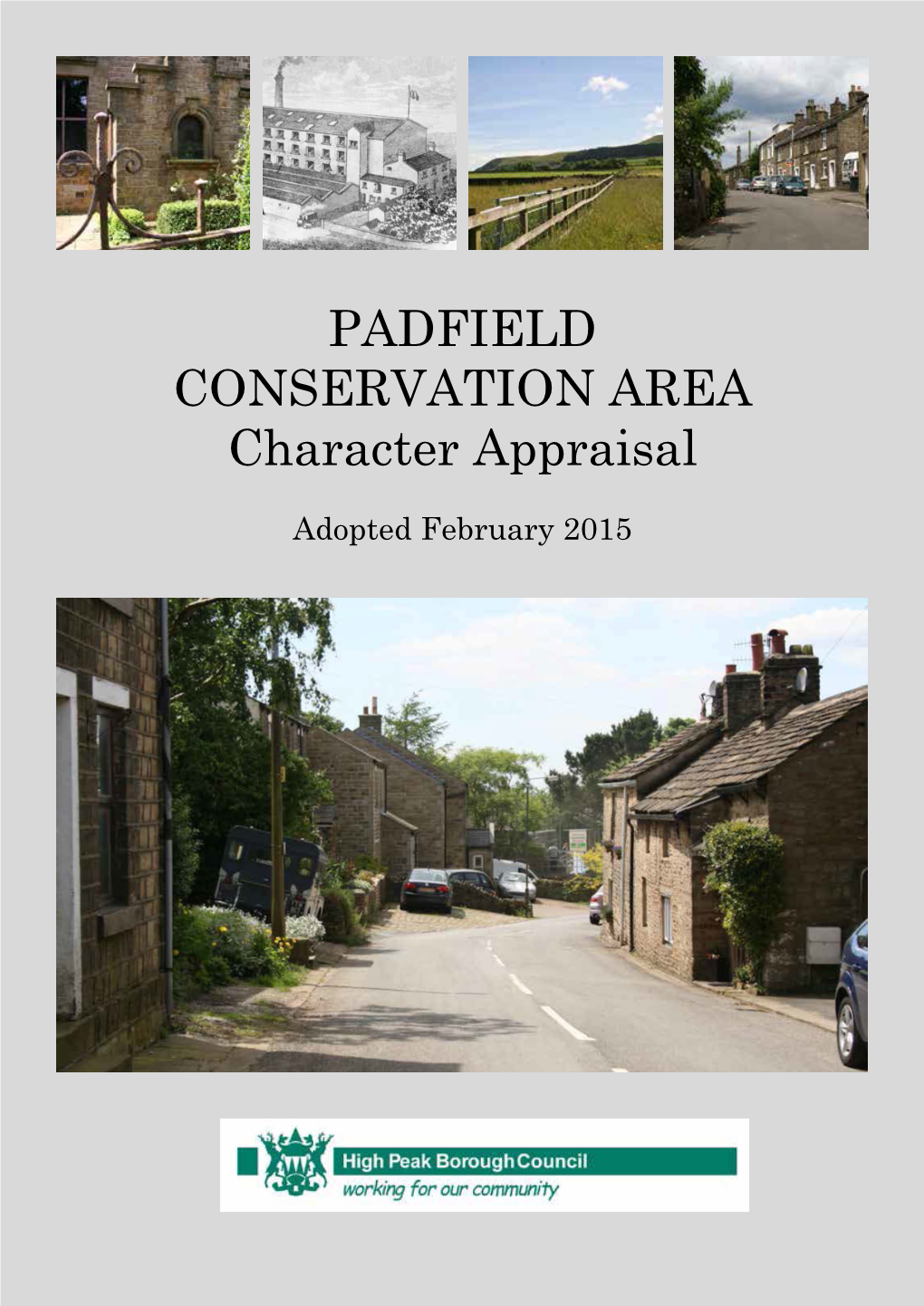

PADFIELD CONSERVATION AREA Character Appraisal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peak Sub Region

Peak Sub Region Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment Final Report to Derbyshire Dales District Council, High Peak Borough Council and the Peak District National Park Authority June 2009 ekosgen Lawrence Buildings 2 Mount Street Manchester M2 5WQ TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................ 5 STUDY INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................. 5 OVERVIEW OF THE STUDY AREA ............................................................................................... 5 ROLE OF THE STUDY ................................................................................................................ 8 REPORT STRUCTURE.............................................................................................................. 10 2 SHLAA GUIDANCE AND STUDY METHODOLOGY..................................................... 12 SHLAA GUIDANCE................................................................................................................. 12 STUDY METHODOLOGY........................................................................................................... 13 3 POLICY CONTEXT.......................................................................................................... 18 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 18 NATIONAL, REGIONAL AND -

HP Councillors Initiative Fund 2018

High Peak Borough Council Councillor's Initiative Fund 2018-2019 Projects Project Group Name Project Name Total Agreed £ Councillor(s) Ward Ref CIF CIF 2 Glossop Arts Project “Arts for Wellbeing” 650.00 100.00 Longos, Nick Padfield 100.00 Hardy, Paul Old Glossop 200.00 Kelly, Ed Hadfield North 250.00 Claff, Godfrey Howard Town CIF 3 Glossop Arts Project “Arts for Wellbeing” 200.00 Wharmby, Jean Dinting CIF 4 Dove Holes Cricket Club Upgrading of security 250.00 Roberts, Peter Limestone Peak lighting CIF 5 Gloss Group Social Activities Project 200.00 Wharmby, Jean Dinting CIF 6 Tintwistle Ladies Well Dressing 200.00 Jenner, Pat Tintwistle CIF 7 GYGs - Gamesley Youth GYGs 80.00 McKeown, Anthony Gamesley Gatherings CIF 8 People of Whitfield Whitfield Food Club 200.00 Oakley, Graham Whitfield CIF 9 Buxton Town Team Fairfield Road – Gateway 350.00 Quinn, Rachael Barms to Buxton CIF 10 Eat Well Glossop CIC Eat Well Whitfield 400.00 200.00 Oakley, Graham Whitfield 100.00 Claff, Godfrey Howard Town 100.00 Greenhalgh, Damien Howard Town CIF 11 Wellbeing Group Social Activities 250.00 Fox, Andrew Whaley Bridge CIF 12 Glossop Arts Project “Arts for Wellbeing” 100.00 Greenhalgh, Damien Howard Town CIF 13 Harpur Hill Residents Harpur Hill Community 150.00 Grooby, Linda Cote Heath Association Fun Day CIF 14 Glossopdale Foodbank Glossopdale Foodbank 125.00 Claff, Godfrey Howard Town CIF 15 Glossopdale Foodbank Glossopdale Foodbank 320.00 80.00 Greenhalgh, Damien Howard Town 80.00 Oakley, Graham Whitfield 80.00 Hardy, Paul Old Glossop 80.00 Kelly, Ed Hadfield -

New Mills Library: Local History Material (Non-Book) for Reference

NEW MILLS LIBRARY: LOCAL HISTORY MATERIAL (NON-BOOK) FOR REFERENCE. Microfilm All the microfilm is held in New Mills Library, where readers are available. It is advisable to book a reader in advance to ensure one is available. • Newspapers • "Glossop Record", 1859-1871 • "Ashton Reporter"/"High Peak Reporter", 1887-1996 • “Buxton Advertiser", 1999-June 2000 • "Chapel-en-le-Frith, Whaley Bridge, New Mills and Hayfield Advertiser" , June 1877-Sept.1881 • “High Peak Advertiser”, Oct. 1881 - Jul., 1937 • Ordnance Survey Maps, Derbyshire 1880, Derbyshire 1898 • Tithe Commission Apportionment - Beard, Ollersett, Whitle, Thornsett (+map) 1841 • Plans in connection with Railway Bills • Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway 1857 • Stockport, Disley and Whaley Bridge Railway 1857 • Disley and Hayfield Railway 1860 • Marple, New Mills and Hayfield Junction Railway 1860 • Disley and Hayfield Railway 1861 • Midland Railway (Rowsley to Buxton) 1862 • Midland Railway (New Mills widening) 1891 • Midland Railway (Chinley and New Mills widening) 1900 • Midland Railway (New Mills and Heaton Mersey Railway) 1897 • Census Microfilm 1841-1901 (Various local area) • 1992 Edition of the I.G.I. (England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Isle of Man, Channel Islands • Church and Chapel Records • New Mills Wesleyan Chapel, Baptisms 1794-1837 • New Mills Independent Chapel, Baptisms 1830-1837 • New Mills Independent Chapel, Burials 1832-1837 • Glossop Wesleyan Chapel, Baptisms 1813-1837 • Hayfield Chapelry and Parish Church Registers • Bethal Chapel, Hayfield, Baptisms 1903-1955 • Brookbottom Methodist Church 1874-1931 • Low Leighton Quaker Meeting House, New Mills • St.Georges Parish Church, New Mills • Index of Burials • Baptisms Jan.1888-Sept.1925 • Burials 1895-1949 • Marriages 1837-1947 • Coal Mining Account Book / New Mills and Bugsworth District 1711-1757 • Derbyshire Directories, 1808 - 1977 (New Mills entries are also available separately). -

Land Off Brook Hill Lane, Dunford Bridge, Barnsley, Sheffield

2019/1013 Applicant: National Grid Description: Planning application for National Grid's Visual Impact Provision (VIP) project involving the following works:1) Construction of a new sealing end compound, including permanent access; 2) Construction of a temporary haul road from Brook Hill Lane including widened bellmouth; 3) Construction of a temporary Trans Pennine Trail Diversion to be used for approximately 12 - 18 months; following construction approximately 410m of said diversion surface would be retained permanently; and 4) Erection of two bridges (one temporary and one permanent) along the Trans Pennine Trail diversion Site Address: Land off Brook Hill Lane, Dunford Bridge, Barnsley, Sheffield Site Description The site stretches from Dunford Bridge in the Peak District National Park to Wogden Foot LWS approximately 1.8km to the east. With the exception of the sealing end compounds at either end, the site is linear and broadly follows the route of the Trans Pennine Trail (TPT). At Dunford Bridge the site extends to the former rail tunnel entrance and includes the existing sealing end compound located behind properties on Don View. Beyond this is the TPT car park and the TPT itself which is a former rail line running from Dunford Bridge to Penistone; now utilised as a bridleway. The site takes in land adjacent the TPT along which a temporary diverted bridleway route is proposed. In addition, Wogden Foot, a Local Wildlife Site (LWS) located 1.8km to the east is included (in part) as the proposed location of a new sealing end compound; construction access to this from Windle Edge also forms part for the application. -

Peaks Sub-Region Climate Change Study

Peak Sub-Region Climate Change Study Focussing on the capacity and potential for renewables and low carbon technologies, incorporating a landscape sensitivity study of the area. Final Report July 2009 ! National Energy Foundation "#$ % &' !' ( # ) ( * )(+,$- " ,++++ ./.. Land Use Consultants 0%# 1 $2& " 3,+3,0 . *.4. CONTENTS )!5$ 6" 1 Executive Summary.................................................................................................... 7 2 Study Background and Brief ................................................................................... 11 !7*84'*/#* ............................................................................................. 94.............................................................................................................................. 4 /#* ................................................................................................................... ! 4# ................................................................................................................................. 6 * .................................................................................................................................... 0 4/#* ............................................................................................................. 0 *# ................................................................................... + 3 Policy Context.......................................................................................................... -

Culture Derbyshire Papers

Culture Derbyshire 9 December, 2.30pm at Hardwick Hall (1.30pm for the tour) 1. Apologies for absence 2. Minutes of meeting 25 September 2013 3. Matters arising Follow up on any partner actions re: Creative Places, Dadding About 4. Colliers’ Report on the Visitor Economy in Derbyshire Overview of initial findings D James Followed by Board discussion – how to maximise the benefits 5. New Destination Management Plan for Visit Peak and Derbyshire Powerpoint presentation and Board discussion D James 6. Olympic Legacy Presentation by Derbyshire Sport H Lever Outline of proposals for the Derbyshire ‘Summer of Cycling’ and discussion re: partner opportunities J Battye 7. Measuring Success: overview of performance management Presentation and brief report outlining initial principles JB/ R Jones for reporting performance to the Board and draft list of PIs Date and time of next meeting: Wednesday 26 March 2014, 2pm – 4pm at Creswell Crags, including a tour Possible Bring Forward Items: Grand Tour – project proposal DerbyShire 2015 proposals Summer of Cycling MINUTES of CULTURE DERBYSHIRE BOARD held at County Hall, Matlock on 25 September 2013. PRESENT Councillor Ellie Wilcox (DCC) in the Chair Joe Battye (DCC – Cultural and Community Services), Pauline Beswick (PDNPA), Nigel Caldwell (3D), Denise Edwards (The National Trust), Adam Lathbury (DCC – Conservation and Design), Kate Le Prevost (Arts Derbyshire), Martin Molloy (DCC – Strategic Director Cultural and Community Services), Rachael Rowe (Renishaw Hall), David Senior (National Tramway Museum), Councillor Geoff Stevens (DDDC), Anthony Streeten (English Heritage), Mark Suggitt (Derwent Valley Mills WHS), Councillor Ann Syrett (Bolsover District Council) and Anne Wright (DCC – Arts). Apologies for absence were submitted on behalf of Huw Davis (Derby University), Vanessa Harbar (Heritage Lottery Fund), David James (Visit Peak District), Robert Mayo (Welbeck Estate), David Leat, and Allison Thomas (DCC – Planning and Environment). -

High Speed Rail

House of Commons Transport Committee High Speed Rail Tenth Report of Session 2010–12 Volume III Additional written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be published 24 May, 7, 14, 21 and 28 June, 12 July, 6, 7 and 13 September and 11 October 2011 Published on 8 November 2011 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited The Transport Committee The Transport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Department for Transport and its Associate Public Bodies. Current membership Mrs Louise Ellman (Labour/Co-operative, Liverpool Riverside) (Chair) Steve Baker (Conservative, Wycombe) Jim Dobbin (Labour/Co-operative, Heywood and Middleton) Mr Tom Harris (Labour, Glasgow South) Julie Hilling (Labour, Bolton West) Kwasi Kwarteng (Conservative, Spelthorne) Mr John Leech (Liberal Democrat, Manchester Withington) Paul Maynard (Conservative, Blackpool North and Cleveleys) Iain Stewart (Conservative, Milton Keynes South) Graham Stringer (Labour, Blackley and Broughton) Julian Sturdy (Conservative, York Outer) The following were also members of the committee during the Parliament. Angie Bray (Conservative, Ealing Central and Acton) Lilian Greenwood (Labour, Nottingham South) Kelvin Hopkins (Labour, Luton North) Gavin Shuker (Labour/Co-operative, Luton South) Angela Smith (Labour, Penistone and Stocksbridge) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. -

D112 Lantern Pike from Hayfield

0 Miles 1 2 d112 Lantern Pike from Hayfield 0 Kilometres 1 2 3 The walk shown is for guidance only and should Hayfield is on the A624 Glossop to Chapel-en-le-Frith Road not be attempted without suitable maps. A steady climb to superb views Details Go W from the car park on the Sett Valley 2 From the summit go N & descend to rejoin Trail until it bends left to reach a road at a hand the PBW. Continue N (left) on the PBW Distance: 7.5km (43/4 miles) gate. Don't go through but go right descending bearing NNW at a faint fork to cross the grass Total Ascent: 274m (899ft) to a 2nd hand gate opposite a Tea Room. Go & reach a 6-way junction at a track. (1km) 3 Time: 2 /4 hrs Grade: 3 W (right) on the road over the River Sett. 3 Go ENE (right) on the track (signed - 'Car ® 1 Maps: OS Landranger 110 (1 /2 km) Meadow' & 'Brookhouses' to skirt round or OS Explorer Map™ OL1 1 Beyond the 1st terrace go NE (right) up a Blackshaw Farm & continue E for 500m. Start/Finish: Sett Valley Trail Car Park, cobbled lane (signed 'Pennine Bridleway (1/2 km) Hayfield, Derbyshire Lantern Pike'). Join a concrete track & continue 4 Leave the track & go S (right) on a path Grid Ref: SK036869 NE (straight on) to reach a road. Go E (right) (signed 'Little Hayfield'). Continue S through Sat Nav: N53.3790 W1.9474 briefly before continuing NNE (left) up a lane Hey Wood & then past some cottages. -

New Mills Buxton Long Eaton Glossop Derby Chesterfield

A61 To Berwick- Shepley To Leeds upon-Tweed A62 A628 A671 A6052 WEST A635 Pennine Bridleway National Trail Holmfirth Denby Dale Cudworth to Cumbria. A663 YORKSHIRE A616 A627(M) A635 A629 A670 A672 Barnsley A6024 A62 Holme B6106 Oldham A628 A635 Silkstone Uppermill A635 Tour de France Grasscroft Stage 2 Victoria Dodworth A669 A633 Silkstone ns Pe Common Tra nn ine Crow Trail S GREATER Millhouse H A62 Greenfield Edge M1 Wombwell E A628 To Hull and York I F l Green N i A627 F F MANCHESTER I I a R Hazelhead E D r M Penistone L A T Chesterfield D A Worsbrough O R e R Y R Dunford n O R A61 i A D A6024 N Bridge . n . Mossley D A O M60 E n T Oxspring A6195 A633 V 6 e A 1 G P N A628 Thurgoland A6023 I B6175 s NE N A M n L Langsett A6135 O W I S E Ashton- E RY R a Y R S M18r W Midhopestones Hoyland H B D T B N U . O A629 R T R R under- Woodhead N A60 O A Langsett E A1(M) L N C A670 Crowden T T MAL Pennine SA Y KI Lyne l A616 LTE W R S N Tr i Reservoir RGA OA T. A635 Bridleway an a Mexborough TE E D r D s T L P Holmebrook Valley A ennine T E L Chesterfield D O L T Torside Underbank S L T Swinton A A R S S A A I LT T ER T S G G A Rail Station E T A616 O E R H E Reservoir Reservoir ALB E N E R IO Wentworth N L E R R E Town A O L W A Y E R T Stalybridge D Conisbrough E I T Greenway S A t M D A662 Torside H S C A627 O L s N I A628 U Hall W O N E E L e O D R R E k S S r P Stocksbridge G O N N C R l N A ON o O n TI ail 6 s Y r A R E m E T e O n i E il N S e d . -

Peakland Guardian Autumn and Winter 2020

Peak District and South Yorkshire Peakland Guardian Autumn and Winter 2020 Peaklandguardian 1 In this issue… Notes from the CEO 3 Planning reforms – the wrong answers to the wrong questions 4 Planning Sheffield’s future 6 Success for the Loxley Valley 8 Hollin Busk 10 Owlthorpe Fields 10 Doncaster Local Plan 11 Longdendale – the long game 12 Save our Monsal Trail 13 New OfGEM pylon plans 13 Decarbonising transport 14 Hope Valley Climate Action 15 Hayfield’s solar farm project 16 Greener, Better, Faster 17 Party plans for gothic lodge 18 Britannia Mill, Buxworth 18 Hope Cement Works Quarry ©Tomo Thompson Business Sponsor Focus 19 Right to Roam 19 New trustees 20 We have been the same Welcome from the CEO Ethel’s legacy 21 CPRE branch since 1927 but since 2002 we’ve also Welcome to the latest edition of the Peakland Guardian. The articles in this edition New branding and website 21 been known as Friends cover a very broad range of our work over the last 6 months. The Trustees and I are Obituaries 22 of the Peak District. We’re now very grateful for the work that the staff and volunteers have continued to put in, in very Membership update 23 going back to our roots: Same charity. Same passion for our local difficult circumstances, in order to protect the landscapes of the Peak District and South CPRE Peak District and South Yorkshire promotes the countryside. Yorkshire. beauty, tranquility and diversity of the countryside across the Peak District and South Yorkshire. We work to protect and Over the last 6 months, the pandemic has had little impact on our workload, indeed enhance its unique landscapes for everyone to enjoy now Follow us on social we are exceptionally busy at the moment, however the pandemic has stopped almost and in the future. -

Chapel-En-Le-Frith the COPPICE a Stunning Setting for Beautiful Homes

Chapel-en-le-Frith THE COPPICE A stunning setting for beautiful homes Nestling in the heart of the captivating High Peak of Derbyshire, Chapel-en-le-Frith is a tranquil market town with a heritage stretching back to Norman times. Known as the ‘Capital of the Peak District’, the town lies on the edge of the Peak District National Park, famous for its spectacular landscape. From The Coppice development you can pick up a number of walking trails on your doorstep, including one which leads up to the nearby Eccles Pike and its magnificent 360 views. Alternatively, you can stroll down to the golf course to play a round in a striking rural setting or walk into the town centre to enjoy a coffee in one of the many independent cafés. People have been visiting this area for centuries and not just for the exquisite scenery: the area is well connected by commuter road and rail links to Buxton and Manchester, while the magnificent Chatsworth House, Haddon Hall and Hardwick Hall are all within easy reach. View from Eccles Pike Market Cross THE COPPICE Chapel-en-le-Frith Market Place Amidst the natural splendour of the High Peak area, The Coppice gives you access to the best of both worlds. The town has a distinct sense of identity but is large enough to provide all the amenities you need. You can wander through the weekly market held in the historic, cobbled Market Place, admire the elaborate decorations which accompany the June carnival, and choose to dine in one of Imagine the many restaurants and pubs. -

Appendix 6 High Peak Locality Public Health Plan 2017-18

A HEALTHY HIGH PEAK – HIGH PEAK LOCALITY PUBLIC HEALTH PLAN 2017/18 Demographic profile The High Peak is a Borough Council area in the North of Derbyshire. At the time of the 2011 Census it had a population of about 91,000 distributed across 208 square miles. The largest town is Buxton (population 22,000) and the second largest is Glossop (population 17,500). Key statistics 1. Two lower super output areas (LSOA) in Glossop (making up Gamesley ward) fall within the 10% most deprived in England and are the fifth and tenth most deprived LSOAs in Derbyshire ( IMD 2015) 2. Male life expectancy at birth in Gameseley is 76.3 years compared with 79.3 for both Derbyshire and England (ONS). For females it is 79.3 years compared with 83 for both Derbyshire and England. 3. The most recent ONS figures for Jobseeks Allowance claimants (Nov 2016) show that Gamesley in Glossop has the second highest level in Derbyshire with a rate of 2.2%. Whitfield ranked 9th worst (1.7%). The comparable figures for High Peak are 0.7%, Derbyshire 0.8% and England 1.1%. 4. In the High Peak, a higher percentage of Jobseekers Allowance claimants are long term unemployed (over 12 months) compared to county or national rates (35.4% in High Peak equating to 145 people compared to33.7% in Derbyshire and 31.2% England). 5. The rates of people on Employment Support Allowance and Incapacity Benefits (May 2016) in High Peak at 5.6% are below the Derbyshire (6.3%) and England (5.9%) rates but these mask specific areas where ESA rates are much higher.