Fort Dupont Park Historic Resources Study Final Robinson & Associates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 NCBJ Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C. - Early Ideas Regarding Extracurricular Activities for Attendees and Guests to Consider

2019 NCBJ Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C. - Early Ideas Regarding Extracurricular Activities for Attendees and Guests to Consider There are so many things to do when visiting D.C., many for free, and here are a few you may have not done before. They may make it worthwhile to come to D.C. early or to stay to the end of the weekend. Getting to the Sites: • D.C. Sites and the Pentagon: Metro is a way around town. The hotel is four minutes from the Metro’s Mt. Vernon Square/7th St.-Convention Center Station. Using Metro or walking, or a combination of the two (or a taxi cab) most D.C. sites and the Pentagon are within 30 minutes or less from the hotel.1 Googlemaps can help you find the relevant Metro line to use. Circulator buses, running every 10 minutes, are an inexpensive way to travel to and around popular destinations. Routes include: the Georgetown-Union Station route (with a stop at 9th and New York Avenue, NW, a block from the hotel); and the National Mall route starting at nearby Union Station. • The Mall in particular. Many sites are on or near the Mall, a five-minute cab ride or 17-minute walk from the hotel going straight down 9th Street. See map of Mall. However, the Mall is huge: the Mall museums discussed start at 3d Street and end at 14th Street, and from 3d Street to 14th Street is an 18-minute walk; and the monuments on the Mall are located beyond 14th Street, ending at the Lincoln Memorial at 23d Street. -

Nehemiah Homes at Fort Dupont Planned Unit Development

202.942.5000 ARNOLD & PORTER 202.942.5999 Fax 555 Twelfth Street, NW Washington, DC 20004-1206 July 17, 2001 Ms. Carol Mitten, Chair District of Columbia Zoning Commission 441 4th Street, N.W. Suite 210 Washington, D.C. 20001 Re: Pre-Hearing Submission Zoning Commission Case No. Ol-12C Nehemiah Homes at Fort Dupont Planned Unit Development Dear Ms. Mitten and Members of the Commission: Pursuant to§ 3013 of the Rules of Practice and Procedure before the Zoning Commission, we are herewith submitting twenty (20) copies of the Pre-Hearing Submission on behalf of the applicant in the above-referenced case. This information includes the following items: 1. Twenty (20) copies of the original application booklet, modified in part to reflect more refined plans. 2. A list of witnesses who will testify at the public hearing, a summary of their testimony, and an estimate of the time required for the applicant's presentation. 3. Additional reports and plans, including: • Architectural Plans by Heffner Architects • Revised Site Plan by Ben Dyer and Associates • Traffic Impact Analysis Study by O.R. George & Associates, Inc. 4. Twenty (20) copies ofreduced plans and two (2) sets of full-size plans 5. As to the requirement in§ 3013.3 to name the property owners in the ~ase of a map amendment, no rezoning is proposed in this application. ZONING COMMISSION 6. Certification pursuant to § 3013.7: ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 01-12 ZONING COMMISSION Washington, DC New York Los Angeles Century City Denver London NorthernDistrict Virginia of Columbia CASE NO.01-12 EXHIBITDeletedEXHIBIT NO.16A1 NO.16 Ms. -

ROUTES LINE NAME Sunday Supplemental Service Note 1A,B Wilson Blvd-Vienna Sunday 1C Fair Oaks-Fairfax Blvd Sunday 2A Washington

Sunday Supplemental ROUTES LINE NAME Note Service 1A,B Wilson Blvd-Vienna Sunday 1C Fair Oaks-Fairfax Blvd Sunday 2A Washington Blvd-Dunn Loring Sunday 2B Fair Oaks-Jermantown Rd Sunday 3A Annandale Rd Sunday 3T Pimmit Hills No Service 3Y Lee Highway-Farragut Square No Service 4A,B Pershing Drive-Arlington Boulevard Sunday 5A DC-Dulles Sunday 7A,F,Y Lincolnia-North Fairlington Sunday 7C,P Park Center-Pentagon No Service 7M Mark Center-Pentagon Weekday 7W Lincolnia-Pentagon No Service 8S,W,Z Foxchase-Seminary Valley No Service 10A,E,N Alexandria-Pentagon Sunday 10B Hunting Point-Ballston Sunday 11Y Mt Vernon Express No Service 15K Chain Bridge Road No Service 16A,C,E Columbia Pike Sunday 16G,H Columbia Pike-Pentagon City Sunday 16L Annandale-Skyline City-Pentagon No Service 16Y Columbia Pike-Farragut Square No Service 17B,M Kings Park No Service 17G,H,K,L Kings Park Express Saturday Supplemental 17G only 18G,H,J Orange Hunt No Service 18P Burke Centre Weekday 21A,D Landmark-Bren Mar Pk-Pentagon No Service 22A,C,F Barcroft-South Fairlington Sunday 23A,B,T McLean-Crystal City Sunday 25B Landmark-Ballston Sunday 26A Annandale-East Falls Church No Service 28A Leesburg Pike Sunday 28F,G Skyline City No Service 29C,G Annandale No Service 29K,N Alexandria-Fairfax Sunday 29W Braeburn Dr-Pentagon Express No Service 30N,30S Friendship Hghts-Southeast Sunday 31,33 Wisconsin Avenue Sunday 32,34,36 Pennsylvania Avenue Sunday 37 Wisconsin Avenue Limited No Service 38B Ballston-Farragut Square Sunday 39 Pennsylvania Avenue Limited No Service 42,43 Mount -

Individual Projects

PROJECTS COMPLETED BY PROLOGUE DC HISTORIANS Mara Cherkasky This Place Has A Voice, Canal Park public art project, consulting historian, http://www.thisplacehasavoice.info The Hotel Harrington: A Witness to Washington DC's History Since 1914 (brochure, 2014) An East-of-the-River View: Anacostia Heritage Trail (Cultural Tourism DC, 2014) Remembering Georgetown's Streetcar Era: The O and P Streets Rehabilitation Project (exhibit panels and booklet documenting the District Department of Transportation's award-winning streetcar and pavement-preservation project, 2013) The Public Service Commission of the District of Columbia: The First 100 Years (exhibit panels and PowerPoint presentations, 2013) Historic Park View: A Walking Tour (booklet, Park View United Neighborhood Coalition, 2012) DC Neighborhood Heritage Trail booklets: Village in the City: Mount Pleasant Heritage Trail (2006); Battleground to Community: Brightwood Heritage Trail (2008); A Self-Reliant People: Greater Deanwood Heritage Trail (2009); Cultural Convergence: Columbia Heights Heritage Trail (2009); Top of the Town: Tenleytown Heritage Trail (2010); Civil War to Civil Rights: Downtown Heritage Trail (2011); Lift Every Voice: Georgia Avenue/Pleasant Plains Heritage Trail (2011); Hub, Home, Heart: H Street NE Heritage Trail (2012); and Make No Little Plans: Federal Triangle Heritage Trail (2012) “Mount Pleasant,” in Washington at Home: An Illustrated History of Neighborhoods in the Nation's Capital (Kathryn Schneider Smith, editor, Johns Hopkins Press, 2010) Mount -

DCPLUG ANC 3E Brief 4.11.19 FINAL

District of Columbia Power Line Undergrounding (DC PLUG) Initiative Presented to: ANC 3E Presented by: Anthony Soriano and Laisha Dougherty April 11, 2019 www.dcpluginfo.com Agenda • Background and History • Biennial Plan Feeder Locations • Feeder 308 Proposed Scope of Work • Customer Outreach • Contact Us 2 Background Background & Timeline Budget Aug 2012 Pepco Portion DC PLUG will provide resiliency The Mayor’s Power Line Undergrounding against major storms and improve the Task Force establishment $250 Million reliability of the electric system May 2013 * Recovered through Pepco The Task Force recommended Pepco and Underground Project Charge DDOTs partnership May 2014 District Portion The Electric Company Infrastructure $187.5 Million Improvement Financing Act became law Multi–year program to underground May 2017 * Recovered through Underground Rider up to 30 of the most vulnerable Council of the District of Columbia overhead distribution lines, spanning amended the law DDOT over 6-8 years with work beginning in July 2017 mid 2019 Pepco and DDOT filed a joint Biennial Plan up to $62.5 Million Nov 2017 DDOT Capital Improvement Funding Received Approval from D.C. Public Service Commission on the First Biennial Plan 3 Biennial Plan • In accordance with the Act, Pepco and DDOT filed a joint Biennial Plan on July 3, 2017 covering the two-year period, 2017-2019. The next Biennial Plan is planned to be filed September 2019. • Under the Biennial Plan, DDOT primarily will construct the underground facilities, and Pepco primarily will install -

Capital Bikeshare Proposed and Expanded Loactions

CAPITAL BIKESHARE PROPOSED AND EXPANDED LOCATIONS Beach North Rock Creek Parkway Portal W R E D EASTERN AVE S L T A T B R E O A P C BE H LO A C C D U H ST RD DR R Shepherd KA Field LM IA RD WISE RD Marvin Caplan TNUT Memorial Park CHES ST Pinehurst Parkway Piney Branch Portal BUTTERNUT ST WESTERN AVE ASPEN ST U OREGONAVE Takoma T Rec A Fort B N H H Stevens L E A A Takoma Community I V V R Center A E D R Lafayette Lamond Chevy A D Chase A Circle V E 3RD ST 14THST 5TH ST 5TH Chevy Chase Community Center Chevy Chase MCKINLEY ST Fort Circle Park Rec Center 27THST 4 3RD 3RD ST Francis G. Newlands Park (Little Forest) MILITARY RD Fort Slocum Park Riggs Fort M Emery B Circle LaSalle MISSOURIFort AVE L Park O Circle D Park A B NORTH CAPITOL ST R R R R OAD I E Fort Circle Park BR R A S N N R WESTERN AVE O C R G R H KENNEDY ST D G Fort O DR I D Linnean W R Bayard Park E Park R V NEBRASKA AVE D A ILLINOIS AVE FESSENDEN ST Keene O O Park Galen Tait RIVER RD LINNEAN AVE Rudolph Memorial Park D G Fort Circle Park 46THST Fort A F A Circle SOUTH DAKOTA AVE Hamilton O L A R Park L OW Y ST O GALLATIN Fort L R S Reno S T O T C G A Forest Rock Creek Park T Hills E O R Dalecarlia O G Parkway T Fort T R KANSAS AVE Totten E E Park E G N Westmoreland V N T T Circle I ALBEMARLE ST E CB A A SHERMAN CB D V JOHN MCCORMACK RD R Fort Circle ® S Sherman ® A A Park Tenley Circle A CIR NEW HAMPSHIRE AVE R D IOWA AVE V Y Circle N Soapstone S BUCHANAN ST E E H Valley W D N A K G W A A P A K II CB L AV A A ® B R WEBSTER ST E I D 49THST A L WISCONSIN AVE Upshur GRANT VAN NESS ST Grant R R Circle CIR H A Friendship CB UPSHUR ST C C ® CB 5TH ST R Petworth B E Twin Oaks ® U U TILDEN S Garden L T N H TAYLOR ST KER A C HIL Melvin L Hearst Rock Creek D C. -

Washington, Dc International Business Guide

WASHINGTON, DC INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS GUIDE Contents 1 Welcome Letter — Mayor Muriel Bowser 3 Introduction 5 Why Washington, DC? 6 A Powerful Economy Infographic 8 Awards and Recognition 9 Washington, DC — Demographics 11 Washington, DC — Economy 12 Federal Government 12 Retail and Federal Contractors Real Estate and Construction 13 12 Professional and Business Services 13 Higher Education and Healthcare 12 Technology and Innovation 13 Creative Economy 12 Hospitality and Tourism 15 Washington, DC — An Obvious Choice For International Companies 16 The District — Map 19 Washington, DC — Wards 25 Establishing A Business in Washington, DC 25 Business Registration 27 Office Space 27 Permits And Licenses 27 Business And Professional Services 27 Finding Talent 27 Small Business Services 27 Taxes 27 Employment-related Visas 29 Business Resources 31 Business Incentives and Assistance 32 DC Government by the Letter / Acknowledgements D C C H A M B E R O F C O M M E R C E Dear Investor, Washington, DC, is a thriving, global marketplace. Over the past decade, we have experienced significant growth and transformation. The District of Columbia has one of the most educated workforces in the country, stable economic growth, an established research community, and a business-friendly government. I am proud to present you with the Washington, DC International Business Guide. This book contains relevant information for foreign firms interested in establishing a presence in our nation’s capital. In these pages, you will find background on our strongest business sectors, economic indicators, and foreign direct investment trends. In addition, there are a number of suggested steps as you consider bringing your business to DC. -

June 2020 Newsletter

President's Message They say that this is the new normal and I can’t say that I like it but it seems like things have started to improve over the way that they were. People are able to get out and about a little easier and we are now starting to plan for upcoming golf tournaments! The course is in the best condition that it has ever been and kudos go out to our maintenance staff and Superintendent. The weekends are very busy and the new tee time format seems to be working out just fine, I have heard nothing but compliments from all of our members. I just want to remind everyone that we still have to follow the social distancing rules both on and off the course. Even though we are now in Phase 2 and will soon be in Phase 3, we can’t let our guard down or we could suffer setbacks in the spread of the virus. As always, if you want to reach me to discuss anything, please send me an email at roger.laime@aecom or call me on my cell phone at 518-772-7754. Please be considerate of others, be safe and think warm weather. Roger Laime Treasurer’s Report June 15th, 2020 I want all of our members to be aware, especially our newer members that you will see a bunker renovation fee on your July invoice. This is our final year of our 5 year bunker renovation project as Steve and his staff have recently completed #13. The fee will be 3% of dues for your membership category. -

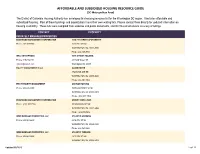

AFFORDABLE and SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area)

AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) The District of Columbia Housing Authority has developed this housing resource list for the Washington DC region. It includes affordable and subsidized housing. Most of these buildings and organizations have their own waiting lists. Please contact them directly for updated information on housing availability. These lists were compiled from websites and public documents, and DCHA cannot ensure accuracy of listings. CONTACT PROPERTY PRIVATELY MANAGED PROPERTIES EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION 1330 7TH STREET APARTMENTS Phone: 202-387-7558 1330 7TH ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3565 Phone: 202-387-7558 WEIL ENTERPRISES 54TH STREET HOUSING Phone: 919-734-1111 431 54th Street, SE [email protected] Washington, DC 20019 EQUITY MANAGEMENT II, LLC ALLEN HOUSE 3760 MINN AVE NE WASHINGTON, DC 20019-2600 Phone: 202-397-1862 FIRST PRIORITY MANAGEMENT ANCHOR HOUSING Phone: 202-635-5900 1609 LAWRENCE ST NE WASHINGTON, DC 20018-3802 Phone: (202) 635-5969 EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION ASBURY DWELLINGS Phone: (202) 745-7334 1616 MARION ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3468 Phone: (202)745-7434 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC GARDENS Phone: 202-561-8600 4216 4TH ST SE WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3325 Phone: 202-561-8600 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC TERRACE Phone: 202-561-8600 4319 19th ST S.E. WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3203 Updated 07/2013 1 of 17 AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) CONTACT PROPERTY Phone: 202-561-8600 HORNING BROTHERS AZEEZE BATES (Central -

ANC 7E Submission

Government of the District of Columbia ADVISORY NEIGHBORHOOD COMMISSION 7E Marshall Heights ▪ Benning Ridge ▪ Capitol View ▪ Fort Davis 3939 Benning Rd. NE 7E01 – Veda Rasheed Washington, D.C. 20019 7E02 – Linda S. Green, Vice-Chair [email protected] 7E03 – Ebbon Allen www.anc7e.us 7E04 – Takiyah “TN” Tate Twitter: @ANC7E 7E05 – Victor Horton, 7E06 – Delia Houseal, Chair 7E07 – Yolanda Fields, Secretary/Treasurer Executive Assistant, Jemila James RESOLUTION #: 7E-20-002 Recommendations on the DC Comprehensive Plan January 14, 2020 WHEREAS, Advisory Neighborhood Commissions (ANCs) were created to “advise the Council of the District of Columbia, the Mayor, and each executive agency with respect to all proposed matters of District government policy,” including education; WHEREAS, the government of the District of Columbia by law is required to give “great weight” to comments from ANCs; WHEREAS, the Bowser Administration is committed to ensuring the public’s voices and views are reflected in the update of the Comprehensive Plan; WHEREAS, Advisory Neighborhood Commission (ANC) 7E has conducted several public engagement activities to gather feedback from residents; THEREFORE BEFORE IT RESOLVED: The Advisory Neighborhood Commission (ANC) 7E puts forward the following recommendations: FAR SOUTHEAST/NORTHEAST ELEMENT Recommendations After careful review and consideration, ANC7E Recommends that language be added to the Far Northeast/Southeast Element to address the following issues: 1702. Land Use 1702.4. We recommend the following text updates: Commercial uses are clustered in nodes along Minnesota Avenue, East Capitol Street, Naylor Road, Pennsylvania Avenue, Nannie Helen Burroughs Avenue, Division Avenue, Central Avenue SE, H Street SE, and Benning Road (NE and SE). -

International Business Guide

WASHINGTON, DC INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS GUIDE Contents 1 Welcome Letter — Mayor Muriel Bowser 2 Welcome Letter — DC Chamber of Commerce President & CEO Vincent Orange 3 Introduction 5 Why Washington, DC? 6 A Powerful Economy Infographic8 Awards and Recognition 9 Washington, DC — Demographics 11 Washington, DC — Economy 12 Federal Government 12 Retail and Federal Contractors 13 Real Estate and Construction 12 Professional and Business Services 13 Higher Education and Healthcare 12 Technology and Innovation 13 Creative Economy 12 Hospitality and Tourism 15 Washington, DC — An Obvious Choice For International Companies 16 The District — Map 19 Washington, DC — Wards 25 Establishing A Business in Washington, DC 25 Business Registration 27 Office Space 27 Permits and Licenses 27 Business and Professional Services 27 Finding Talent 27 Small Business Services 27 Taxes 27 Employment-related Visas 29 Business Resources 31 Business Incentives and Assistance 32 DC Government by the Letter / Acknowledgements D C C H A M B E R O F C O M M E R C E Dear Investor: Washington, DC, is a thriving global marketplace. With one of the most educated workforces in the country, stable economic growth, established research institutions, and a business-friendly government, it is no surprise the District of Columbia has experienced significant growth and transformation over the past decade. I am excited to present you with the second edition of the Washington, DC International Business Guide. This book highlights specific business justifications for expanding into the nation’s capital and guides foreign companies on how to establish a presence in Washington, DC. In these pages, you will find background on our strongest business sectors, economic indicators, and foreign direct investment trends. -

District Columbia

PUBLIC EDUCATION FACILITIES MASTER PLAN for the Appendices B - I DISTRICT of COLUMBIA AYERS SAINT GROSS ARCHITECTS + PLANNERS | FIELDNG NAIR INTERNATIONAL TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX A: School Listing (See Master Plan) APPENDIX B: DCPS and Charter Schools Listing By Neighborhood Cluster ..................................... 1 APPENDIX C: Complete Enrollment, Capacity and Utilization Study ............................................... 7 APPENDIX D: Complete Population and Enrollment Forecast Study ............................................... 29 APPENDIX E: Demographic Analysis ................................................................................................ 51 APPENDIX F: Cluster Demographic Summary .................................................................................. 63 APPENDIX G: Complete Facility Condition, Quality and Efficacy Study ............................................ 157 APPENDIX H: DCPS Educational Facilities Effectiveness Instrument (EFEI) ...................................... 195 APPENDIX I: Neighborhood Attendance Participation .................................................................... 311 Cover Photograph: Capital City Public Charter School by Drew Angerer APPENDIX B: DCPS AND CHARTER SCHOOLS LISTING BY NEIGHBORHOOD CLUSTER Cluster Cluster Name DCPS Schools PCS Schools Number • Oyster-Adams Bilingual School (Adams) Kalorama Heights, Adams (Lower) 1 • Education Strengthens Families (Esf) PCS Morgan, Lanier Heights • H.D. Cooke Elementary School • Marie Reed Elementary School