“What Are Marines For?” the United States Marine Corps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John C. Calhoun and State Interposition in South Carolina, 1816-1833

Nullification, A Constitutional History, 1776-1833 Volume Three In Defense of the Republic: John C. Calhoun and State Interposition in South Carolina, 1816-1833 By Prof. W. Kirk Wood Alabama State University Contents Dedication Preface Acknowledgments Introduction In Defense of the Republic: John C. Calhoun and State Interposition in South Carolina, 1776-1833 Chap. One The Union of the States, 1800-1861 Chap. Two No Great Reaction: Republicanism, the South, and the New American System, 1816-1828 Chap. Three The Republic Preserved: Nullification in South Carolina, 1828-1833 Chap. Four Republicanism: The Central Theme of Southern History Chap. Five Myths of Old and Some New Ones Too: Anti-Nullifiers and Other Intentions Epilogue What Happened to Nullification and Republicanism: Myth-Making and Other Original Intentions, 1833- 1893 Appendix A. Nature’s God, Natural Rights, and the Compact of Government Revisited Appendix B. Quotes: Myth-Making and Original Intentions Appendix C. Nullification Historiography Appendix D. Abel Parker Upshur and the Constitution Appendix E. Joseph Story and the Constitution Appendix F. Dr. Wood, Book Reviews in the Montgomery Advertiser Appendix G. “The Permanence of the Union,” from William Rawle, A View of the Constitution of the United States (permission by the Constitution Society) Appendix H. Sovereignty, 1776-1861, Still Indivisible: States’ Rights Versus State Sovereignty Dedicated to the University and the people of South Carolina who may better understand and appreciate the history of the Palmetto State from the Revolution to the Civil War Preface Why was there a third Nullification in America (after the first one in Virginia in the 1790’s and a second one in New England from 1808 to 1815) and why did it originate in South Carolina? Answers to these questions, focusing as they have on slavery and race and Southern sectionalism alone, have made Southerners and South Carolinians feel uncomfortable with this aspect of their past. -

Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History

Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History Updated February 1, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45087 Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History Summary Censure is a reprimand adopted by one or both chambers of Congress against a Member of Congress, President, federal judge, or other government official. While Member censure is a disciplinary measure that is sanctioned by the Constitution (Article 1, Section 5), non-Member censure is not. Rather, it is a formal expression or “sense of” one or both houses of Congress. Censure resolutions targeting non-Members have utilized a range of statements to highlight conduct deemed by the resolutions’ sponsors to be inappropriate or unauthorized. Before the Nixon Administration, such resolutions included variations of the words or phrases unconstitutional, usurpation, reproof, and abuse of power. Beginning in 1972, the most clearly “censorious” resolutions have contained the word censure in the text. Resolutions attempting to censure the President are usually simple resolutions. These resolutions are not privileged for consideration in the House or Senate. They are, instead, considered under the regular parliamentary mechanisms used to process “sense of” legislation. Since 1800, Members of the House and Senate have introduced resolutions of censure against at least 12 sitting Presidents. Two additional Presidents received criticism via alternative means (a House committee report and an amendment to a resolution). The clearest instance of a successful presidential censure is Andrew Jackson. The Senate approved a resolution of censure in 1834. On three other occasions, critical resolutions were adopted, but their final language, as amended, obscured the original intention to censure the President. -

2014 National History Bee National Championships Round

2014 National History Bee National Championships Bee Finals BEE FINALS 1. Two men employed by this scientist, Jack Phillips and Harold Bride, were aboard the Titanic, though only the latter survived. A company named for this man was embroiled in an insider trading scandal involving Rufus Isaacs and Herbert Samuel, members of H.H. Asquith's cabinet. He shared the Nobel Prize with Karl Ferdinand Braun, and one of his first tests was aboard the SS Philadelphia, which managed a range of about two thousand miles for medium-wave transmissions. For the point, name this Italian inventor of the radio. ANSWER: Guglielmo Marconi 048-13-94-25101 2. A person with this surname died while piloting a plane and performing a loop over his office. Another person with this last name was embroiled in an arms-dealing scandal with the business Ottavio Quattrochi and was killed by a woman with an RDX-laden belt. This last name is held by "Sonia," an Italian-born Catholic who declined to become prime minister in 2004. A person with this last name declared "The Emergency" and split the Congress Party into two factions. For the point, name this last name shared by Sanjay, Rajiv, and Indira, the latter of whom served as prime ministers of India. ANSWER: Gandhi 048-13-94-25102 3. This man depicted an artist painting a dog's portrait with his family in satire of a dog tax. Following his father's commitment to Charenton asylum, this painter was forced to serve as a messenger boy for bailiffs, an experience which influenced his portrayals of courtroom scenes. -

The Rewards of Risk-Taking: Two Civil War Admirals*

The 2014 George C. Marshall Lecture in Military History The Rewards of Risk-Taking: Two Civil War Admirals* James M. McPherson Abstract The willingness to take risks made Rear Admiral David Glasgow Far- ragut, victor at New Orleans in 1862 and Mobile Bay in 1864, the Union’s leading naval commander in the Civil War. Farragut’s boldness contrasted strongly with the lack of decisiveness shown in the failure in April 1863 to seize the port of Charleston, South Carolina, by Rear Admiral Samuel Francis Du Pont, whose capture of Port Royal Sound in South Carolina in November of 1861 had made him the North’s first naval hero of the war. Du Pont’s indecisiveness at Charleston led to his removal from command and a blighted career, while the risk-taking Farragut went on to become, along with generals U.S. Grant and Wil- liam T. Sherman, one of the principal architects of Union victory. n September 1864 Captain Charles Steedman of the United States Navy praised Rear Admiral David Glasgow Farragut for his decisive victory over ConfederateI forts and warships in the Battle of Mobile Bay the previous month. “That little man,” wrote Steedman of the wiry Farragut who was actually just * This essay derives from the George C. Marshall Lecture on Military History, delivered on 4 January 2014 at the annual meeting of the American Historical Association, Washington, D.C. The Marshall Lecture is sponsored by the Society for Military History and the George C. Marshall Foundation. James M. McPherson earned a Ph.D. at Johns Hopkins University in 1963 and from 1962 to 2004 taught at Princeton University, where he is currently the George Henry Davis ’86 Profes- sor of American History Emeritus. -

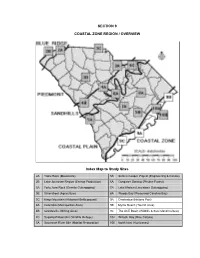

Coastal Zone Region / Overview

SECTION 9 COASTAL ZONE REGION / OVERVIEW Index Map to Study Sites 2A Table Rock (Mountains) 5B Santee Cooper Project (Engineering & Canals) 2B Lake Jocassee Region (Energy Production) 6A Congaree Swamp (Pristine Forest) 3A Forty Acre Rock (Granite Outcropping) 7A Lake Marion (Limestone Outcropping) 3B Silverstreet (Agriculture) 8A Woods Bay (Preserved Carolina Bay) 3C Kings Mountain (Historical Battleground) 9A Charleston (Historic Port) 4A Columbia (Metropolitan Area) 9B Myrtle Beach (Tourist Area) 4B Graniteville (Mining Area) 9C The ACE Basin (Wildlife & Sea Island Culture) 4C Sugarloaf Mountain (Wildlife Refuge) 10A Winyah Bay (Rice Culture) 5A Savannah River Site (Habitat Restoration) 10B North Inlet (Hurricanes) TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR SECTION 9 COASTAL ZONE REGION / OVERVIEW - Index Map to Coastal Zone Overview Study Sites - Table of Contents for Section 9 - Power Thinking Activity - "Turtle Trot" - Performance Objectives - Background Information - Description of Landforms, Drainage Patterns, and Geologic Processes p. 9-2 . - Characteristic Landforms of the Coastal Zone p. 9-2 . - Geographic Features of Special Interest p. 9-3 . - Carolina Grand Strand p. 9-3 . - Santee Delta p. 9-4 . - Sea Islands - Influence of Topography on Historical Events and Cultural Trends p. 9-5 . - Coastal Zone Attracts Settlers p. 9-5 . - Native American Coastal Cultures p. 9-5 . - Early Spanish Settlements p. 9-5 . - Establishment of Santa Elena p. 9-6 . - Charles Towne: First British Settlement p. 9-6 . - Eliza Lucas Pinckney Introduces Indigo p. 9-7 . - figure 9-1 - "Map of Colonial Agriculture" p. 9-8 . - Pirates: A Coastal Zone Legacy p. 9-9 . - Charleston Under Siege During the Civil War p. 9-9 . - The Battle of Port Royal Sound p. -

By the History Workshop Table of Contents

THINK LIKE A HISTORIAN BY THE HISTORY WORKSHOP TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: ............................................................................................................................................3 SUGGESTED GRADE LEVEL: .........................................................................................................................3 OBJECTIVES: .................................................................................................................................................3 MATERIALS: ..................................................................................................................................................3 BACKGROUND INFORMATION: ......................................................................................................................4 UNDERSTANDING MITCHELVILLE ...................................................................................................4 DOING HISTORICAL RESEARCH: .....................................................................................................15 LESSON ACTIVITIES: .....................................................................................................................................17 TEACHER GUIDANCE QUESTIONS: ..................................................................................................19 STANDARDS: ...................................................................................................................................19 RESOURCES: ....................................................................................................................................20 -

Naval Affairs

.t .j f~Ji The New I American State Papers I ~ '* NAVAL AFFAIRS Volume 2 Diplomatic Activities Edited lJy K. Jack Bauer ~c:!:r~ourres Inc. I q8/ Leadership ofthe Navy Department 1798-1~61 Sea:etaries o/the NfZJJYl Benjamin Stoddert2 18 June 1798-31 March 1801 Robert Smith 27 July 1801-7 March 1809 Paul Hamilton 15 May 1809-31 December 1812 William Jones 19 January 1813-1 December 1814 Benjamin W. Crowninshield 16 January 1815-30 September 1818 Smith Thompson 1January 1819-31 August 1823 Samuel L. Southard 16 Septe~ber 1823-3 March 1829 John Branch 9 March 1829-.12 May 1831 Levi Woodbury 23 May 1831-30June 1834 Mahlon Dickerson 1July 1834-30June 1838 James K. Paulding 1July 1838-3 March 1841 George E. Badger 6 March 1841-11 September 1841 Abel P. Upshur 11 October 1841-23July 1843 David Henshaw 24 July 1843-18 February 1844 Thomas W. Gilmer 19 February 1844-28 February 1844 John Y. Mason 26 March 1844-10 March 1845 George Bancroft 11 March 1845-9 September 1846 John Y. Mason 10 September 1846-7. March 1849 William B. Preston 8 March 1849-23July 1850 William A. Graham 2 August 1850-25July 1852 John P. Kennedy 26 July 1852-7 March 1853 James C. 'Dobbin 8 March 1853-6 March 1857 Isaac Toucey 7 March 1857-6 March 1861 Board o/Naval Commissioners, 7 February 181'-)1 August 1842 Comm. John Rodgers3 25 April 1815-15 December 1824 Comm. Isaac Hull 25 April 1815-.30 November 1815 I Prior to 1798 naval affairs were administered by the War Department. -

GUNS Magazine January 1959

JANUARY 1959 SOc fIIEST III THE fllUUlS finD HUNTING- SHOOTING -ADVENTURE 1958 NATIONAL DOUBLES CHAMPION JOE HIESTAND • Ohio State Champion-9 times • Amateur Clay Target Champion of America-4 times • Doubles Champion of America 3 times • High Over All Champion-7 times • Hiestand has the remarka'ble record of having broken 200 out of 200 fifty times. • Hiestand has the world's record of having broken 1,404 registered targets straight without missing a one. Champions like Joe Hiestand de pend on the constant performance of CCI primers. The aim of CCI Champions like Joe Hiestand de pend on the constant performance of CCI primers. The aim of cel is to continue to produce the finest quality primers for Ameri can shooters. .' Rely on CCI PRIMERS American Made ~ Large and Small Rifle, 8.75 per M Large and Small Pistol, 8.75 per M Shotshell Caps, 8.75 per M Shotshell, 15.75 per M ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ~~~~~ ~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ~ TWO IDEAL CHRISTMAS GIFTS ... ~ ·tgfJi'Yo, ~ , ~ ~ ; ,.;- '.. •22,iSPRINCiFIELD CONVERSION UNIT .fSmash;n,g Fits Any M 1903 Springfield " j poWer BARREL INSERT MAGAZINE PERFECT FOR TRAININ~ I YOUNGSTERS AT LOW COST 12 SPRINGFIELD BOLT Only $34.50 ppd. (Extra magazine-$1.75) ~~f:~~"~? .~O.~Et~e t';p.er. The ~ ••nd ee..4 --.--- ~ ,~ :.'t =.r ' ~~~in~~ ;n(l ~:::~ u: i ~~ i~: »)l~~~:~~~s .•-:: isst:lnd~usrr;-e:~ . Id eal for practice using" .22 l.r, ammo. Think of the ]noney you Save . W hy pu c away your .22 Target p i at ol l ines, ru g . ge~ mct a~ alloy Ir- blue- Sp ringfie ld spor rer wh en high pow er season is ove r, quick ly conve rt it in to a super accurate ~~i~~ c:: ~n~~p er5~:: :~1n ef~ ~pa:i;~d Ol~ 5~~~ l~O~:~ot:i "Man-sized" .22 re peater. -

Harriet Lane Steve Schulze Camp Commander

SONS OF UNION VETERANS OF THE CIVIL WAR Lt. Commander Edward Lea U.S.N. – Camp Number 2 Harriet Lane *************************************************************************************** Summer 2007 Volume 14 Number 2 ************************************************************************************** From the Commander’s Tent Here we go again. Its summer with all the bustle and activity associated with the season. School is out, everyone’s looking forward to their vacations and the pace of life in some ways is even more frantic than during the other seasons of the year. The Camp just completed one of its most important evolutions - Memorial Day. We had nine Brothers at the National Cemetery, with eight in period uniform. I think this is the best uniformed turnout we’ve ever had, at least in my memory. We are also in the process of forming a unit of the Sons of Veteran’s Reserve. We have ten prospective members from our Camp. Brother Dave LaBrot is the prospective commanding officer. All we are waiting for is for the James J. Byrne Camp #1 to send down their seven applications so the paperwork can be turned in. We should then soon have the unit up and running. I hope that even more Brothers will join as we get rolling. I have been watching with great interest the way the level of awareness of and the desire to learn about the Civil War in particular, and the 1860’s in general, has been growing throughout the nation during the last few years. In part this may be because we are coming up upon another milestone period (the 150th anniversary). But also I think more people are realizing the importance of the events of that era and the extent that we are still being affected by them today. -

All Saints Church, Waccamaw Photo Hy Ski1,11Er

All Saints Church, Waccamaw Photo hy Ski1,11er ALL SAINTS' CHURCH, WACCAMAW THE PARISH: THE· PLACE: THE PEOPLE. ---•-•.o• ◄ 1739-1948 by HENRY DeSAUSSURE BULL Published by The Historical Act-ivities Committee of the South Carolina Sociefy o'f' Colonial Dames of America 1948 fl'IIINTED 8Y JOHN J. FURLONG a SONS CHARLESTON, 5, C, This volume is dedicated to the memo,-y of SARAH CONOVER HOLMES VON KOLNITZ in grateful appr.eciation of her keen interest in the history of our State. Mrs. Von Kolnit& held the following offices in the South Carolina Society of Colonial Dames of America : President 193S-1939 Honorary President 1939-1943 Chairman of Historic Activities Committte 1928-1935 In 1933 she had the honor of being appointed Chairman of Historic Activities Committee of the National Society of Colonial Dames of America ·which office she held with con spicuous ability until her death on April 6th 1943. CHURCH, W ACCAMA ALL SAINTS' • 'Ai 5 CHAPTER I - BEGINNING AND GROWTH All Saint's Parish includes the whole of vVaccamaw peninsula, that narrow tongue of land lying along the coast of South Caro~ lina, bounded on the east by the Atlantic and on the \Vest by the Waccamaw River which here flo\vs almost due south and empties into Winyah Bay. The length of the "N eek" from Fraser's Point to the Horry County line just north of Murrell's Inlet is about thirty miles and the width of the high land varies f rorii two to three miles. The :place takes its name from the \Vac~ camaws, a small Indian tribe of the locality who belonged ·to a loose conf ederacv.. -

Medallic History of the War of 1812: Catalyst for Destruction of the American Indian Nations by Benjamin Weiss Published By

Medallic History of the War of 1812: Catalyst for Destruction of the American Indian Nations by Benjamin Weiss Published by Kunstpedia Foundation Haansberg 19 4874NJ Etten-Leur the Netherlands t. +31-(0)76-50 32 797 f. +31-(0)76-50 32 540 w. www.kunstpedia.org Text : Benjamin Weiss Design : Kunstpedia Foundation & Rifai Publication : 2013 Copyright Benjamin Weiss. Medallic History of the War of 1812: Catalyst for Destruction of the American Indian Nations by Benjamin Weiss is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://www.kunstpedia.org. “Brothers, we all belong to one family; we are all children of the Great Spirit; we walk in the same path; slake our thirst at the same spring; and now affairs of the greatest concern lead us to smoke the pipe around the same council fire!” Tecumseh, in a speech to the Osages in 1811, urging the Indian nations to unite and to forewarn them of the calamities that were to come (As told by John Dunn Hunter). Historical and commemorative medals can often be used to help illustrate the plight of a People. Such is the case with medals issued during the period of the War of 1812. As wars go, this war was fairly short and had relatively few casualties1, but it had enormous impact on the future of the countries and inhabitants of the Northern Hemisphere. At the conclusion of this conflict, the geography, destiny and social structure of the newly-formed United States of America and Canada were forever and irrevocably altered. -

University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating' adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation.