French Protestantism, 1559-1562

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

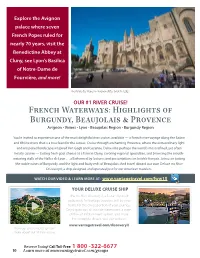

French Waterways: Highlights of Burgundy, Beaujolais & Provence

Explore the Avignon palace where seven French Popes ruled for nearly 70 years, visit the Benedictine Abbey at Cluny, see Lyon’s Basilica of Notre-Dame de Fourvière, and more! The Palais des Popes in Avignon dates back to 1252. OUR #1 RIVER CRUISE! French Waterways: Highlights of Burgundy, Beaujolais & Provence Avignon • Viviers • Lyon • Beaujolais Region • Burgundy Region You’re invited to experience one of the most delightful river cruises available — a French river voyage along the Saône and Rhône rivers that is a true feast for the senses. Cruise through enchanting Provence, where the extraordinary light and unspoiled landscapes inspired Van Gogh and Cezanne. Delve into perhaps the world’s most refined, yet often hearty cuisine — tasting fresh goat cheese at a farm in Cluny, savoring regional specialties, and browsing the mouth- watering stalls of the Halles de Lyon . all informed by lectures and presentations on la table français. Join us in tasting the noble wines of Burgundy, and the light and fruity reds of Beaujolais. And travel aboard our own Deluxe ms River Discovery II, a ship designed and operated just for our American travelers. WATCH OUR VIDEO & LEARN MORE AT: www.vantagetravel.com/fww15 Additional Online Content YOUR DELUXE CRUISE SHIP Facebook The ms River Discovery II, a 5-star ship built exclusively for Vantage travelers, will be your home for the cruise portion of your journey. Enjoy spacious, all outside staterooms, a state- of-the-art infotainment system, and more. For complete details, visit our website. www.vantagetravel.com/discoveryII View our online video to learn more about our #1 river cruise. -

Burgundy Beaujolais

The University of Kentucky Alumni Association Springtime in Provence Burgundy ◆ Beaujolais Cruising the Rhône and Saône Rivers aboard the Deluxe Small River Ship Amadeus Provence May 15 to 23, 2019 RESERVE BY SEPTEMBER 27, 2018 SAVE $2000 PER COUPLE Dear Alumni & Friends: We welcome all alumni, friends and family on this nine-day French sojourn. Visit Provence and the wine regions of Burgundy and Beaujolais en printemps (in springtime), a radiant time of year, when woodland hillsides are awash with the delicately mottled hues of an impressionist’s palette and the region’s famous flora is vibrant throughout the enchanting French countryside. Cruise for seven nights from Provençal Arles to historic Lyon along the fabled Rivers Rhône and Saône aboard the deluxe Amadeus Provence. During your intimate small ship cruise, dock in the heart of each port town and visit six UNESCO World Heritage sites, including the Roman city of Orange, the medieval papal palace of Avignon and the wonderfully preserved Roman amphitheater in Arles. Tour the legendary 15th- century Hôtel-Dieu in Beaune, famous for its intricate and colorful tiled roof, and picturesque Lyon, France’s gastronomique gateway. Enjoy an excursion to the Beaujolais vineyards for a private tour, world-class piano concert and wine tasting at the Château Montmelas, guided by the châtelaine, and visit the Burgundy region for an exclusive tour of Château de Rully, a medieval fortress that has belonged to the family of your guide, Count de Ternay, since the 12th century. A perennial favorite, this exclusive travel program is the quintessential Provençal experience and an excellent value featuring a comprehensive itinerary through the south of France in full bloom with springtime splendor. -

Metos, Merik the Vanishing Pope.Pdf

WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY THE VANISHING POPE MERIK HUNTER METOS SPRING 2009 ADVISOR: DR. SPOHNHOLZ DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS Honors Thesis ************************* PASS WITH DISTINCTION JOSI~~ s eLf" \\)J I \%\1 )10 dW JOJ JOS!Ape S!SalH· S\;/ :383110J S~ONOH A.1IS~31\INn 3H.1 0.1 PRECIS Pope Benoit XIII (1328-1423), although an influential advocate for reforms within the Catholic Church in the middle ages, receives little attention from modem historians. Historians rarely offer more than a brief biography and often neglect to mention at all his key role in the Great Schism. Yet, the very absence ofPope Benoit XIU from most historical narratives of medieval history itself highlights the active role that historians play in determining what gets recorded. In some cases, the choices that people make in determining what does, and what does not, get included in historical accounts reveals as much about the motivations and intentions of the people recording that past as it does about their subjects. This essay studies one example of this problem, in this case Europeans during the Reformation era who self-consciously manipulated sources from medieval history to promote their own agendas. We can see this in the sixteenth-century translation ofa treatise written by the medieval theologian Nicholas de Clamanges (1363-1437. Clamanges was a university professor and served as Benoit XIII's secretary during the Great Schism in Avignon, France. The treatise, entitled La Traite de fa Ruine de f'Eglise, was written in Latin in 1398 and was first distributed after Clamanges' death in 1437. -

Eurostar, the High-Speed Passenger Rail Service from the United Kingdom to Lille, Paris, Brussels And, Today, Uniquely, to Cannes

YOU R JOU RN EY LONDON TO CANNES . THE DAVINCI ONLYCODEIN cinemas . LONDON WATERLOO INTERNATIONAL Welcome to Eurostar, the high-speed passenger rail service from the United Kingdom to Lille, Paris, Brussels and, today, uniquely, to Cannes . Eurostar first began services in 1994 and has since become the air/rail market leader on the London-Paris and London-Brussels routes, offering a fast and seamless travel experience. A Eurostar train is around a quarter of a mile long, and carries up to 750 passengers, the equivalent of twojumbojets. 09 :40 Departure from London Waterloo station. The first part of ourjourney runs through South-East London following the classic domestic line out of the capital. 10:00 KENT REGION Kent is the region running from South-East London to the white cliffs of Dover on the south-eastern coast, where the Channel Tunnel begins. The beautiful rolling countryside and fertile lands of the region have been the backdrop for many historical moments. It was here in 55BC that Julius Caesar landed and uttered the famous words "Veni, vidi, vici" (1 came, l saw, 1 conquered). King Henry VIII first met wife number one, Anne of Cleaves, here, and his chieffruiterer planted the first apple and cherry trees, giving Kent the title of the 'Garden ofEngland'. Kent has also served as the setting for many films such as A Room with a View, The Secret Garden, Young Sherlock Holmes and Hamlet. 10:09 Fawkham Junction . This is the moment we change over to the high-speed line. From now on Eurostar can travel at a top speed of 186mph (300km/h). -

Royal Government in Guyenne During the First War of Religion

ROYAL GOVERNMENT IN GUYENNE DURING THE FIRST WAR OF RELIGION: 1561 - 1563 by DANIEL RICHARD BIRCH B.R.E., Northwest Baptist Theological College, i960 B.A., University of British Columbia, 1963 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA March, 1968 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his represen• tatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of History The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date March 21, 1968 - ABSTRACT - The purpose of this thesis was to investigate the principal challenges to royal authority and the means by which royal authority was maintained in France during the first War of Religion (1561-1563). The latter half of the sixteenth century was a critical period for the French monarchy. Great noble families attempted to re-establish their feudal power at the expense of the crown. Francis II and Charles IX, kings who were merely boys, succeeded strong monarchs on the throne. The kingdom was im• poverished by foreign wars and overrun by veteran soldiers, ill- absorbed into civil life. -

Catherine De' Medici: the Crafting of an Evil Legend

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2020 Apr 27th, 9:00 AM - 10:00 AM Catherine de' Medici: The Crafting of an Evil Legend Lindsey J. Donohue Clackamas High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, History Commons, and the Italian Language and Literature Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Donohue, Lindsey J., "Catherine de' Medici: The Crafting of an Evil Legend" (2020). Young Historians Conference. 23. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2020/papers/23 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. CATHERINE DE’ MEDICI: THE CRAFTING OF AN EVIL LEGEND Lindsey Donohue Western Civilization February 18, 2020 1 When describing the legend of the evil Italian queen, Catherine de’ Medici, and why Medici has been historically misrepresented, being credited with such malediction and wickedness, N.M Sutherland states that she has been viewed as a, “. .monster of selfish ambition, who sacrificed her children, her adopted country, her principles - if she ever had any - , and all who stood in her way to the satisfaction of her all-consuming desire for power.”1 The legend of the wicked Italian queen held widespread attraction among many, especially after Medici’s death in 1589. The famous legend paints Medici inaccurately by disregarding her achievements as queen regent as well as her constant struggle to administer peace during a time of intense political turmoil and religious feuding, and it assumes that Medici was a victim of circumstance. -

Von Greyerz Translated by Thomas Dunlap

Religion and Culture in Early Modern Europe, 1500–1800 This page intentionally left blank Religion and Culture in Early Modern Europe, 1500–1800 kaspar von greyerz translated by thomas dunlap 1 2008 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright # 2008 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Greyerz, Kaspar von. [Religion und Kultur. English] Religion and culture in early modern Europe, 1500–1800 / Kaspar von Greyerz ; Translated by Thomas Dunlap. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN: 978-0-19-532765-6 (cloth); 978-0-19-532766-3 (pbk.) 1. Religion and culture—Europe—History. 2. Europe—Religious life and customs. I. Title. BL65.C8G7413 2007 274'.06—dc22 2007001259 987654321 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper To Maya Widmer This page intentionally left blank Preface When I wrote the foreword to the original German edition of this book in March 2000, I took the secularized social and cultural cli- mate in which Europeans live today as a reason for reminding the reader of the special effort he or she had to make in order to grasp the central role of religion in the cultures and societies of early modern Europe. -

Introduction

Introduction The Other Voice [Monsieur de Voysenon] told [the soldiers] that in the past he had known me to be a good Catholic, but that he could not say whether or not I had remained that way. At that mo- ment arrived an honorable woman who asked them what they wanted to do with me; they told her, “By God, she is a Huguenot who ought to be drowned.” Charlotte Arbaleste Duplessis-Mornay, Memoirs The judge was talking about the people who had been ar- rested and the sorts of disguises they had used. All of this terrified me. But my fear was far greater when both the priest and the judge turned to me and said, “Here is a little rascal who could easily be a Huguenot.” I was very upset to see myself addressed that way. However, I responded with as much firmness as I could, “I can assure you, sir, that I am as much a Catholic as I am a boy.” Anne Marguerite Petit Du Noyer, Memoirs The cover of this book depicting Protestantism as a woman attacked on all sides reproduces the engraving that appears on the frontispiece of the first volume of Élie Benoist’s History of the Edict of Nantes.1 This illustration serves well Benoist’s purpose in writing his massive work, which was to protest both the injustice of revoking an “irrevocable” edict and the oppressive measures accompanying it. It also says much about the Huguenot experience in general, and the experience of Huguenot women in particular. When Benoist undertook the writing of his work, the association between Protestantism and women was not new. -

Cp 2018-374 Conseil Régional D’Île-De-France 2 Rapport N° Cp 2018-374

Rapport pour la commission permanente du conseil régional SEPTEMBRE 2018 Présenté par Valérie PÉCRESSE Présidente du conseil régional d’Île-de-France ATTRIBUTION DE SUBVENTIONS DANS LE CADRE DU DISPOSITIF DES CLUBS D'EXCELLENCE D'ÎLE-DE-FRANCE CP 2018-374 CONSEIL RÉGIONAL D’ÎLE-DE-FRANCE 2 RAPPORT N° CP 2018-374 Sommaire EXPOSÉ DES MOTIFS........................................................................................................................3 PROJET DE DÉLIBÉRATION..............................................................................................................4 ANNEXES À LA DÉLIBÉRATION........................................................................................................7 Annexe 1 Fiches projets Clubs d'excellence...................................................................................8 Annexe 2 Convention Jeanne d'Arc de Drancy..........................................................................117 06/09/2018 11:22:53 CONSEIL RÉGIONAL D’ÎLE-DE-FRANCE 3 RAPPORT N° CP 2018-374 EXPOSÉ DES MOTIFS L’article L1111-4 du Code général des collectivités territoriales (CGCT) reconnaît une compétence partagée entre les différents échelons de collectivités territoriales notamment dans les domaines de la culture, du sport, du tourisme. Par conséquent, ce rapport présente donc une affectation globale de 570 000 € d’autorisations d’engagement prélevées sur le chapitre 933 « Culture, Sports et Loisirs », code fonctionnel 32 « Sports » du budget 2018. Il propose d’attribuer 39 subventions pour -

The Lives of the Saints

'"Ill lljl ill! i j IIKI'IIIII '".'\;\\\ ','".. I i! li! millis i '"'''lllllllllllll II Hill P II j ill liiilH. CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Cornell University Library BR 1710.B25 1898 v.7 Lives of the saints. 3 1924 026 082 598 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924026082598 *— * THE 3Utoe* of tt)e Saints; REV. S. BARING-GOULD SIXTEEN VOLUMES VOLUME THE SEVENTH *- -* . l£ . : |£ THE Itoes of tfje faints BY THE REV. S. BARING-GOULD, M.A. New Edition in 16 Volumes Revised with Introduction and Additional Lives of English Martyrs, Cornish and Welsh Saints, and a full Index to the Entire Work ILLUSTRATED BY OVER 400 ENGRAVINGS VOLUME THE SEVENTH KttljJ— PARTI LONDON JOHN C. NIMMO &° ' 1 NEW YORK : LONGMANS, GREEN, CO. MDCCCXCVIII *• — ;— * Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co. At the Eallantyne Press *- -* CONTENTS' PAGE S. Athanasius, Deac. 127 SS. Aaron and Julius . I SS. AudaxandAnatholia 203 S. Adeodatus . .357 „ Agilulf . 211 SS. Alexanderandcomp. 207 S. Amalberga . , . 262 S. Bertha . 107 SS. AnatholiaandAudax 203 ,, Bonaventura 327 S. Anatolius,B. of Con- stantinople . 95 „ Anatolius, B.ofLao- dicea . 92 „ Andrew of Crete 106 S. Canute 264 Carileff. 12 „ Andrew of Rinn . 302 „ ... SS. Antiochus and SS. Castus and Secun- dinus Cyriac . 351 .... 3 Nicostra- S. Apollonius . 165 „ Claudius, SS. Apostles, The Sepa- tus, and others . 167 comp. ration of the . 347 „ Copres and 207 S. Cyndeus . 277 S. Apronia . .357 SS. Aquila and Pris- „ Cyril 205 Cyrus of Carthage . -

The Idea of Medieval Heresy in Early Modern France

The Idea of Medieval Heresy in Early Modern France Bethany Hume PhD University of York History September 2019 2 Abstract This thesis responds to the historiographical focus on the trope of the Albigensians and Waldensians within sixteenth-century confessional polemic. It supports a shift away from the consideration of medieval heresy in early modern historical writing merely as literary topoi of the French Wars of Religion. Instead, it argues for a more detailed examination of the medieval heretical and inquisitorial sources used within seventeenth-century French intellectual culture and religious polemic. It does this by examining the context of the Doat Commission (1663-1670), which transcribed a collection of inquisition registers from Languedoc, 1235-44. Jean de Doat (c.1600-1683), President of the Chambre des Comptes of the parlement of Pau from 1646, was charged by royal commission to the south of France to copy documents of interest to the Crown. This thesis aims to explore the Doat Commission within the wider context of ideas on medieval heresy in seventeenth-century France. The periodization “medieval” is extremely broad and incorporates many forms of heresy throughout Europe. As such, the scope of this thesis surveys how thirteenth-century heretics, namely the Albigensians and Waldensians, were portrayed in historical narrative in the 1600s. The field of study that this thesis hopes to contribute to includes the growth of historical interest in medieval heresy and its repression, and the search for original sources by seventeenth-century savants. By exploring the ideas of medieval heresy espoused by different intellectual networks it becomes clear that early modern European thought on medieval heresy informed antiquarianism, historical writing, and ideas of justice and persecution, as well as shaping confessional identity. -

The Dutch Poet Elisabeth Hoofman and Her German Patrons

Chapter 6 Possibilities of Patronage: The Dutch Poet Elisabeth Hoofman and Her German Patrons Nina Geerdink Patronage was a common practice for many early modern authors, but it was a public activity involving engagement with politics, pol- iticians and the rich and famous, and we know of relatively few women writers who profited from the benefits of patronage. The system of patronage altered, however, during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and one particular case study brings to light some of the possibilities and difficulties of this system for women writers. Elisabeth Hoofman (1664– 1736) was a Dutch poet whose authorship was representative of that of many writing women around 1700: born in a rich family, she wrote poetry in order to establish and consolidate contacts in a wealthy circle of friends and family, refusing to publish any of her poems. Her authorship status seems to have changed, though, after she and her husband lost their fortune and turned to rich patrons to secure their living. The circle of people addressed in her poetry broadened to power- ful men from outside of her intimate network and she started to print- publish. In this chapter, Hoofman’s opportunities to contrib- ute to the family income as a woman writer along with her abili- ty and necessity to manage her reputation are analysed with and through her poetry. ∵ Traditionally, Renaissance literary patronage has been regarded as a relation- ship between authors and patrons within the context of court culture. Pa- tronised authors received pensions for their poetic work, which they could produce relatively autonomously, as long as their literary reputation reflect- ed on the court and its ruler(s), and as long as their literary products could on occasion be used to amuse these ruler(s) and their guests.