Volume 27 , Number 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Position Was Finely Adapted to Its Use...”

"...Our Position Was Finely Adapted To Its Use...” The Guns of Cemetery Hill Bert H. Barnett During the late afternoon of July 1, 1863, retiring Federals of the battered 1st and 11th corps withdrew south through Gettysburg toward Cemetery Hill and began to steady themselves upon it. Following the difficult experiences of the first day of battle, many officers and men were looking to that solid piece of ground, seeking all available advantages. A number of factors made this location attractive. Chief among them was a broad, fairly flat crest that rose approximately eighty feet above the center of Gettysburg, which lay roughly three-quarters of a mile to the north. Cemetery Hill commanded the approaches to the town from the south, and the town in turn served as a defensive bulwark against organized attack from that quarter. To the west and southwest of the hill, gradually descending open slopes were capable of being swept by artillery fire. The easterly side of the hill was slightly lower in height than the primary crest. Extending north of the Baltimore pike, it possessed a steeper slope that overlooked low ground, cleared fields, and a small stream. Field guns placed on this position would also permit an effective defense. It was clear that this new position possessed outstanding features. General Oliver Otis Howard, commanding the Union 11th Corps, pronounced it “the only tenable position” for the army.1 As the shadows began to lengthen on July 1, it became apparent that Federal occupation of the hill was not going to be challenged in any significant manner this day. -

Väsen I Chronopia Creatures of Chronopia Konstruktör: Johan

Väsen i Chronopia Creatures of Chronopia Konstruktör: Johan Sjöberg Översättning: Redigering: Chronopia: Bill King, Michael Stenmark, Nils Gulliksson, Henrik Strandberg Formgivning: Original: Marcus Thorell Omslag: Adrian Smith Grafisk Form: Illustrationer: Adrian Smith, Alvaro Tapia Koncept: Stefan Ljungqvist, Johan Sjöberg Kartor: Övriga Bidrag: Filip Alexanderson, Hanners Kristoferson, Fredrik Malmberg, Henrik Strandberg, Nils Gulliksson, Sami Sinerva, Jonas Mases, Patric Backlund, Cees Kwadijk Baksida: Paolo Parente Projektledning: Stefan Ljungqvist So you want to learn something about the chronopian people? Forsa the sabranska mysteries, get to know the secrets that made brundusierna so rich, understand marajiputternas brutal fanaticism and unconditional surrender to the black tobacco, nattländarnas desperate escape and ice barbarians worship of Snow Witch. Then I have the book for you my friend. Just look up Melkastors "The chronopian peoples", which delivers the wise man and adventurer all the wisdom you need. If he is still alive? No. When the book arrived, he was executed for blasphemy by the emperor. Read - and maybe you will understand why. Human ethnicities During my many long and intense years as a guest in the brutal, multifaceted and legendary chronopian reality, I had the dubious pleasure to encounter the most varied gallery of the known world has to offer, bump into high and low, exchange experiences with sabranska desert knights, brundusiska trade princes and blue skinned isbarbarer with frosty mustache. I have engaged in telepathy with charibiska hexbarons, given boozed Red Corsairs on the nut, fled howling marajiputtiska fanatics and young and inexperienced taken refuge in faltrakiernas false bosom and sold as a slave to the salt mines. -

The Negro Press and the Image of Success: 1920-19391 Ronald G

the negro press and the image of success: 1920-19391 ronald g. waiters For all the talk of a "New Negro," that period between the first two world wars of this century produced many different Negroes, just some of them "new." Neither in life nor in art was there a single figure in whose image the whole race stood or fell; only in the minds of most Whites could all Blacks be lumped together. Chasms separated W. E. B. DuBois, icy, intellectual and increasingly radical, from Jesse Binga, prosperous banker, philanthropist and Roman Catholic. Both of these had little enough in common with the sharecropper, illiterate and bur dened with debt, perhaps dreaming of a North where—rumor had it—a man could make a better living and gain a margin of respect. There was Marcus Garvey, costumes and oratory fantastic, wooing the Black masses with visions of Africa and race glory while Father Divine promised them a bi-racial heaven presided over by a Black god. Yet no history of the time should leave out that apostle of occupational training and booster of business, Robert Russa Moton. And perhaps a place should be made for William S. Braithwaite, an aesthete so anonymously genteel that few of his White readers realized he was Black. These were men very different from Langston Hughes and the other Harlem poets who were finding music in their heritage while rejecting capitalistic America (whose chil dren and refugees they were). And, in this confusion of voices, who was there to speak for the broken and degraded like the pitiful old man, born in slavery ninety-two years before, paraded by a Mississippi chap ter of the American Legion in front of the national convention of 1923 with a sign identifying him as the "Champeen Chicken Thief of the Con federate Army"?2 In this cacaphony, and through these decades of alternate boom and bust, one particular voice retained a consistent message, though condi tions might prove the message itself to be inconsistent. -

Catherine Mary White Foster's Eyewitness Account of the Battle of Gettysburg, with Background on the Foster Family Union Soldiers David A

Volume 1 Article 5 1995 Catherine Mary White Foster's Eyewitness Account of the Battle of Gettysburg, with Background on the Foster Family Union Soldiers David A. Murdoch Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ach Part of the Military History Commons, United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Murdoch, David A. (1995) "Catherine Mary White Foster's Eyewitness Account of the Battle of Gettysburg, with Background on the Foster Family Union Soldiers," Adams County History: Vol. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ach/vol1/iss1/5 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Catherine Mary White Foster's Eyewitness Account of the Battle of Gettysburg, with Background on the Foster Family Union Soldiers Abstract Catherine Mary White Foster lived with her elderly parents in the red brick house on the northwest corner of Washington and High Streets in Gettysburg at the time of the battle, 1-3 July 1863. She was the only child of James White Foster and Catherine (nee Swope) Foster (a former resident of Lancaster county), who married on 11 May 1817 and settled in Gettysburg, Adams county, Pennsylvania. Her father, James White Foster, had served his country as a first lieutenant in the War of 1812. Her grandparents, James Foster and Catherine (nee White) Foster, had emigrated with her father and five older children from county Donegal, Ireland, in 1790, and settled near New Alexandria, Westmoreland county, Pennsylvania. -

News Deserts and Ghost Newspapers: Will Local News Survive?

NEWS DESERTS AND GHOST NEWSPAPERS: WILL LOCAL NEWS SURVIVE? PENELOPE MUSE ABERNATHY Knight Chair in Journalism and Digital Media Economics Will Local News Survive? | 1 NEWS DESERTS AND GHOST NEWSPAPERS: WILL LOCAL NEWS SURVIVE? By Penelope Muse Abernathy Knight Chair in Journalism and Digital Media Economics The Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media School of Media and Journalism University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2 | Will Local News Survive? Published by the Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media with funding from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Office of the Provost. Distributed by the University of North Carolina Press 11 South Boundary Street Chapel Hill, NC 27514-3808 uncpress.org Will Local News Survive? | 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 5 The News Landscape in 2020: Transformed and Diminished 7 Vanishing Newspapers 11 Vanishing Readers and Journalists 21 The New Media Giants 31 Entrepreneurial Stalwarts and Start-Ups 40 The News Landscape of the Future: Transformed...and Renewed? 55 Journalistic Mission: The Challenges and Opportunities for Ethnic Media 58 Emblems of Change in a Southern City 63 Business Model: A Bigger Role for Public Broadcasting 67 Technological Capabilities: The Algorithm as Editor 72 Policies and Regulations: The State of Play 77 The Path Forward: Reinventing Local News 90 Rate Your Local News 93 Citations 95 Methodology 114 Additional Resources 120 Contributors 121 4 | Will Local News Survive? PREFACE he paradox of the coronavirus pandemic and the ensuing economic shutdown is that it has exposed the deep Tfissures that have stealthily undermined the health of local journalism in recent years, while also reminding us of how important timely and credible local news and information are to our health and that of our community. -

Andrew Johnson, the Freedmen's Bureau, and the Problem of Equal Rights, 1865-1866 Author(S): Donald G

Southern Historical Association Andrew Johnson, the Freedmen's Bureau, and the Problem of Equal Rights, 1865-1866 Author(s): Donald G. Nieman Reviewed work(s): Source: The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 44, No. 3 (Aug., 1978), pp. 399-420 Published by: Southern Historical Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2208049 . Accessed: 01/11/2012 12:11 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Southern Historical Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Southern History. http://www.jstor.org Andrew Johnson, the Freedmen's Bureau, and the Problem of Equal Rights, 1865-1866 By DONALD G. NIEMAN DURING THE SUMMER AND FALL OF 1865, AS THE NEWLY CREATED Freedmen's Bureau commenced its operations, one of the chief concerns of its officials was providing freedmen with legal pro- tection. Antebellum southern state law had discriminated harshly against free blacks, and in the Civil War's aftermath functionaries of the provisional governments created in the rebel states by Presi- dents Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson stood ready to apply this law to the freedmen. State officials' willingness to enforce discriminatory law, however, was not the only reason they posed a threat to blacks. -

Some Pages from the Book

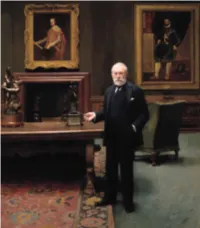

AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 2 16/3/21 18:49 What’s Mine Is Yours Private Collectors and Public Patronage in the United States Essays in Honor of Inge Reist edited by Esmée Quodbach AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 3 16/3/21 18:49 first published by This publication was organized by the Center for the History of Collecting at The Frick Collection and Center for the History of Collecting Frick Art Reference Library, New York, the Centro Frick Art Reference Library, The Frick Collection de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH), Madrid, and 1 East 70th Street the Center for Spain in America (CSA), New York. New York, NY 10021 José Luis Colomer, Director, CEEH and CSA Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica Samantha Deutch, Assistant Director, Center for Felipe IV, 12 the History of Collecting 28014 Madrid Esmée Quodbach, Editor of the Volume Margaret Laster, Manuscript Editor Center for Spain in America Isabel Morán García, Production Editor and Coordinator New York Laura Díaz Tajadura, Color Proofing Supervisor John Morris, Copyeditor © 2021 The Frick Collection, Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, and Center for Spain in America PeiPe. Diseño y Gestión, Design and Typesetting Major support for this publication was provided by Lucam, Prepress the Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH) Brizzolis, Printing and the Center for Spain in America (CSA). Library of Congress Control Number: 2021903885 ISBN: 978-84-15245-99-5 Front cover image: Charles Willson Peale DL: M-5680-2021 (1741–1827), The Artist in His Museum. 1822. Oil on canvas, 263.5 × 202.9 cm. -

AMERICAN MANHOOD in the CIVIL WAR ERA a Dissertation Submitted

UNMADE: AMERICAN MANHOOD IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Michael E. DeGruccio _________________________________ Gail Bederman, Director Graduate Program in History Notre Dame, Indiana July 2007 UNMADE: AMERICAN MANHOOD IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA Abstract by Michael E. DeGruccio This dissertation is ultimately a story about men trying to tell stories about themselves. The central character driving the narrative is a relatively obscure officer, George W. Cole, who gained modest fame in central New York for leading a regiment of black soldiers under the controversial General Benjamin Butler, and, later, for killing his attorney after returning home from the war. By weaving Cole into overlapping micro-narratives about violence between white officers and black troops, hidden war injuries, the personal struggles of fellow officers, the unbounded ambition of his highest commander, Benjamin Butler, and the melancholy life of his wife Mary Barto Cole, this dissertation fleshes out the essence of the emergent myth of self-made manhood and its relationship to the war era. It also provides connective tissue between the top-down war histories of generals and epic battles and the many social histories about the “common soldier” that have been written consciously to push the historiography away from military brass and Lincoln’s administration. Throughout this dissertation, mediating figures like Cole and those who surrounded him—all of lesser ranks like major, colonel, sergeant, or captain—hem together what has previously seemed like the disconnected experiences of the Union military leaders, and lowly privates in the field, especially African American troops. -

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Ralph

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Ralph H. Records Collection Records, Ralph Hayden. Papers, 1871–1968. 2 feet. Professor. Magazine and journal articles (1946–1968) regarding historiography, along with a typewritten manuscript (1871–1899) by L. S. Records, entitled “The Recollections of a Cowboy of the Seventies and Eighties,” regarding the lives of cowboys and ranchers in frontier-era Kansas and in the Cherokee Strip of Oklahoma Territory, including a detailed account of Records’s participation in the land run of 1893. ___________________ Box 1 Folder 1: Beyond The American Revolutionary War, articles and excerpts from the following: Wilbur C. Abbott, Charles Francis Adams, Randolph Greenfields Adams, Charles M. Andrews, T. Jefferson Coolidge, Jr., Thomas Anburey, Clarence Walroth Alvord, C.E. Ayres, Robert E. Brown, Fred C. Bruhns, Charles A. Beard and Mary R. Beard, Benjamin Franklin, Carl Lotus Belcher, Henry Belcher, Adolph B. Benson, S.L. Blake, Charles Knowles Bolton, Catherine Drinker Bowen, Julian P. Boyd, Carl and Jessica Bridenbaugh, Sanborn C. Brown, William Hand Browne, Jane Bryce, Edmund C. Burnett, Alice M. Baldwin, Viola F. Barnes, Jacques Barzun, Carl Lotus Becker, Ruth Benedict, Charles Borgeaud, Crane Brinton, Roger Butterfield, Edwin L. Bynner, Carl Bridenbaugh Folder 2: Douglas Campbell, A.F. Pollard, G.G. Coulton, Clarence Edwin Carter, Harry J. Armen and Rexford G. Tugwell, Edward S. Corwin, R. Coupland, Earl of Cromer, Harr Alonzo Cushing, Marquis De Shastelluz, Zechariah Chafee, Jr. Mellen Chamberlain, Dora Mae Clark, Felix S. Cohen, Verner W. Crane, Thomas Carlyle, Thomas Cromwell, Arthur yon Cross, Nellis M. Crouso, Russell Davenport Wallace Evan Daview, Katherine B. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2014 Remarks on Presenting

Administration of Barack Obama, 2014 Remarks on Presenting Posthumously the Medal of Honor to First Lieutenant Alonzo H. Cushing November 6, 2014 Please, everyone, have a seat. Well, on behalf of Michelle and myself, welcome to the White House. One hundred fifty-one years ago, as our country struggled for its survival, President Lincoln dedicated the battlefield at Gettysburg as "a final resting place for those who died here, that the nation might live." Today the nation that lived pauses to pay tribute to one of those who died there: to bestow the Medal of Honor, our highest military decoration, upon First Lieutenant Alonzo H. Cushing. Now, typically, this medal must be awarded within a few years of the action. But sometimes, even the most extraordinary stories can get lost in the passage of time. So I want to thank the more than two dozen family members of Lieutenant Cushing who are here, including his cousin, twice removed, Helen Loring Ensign, from Palm Desert, California, who will accept this medal. For this American family, this story isn't some piece of obscure history, it is an integral part of who they are. And today our whole Nation shares their pride and celebrates what this story says about who we are. This award would not have been possible without the tireless efforts of supporters who worked for decades to make this day a reality. And I want to especially acknowledge Margaret Zerwekh, who is a historian from Delafield, Wisconsin, where Lieutenant Cushing was born. And there's Margaret back there. [Laughter] Good to see you, Margaret. -

William Penn's Chair and George

WILLIAM PENN’S CHAIR AND GEORGE WASHINGTON’S HAIR: THE POLITICAL AND COMMERCIAL MEANINGS OF OBJECTS AT THE PHILADELPHIA GREAT CENTRAL FAIR, 1864 by Justina Catherine Barrett A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Early American Culture Spring 2005 Copyright 2005 Justina Catherine Barrett All rights reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1426010 Copyright 2005 by Barrett, Justina Catherine All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 1426010 Copyright 2005 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. WILLIAM PENN’S CHAIR AND GEORGE WASHINGTON’S HAIR: THE POLITICAL AND COMMERCIAL MEANINGS OF OBJECTS AT THE PHILADELPHIA GREAT CENTRAL FAIR, 1864 By Justina Catherine Barrett Approved: _______ Pauline K. Eversmann, M. Phil. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: J. -

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: from Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare By

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: From Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare by Matthew A. Bellamy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2018 Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Najita, Chair Professor Daniel Hack Professor Mika Lavaque-Manty Associate Professor Andrea Zemgulys Matthew A. Bellamy [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-6914-8116 © Matthew A. Bellamy 2018 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to all my students, from those in Jacksonville, Florida to those in Port-au-Prince, Haiti and Ann Arbor, Michigan. It is also dedicated to the friends and mentors who have been with me over the seven years of my graduate career. Especially to Charity and Charisse. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication ii List of Figures v Abstract vi Chapter 1 Introduction: Espionage as the Loss of Agency 1 Methodology; or, Why Study Spy Fiction? 3 A Brief Overview of the Entwined Histories of Espionage as a Practice and Espionage as a Cultural Product 20 Chapter Outline: Chapters 2 and 3 31 Chapter Outline: Chapters 4, 5 and 6 40 Chapter 2 The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 1: Conspiracy, Bureaucracy and the Espionage Mindset 52 The SPECTRE of the Many-Headed HYDRA: Conspiracy and the Public’s Experience of Spy Agencies 64 Writing in the Machine: Bureaucracy and Espionage 86 Chapter 3: The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 2: Cruelty and Technophilia