, AND THE NEW NAVY, 1872-1919 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctorof Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Stephen Kenneth Stein, B.A., M.A. -

“What Are Marines For?” the United States Marine Corps

“WHAT ARE MARINES FOR?” THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation by MICHAEL EDWARD KRIVDO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2011 Major Subject: History “What Are Marines For?” The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era Copyright 2011 Michael Edward Krivdo “WHAT ARE MARINES FOR?” THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation by MICHAEL EDWARD KRIVDO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Joseph G. Dawson, III Committee Members, R. J. Q. Adams James C. Bradford Peter J. Hugill David Vaught Head of Department, Walter L. Buenger May 2011 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT “What Are Marines For?” The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era. (May 2011) Michael E. Krivdo, B.A., Texas A&M University; M.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Joseph G. Dawson, III This dissertation provides analysis on several areas of study related to the history of the United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era. One element scrutinizes the efforts of Commandant Archibald Henderson to transform the Corps into a more nimble and professional organization. Henderson's initiatives are placed within the framework of the several fundamental changes that the U.S. Navy was undergoing as it worked to experiment with, acquire, and incorporate new naval technologies into its own operational concept. -

Descendants of George Fulp

Descendants of George Fulp Generation 1 1. GEORGE1 FULP was born in 1718 in Heidelberg, Germany. He died on 26 Oct 1786 in Belews Creek, Surry, NC. He married MARY H PHILLIPS in 1752. She was born in 1722 in Berks, PA. She died in 1800 in Stokes County, NC. Notes for George Fulp: On September, Wednesday, the 25th, 1751, the ship Phoenix, John Suprrier, Captain, arrived in Philadelphia, Pa., from Rotterdam, the Neitherlands, via Portsmouth, England with 412 passengers. One of the passengers was Georg Volpp (pronounced Gay-org Folp). It is thought that Georg Volpp became our George Fulp. It was common to change German and other European names to names that were easier to spell and pronounce in English. Also, names were changed to "fit in" and possibly avoid secular conflicts that were common at this time. A director at the Moravian Archive in Winston Salem, North Carolina, advises that the German name Volpp is easily translated to Fulp. Also, another passenger on the same ship was Jacob Koehler. There are some indications that this person eventually settled in the Stokes County, North Carolina area near George Fulp. At George Fulps' request, a John Jacob Koehler (a Moravian Bishop) held his funeral services. After landing in Pennsylvania, George Fulp settled in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. In 1752, he married Mary H. Phillips who was born in 1714 in Exeter, Berks County, Pennsylvania. They had five children. In the early 1760s, George moved his family to Stokes County, North Carolina about 15 miles north of what is now Winston-Salem in Forsyth County. -

How the Civil War Civilized Seattle

How the Civil War Civilized Seattle The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:37736798 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA How the Civil War Civilized Seattle Paul B. Hagen A Thesis in the Field of History for a Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University November 2017 Copyright 2017 Paul B. Hagen Abstract Founded in 1851, Seattle was little more than a rough-and-tumble frontier town at the onset of the Civil War. However, by 1880 the young community had developed into a small, but prosperous city. Not only did the population grow immensely during this time, but the character of the town also changed. By 1880 Seattle was no longer just another western logging town, but rather a civilized metropolitan center. Although the rapid development of Seattle is widely accepted, the connection between it and the Civil War has not been reported. Historical data suggest that the Civil War did influence the development of Seattle. The Civil War caused Seattle’s population to grow through recruitment of unemployed war widows and orphans. These recruits brought New England culture to Seattle, which served as a civilizing force. The Civil War also led to policies that helped Seattle develop in other ways. -

Fort Dupont Park Historic Resources Study Final Robinson & Associates

Fort Dupont Park Historic Resources Study Final Robinson & Associates, Inc. November 1, 2004 Page 1 ______________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS I. LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 2 II. PURPOSE AND METHODOLOGY 5 III. SUMMARY OF SIGNIFICANCE 6 IV. HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT 20 1. Pre-Civil War History 20 2. 1861-65: The Civil War and Construction of Fort Dupont 25 3. Post-Civil War Changes to Washington and its Forts 38 4. The Planning and Construction of the Fort Drive 48 5. Creation of Fort Dupont Park 75 6. 1933-42: The Civilian Conservation Corps Camp at Fort Dupont Park 103 7. 1942-45: Antiaircraft Artillery Command Positioned in Fort Dupont Park 116 8. History of the Golf Course 121 9. 1938 through the 1970s: Continued Development of Fort Dupont Park 131 10. Recreational, Cultural, and African-American Family Use of Fort Dupont Park 145 11. Proposals for the Fort Circle Parks 152 12. Description of Fort Dupont Park Landscape Characteristics, Buildings and Structures 155 V. BIBLIOGRAPHY 178 VI. KEY PARK LEGISLATION 191 Fort Dupont Park Historic Resources Study Final Robinson & Associates, Inc. November 1, 2004 Page 2 ______________________________________________________________________________________ I. LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1 Fort Dupont Park is located in the southeast quadrant of Washington, D.C. 7 Figure 2 Fort Dupont Park urban context, 1995 8 Figure 3 Map of current Fort Dupont Park resources 19 Figure 4 Detail of the 1856-59 Boschke Topographical Map 24 Figure 5 Detail -

Volume 27 , Number 2

THE HUDSON RIVER VALLEY REVIEW A Journal of Regional Studies The Hudson River Valley Institute at Marist College is supported by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Publisher Thomas S. Wermuth, Vice President for Academic Affairs, Marist College Editors Christopher Pryslopski, Program Director, Hudson River Valley Institute, Marist College Reed Sparling, Writer, Scenic Hudson Mark James Morreale, Guest Editor Editorial Board The Hudson River Valley Review Myra Young Armstead, Professor of History, (ISSN 1546-3486) is published twice Bard College a year by the Hudson River Valley Institute at Marist College. COL Lance Betros, Professor and Head, Department of History, U.S. Military James M. Johnson, Executive Director Academy at West Point Research Assistants Kim Bridgford, Professor of English, Gabrielle Albino West Chester University Poetry Center Gail Goldsmith and Conference Amy Jacaruso Michael Groth, Professor of History, Wells College Brian Rees Susan Ingalls Lewis, Associate Professor of History, State University of New York at New Paltz Hudson River Valley Institute Advisory Board Sarah Olson, Superintendent, Roosevelt- Peter Bienstock, Chair Vanderbilt National Historic Sites Margaret R. Brinckerhoff Roger Panetta, Professor of History, Dr. Frank Bumpus Fordham University Frank J. Doherty H. Daniel Peck, Professor of English, BG (Ret) Patrick J. Garvey Vassar College Shirley M. Handel Robyn L. Rosen, Associate Professor of History, Marjorie Hart Marist College Maureen Kangas Barnabas McHenry David Schuyler, -

A Commemorative Program of the Distinguished Women of North

jLai The Nortft Carodna Council for Women ^ ^ -^ N.C.DOCUMt- Presents clearinshouse Women ofthe Century APR ^ 7 2000 STATEUBRARY OF NORTH mQudr\ RALEIGH l^mr -nmi Distifi^uJ5fxc<f Women Awonfc Banquet Commemorative Program Moirfi 14, 2000 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from State Library of North Carolina http://www.archive.org/details/womenofcenturyco2000 Women ofific Century (A commemorative program, ofihc Distinguished Women ofNortfi Caro&na Awards Banquet) Governor James B. Hunt Jr. Secretary Katie G. Dorsett North Carolina Department of Administration Juanita M. Bryant, Executive Director North Carolina Council for Women This publication was made possible by a grant from Eli Lilly and Company. Nortfi CaroGna Women in State Qovemment cs Women Currently Serving in Top Level State Government Positions Elaine Marshall, Secretary of State Katie Dorset!, Betty McCain, Secretary, Secretary, Department of Department of Administration Cultural Resources afc_j£. Janice Faulkner, Former Secretary of Muriel Offerman, Revenue and Secretary, Current Department of Commissioner, Revenue Division of Motor Vehicles Justice Sarah Parker, State Supreme Court Current Female Legislators 1999-2000 Row 1 (l-r): Rep. Alma S. Adams, Rep. Martha B. Alexander, Rep. Cherie K. Berry, Rep. Joanne W. Bowie, ^ Rep. Flossie Boyd-IVIclntyre, Rep. Debbie A. Clary, Sen. Betsy L. Coctirane Row 2 (l-r): Rep. Beverly M. Earle, Rep. Ruth Easterling, Rep. Theresa H. Esposito, Sen. Virginia Foxx, Rep. Charlotte A. Gardner, Sen. Linda Garrou, Sen. Kay R. Hagan Row 3 (l-r): Rep. Julia C. Howard, Rep. Veria C. Insko, Rep. Mary L. Jarrell, Rep. Margaret M. "Maggie" Jeffus, Sen. Eleanor Kinnaird, Sen. -

Calvert County Sheriff's Office 2014 Annual Report Table of Contents

CALVERT COUNTY SHERIFF'S OFFICE 2014 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS Messages ..................................................................................................2 Sheriff ...........................................................................................................................2 Assistant Sheriff ........................................................................................................3 Detention Center Administrator ........................................................................3 Detention Center Deputy Administrator ........................................................4 Calvert County Sheriff’s Office ..........................................................5 History .........................................................................................................................5 Community Profile ..................................................................................................6 Office of Professional Standards ......................................................7 Administrative & Judicial Services Bureau ...................................8 Civil Process ...............................................................................................................8 Courthouse Security ...............................................................................................9 Southern Maryland Criminal Justice Academy .............................................9 Animal Control Unit ..............................................................................................10 -

Sons of the American Revolution Will Be Held at Toledo, Ohio, Fee S Company Mass

OFFICIAL BULLP:TIN EDWARD ROYAL_ SORBER, Germantown, Pa. (21437). Great•-grands Adam Ohl, pnvate, Col. William Bradford's Philadelphia Regt pon of Militia. · enna. OFFICIAL BULLETIN GEORGE HOMER SPALDING, Lowell, Mass. (21476). Great•-grandson of 01' Nicholas Cooke, Governor of Rhode Island, 1775-1778. ROLLIN AARON SPALDING, Lynn, Mass. (21481). Great-grandson of R b THE NATIONAL SOCIETY 0 Spalding, Second Lieutenant Fourth Middlesex County Regt. Mass M. ~rt 11 gran d son o f R o bert S f>a 1dmg, · Jr., private, Captain Ballard's Company· C 1'ha '· 01' THe: Whitcomb'• Mass. Regt. • 0 one! FRANCIS HERBERT STEVENS, Wellesley, Mass. (21483). Great'-grandson , 0 OF THE Ephra•m Ste1.•ens, Sergeant of Minute Men, Col. Aaron Davis's Mass. Regt. ' SONS AMERICAN REVOLUTION CHARLES EDWIN SUTTON, East Providence, R. I. (2o67o). Great-grandson President General Organized April 30, 1889 of. R~~crt Sutt.on, Sergeant, Col. Timothy Walker's Mass. Regt., sailor M Morris B. Bea1dsley, Bridaeport, Conn. Incorporated by Act ol Conaresa June 9, 1906 Sh1p Eagle" m 1780. ass. JOHN NORTHRU~ THURLOW, Brooklyn, N. Y. (21330). Great"-grandso f MARCH, 1910 Number 4 0 Volume IV G~d Talcott, pnvate Conn. Militia; great•-grandson of Peter Bonticon ~ ta1n of Barque "Hawk," prisoner on "Jers~y" prison-ship. ' ap- Publiahed at the office of the Secretary General (A. Howard Clark, Smithaonian GEORGE WINTHROP. TOPPAN, Fairfield, Me. (2o965). Great•-~randson of (aotitution), Waahin~rton, D. C., in May, October, December, and March. Samuel P•llsbury, pnvate, Capt. Richard Titcomb's Company, Colonel w d , Entered as second-class matter, May 7, Igo8, at the post-office at Washington, Mass. -

The Official Bulletin Attempts to Answer These Questions As It Recounts the IATSE’S One-Of-A-Kind History

EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Matthew D. Loeb James B. Wood International President General Secretary–Treasurer Thomas C. Short Edward C. Powell International President Emeritus International Vice President Emeritus Michael J. Barnes John M. Lewis 1st Vice President 7th Vice President Thom Davis Craig Carlson 2nd Vice President 8th Vice President Damian Petti Phil S. Locicero 3rd Vice President 9th Vice President Michael F. Miller, Jr. C. Faye Harper 4th Vice President 10th Vice President Daniel Di Tolla Colleen A. Glynn 5th Vice President 11th Vice President John R. Ford James J. Claffey, Jr. 6th Vice President 12th Vice President Joanne M. Sanders 13th Vice President TRUSTEES Patricia A. White Carlos Cota Andrew Oyaas CLC DELEGATE Siobhan Vipond FIND US ONLINE GENERAL COUNSEL Samantha Dulaney GENERAL OFFICE 207 West 25th Street, 4th Floor, New York, NY 10001 Visit us on the Web: www.iatse.net Tele: (212) 730-1770 FAX: (212) 730-7809 WEST COAST OFFICE 10045 Riverside Drive, Toluca Lake, CA 91602 Tele: (818) 980-3499 FAX: (818) 980-3496 IATSE: www.facebook.com/iatse CANADIAN OFFICE IATSE Canada: www.facebook.com/iatsecanada 22 St. Joseph St., Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4Y 1J9 Young Workers: www.facebook.com/groups/IATSEYWC Tele: (416) 362-3569 FAX: (416) 362-3483 WESTERN CANADIAN OFFICE 1000-355 Burrard St., Vancouver, British Columbia V6C 2G8 IATSE: @iatse Tele: (604) 608-6158 FAX: (778) 331-8841 IATSE Canada: @iatsecanada CANADIAN ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY Young Workers: @iatseywc RETIREMENT PLAN 22 St. Joseph St., Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4Y 1J9 Tele: (416) 362-2665 FAX: (416) 362-2351 www.ceirp.ca IATSE: www.instagram.com/iatse I.A.T.S.E. -

White Slaves in Barbary: the Early American Republic, Orientalism and the Barbary Pirates

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Vanderbilt Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Archive White Slaves in Barbary: The Early American Republic, Orientalism and the Barbary Pirates By Angela Sutton Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History May, 2009 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor Jane Landers Professor Katherine Crawford “In this work, I have most attempted a full description of the many hellish torments and punishments those piratical sea-rovers invent and inflict on the unfortunate Christians who may by chance unhappily fall into their hands…”38 wrote John Foss, an American sailor captured by pirates off the coast of North Africa and sold into slavery in 1793. Many other captives were not as reserved, describing the pirate’s bloody attacks with colorful, titillating language that provoked outrage in early America. Although often exaggerated or forged, the Orientalist stereotypes perpetuated about the Barbary Pirates by captives like John Foss would resonate in the minds of early Americans and shape American foreign policy. These first encounters with North Africa through the pirates set a precedent for how the young nation would engage with belligerent powers in the future. While European superpowers paid tribute and appeased the Barbary nations in order to incapacitate their economic rivals on the seas, the American Congress commissioned a naval fleet and prepared for war. The language used in the accounts of the Barbary captives, in the colonial American newspapers, and by the founding fathers demonstrates that the legend of the Barbary pirates shaped American views of “the Orient,” which led to acceptance of aggressive foreign policy in the Mediterranean. -

BLACK PARENTAL PROTECTIONISM Jada Phelps Moultrie Submitted To

REFRAMING PARENTAL INVOLVEMENT OF BLACK PARENTS: BLACK PARENTAL PROTECTIONISM Jada Phelps Moultrie Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Education, Indiana University October 2016 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee May 1 1, 201 6 ii Dedication This is dedicated to all Black parents, specifically, the participants in this study, as well as my parents and my grandparents. Each name recalled in dedication, I have drawn my strength from and is how I got through this journey. I would specifically like to dedicate this work to Violet Hogan my fifth great paternal grandmother and my own mother, DiLynn Valerie Thomas Phelps, and father, Marcus Anthony Phelps I. My brother, Lil’ Marcus Anthony Phelps II, father of my nephew, Marcus III. In spirit Ruth and Elzie Phelps, parents of Michael and Morris Smitherman, Marcus, Marietta, Mitchell, and Molly Phelps; In spirit Pearl and Terrell Thomas I, parents of Edith, Terrell “Bro”, Marilyn, Kenneth, DiLynn, and Van Veen Thomas; Robin Khan, mother of Antoin Moultrie; and Antoin Mandel Moultrie, my husband and stepfather of my son Stephen Jaden Mosby, “Victorious Leader”, father of my son Andric Jasiri Moultrie, “Fearless Warrior” and father to my daughter, Alaira Janie Lynn Moultrie, “the Great Unifier and Beautiful Gift from God”. We are rich in family. Together we rise. iii Acknowledgments It is a rarity for me to feel inferior, particularly because I know that it was and arguably remains the primary weapon used to destroy people of color.