Alternative Realities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hong Kong, 1941-1945

Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre 7 Tin Wan Praya Road Aberdeen Hong Kong © Ray Barman 2009 ISBN 978-962-209-976-0 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All photos, illustrations, and newspaper cuttings in this book are from the collection of the Barman family. Every effort has been made to track ownership and formal permission from the copyright holders. If there are any inadvertent omissions we apologize to those concerned, and ask that they contact us so that we can correct any oversight as soon as possible. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Secure On-line Ordering http://www.hkupress.org Printed and bound by Condor Production Ltd., Hong Kong, China. Contents Foreword for the Series ix About This Book xi Abbreviations xiii About the Author xvii Introduction 1 The Battle 5 Internment 93 Postscript 265 Appendices 269 Notes 293 Index 299 About the Author Charles Edward Barman was born at Canterbury, Kent in England on 14 May 1901, the eldest of four children. He was the son of a gardener, Richard Thomas, and Emily Barman from Tenterden, an area of Kent where many people of the Barman name still live. Charles had two brothers, Richard and George, and a younger sister, Elsie. As a boy, he attended the local primary school at Canterbury and attended services at the Cathedral. -

Hansard of the Former Legislative Council Then, I Note the Request Made by Many Honourable Members That Direct Elections Be Held for ADC Members

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 25 May 2011 10789 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 25 May 2011 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. 10790 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 25 May 2011 THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TIMOTHY FOK TSUN-TING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE AUDREY EU YUET-MEE, S.C., J.P. -

Historic Building Appraisal 1 Tsang Tai Uk Sha Tin, N.T

Historic Building Appraisal 1 Tsang Tai Uk Sha Tin, N.T. Tsang Tai Uk (曾大屋, literally the Big Mansion of the Tsang Family) is also Historical called Shan Ha Wai (山廈圍, literally, Walled Village at the Foothill). Its Interest construction was started in 1847 and completed in 1867. Measuring 45 metres by 137 metres, it was built by Tsang Koon-man (曾貫萬, 1808-1894), nicknamed Tsang Sam-li (曾三利), who was a Hakka (客家) originated from Wuhua (五華) of Guangdong (廣東) province which was famous for producing masons. He came to Hong Kong from Wuhua working as a quarryman at the age of 16 in Cha Kwo Ling (茶果嶺) and Shaukiwan (筲箕灣). He set up his quarry business in Shaukiwan having his shop called Sam Lee Quarry (三利石行). Due to the large demand for building stone when Hong Kong was developed as a city since it became a ceded territory of Britain in 1841, he made huge profit. He bought land in Sha Tin from the Tsangs and built the village. The completed village accommodated around 100 residential units for his family and descendents. It was a shelter of some 500 refugees during the Second World War and the name of Tsang Tai Uk has since been adopted. The sizable and huge fortified village is a typical Hakka three-hall-four-row Architectural (三堂四横) walled village. It is in a Qing (清) vernacular design having a Merit symmetrical layout with the main entrance, entrance hall, middle hall and main hall at the central axis. Two other entrances are to either side of the front wall. -

Intergenerational Play Space

“One from Hundred Thousand” Social Innovation Symposia Series Season 4 – Intergenerational Play Space Fitness Trail at Kowloon Park Information Pack Prepared by Jockey Club Design Institute for Social Innovation May 2019 Disclaimer All materials provided in this info pack is intended to give only a general information and contextual overview of the sites for reference by the participants of the One from Hundred Thousand Season Four Symposium. DISI specifically disclaims any liability incurred as a consequence of using any information given in this info pack. 1 CONTENTS OBJECTIVES and DEFINITIONS 2 Objective 2 Definitions 2 Why “Intergenerational Play Space”? 3 PROJECT SITE INFORMATION 4 Kowloon Park Overview 4 Site Overview 5 User behaviour 6 Opportunities & Constraints 7 INTERGENERATIONAL PLAY SPACE CONSIDERATIONS 8 PHOTO REFERENCE 10 RELATED NEWS AND ARTICLE LINKS 14 APPENDIX 15 APPENDIX I: BACKGROUND AND SITE HISTORY 15 APPENDIX II: LIST OF INDOOR AND OUTDOOR FACILITIES IN KOWLOON PARK 16 APPENDIX III: TRANSPORTATION 17 OBJECTIVES and DEFINITIONS Objective To co-design an intergenerational play space for the Fitness Trail at Kowloon Park Definitions ❏ Play space refers to an environment where play can take place ❏ Playgrounds, parks and privately owned public spaces (POPS) can all be play spaces 2 Why “Intergenerational Play Space”? Sources: WHO1, Civic Exchange2, HKPSI3, Civic Exchange4, Morita and Kobayashi5, Civic Exchange6, Civic Exchange7 1 World Health Organisation 2 Civic Exchange Open Space Opinion Survey 2018, p. 34 3 HKPSI Privately Owned Public Space Audit Report, p. 3 4 Civic Exchange Open Space Opinion Survey 2018, p. 79 5 Kumiko Morita, Minako Kobayashi, BMC Geriatrics. 2013. -

立法會cb(1)778/16-17(02)號文件

立法會CB(1)778/16-17(02)號文件 《古物及古蹟(暫定古蹟的宣布)(紅樓)公告》小組委員會 議員在 2017 年 3 月 31 日會議要求提供的資料 (1) 古物諮詢委員會(下稱「古諮會」)在 1981 年將紅樓評為 一級歷史建築的評估,以及古諮會及後檢視評級的相關 文件 古物諮詢委員會(下稱「古諮會」)先後在 1981 年、1985 年、1995 年、2009 年和 2011 年考慮紅樓的文物價值。古諮會 自 2005 年 9 月起,開放例會讓市民列席旁聽,並把公開會議 的討論文件和會議記錄上載古諮會網頁。由於在古諮會公開會 議前(即 2005 年 9 月前)的討論文件和會議記錄屬內部限閱文件, 因此只提供有關會議的摘要如下。 2. 古諮會自 1980 年起採用歷史建築評級制度:一級歷史 建築指具特別重要價值的建築物;二級歷史建築指具特別價值 的建築物;以及三級歷史建築指具若干價值的建築物。紅樓當 時被納入中式建築的名單內,其暫定評級為二級歷史建築。 3. 古諮會在 1981 年 1 月 13 日舉行的第 22 次會議上指出 紅樓的建築特色屬西式建築,並且認為應把紅樓評為一級歷史 建築。古諮會在 1981 年 3 月 31 日舉行的第 23 次會議上考慮 應否建議向古物事務監督根據《古物及古蹟條例》第 3(1)條把 紅樓宣布為法定古蹟。委員不支持宣布紅樓為法定古蹟,認為 紅樓與孫中山先生沒有直接關係。 4. 古諮會在 1985 年 4 月 30 日舉行的第 43 次會議上檢視 已評為一級歷史建築的情況。委員當時維持紅樓一級歷史建築 的級別。古諮會沒有建議把紅樓列為法定古蹟。 5. 古諮會在 1995 年 2 月 28 日舉行的第 85 次會議上檢視 古諮會早前給予紅樓的評級。當時對紅樓的文物價值的分析與 載於立法會參考資料摘要(檔號:DEVB/CHO/1B/CR/14/39)附件 B 的類同,包括難以考實紅樓的建築年份、未能確定紅樓與孫中 山先生領導的革命活動是否直接有關等。委員考慮到紅樓具備 1 1920 及 1930 年代建築物的特點;而現有紅樓與 1900-1905 年 測繪圖對照之下,其位置及形制並不相同。委員認為紅樓最早 不會建於 1920 年代之前,因此坊間流傳紅樓這幢建築本身(相 對青山農場整體而言)與革命活動直接有關的說法,未必屬實。 委員沒有調整古諮會早前對紅樓的評級。 6. 自 2005年,以下六項準則,即歷史價值、建築價值、組 合價值、社會價值和地區價值、保持原貌程度以及罕有程度, 一直被用作評估歷史建築的文物價值。古諮會對上一次覆檢紅 樓的評級,是在按上述評審準則為1 444幢歷史建築(包括紅樓) 評級時一併進行。當時已全面考慮所有研究所得有關紅樓的資 料,以及在公眾諮詢期間收到的意見及補充資料。在2009年 12 月 18日舉行的第141次會議上,古諮會參考獨立的歷史建築評 審小組的評審結果、根據六項評審準則對紅樓文物價值所得的 評估報告,並考慮集體回憶這個重要因素後,確認維持紅樓一 級歷史建築的級別。根據慣常做法,評估報告已上載古諮會網 頁。 7. 在 2011年 6月 15日舉行的第154次會議,古諮會應個別委 員提出審議把紅樓列為法定古蹟的建議。當時古諮會認為,鑑 於不能確定紅樓是否建於辛亥革命之前,因此紅樓與辛亥革命 相關的程度亦難以確定,除非有新證據證明紅樓與革命活動直 接有關,否則暫時不會考慮宣布紅樓為法定古蹟。 8. 按現行準則(即上文第 6 段提及的六項準則)以評審紅樓 文物價值的報告,請參閱立法會參考資料摘要( 檔號: DEVB/CHO/1B/CR/14/39)的附件 B。古諮會在 2009 年 12 月 18 日 舉行的第 141 次會議涉及紅樓的討論文件及會議記錄載於附 件 I,而 2011 年 6 月 15 日舉行的第 154 次會議涉及紅樓的會 議記錄載於附件 II。 (2) 就紅樓進行獨立評估 9. 按照現行制度,古諮會在參考獨立歷史建築評審小組就 個別建築物作出的文物價值評估,以及在公眾諮詢期間接獲市 民及相關建築物業主的意見及補充資料後,把個別歷史建築評 定為一級、二級、三級(或不予級別)。 2 10. -

Title Heritage Preservation Other Contributor(S)University of Hong Kong Author(S) Tsang, Wai-Yee; 曾惠怡 Citation Issued Date

Title Heritage preservation Other Contributor(s) University of Hong Kong Author(s) Tsang, Wai-yee; 曾惠怡 Citation Issued Date 2009 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10722/131001 Rights Creative Commons: Attribution 3.0 Hong Kong License THE UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG HERITAGE PRESERVATION: THE AFTER-USE OF MILITARY STRUCTURES IN HONG KONG A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ARCHITECTURE IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN SURVEYING DEPARTMENT OF REAL ESTATE AND CONSTRUCTION BY TSANG WAI YEE HONG KONG APRIL 2009 DECLARATION I declare that this dissertation represents my own work, except where due acknowledgement is made, and that it has not been previously included in a thesis, dissertation or report submitted to this University or to any other institution for a degree, diploma or other qualification. Signed: _______________________ Named: _______________________ Date: _______________________ - i - CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ......................................................................v LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................x ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..................................................................... xii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................. xiii ABSTRACT............................................................................................ xiv INTRODUCTION...................................................................................1 Research Context .................................................................................1 -

List of the 1444 Historic Buildings with Assessment Results

List of the 1,444 Historic Buildings with Assessment Results (as at 9 Sept 2021) Page 1 Proposed Year of Construction / Remarks Number Name and Address 名稱及地址 Ownership Grading Restoration 備註 Grade 1 confirmed on 18 Dec 2009 Tsang Tai Uk, Sha Tin, N.T. 新界沙田曾大屋 1 Private Built 1847-1867 1 二○○九年十二月十八日確定為一級歷史建築 Combined with numbers 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 as one item and accorded with The Wai was built between Kat Hing Wai, Shrine, Kam Tin, Yuen Long, Grade 1 collectively on 31 Aug 2010 新界元朗錦田吉慶圍神廳 1 Private 1465 and 1487, the wall 2 二○一○年八月三十一日確定與編號3、4、5、6和7合併為一項, N.T. was 1662-1722. 並整體評為一級歷史建築 The Wai was built between Combined with numbers 2, 4, 5, 6 and 7 as one item and accorded with Kat Hing Wai, Entrance Gate, Kam Tin, 1465 and 1487, the wall Grade 1 collectively on 31 Aug 2010 3 新界元朗錦田吉慶圍圍門 1 Private Yuen Long, N.T. was 1662-1722, alias Fui 二○一○年八月三十一日確定與編號2、4、5、6和7合併為一項, Sha Wai (灰沙圍). 並整體評為一級歷史建築 The Wai was built between Combined with numbers 2, 3, 5, 6 and 7 as one item and accorded with Kat Hing Wai, Watchtower (northwest) and 新界元朗錦田吉慶圍炮樓 1465 and 1487, the wall Grade 1 collectively on 31 Aug 2010 4 1 Private Enclosing Walls, Kam Tin, Yuen Long, N.T. (西北)及圍牆 was 1662-1722, alias Fui 二○一○年八月三十一日確定與編號2、3、5、6和7合併為一項, Sha Wai (灰沙圍). 並整體評為一級歷史建築 The Wai was built between Combined with numbers 2, 3, 4, 6 and 7 as one item and accorded with Kat Hing Wai, Watchtower (northeast) and 新界元朗錦田吉慶圍炮樓 1465 and 1487, the wall Grade 1 collectively on 31 Aug 2010 5 1 Private Enclosing Walls, Kam Tin, Yuen Long, N.T. -

Surveying and Built Environment Vol 24(1), 8-36 December 2015 ISSN 1816-9554

Information All rights reserved. No part of this Journal may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the permission of the Hong Kong Institute of Surveyors. Contents of the Journal do not necessarily reflect the views or opinion of the Institute and no liability is accepted in relation thereto. Copyright © 2015 The Hong Kong Institute of Surveyors ISSN 1816-9554 總辦事處 Head Office 香港上環干諾道中111號永安中心12樓1205室 Room 1205, 12/F Wing On Centre, 111 Connaught Road Central, Sheung Wan, Hong Kong Telephone 電話: 2526 3679 Fax 傳真: 2868 4612 E-mail 電郵: [email protected] Web Site 網址: www.hkis.org.hk 北京辦事處 Beijing Office 中國北京市海淀區高樑橋斜街59號院1號樓 中坤大廈6層616室 (郵編:100044) Room 616, 6/F, Zhongkun Plaza, No.59 Gaoliangqiaoxiejie, No.1 yard, Haidian District, Beijing, China, 100044 Telephone 電話: 86 (10) 8219 1069 Fax 傳真: 86 (10) 8219 1050 E-mail 電郵: [email protected] Web Site 網址: www.hkis.org.hk Editorial Board Honorary Editor Sr Dick N.C. Kwok Professor Andrew Y.T. Leung The Hong Kong Institute of Surveyors Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering Hong Kong SAR, People’s Republic of China City University of Hong Kong Hong Kong SAR, People’s Republic of China Chairman and Editor-in-Chief Sr Professor K.W. Chau Sr Professor S.M. Lo Department of Real Estate and Construction Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering The University of Hong Kong City University of Hong Kong Hong Kong SAR, People’s Republic of China Hong Kong SAR, People’s Republic of China Sr Professor Esmond C.M. -

Gender As Spatial Identity Gender Strategizing in Postcolonial and Neocolonial Hong Kong

020 Gender as Spatial Identity Gender strategizing in postcolonial and neocolonial Hong Kong Leon Buker Gerhard Bruyns A photo essay exploring the how gender identity is 100—119 deliberately constructed through social positioning within the urban landscape of Hong Kong. Hong Kong has always had a binary identity, which continues through from the postcolonial to the neocolonial. This creates layers of additional complexity around gender identity, which is explored in terms of performativity and authenticity through both the heterosexual fluidity of foreign domestic workers and through homosexual tactics of local men, within a public park in Hong Kong. By rejecting the past through a politics of disappearance, previous boundaries around fluidity, repression, and suppression continue to influence the present in a volatile neocolonial context opening questions around what is an authentic performance of self. #hong kong #postcolonial #neocolonial #performativity #authenticity Leon Buker & Gerhard Bruyns . Gender as Spatial Identity | 101 This photo essay explores the manner in which commercial venture. In general, the city park is not gender identity is constructed as deliberate conceived as belonging to either gender, although instances of spatial positioning in the dense urban it could be postulated that as a relatively inclusive landscape of Hong Kong. The images are drawn (family) space, and a space more orientated to from a collection, Do You Know Where the Birds Are tactical interaction than strategic, it is more (2018), created by Liao Jiaming ( 廖家明), the City feminine than masculine. And in this vein, it can be University of Hong Kong. Both text and images claimed the shift from barracks to park is, on one elaborate on the complexity of contemporary level, a shift along the continuum from masculinity gender practices, in both the postcolonial1 – British towards femininity. -

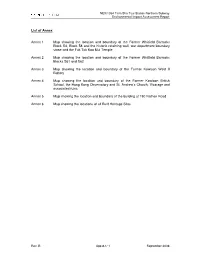

List of Annex Annex 1 Map Showing the Location and Boundary of the Former Whitfield Barracks Block S4, Block 58 and the Historic

NEX/1034 Tsim Sha Tsui Station Northern Subway Environmental Impact Assessment Report List of Annex Annex 1 Map showing the location and boundary of the Former Whitfield Barracks Block S4, Block 58 and the historic retaining wall, war department boundary stone and the Fuk Tak Koo Mui Temple Annex 2 Map showing the location and boundary of the Former Whitfield Barracks Blocks S61 and S62 Annex 3 Map showing the location and boundary of the Former Kowloon West II Battery Annex 4 Map showing the location and boundary of the Former Kowloon British School, the Hong Kong Observatory and St. Andrew’s Church, Vicarage and associated ruins Annex 5 Map showing the location and boundary of the building at 190 Nathan Road Annex 6 Map showing the locations of all Built Heritage Sites Rev. B App 8.1/ 1 September 2008 NEX/1034 Tsim Sha Tsui Station Northern Subway Environmental Impact Assessment Report Annex 1 Map showing the location and boundary of the Former Whitfield Barracks Block S4, Block 58 and the historic retaining wall, war department boundary stone and the Fuk Tak Koo Mui Temple Section Built Section Built in 1901 in 1996 Rev. B App 8.1/ 2 Aug 2008 NEX/1034 Tsim Sha Tsui Station Northern Subway Environmental Impact Assessment Report Annex 2 Map showing the location and boundary of the Former Whitfield Barracks Blocks S61 and S62 Rev. B App 8.1/ 3 Aug 2008 NEX/1034 Tsim Sha Tsui Station Northern Subway Environmental Impact Assessment Report Annex 3 Map showing the location and boundary of the Former Kowloon West II Battery Rev. -

About This Report 第 1 頁,共 1 頁

ArchSD Sustainability Report 2006 - About this Report 第 1 頁,共 1 頁 About this Report Scope of the Report We are delighted to introduce the Sustainability Report 2006 of Architectural Services Department (ArchSD), the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). It is our third consecutive annual sustainability report which gives details on our triple bottom line accomplishments between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2005. This online report presents an overview of our performance in the past year and illustrates how we have worked to uphold our mission and values, as well as our performance in addressing our economic, social and environmental responsibilities. The formulation of this report content is a joint effort of the Integrated Management Committee comprising ArchSD staff in various divisions and functions. Data are presented as absolute figures and, for priority issues, normalised into comparable terms where appropriate and practicable. Quantitative data are presented for all our six branches, excluding data from contractors and suppliers, unless otherwise stated. Qualitative information covers all our direct activities unless otherwise stated. Financial data is recorded according to financial year ended 31 March 2006 . All monetary values are in Hong Kong Dollar. The Report follows the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) G3 Guidelines (published in October 2006) and the Sector Supplement for Public Agencies (published in March 2005). A GRI Content Index is provided to facilitate referencing. http://www.archsd.gov.hk/english/reports/sustain_report_2006/e/about_this_report_text1.html 2007/5/30 ArchSD Sustainability Report 2006 - Message from Our Director 第 1 頁,共 2 頁 Message from Our Director Dear Readers, We are pleased to present our Sustainability Report 2006 to you. -

Asian Revitalization

ASIAN REVITALIZATION ADAPTIVE REUSE in HONG KONG, SHANGHAI, and SINGAPORE Edited by Katie Cummer and Lynne D. DiStefano Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong https://hkupress.hku.hk © 2021 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8528-55-4 (Hardback) ISBN 978-988-8528-56-1 (Paperback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Hang Tai Printing Co., Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Acknowledgments vii List of Contributors viii Adaptive Reuse: Introduction 1 Lynne D. DiStefano Essays Adaptive Reuse within Urban Areas 13 Michael Turner Cultural Heritage as a Driver for Sustainable Cities 18 Ester van Steekelenburg Measuring the Impacts: Making a Case for the Adaptive Reuse of Heritage Buildings 32 Donovan Rypkema Adaptive Reuse and Regional Best Practice 38 Lavina Ahuja New Lease of Life: The Evolution of Adaptive Reuse in Hong Kong 45 Katie Cummer, Ho Yin Lee, and Lynne D. DiStefano Hong Kong Timeline 63 Fredo Cheung and Ho Yin Lee Adaptive Reuse: Reincarnation of Heritage Conservation and Its Evolution in Shanghai 66 Hugo Chan and Ho Yin Lee Shanghai Timeline 82 Hugo Chan and Ho Yin Lee “Adapt and Survive”: