Dominant Metaphor in Maltese Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sicilian Revolution of 1848 As Seen from Malta

The Sicilian Revolution of 1848 as seen from Malta Alessia FACINEROSO, Ph.D. e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Following the Sicilian revolution of 1848, many italian intellectuals and politicalfiguresfound refuge in Malta where they made use ofthe Freedom ofthe Press to divulge their message ofunification to the mainland. Britain harboured hopes ofseizing Sicily to counterbalance French expansion in the Mediterranean and tended to support the legitimate authority rather than separatist ideals. Maltese newspapers reflected these opposing ideas. By mid-1849 the revolution was dead. Keywords: 1848 Sicilian revolution, Italian exiles, Freedom of the Press, Maltese newspapers. The outbreak of Sicilian revolution of 12 January 1848 was precisely what everyone in Malta had been expecting: for months, the press had followed the rebellious stirrings, the spread of letters and subversive papers, and the continuous movements of the British fleet in Sicilian harbours. A huge number of revolutionaries had already found refuge in Malta, I escaping from the Bourbons and anxious to participate in their country's momentous events. During their stay in the island, they shared their life experiences with other refugees; the freedom of the press that Malta obtained in 1839 - after a long struggle against the British authorities - gave them the possibility to give free play to audacious thoughts and to deliver them in writing to their 'distant' country. So, at the beginning of 1848, the papers were happy to announce the outbreak of the revolution: Le nOlizie che ci provengono dalla Sicilia sono consolanti per ta causa italiana .... Era if 12 del corrente, ed il rumore del cannone doveva annunziare al troppo soflerente papalo siciliano it giorno della nascifa def suo Re. -

History of Rotary Club Malta 1967 – 2007

THE HISTORY OF ROTARY CLUB MALTA 1967 – 2007 Compiled by Rotarian Robert von Brockdorff Dec 2008 © Robert Von Brockdorff 2008/9 Contents 1. Worldwide membership ................................................................................................................................ 1 2. Club Directory ................................................................................................................................................ 2 3. Club Newsletter ............................................................................................................................................. 2 4. Humour .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 5. Council decisions ............................................................................................................................................ 2 6. International Presidents in Malta .................................................................................................................. 2 7. District ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 8. Male Gender Membership ............................................................................................................................. 3 9. District Governors ......................................................................................................................................... -

Licensed ELT Schools in Malta and Gozo

A CLASS ACADEMY OF ENGLISH BELS GOZO EUROPEAN SCHOOL OF ENGLISH (ESE) INLINGUA SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES St. Catherine’s High School, Triq ta’ Doti, ESE Building, 60, Tigne Towers, Tigne Street, 11, Suffolk Road, Kercem, KCM 1721 Paceville Avenue, Sliema, SLM 3172 Mission Statement Pembroke, PBK 1901 Gozo St. Julian’s, STJ 3103 Tel: (+356) 2010 2000 Tel: (+356) 2137 4588 Tel: (+356) 2156 4333 Tel: (+356) 2137 3789 Email: [email protected] The mission of the ELT Council is to foster development in the ELT profession and sector. Malta Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Web: www.inlinguamalta.com can boast that both its ELT profession and sector are well structured and closely monitored, being Web: www.aclassenglish.com Web: www.belsmalta.com Web: www.ese-edu.com practically the only language-learning destination in the world with legislation that assures that every licensed school maintains a national quality standard. All this has resulted in rapid growth for INSTITUTE OF ENGLISH the sector. ACE ENGLISH MALTA BELS MALTA EXECUTIVE TRAINING LANGUAGE STUDIES Bay Street Complex, 550 West, St. Paul’s Street, INSTITUTE (ETI MALTA) Mattew Pulis Street, Level 4, St.George’s Bay, St. Paul’s Bay ESE Building, Sliema, SLM 3052 ELT Schools St. Julian’s, STJ 3311 Tel: (+356) 2755 5561 Paceville Avenue, Tel: (+356) 2132 0381 There are currently 37 licensed ELT Schools in Malta and Gozo. Malta can boast that both its ELT Tel: (+356) 2713 5135 Email: [email protected] St. Julian’s, STJ 3103 Email: [email protected] profession and sector are well structured and closely monitored, being the first and practically only Email: [email protected] Web: www.belsmalta.com Tel: (+356) 2379 6321 Web: www.ielsmalta.com language-learning destination in the world with legislation that assures that every licensed school Web: www.aceenglishmalta.com Email: [email protected] maintains a national quality standard. -

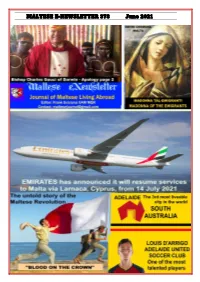

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 378 June 2021 1

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 378 June 2021 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 378 June 2021 Aboriginal survivors reach settlement with Church, Commonwealth cathnew.com Survivors of Aboriginal forced removal policies have signed a deal for compensation and apology 40 years after suffering sexual and physical abuse at the Garden Point Catholic Church mission on Melville Island, north of Darwin. Source: ABC News. “I’m happy, and I’m sad for the people who have gone already … we had a minute’s silence for them … but it’s been very tiring fighting for this for three years,” said Maxine Kunde, the leader Mgr Charles Gauci - Bishop of Darwin of a group of 42 survivors that took civil action against the church and Commonwealth in the Northern Territory Supreme Court. At age six, Ms Kunde, along with her brothers and sisters, was forcibly taken from her mother under the then-federal government’s policy of removing children of mixed descent from their parents. Garden Point survivors, many of whom travelled to Darwin from all over Australia, agreed yesterday to settle the case, and Maxine Kunde (ABC News/Tiffany Parker) received an informal apology from representatives of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart and the Daughters of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, in a private session.Ms Kunde said members of the group were looking forward to getting a formal public apology which they had been told would be delivered in a few weeks’ time. Darwin Bishop Charles Gauci said on behalf of the diocese he apologised to those who were abused at Garden Point. -

The Struggle to Preserve Language and Literature — Translated Literature | Bookwitty

4/6/2018 Malta: the Struggle to Preserve Language and Literature — Translated Literature | Bookwitty Malta: the Struggle to Preserve Language and Literature By Olivia Snaije July 24, 2017 Wit (13) Besides the fact that it’s a beautiful island in the middle of the Mediterranean, how much do we really know about Malta? You may remember it's where the Knights of Malta spent some time between the 16th and the 18th century. Comic book https://www.bookwitty.com/text/malta-the-struggle-to-preserve-language-and/596f7cb050cef766f8f236ab 1/11 4/6/2018 Malta: the Struggle to Preserve Language and Literature — Translated Literature | Bookwitty aficionados will be familiar with the fact that Joe Sacco was born in Malta. But did you know, for example, that in 2018 the island will be the European Capital of Culture? Or that every August a literature festival is held there? And that three Maltese authors, Immanuel Mifsud, Pierre J. Mejlak, and Walid Nabhan recently won the European Prize for Literature? The language they write in, of course, is Maltese, which is derived from an Arabic dialect that was spoken in Sicily and Spain during the Middle Ages. It sounds like Arabic with a smattering of Italian and English thrown in, and it is written in Latin script, making it the only Semitic language to be inscribed this way. A page from Il Cantilena https://www.bookwitty.com/text/malta-the-struggle-to-preserve-language-and/596f7cb050cef766f8f236ab 2/11 4/6/2018 Malta: the Struggle to Preserve Language and Literature — Translated Literature | Bookwitty A 15th century poem called “Il Cantilena”, by Petrus Caxaro is the earliest written document in Maltese that has been preserved. -

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 235 September 2018 1

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 235 September 2018 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 235 September 2018 President inaugurates meditation garden at Millennium Chapel President of Malta Marie-Louise Coleiro Preca officially inaugurated ‘The Word’ – the new meditation garden at the Millennium Chapel. President Coleiro Preca expressed her hope that this garden will be used by many people who are seeking refuge and peace in today’s uncertain world, and that they will be transformed by its atmosphere of contemplation and tranquillity. “Whilst I would like to commend the Millennium Chapel team for their dedication and hard work, in particular Fr Hilary Tagliaferro and his collaborators on this project, including Richard England, Duncan Polidano, Noel Attard, and Peter Calamatta, I am confident that the Millennium Chapel will continue to provide essential support and care for all the people who walk through its doors”, the President said. The Millennium Chapel The Millennium Chapel is run by a Foundation of lay volunteers and forms part of the Augustinian Province of Malta. Professional people and volunteers, called “Welcomers” are participating in the operation and day to day running of the Chapel and WoW (Wishing Others Well). The Chapel is open from 8.00 a.m. to 2.00 a.m. all the year round except Good Friday. You, too, may offer your time and talent to bring peace and love in the heart of the entertainment life of Malta, or may send a small contribution so that this mission may continue in the future. In the heart of the tourist and entertainment centre of Malta’s nightlife there stands an oasis of peace :- THE MILLENNIUM CHAPEL and WOW , (Wishing Others Well), These are two pit stops in the hustle and bustle of Paceville – considered the mecca of young people and foreign tourists who visit the Island of Malta. -

A Literary Translation in the Making

A LITERARY TRANSLATION IN THE MAKING An in-depth investigation into the process of a literary translation from French into Maltese CLAUDINE BORG Doctor of Philosophy ASTON UNIVERSITY October 2016 © Claudine Borg, 2016 Claudine Borg asserts her moral right to be identified as the author of this thesis This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without appropriate permission or acknowledgement. 1 ASTON UNIVERSITY Title: A literary translation in the making: an in-depth investigation into the process of a literary translation from French into Maltese Name: Claudine Borg Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Date: 2016 Thesis summary: Literary translation is a growing industry with thousands of texts being published every year. Yet, the work of literary translators still lacks visibility and the process behind the emergence of literary translations remains largely unexplored. In Translation Studies, literary translation was mostly examined from a product perspective and most process studies involved short non- literary texts. In view of this, the present study aims to contribute to Translation Studies by investigating in- depth how a literary translation comes into being, and how an experienced translator, Toni Aquilina, approached the task. It is particularly concerned with the decisions the translator makes during the process, the factors influencing these and their impact on the final translation. This project places the translator under the spotlight, centring upon his work and the process leading to it while at the same time exploring a scantily researched language pair: French to Maltese. -

Brian J. Dendle

Brian J. Dendle RICHARD ENGLAND, POET OF MALTA AND THE MIDDLE SEA To Richard England and Peter Serracino Inglott, in homage and friendship Richard England, the son of the Maltese architect Edwin Eng land Sant Fournier, was born in Sliema, Malta, 3 October 1937. He was educated at St. Edward's College (Cottonera, Malta), studied architecture at the (then) Royal University of Malta (1954-61) and at the Milan Polytechnic, and worked as a stu dent-architect in the studio of Gio Ponti in Milan (1960-62). Richard England's Maltese works include designs of numerous hotels (Ramla Bay Hotel, Paradise Bay Hotel, 1964; Dolmen Hotel, 1966; Cavalieri Hotel, 1968; Salina Bay Hotel, 1970), tourist villages, apartment complexes, bank buildings (Central Bank of Malta, Valletta, 1993), and the University of Malta campus extension (1990-1995). Richard England has also de signed residential and office complexes in Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Sardinia, and Argentina. His work has won numerous interna tional prizes and merited his inclusion among the 585 leading international architects treated in Contemporary Architects (London, 1994) and in the anthology of the 581 outstanding world architects published in Japan in 1995. Richard England's architecture is characterized by sim plicity and a respect for the "vernacular" tradition of Malta. His hotels, "low-lying, terraced structures built of concrete and local stone" (Abel, Manikata Church 39), disturb the landscape as little as possible. Michael Spens stresses "England's regionalism," with its roots in Maltese culture and pre-history SCRIPTA MEDITERRANEA, 1997, Vol. 18, 87 88 Brian f. Dendle (Spens 286) . Chris Abel points out the sculptural aspect of Eng land's buildings, "more Greek than Roman in spirit," "an archi tecture of shadow to create an architecture of light" (Trans formations 10). -

Malta & Gozo Directions

DIRECTIONS Malta & Gozo Up-to-date DIRECTIONS Inspired IDEAS User-friendly MAPS A ROUGH GUIDES SERIES Malta & Gozo DIRECTIONS WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Victor Paul Borg NEW YORK • LONDON • DELHI www.roughguides.com 2 Tips for reading this e-book Your e-book Reader has many options for viewing and navigating through an e-book. Explore the dropdown menus and toolbar at the top and the status bar at the bottom of the display window to familiarize yourself with these. The following guidelines are provided to assist users who are not familiar with PDF files. For a complete user guide, see the Help menu of your Reader. • You can read the pages in this e-book one at a time, or as two pages facing each other, as in a regular book. To select how you’d like to view the pages, click on the View menu on the top panel and choose the Single Page, Continuous, Facing or Continuous – Facing option. • You can scroll through the pages or use the arrows at the top or bottom of the display window to turn pages. You can also type a page number into the status bar at the bottom and be taken directly there. Or else use the arrows or the PageUp and PageDown keys on your keyboard. • You can view thumbnail images of all the pages by clicking on the Thumbnail tab on the left. Clicking on the thumbnail of a particular page will take you there. • You can use the Zoom In and Zoom Out tools (magnifying glass) to magnify or reduce the print size: click on the tool, then enclose what you want to magnify or reduce in a rectangle. -

Download the 2018 Encatc Congress Proceedings

The European network on cultural management and policy 2018 Congress Proceedings Beyond EYCH2018. What is the cultural horizon? Opening up perspectives to face ongoing transformations 9th Annual ENCATC Education and Research Session September 28, 2018 Bucharest, Romania Beyond EYCH2018. What is the cultural horizon? Opening up perspectives to face ongoing transformations BOOK PROCEEDINGS The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. Beyond EYCH2018. What is the cultural horizon? Opening up perspectives to face ongoing transformations Editor ENCATC Edited by Tanja Johansson, Sibelius Academy, University of the Arts Helsinki (Finland) Scientific Committee Members: Patrick Boylan, City, University of London (United Kingdom) John Carman, Ironbridge International Institute for Cultural Heritage, University of Birmingham (United Kingdom) Mara Cerquetti, University of Macerata (Italy) Hsiao-Ling Chung, National Cheng Kung University (Taiwan) Carmen Croitoru, National Institute for Cultural Research and Training (Romania) Jean-Louis Fabiani, Central European University in Budapest (Hungary) Annukka Jyrämä, Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre, (Estonia) Visnja Kisic, University of Arts Belgrade (Serbia) Johan Kolsteeg, Groningen University (The Netherlands) Tuuli Lähdesmäki, University of Jyväskylä (Finland) Bernadette -

THE LANGUAGE QUESTION in MALTA - the CONSCIOUSNESS of a NATIONAL IDENTITY by OLIVER FRIGGIERI

THE LANGUAGE QUESTION IN MALTA - THE CONSCIOUSNESS OF A NATIONAL IDENTITY by OLIVER FRIGGIERI The political and cultural history of Malta is largely determined by her having been a colony, a land seriously limited in her possibilities of acquiring self consciousness and of allowing her citizens to live in accordance with their own aspirations. Consequently the centuries of political submission may be equally defined as an uninterrupted experience of cultural submission. In the long run it has been a benevolent and fruitful submission. But culture, particularly art, is essentially a form of liberation. Lack of freedom in the way of life, therefore, resulted in lack of creativity. Nonetheless her very insularity was to help in the formation of an indigenous popular culture, segregated from the main foreign currents, but necessarily faithful to the conditions of the simple life of the people, a predominantly rural anrl nilioio115 life taken up by preoccupations of a subdued rather than rebellious nature, concerned with the family rather than with the nation. The development of the two traditional languages of Malta - the Italian language, cultured and written, and the Maltese, popular and spoken - can throw some light on this cultural and social dualism. The geographical position and the political history of the island brought about a very close link with Italy. In time the smallness of the island found its respectable place in the Mediterranean as European influence, mostly Italian, penetrated into the country and, owing to isolation, started to adopt little by little the local original aspects. The most significant factor of this phenomenon is that Malta created a literary culture (in its wider sense) written in Italian by the Maltese themselves. -

Livret Malte

A la conquê te de... Malte La Valette Carte d’identité Connais-tu le drapeau maltais ? • La superficie de Malte est de 316 km². 316 km² A C Saviez-vous • Le territoire maltais est un archipel situé au centre de la que...? mer Méditerranée, entre l’Afrique du Nord et le sud de l’Europe. B D • La capitale du pays est La Valette. Réponse : • Malte compte une population de 400 000 habitants, sa densité est la plus élevée de l’Union européenne. • L’hymne maltais a été créé en 1922. Ses paroles, à l’origine une prière dédiée à 400 000 la nation maltaise soulignant son attachement profond à cette terre, ont été habitants 2 écrites par Dun Karm Psaila, le plus célèbre des poètes maltais. La musique a été composée par Robert Samut. 3 • La monnaie du pays est l’euro, depuis janvier 2008. • Malte est une République parlementaire fortement inspirée du système hérité de la période coloniale britannique. • Malte a deux langues officielles, l’Anglais et le Maltais. Bongu ! • Du côté de l’exécutif, le président est élu pour cinq ans par la Chambre des représentants à la majorité absolue et il nomme le Premier ministre. S’agissant du pouvoir législatif, la Chambre des représentants est le Parlement unicaméral de • Deux spécialités culinaires maltes : Malte. Elle compte 65 députés élus pour cinq ans. Fenkata, lapin cuisiné en ragoût. L’histoire de ce plat ? On raconte qu’il ète la phrase ! s’agit d’une forme de résistance à l’époque des «Chevaliers de malte», ompl lorsqu’à leur arrivée ceux-ci imposèrent des restrictions concernant la C chasse au lapin.