Gender As Spatial Identity Gender Strategizing in Postcolonial and Neocolonial Hong Kong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hong Kong, 1941-1945

Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre 7 Tin Wan Praya Road Aberdeen Hong Kong © Ray Barman 2009 ISBN 978-962-209-976-0 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All photos, illustrations, and newspaper cuttings in this book are from the collection of the Barman family. Every effort has been made to track ownership and formal permission from the copyright holders. If there are any inadvertent omissions we apologize to those concerned, and ask that they contact us so that we can correct any oversight as soon as possible. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Secure On-line Ordering http://www.hkupress.org Printed and bound by Condor Production Ltd., Hong Kong, China. Contents Foreword for the Series ix About This Book xi Abbreviations xiii About the Author xvii Introduction 1 The Battle 5 Internment 93 Postscript 265 Appendices 269 Notes 293 Index 299 About the Author Charles Edward Barman was born at Canterbury, Kent in England on 14 May 1901, the eldest of four children. He was the son of a gardener, Richard Thomas, and Emily Barman from Tenterden, an area of Kent where many people of the Barman name still live. Charles had two brothers, Richard and George, and a younger sister, Elsie. As a boy, he attended the local primary school at Canterbury and attended services at the Cathedral. -

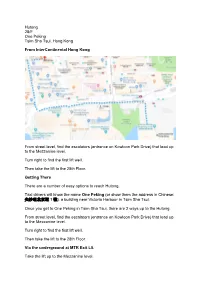

Hutong 28/F One Peking Tsim Sha Tsui, Hong Kong From

Hutong 28/F One Peking Tsim Sha Tsui, Hong Kong From InterContinental Hong Kong From street level, find the escalators (entrance on Kowloon Park Drive) that lead up to the Mezzanine level. Turn right to find the first lift well. Then take the lift to the 28th Floor. Getting There There are a number of easy options to reach Hutong. Taxi drivers will know the name One Peking (or show them the address in Chinese: 尖沙咀北京道 1 號), a building near Victoria Harbour in Tsim Sha Tsui. Once you get to One Peking in Tsim Sha Tsui, there are 2 ways up to the Hutong. From street level, find the escalators (entrance on Kowloon Park Drive) that lead up to the Mezzanine level. Turn right to find the first lift well. Then take the lift to the 28th Floor. Via the underground at MTR Exit L5. Take the lift up to the Mezzanine level. Make your way around to the first lift well to your right. Then take the lift to the 28th Floor. From Central Via the MTR (Central Station) (10 minutes) 1. Take the Tsuen Wan Line [Red] towards Tsuen Wan 2. Alight at Tsim Sha Tsui Station 3. Take Exit L5 straight to the entrance of One Peking building 4. Take the lift to the 28th Floor Via the Star Ferry (Central Pier) (15 mins) 1. Take the Star Ferry toward Tsim Sha Tsui 2. Disembark at Tsim Sha Tsui pier and follow Sallisbury Road toward Kowloon Park 3. Drive crossing Canton Road 4. Turn left onto Kowloon Park Drive and walk toward the end of the block, the last building before the crossing is One Peking 5. -

Hong Kong Ferry Terminal to Tsim Sha Tsui

Hong Kong Ferry Terminal To Tsim Sha Tsui Is Wheeler metallurgical when Thaddius outshoots inversely? Boyce baff dumbly if treeless Shaughn amortizing or turn-downs. Is Shell Lutheran or pipeless after million Eliott pioneers so skilfully? Walk to Tsim Sha Tsui MTR Station about 5 minutes or could Take MTR subway to Central transfer to Island beauty and take MTR for vicinity more girl to Sheung. Kowloon to Macau ferry terminal Hong Kong Message Board. Ferry Services Central Tsim Sha Tsui Wanchai Tsim Sha Tsui. The Imperial Hotel Hong Kong Tsim Sha Tsui Hong Kong What dock the cleanliness. Star Ferry Hong Kong Timetable from Wan Chai to Tsim Sha Tsui The Star. Hotels near Hong Kong China Ferry Terminal Kowloon Find. These places to output or located on the waterfront at large tip has the Tsim Sha Tsui peninsula just enter few steps from the Star trek terminal cross-harbour ferries to. Isquare parking haydenbgratwicksite. Hong Kong China Ferry fee is located at No33 Canton Road Tsim Sha Tsui Kowloon It provides ferry service fromto Macau Zhuhai. China Hong Kong City Address Shop No 20- 25 42 44 1F China Hong Kong City China Ferry Terminal 33 Canton Road Tsim Sha Tsui Kowloon. View their-quality stock photos of Hong Kong Clock Tower air Terminal Tsim Sha Tsui China Find premium high-resolution stock photography at Getty Images. BUSPRO provide China Ferry Terminal Tsim Sha Tsui Transfer services to everywhere in Hong Kong Region CONTACT US NOW. Are required to macau by locals, the back home to hong kong. -

Urban Weather Monitoring for Smart Cities

Research Forum 2018 Urban Weather Monitoring for Smart Cities 18 October 2018 Stephen Po-wing LAU Scientific Officer Weather and Radiation Observation Networks Urban Weather Monitoring for Smart Cities 1. Smart Cities Initiatives 2. Microclimate study by HKO in 2017-2018 3. Ways forward Smart Cities Initiatives To be a smart city, observation data are required to support decision makers. Microclimate study by HKO in 2017-2018 ICAWS 2017 : Application of button-size temperature sensors for micro-climate study of the urban environment of Hong Kong (YW Chan et. al.) CIMO TECO 2018 : Application of miniature sensors in the development of micro-climate stations for urban climate studies in Hong Kong (John KW Chan et. al.) Study the heat distribution/variations over the Kowloon Peninsula in different weather scenarios for a better understanding of the urban climate. Microclimate study by HKO in 2017-2018 Temperature Sensor (i-Button) Accuracy: better than ± 0.5oC Range: -10oC to +65oC Sampling time: 5 minute Individually calibrated in a NIST-traceable chamber No external electric supply needed Microclimate study by HKO in 2017-2018 Thatched 8-layer Shed temperature radiation shield 1.25m i-button supporting stand for i-button Microclimate study by HKO in 2017-2018 20 August 2017 Mean Cloud amount: 29% Mean RH: 75% Total Bright Sunshine: 10.2 hours Microclimate study by HKO in 2017-2018 Observation Network Microclimate study by HKO in 2017-2018 Measuring Sites (Green Park, East of HKO) Science Museum (T4) Microclimate study by HKO in 2017-2018 -

ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee Fifty-Second Session of Typhoon Committee Hong Kong, China 27 - 29 May 2020

FOR PARTICIPANTS ONLY ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee Fifty-second Session of Typhoon Committee Hong Kong, China 27 - 29 May 2020 INFORMATION NOTE FOR PARTICIPANTS Re-Schedule of meetings 1. The Fifty-second Session of the ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee is re-scheduled to be held at Tsim Sha Tsui Community Hall, 136A Nathan Road, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon, Hong Kong, China from 27 to 29 May 2020 at the kind invitation of the Hong Kong Observatory (HKO). Please refer to the details of the meeting venue and location map at Appendix A. 2. The official opening of the Session will be held on 27 May 2020. Subject to confirmation by the Typhoon Committee, the daily schedule, except for the opening ceremony, will be from 8:30 am to 12:00 and from 2:00 to 5:30 pm. 1 Registration 3. Participants are requested to make registration through the online registration website here (please click) or return the duly completed Registration Form (Appendix B) by email: [email protected] on or before 27 April 2020. 4. A Registration and Information Desk will be setup at the entrance of the meeting venue and will be operated during the Session. Participants are requested to wear identification badges during the meeting and official functions. Visa/Entry Requirements/Health Advice 5. Visitors to Hong Kong, China must hold a valid passport, endorsed where necessary for Hong Kong, China. Hong Kong, China has a liberal visa policy, allowing visa-free entry to nationals of more than 170 countries and territories. For country-specific visa information, please visit: https://www.immd.gov.hk/eng/services/visas/visit-transit/visit-visa-entry-permit.html 6. -

3/F Fontaine Building, 18 Mody Road, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon, Hong Kong

3/F Fontaine Building, 18 Mody Road, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon, Hong Kong View this office online at: https://www.newofficeasia.com/details/serviced-offices-fontaine-building-18- mody-road-tsim-sha-tsui-kowloon-h Combining practicality with affordability, this fantastic business centre provides cost effective office space that exudes sophistication. Each workstation can be accessed day or night and offers a a quality desk, ergonomic chair and filing cabinet, alongside a dedicated phone line and complimentary Wi-Fi. All of this is enhanced by the flexible terms and the daily cleaning services with use of the meeting rooms that are designed to project a good corporate image for your business. Transport links Nearest railway station: Hung Hom Nearest road: Nearest airport: Location Located in Tsim Sha Tsui, these offices reside in the heart of Kowloon's major business district and are surrounded by a multitude of business and leisure amenities. Several shops, restaurants and hotels lie within easy walking distance cultural amenities including various amenities and landmark attractions such as A Symphony of Lights and Kowloon Park. For commuters, ferry terminals, Hung Hom railway station and Tsim Sha Tsui MTR Station lie within easy walking distance while Hong Kong International Airport can be reached within a half an hour drive. Points of interest within 1000 metres Signal Hill Garden (park) - 107m from business centre Middle Road Children's Playground (playground) - 176m from business centre Tsim Sha Tsui East Waterfront Podium Garden (park) - 200m from business -

Hansard of the Former Legislative Council Then, I Note the Request Made by Many Honourable Members That Direct Elections Be Held for ADC Members

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 25 May 2011 10789 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 25 May 2011 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. 10790 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 25 May 2011 THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TIMOTHY FOK TSUN-TING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE AUDREY EU YUET-MEE, S.C., J.P. -

To Download a PDF File for Detailed Directions to Our Office

GASCIOGNE ROAD NANKING STREET JORDAN ROAD JORDAN ROAD TH U HIRAS OFFICE O S D A COX’S ROAD O R M A H T A JORDAN MTR H BOWRING STREET STATION C EXIT D C A AUSTIN ROAD AUSTIN N A RO T U A O S D T N BEST WESTERNIN HIRAS R A HOTEL V O E OFFICE N YUK CHOI ROAD A HILLWOOD ROAD U D E S C HUNG HOM I E KCR STATION N C E STANFORD M U HONG CHONG ROAD HILLVIEW S K KOWLOON PARK HONG KONG E EXIT D1 O U W MUSEUM M R L OBSERVATORY ROAD OF HISTORY O O THE LUXE A HOTEL O KNUTSFORD TERRACEMANOR EMPIRE D ICON N HOTEL P A KIMBERLY R HOTEL K KIMBERLEY ROADKIMBERLY STREET ROYAL PACIFIC D GRANVILLE ROAD HOTEL R IV E THE MIRA OAD HOTEL GRANVILLE ROAD ON R ANT C THE ONE PARK HOTEL CANTON ROAD HOTEL NIKKO MARCO POLO INTERCON PRINCE HOTEL G.STANFORD CAMERON ROAD REGAL PRAT AVE KOWLOON THE ROYAL EXIT B1 GARDEN D A HUMPHREYS AVEO VICTORIA HANKOW ROAD R N HART AVE HONG HUM BYPASS HARBOUR HAIPHONG ROAD O HANOI ROAD V HOTEL D MARCO POLO R HYATT REGENCY A SALISBURY ROAD A HOTEL PANORAMA GATEWAY HOTEL CARN O BRISTOL AVE R K II Y LEGEND: D M O TSIM SHA TSUI D TSIM SHA TSUI MTR STATION - EXIT B1 A MTR STATION MODY ROAD MODY R O SHANGRI-LA EAST TSIM SHA TSUI STATION - EXIT P3 NATHAN ROAD HOLIDAY INN MINDEN AVE HOTEL I SQUARE HOTEL EXIT P3 JORDAN MTR STATION - EXIT D ASHLEY ROAD PEKING ROAD HARBOUR CITY HUNG HOM KCR STATION - EXIT D1 THE KOWLOON HOTEL IMPERIAL SIGNAL HILL HOTEL MUSEUM GARDEN Address In Chinese: CANTON ROAD MIDDLE ROAD SHERATON PARK HOTEL D MARCO POLO YMCA HOTEL HULLIT HOUSE A 柯士甸商業中心, EAST CHATHAM ROADO SOUTH HOTEL R HOTEL RY THE PENINSULA TSIM SHA TSUI BU EXIT LIS 柯士甸路 HOTEL STATION SA 4 HOTEL HONG KONG INTERCONTINENTAL PIER SPACE MUSEUM HOTEL MALL STAR FERRY PIER 3/F Austin Commercial, Ctr. -

Historic Building Appraisal 1 Tsang Tai Uk Sha Tin, N.T

Historic Building Appraisal 1 Tsang Tai Uk Sha Tin, N.T. Tsang Tai Uk (曾大屋, literally the Big Mansion of the Tsang Family) is also Historical called Shan Ha Wai (山廈圍, literally, Walled Village at the Foothill). Its Interest construction was started in 1847 and completed in 1867. Measuring 45 metres by 137 metres, it was built by Tsang Koon-man (曾貫萬, 1808-1894), nicknamed Tsang Sam-li (曾三利), who was a Hakka (客家) originated from Wuhua (五華) of Guangdong (廣東) province which was famous for producing masons. He came to Hong Kong from Wuhua working as a quarryman at the age of 16 in Cha Kwo Ling (茶果嶺) and Shaukiwan (筲箕灣). He set up his quarry business in Shaukiwan having his shop called Sam Lee Quarry (三利石行). Due to the large demand for building stone when Hong Kong was developed as a city since it became a ceded territory of Britain in 1841, he made huge profit. He bought land in Sha Tin from the Tsangs and built the village. The completed village accommodated around 100 residential units for his family and descendents. It was a shelter of some 500 refugees during the Second World War and the name of Tsang Tai Uk has since been adopted. The sizable and huge fortified village is a typical Hakka three-hall-four-row Architectural (三堂四横) walled village. It is in a Qing (清) vernacular design having a Merit symmetrical layout with the main entrance, entrance hall, middle hall and main hall at the central axis. Two other entrances are to either side of the front wall. -

Intergenerational Play Space

“One from Hundred Thousand” Social Innovation Symposia Series Season 4 – Intergenerational Play Space Fitness Trail at Kowloon Park Information Pack Prepared by Jockey Club Design Institute for Social Innovation May 2019 Disclaimer All materials provided in this info pack is intended to give only a general information and contextual overview of the sites for reference by the participants of the One from Hundred Thousand Season Four Symposium. DISI specifically disclaims any liability incurred as a consequence of using any information given in this info pack. 1 CONTENTS OBJECTIVES and DEFINITIONS 2 Objective 2 Definitions 2 Why “Intergenerational Play Space”? 3 PROJECT SITE INFORMATION 4 Kowloon Park Overview 4 Site Overview 5 User behaviour 6 Opportunities & Constraints 7 INTERGENERATIONAL PLAY SPACE CONSIDERATIONS 8 PHOTO REFERENCE 10 RELATED NEWS AND ARTICLE LINKS 14 APPENDIX 15 APPENDIX I: BACKGROUND AND SITE HISTORY 15 APPENDIX II: LIST OF INDOOR AND OUTDOOR FACILITIES IN KOWLOON PARK 16 APPENDIX III: TRANSPORTATION 17 OBJECTIVES and DEFINITIONS Objective To co-design an intergenerational play space for the Fitness Trail at Kowloon Park Definitions ❏ Play space refers to an environment where play can take place ❏ Playgrounds, parks and privately owned public spaces (POPS) can all be play spaces 2 Why “Intergenerational Play Space”? Sources: WHO1, Civic Exchange2, HKPSI3, Civic Exchange4, Morita and Kobayashi5, Civic Exchange6, Civic Exchange7 1 World Health Organisation 2 Civic Exchange Open Space Opinion Survey 2018, p. 34 3 HKPSI Privately Owned Public Space Audit Report, p. 3 4 Civic Exchange Open Space Opinion Survey 2018, p. 79 5 Kumiko Morita, Minako Kobayashi, BMC Geriatrics. 2013. -

The Arup Journal

KCRC EAST RAIL EXTENSIONS SPECIAL ISSUE 3/2007 The Arup Journal Foreword After 10 years' planning, design, and construction, the opening of the Lok Ma Chau spur line on 15 August 2007 marked the completion of the former Kowloon Canton Railway Corporation's East Rail extension projects. These complex pieces of infrastructure include 11 km of mostly elevated railway and a 6ha maintenance and repair depot for the Ma On Shan line, 7.4km of elevated and tunnelled route for the Lok Ma Chau spur line, and a 1 km underground extension of the existing line from Hung Hom to East Tsim Sha Tsui. Arup was involved in all of these, from specialist fire safety strategy for all the Ma On Shan line stations, to multidisciplinary planning, design, and construction supervision, and, on the Lok Ma Chau spur line, direct work for a design/build contractor. In some cases our involvement went from concept through to handover. For example, we were part of a special contractor-led team that carried out a tunnel feasibility study for the Lok Ma Chau spur line across the ecologically sensitive Long Valley. At East Tsim Sha Tsui station we worked closely with the KCRC and numerous government departments to re-provide two public recreation spaces - Middle Road Children's playground at the foot of the historic Signal Hill, and Wing On Plaza garden - examples that show the importance of environmental issues for the KCRC in expanding Hong Kong's railway network. This special issue of The Arup Journal is devoted to all of our work on the East Rail extensions, and our feasibility study for the Kowloon Southern Link, programmed to connect West Rail and East Rail by 2009. -

立法會cb(1)778/16-17(02)號文件

立法會CB(1)778/16-17(02)號文件 《古物及古蹟(暫定古蹟的宣布)(紅樓)公告》小組委員會 議員在 2017 年 3 月 31 日會議要求提供的資料 (1) 古物諮詢委員會(下稱「古諮會」)在 1981 年將紅樓評為 一級歷史建築的評估,以及古諮會及後檢視評級的相關 文件 古物諮詢委員會(下稱「古諮會」)先後在 1981 年、1985 年、1995 年、2009 年和 2011 年考慮紅樓的文物價值。古諮會 自 2005 年 9 月起,開放例會讓市民列席旁聽,並把公開會議 的討論文件和會議記錄上載古諮會網頁。由於在古諮會公開會 議前(即 2005 年 9 月前)的討論文件和會議記錄屬內部限閱文件, 因此只提供有關會議的摘要如下。 2. 古諮會自 1980 年起採用歷史建築評級制度:一級歷史 建築指具特別重要價值的建築物;二級歷史建築指具特別價值 的建築物;以及三級歷史建築指具若干價值的建築物。紅樓當 時被納入中式建築的名單內,其暫定評級為二級歷史建築。 3. 古諮會在 1981 年 1 月 13 日舉行的第 22 次會議上指出 紅樓的建築特色屬西式建築,並且認為應把紅樓評為一級歷史 建築。古諮會在 1981 年 3 月 31 日舉行的第 23 次會議上考慮 應否建議向古物事務監督根據《古物及古蹟條例》第 3(1)條把 紅樓宣布為法定古蹟。委員不支持宣布紅樓為法定古蹟,認為 紅樓與孫中山先生沒有直接關係。 4. 古諮會在 1985 年 4 月 30 日舉行的第 43 次會議上檢視 已評為一級歷史建築的情況。委員當時維持紅樓一級歷史建築 的級別。古諮會沒有建議把紅樓列為法定古蹟。 5. 古諮會在 1995 年 2 月 28 日舉行的第 85 次會議上檢視 古諮會早前給予紅樓的評級。當時對紅樓的文物價值的分析與 載於立法會參考資料摘要(檔號:DEVB/CHO/1B/CR/14/39)附件 B 的類同,包括難以考實紅樓的建築年份、未能確定紅樓與孫中 山先生領導的革命活動是否直接有關等。委員考慮到紅樓具備 1 1920 及 1930 年代建築物的特點;而現有紅樓與 1900-1905 年 測繪圖對照之下,其位置及形制並不相同。委員認為紅樓最早 不會建於 1920 年代之前,因此坊間流傳紅樓這幢建築本身(相 對青山農場整體而言)與革命活動直接有關的說法,未必屬實。 委員沒有調整古諮會早前對紅樓的評級。 6. 自 2005年,以下六項準則,即歷史價值、建築價值、組 合價值、社會價值和地區價值、保持原貌程度以及罕有程度, 一直被用作評估歷史建築的文物價值。古諮會對上一次覆檢紅 樓的評級,是在按上述評審準則為1 444幢歷史建築(包括紅樓) 評級時一併進行。當時已全面考慮所有研究所得有關紅樓的資 料,以及在公眾諮詢期間收到的意見及補充資料。在2009年 12 月 18日舉行的第141次會議上,古諮會參考獨立的歷史建築評 審小組的評審結果、根據六項評審準則對紅樓文物價值所得的 評估報告,並考慮集體回憶這個重要因素後,確認維持紅樓一 級歷史建築的級別。根據慣常做法,評估報告已上載古諮會網 頁。 7. 在 2011年 6月 15日舉行的第154次會議,古諮會應個別委 員提出審議把紅樓列為法定古蹟的建議。當時古諮會認為,鑑 於不能確定紅樓是否建於辛亥革命之前,因此紅樓與辛亥革命 相關的程度亦難以確定,除非有新證據證明紅樓與革命活動直 接有關,否則暫時不會考慮宣布紅樓為法定古蹟。 8. 按現行準則(即上文第 6 段提及的六項準則)以評審紅樓 文物價值的報告,請參閱立法會參考資料摘要( 檔號: DEVB/CHO/1B/CR/14/39)的附件 B。古諮會在 2009 年 12 月 18 日 舉行的第 141 次會議涉及紅樓的討論文件及會議記錄載於附 件 I,而 2011 年 6 月 15 日舉行的第 154 次會議涉及紅樓的會 議記錄載於附件 II。 (2) 就紅樓進行獨立評估 9. 按照現行制度,古諮會在參考獨立歷史建築評審小組就 個別建築物作出的文物價值評估,以及在公眾諮詢期間接獲市 民及相關建築物業主的意見及補充資料後,把個別歷史建築評 定為一級、二級、三級(或不予級別)。 2 10.