Charles II Louis XIV and the Order of Malta.PDF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malta & Gozo Directions

DIRECTIONS Malta & Gozo Up-to-date DIRECTIONS Inspired IDEAS User-friendly MAPS A ROUGH GUIDES SERIES Malta & Gozo DIRECTIONS WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Victor Paul Borg NEW YORK • LONDON • DELHI www.roughguides.com 2 Tips for reading this e-book Your e-book Reader has many options for viewing and navigating through an e-book. Explore the dropdown menus and toolbar at the top and the status bar at the bottom of the display window to familiarize yourself with these. The following guidelines are provided to assist users who are not familiar with PDF files. For a complete user guide, see the Help menu of your Reader. • You can read the pages in this e-book one at a time, or as two pages facing each other, as in a regular book. To select how you’d like to view the pages, click on the View menu on the top panel and choose the Single Page, Continuous, Facing or Continuous – Facing option. • You can scroll through the pages or use the arrows at the top or bottom of the display window to turn pages. You can also type a page number into the status bar at the bottom and be taken directly there. Or else use the arrows or the PageUp and PageDown keys on your keyboard. • You can view thumbnail images of all the pages by clicking on the Thumbnail tab on the left. Clicking on the thumbnail of a particular page will take you there. • You can use the Zoom In and Zoom Out tools (magnifying glass) to magnify or reduce the print size: click on the tool, then enclose what you want to magnify or reduce in a rectangle. -

The Dutch Poet Elisabeth Hoofman and Her German Patrons

Chapter 6 Possibilities of Patronage: The Dutch Poet Elisabeth Hoofman and Her German Patrons Nina Geerdink Patronage was a common practice for many early modern authors, but it was a public activity involving engagement with politics, pol- iticians and the rich and famous, and we know of relatively few women writers who profited from the benefits of patronage. The system of patronage altered, however, during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and one particular case study brings to light some of the possibilities and difficulties of this system for women writers. Elisabeth Hoofman (1664– 1736) was a Dutch poet whose authorship was representative of that of many writing women around 1700: born in a rich family, she wrote poetry in order to establish and consolidate contacts in a wealthy circle of friends and family, refusing to publish any of her poems. Her authorship status seems to have changed, though, after she and her husband lost their fortune and turned to rich patrons to secure their living. The circle of people addressed in her poetry broadened to power- ful men from outside of her intimate network and she started to print- publish. In this chapter, Hoofman’s opportunities to contrib- ute to the family income as a woman writer along with her abili- ty and necessity to manage her reputation are analysed with and through her poetry. ∵ Traditionally, Renaissance literary patronage has been regarded as a relation- ship between authors and patrons within the context of court culture. Pa- tronised authors received pensions for their poetic work, which they could produce relatively autonomously, as long as their literary reputation reflect- ed on the court and its ruler(s), and as long as their literary products could on occasion be used to amuse these ruler(s) and their guests. -

Ambassadors to and from England

p.1: Prominent Foreigners. p.25: French hostages in England, 1559-1564. p.26: Other Foreigners in England. p.30: Refugees in England. p.33-85: Ambassadors to and from England. Prominent Foreigners. Principal suitors to the Queen: Archduke Charles of Austria: see ‘Emperors, Holy Roman’. France: King Charles IX; Henri, Duke of Anjou; François, Duke of Alençon. Sweden: King Eric XIV. Notable visitors to England: from Bohemia: Baron Waldstein (1600). from Denmark: Duke of Holstein (1560). from France: Duke of Alençon (1579, 1581-1582); Prince of Condé (1580); Duke of Biron (1601); Duke of Nevers (1602). from Germany: Duke Casimir (1579); Count Mompelgart (1592); Duke of Bavaria (1600); Duke of Stettin (1602). from Italy: Giordano Bruno (1583-1585); Orsino, Duke of Bracciano (1601). from Poland: Count Alasco (1583). from Portugal: Don Antonio, former King (1581, Refugee: 1585-1593). from Sweden: John Duke of Finland (1559-1560); Princess Cecilia (1565-1566). Bohemia; Denmark; Emperors, Holy Roman; France; Germans; Italians; Low Countries; Navarre; Papal State; Poland; Portugal; Russia; Savoy; Spain; Sweden; Transylvania; Turkey. Bohemia. Slavata, Baron Michael: 1576 April 26: in England, Philip Sidney’s friend; May 1: to leave. Slavata, Baron William (1572-1652): 1598 Aug 21: arrived in London with Paul Hentzner; Aug 27: at court; Sept 12: left for France. Waldstein, Baron (1581-1623): 1600 June 20: arrived, in London, sightseeing; June 29: met Queen at Greenwich Palace; June 30: his travels; July 16: in London; July 25: left for France. Also quoted: 1599 Aug 16; Beddington. Denmark. King Christian III (1503-1 Jan 1559): 1559 April 6: Queen Dorothy, widow, exchanged condolences with Elizabeth. -

Vincent (Ċensu) Tabone, an Ophthalmologist and a President Of

SPECIAL ARTICLE Vincent (C˙ ensu) Tabone, an Ophthalmologist and a President of the Republic of Malta Robert M. Feibel, MD incent Tabone may be unique in the history of ophthalmology. He practiced ophthal- mology for 40 years in his homeland, the Republic of Malta. During that time, he be- came well known as a pioneer in the international effort to eradicate trachoma world- wide. At age 53, he began a long and successful political career as a member of parliament, Vthen as a cabinet minister, and, finally, as the democratically elected president of the Republic. He was active in European diplomacy and made important contributions at the United Nations. He may be the only ophthalmologist who has made great contributions in the field of medicine and in the democratic development of his country. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(3):373-377 The Republic of Malta is an archipelago of Tabone received his medical degree and small islands in the center of the Mediter- a degree in pharmacy in 1937; he then be- ranean Sea, between Sicily and Tunisia. Vin- gan his practice as a general physician. As cent (C˙ ensu) Tabone was born on March was the custom at the time, he worked at a 30, 1913, on Gozo, the second largest of the pharmacy, where patients came to con- 3 islands of Malta.1 He was the youngest of sult with him. He remembers that his first 10 children. His father, a physician and sur- patient had conjunctivitis. Life as a gen- geon working as a governmental medical eral physician was demanding, and the pay officer, died when Tabone was only 9 years was low. -

Philipps-Universität Marburg

nblick wiges G 5 Bachacker Kläran- m h E o l d b o r n La 6 Blumengarten lage B Zu orch r Ewiges Tal L A ü Am c m Am k . W 189 Sc W d e Rote heid er A stei iß W a uf n e 184 e d n g aße ld e A. r - Grube r Lahn 303 ehung Grabenstr r J 209 Galgengrundau) ö ch t c g r Flieder- Ringstr. a h B g Grün- i straße 309 . schiebel n S . Grundschule r K d t - r m Michelbach G S o e (im . 6 . tsum v e r Ringstr r o r g r - M ß t t a r ß r n e O t s r S i i c S f > - g r e f r n e en e h h onn we r f c S g n o 226 e ü h r a l - i i elb u Mecklen- d h o k h e n l e r b A i Am Jäger- e d 199 t i r l T e h n e m t n 229 wäldchen h F S B ü ac e s 316 S e n der Görtzb M S I r n ic h M i W h tü n l m c S 246 l e p G a elstal Friedrich- e F Industriestr a W ü t l Fröbel-Str r m Rehbocks- r d r l b e l m ecke A a b Ernst-Lemmer-Straße a W i A P n h ß c e e e A e h h aß r trChristopho- r e r r Srusstraße - r a ge v c bur o S k Magde m < Caldern t e 283 r r . -

Towards an Economic History of Eighteenth Century Malta

~TOWARDS AN ECONOMIC HISTORY OF EIGHTEENTH CENTURY MALTA Buzzaccarini Gonzaga's Correspondence to the Venetian Magistracy of Trade 1754-1776. Victor Mallia-Milanes The restraining late medieval legacy of allegiance and dependency which the Knights of St. John inherited on settling in the tiny central Mediterranean island of Malta had never been compatihle with the Order's grand aspirations 1. The history of Malta's foreign relations from 1530 to 1798 is the story of the Order's conscious and protracted efforts to remove the negatIve structural and institutional forces which debarred growth and development in order to mOhil ize the positive forces which would lead to economic progress. It was a dif ficult task to break away from the pattern of politico-economic subjection - to powers like France and Spain to conditions which would reduce Malta's complete dependence on traditional markets, manufactures and capital. Veneto-Maltese mutual economic approaches during the eighteenth century were just one outstanding example of this complex process of economic 're orientation. It is my purpose here to examine these "approaches" within the broad framework of the island's economy as a whole and the conceptions of it entertained by the Venetian Magistracy of Trade - the Cinque Savi alla Mercanzia 2, My examination will draw heavily on the large collection of Mas similiano Buzzaccarini Gonzaga's orginal, manuscript despatches from Malta to the Cinque Savi 3. I BUZZACCARINI GONZAGA professed a Knight of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem on 20th January, The Man 1712 liZ. On 25th September, 1754 h~ was the first to be accredited Huomo On 21st April, 1776 Antonio Pous della Repubblica di Venezia to the sielgues, the Venetian Consul in Grandmaster's Court in Malta 13, and Malta 4, wrote to the Cinque Savi in on the morning of 4th December he Venice to tell them of the sad and arrived on the island in that capa sudden death of Buzzaccarini Gon city 14. -

The Self-Perception of Chronic Physical Incapacity Among the Labouring Poor

THE SELF-PERCEPTION OF CHRONIC PHYSICAL INCAPACITY AMONG THE LABOURING POOR. PAUPER NARRATIVES AND TERRITORIAL HOSPITALS IN EARLY MODERN RURAL GERMANY. BY LOUISE MARSHA GRAY A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of London. University College, London 2001 * 1W ) 2 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the experiences of the labouring poor who were suffering from chronic physical illnesses in the early modern period. Despite the popularity of institutional history among medical historians, the experiences of the sick poor themselves have hitherto been sorely neglected. Research into the motivation of the sick poor to petition for a place in a hospital to date has stemmed from a reliance upon administrative or statistical sources, such as patient lists. An over-reliance upon such documentation omits an awareness of the 'voice of the poor', and of their experiences of the realities of living with a chronic ailment. Research focusing upon the early modern period has been largely silent with regards to the specific ways in which a prospective patient viewed a hospital, and to the point in a sick person's life in which they would apply for admission into such an institution. This thesis hopes to rectif,r such a bias. Research for this thesis has centred on surviving pauper petitions, written by and on behalf of the rural labouring poor who sought admission into two territorial hospitals in Hesse, Germany. This study will examine the establishment of these hospitals at the onset of the Reformation, and will chart their history throughout the early modern period. Bureaucratic and administrative documentation will be contrasted to the pauper petitions to gain a wider and more nuanced view of the place of these hospitals within society. -

Volume 1. from the Reformation to the Thirty Years War, 1500-1648 Protestant Resistance – the Schmalkaldic League (1531/35)

Volume 1. From the Reformation to the Thirty Years War, 1500-1648 Protestant Resistance – The Schmalkaldic League (1531/35) Since the time of the Peasants’ War, the evangelical princes and city regimes had talked about forming a defensive military league to protect themselves, their lands, and their cities in the event that the Edict of Worms (which forbade their religion) were imposed on them by force. Early efforts failed because the leading southern cities refused to enter into an alliance with the princes, and, more importantly, because the evangelical party was split between the followers of Luther, on the one hand, and Zwingli, on the other, over the meaning of the Lord's Supper (Eucharist). But on April 19, 1529, the estates did in fact come together to protest the Diet of Speyer’s decision to enforce the Edict of Worms, and it was at this gathering that the name “Protestant” was born. Still, the intra-evangelical doctrinal dispute prevented the formation of an alliance for another eighteen months. After the Diet of Augsburg (1530) failed to reconcile the Catholic and evangelical parties of the Diet, the Saxon elector called the Protestant estates to a meeting in the small town of Schmalkalden in December 1530. There, under the leadership of the Saxon elector and Landgrave Philip of Hesse, an agreement was made; a related treaty was approved at a second meeting in February 1531 (A). On December 23, 1535, nearly five years later, twenty-three estates approved the constitution of the Schmalkaldic League (B). The constitution makes clear that the alliance, unprecedented in its geographical scope, nonetheless conformed in its political and military institutions to the customs of the German federations. -

The French Invasion of Malta: an Unpublished Account Grazio V

J The French Invasion of Malta: An Unpublished Account Grazio V. Ellul Antony: The .Shakespearean Colossus - Part U David Cremona ) Inorganic Complexes: An Introduction Alfred Vella Memoria e Poesia Verghlana Joseph Eynaud ) Maltese Literature in the Sixties Peter Serracino Inglott Moliere: L'Homme a la Conquete de l'ldeal Alfred Falzon ) Numb&!", 3 Spring 1978 Journal of the Upper Secondary School, Valetta Number 3 Spring 1978 Editorial Board: Chairman: V.F. Buhagiar M.A. (Loud.), Arts EdItor; V. Mallia-Milanes M.A. Science Editor: C. Eynaud B.Sc., Members: L.J. Scerri M.A., J. Zammit Ciantar B.A. \-------------------------------------------------------, FOR SCIENCE STUDENTS INTERNATIONAL YOUTH SCIENCE FORTNIGHT IN LONDON on THE IMPORTANCE OF SCIENCE IN SOLVING THE WORLD'S PROBLEMS Semi nars! demonstrations!fil m shows! discussions!lectu res! visits to research establishments, university departments, industrial plants/sightseeing, social activities!full-board accomodation at University of London halls of residence. 26 JULY - 9 AUGUST 1978 TRAVEL GRANTS made available by the Commonwealth Youth Exchange Council and the National Student Travel Foundation (Malta) may be applied for by any post O-Level student of Science aged 16 - 22 years. information and applications from: N.S.T.F. (M.) 220, ST. PAUL STREET, VALLETTA. Tel: 624983 THE FRENCH INVASION OF MALTA: AN UNPUBLISHED ACCOUNT Gra.zio V. EUul In June 1798, the Order of St. John surrendered Malta to Napoleon Bonaparte. Hitherto students of French Malta have mostly made use of two contemporary accounts - by Felice Cutajar 1 and Bosredon Ransi'jat 2. Another contemporary unpublished version is that of the Syracusan man of letters, the Rev. -

Germany and the Coming of the French Wars of Religion: Confession, Identity, and Transnational Relations

Germany and the Coming of the French Wars of Religion: Confession, Identity, and Transnational Relations Jonas A. M. van Tol Doctor of Philosophy University of York History February 2016 Abstract From its inception, the French Wars of Religion was a European phenomenon. The internationality of the conflict is most clearly illustrated by the Protestant princes who engaged militarily in France between 1567 and 1569. Due to the historiographical convention of approaching the French Wars of Religion as a national event, studied almost entirely separate from the history of the German Reformation, its transnational dimension has largely been ignored or misinterpreted. Using ten German Protestant princes as a case study, this thesis investigates the variety of factors that shaped German understandings of the French Wars of Religion and by extension German involvement in France. The princes’ rich and international network of correspondence together with the many German-language pamphlets about the Wars in France provide an insight into the ways in which the conflict was explained, debated, and interpreted. Applying a transnational interpretive framework, this thesis unravels the complex interplay between the personal, local, national, and international influences that together formed an individual’s understanding of the Wars of Religion. These interpretations were rooted in the longstanding personal and cultural connections between France and the Rhineland and strongly influenced by French diplomacy and propaganda. Moreover, they were conditioned by one’s precise position in a number of key religious debates, most notably the question of Lutheran-Reformed relations. These understandings changed as a result of a number pivotal European events that took place in 1566 and 1567 and the conspiracy theories they inspired. -

A Landscape Assessment Study of the South Gozo Fault Area Mariella Xuereb James Madison University

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Fall 12-18-2010 A landscape assessment study of the South Gozo Fault area Mariella Xuereb James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Xuereb, Mariella, "A landscape assessment study of the South Gozo Fault area" (2010). Masters Theses. 434. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/434 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Landscape Assessment Study of the South Gozo Fault Area Mariella Xuereb Master of Science in Sustainable Environmental Resource Management University of Malta 2010 A Landscape Assessment Study of the South Gozo Fault Area A dissertation presented in part fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Sustainable Environmental Resource Management Mariella Xuereb November 2010 Supervisor: Dr. Louis. F. Cassar Co-Supervisors: Ms. Elisabeth Conrad; Dr. Maria Papadakis University of Malta – James Madison University ii. This research work disclosed in this publication is partly funded by the Strategic Educational Pathways Scholarship (Malta). Operational Programme II – Cohesion Policy 2007-2013 Empowering People for More Jobs and a Better Quality of Life Training part-financed by the European Union European Social Fund Co-financing rate: 85% EU Funds; 15% National Funds Investing in your future iii. ABSTRACT Mariella Xuereb A Landscape Assessment Study of the South Gozo Fault Area The South Gozo Fault region features a heterogeneous landscape which extends from Ras il-Qala on the east, to „Mgarr ix-Xini‟ on the south-eastern littoral. -

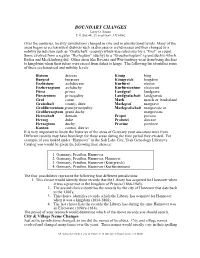

BOUNDARY CHANGES Larry O

BOUNDARY CHANGES Larry O. Jensen P. O. Box 441, Pleasant Grove, UT 84062 Over the centuries, locality jurisdictions changed in size and in jurisdictional levels. Many of the areas began as ecclesiastical districts such as dioceses or archdioceses and then changed to a nobility jurisdiction such as “Grafschaft” (county) which was ruled over by a “Graf” or count. Some evolved from a regular “Herzogtum” (duchy) to a “Grossherzogtum” (grand duchy) which Baden and Mecklenburg did. Other areas like Bavaria and Württemberg went from being duchies to kingdoms when their rulers were raised from dukes to kings. The following list identifies some of these ecclesiastical and nobility levels: Bistum diocese König king Burgraf burgrave Königreich kingdom Erzbistum archdiocese Kurfürst elector Erzherzogtum archduchy Kurfürstentum electorate Fürst prince Landgraf landgrave Fürstentum principality Landgrafschaft landgravate Graf count Mark march or borderland Grafschaft county, shire Markgraf margrave Großfürstentum grand principality Markgrafschaft margravate or Großherzogtum grand duchy margraviate Herrschaft domain Propst provost Herzog duke Probstei diocese Herzogtum duchy Provinz province Kanton canton, district It is very important to know the histories of the areas of Germany your ancestors were from. Different records may have been kept for these areas during the time period they existed. For example, if you looked under “Hannover” in the Salt Lake City, Utah Genealogy Library=s Catalog you would be given the following four choices: 1. Germany, Preußen, Hannover 2. Germany, Preußen, Hannover, Hannover 3. Germany, Preußen, Hannover (Königreich) 4. Germany, Preußen, Hannover (Kurfürstentum) The four possibilities represent the following four different jurisdictions: 1. This choice would identify those records that the Library has acquired for Hannover when it was a province in the kingdom of Prussia (1866-1945).