Kant on Empiricism and Rationalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marxist Philosophy and the Problem of Value

Soviet Studies in Philosophy ISSN: 0038-5883 (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/mrsp19 Marxist Philosophy and the Problem of Value O. G. Drobnitskii To cite this article: O. G. Drobnitskii (1967) Marxist Philosophy and the Problem of Value, Soviet Studies in Philosophy, 5:4, 14-24 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.2753/RSP1061-1967050414 Published online: 20 Dec 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=mrsp19 Download by: [North Carolina State University], [Professor Marina Bykova] Date: 09 February 2017, At: 14:43 Theory of Value Voprosy filosofii, 1966, No. 7 0, G. Drobnitskii MARXIST PHILOSOPHY AND THE PROBLEM OF -*’VXLUr;* * In recent years, the question has been posed fact that things and phenomena in the world con- of the attitude of Marxist philosophy to what is stituting man’s environment have been endowed termed the problem of value. The point is not with such characteristics as worth, good and only that bourgeois axiology, which has been de- evil, beauty and ugliness, justice and injustice. veloping for three-quarters of a century, has to Doubtless, the phenomena of social consciousness be critically analyzed. Central to the question act in some aspect as “spiritual values,” i.e., is whether a Marxist axiology is possible. In they partake of the character of valuation norms. that connection the following is instructive. Finally, all these phenomena may be combined Authors who, with envious consistency, ignore under the single common notion of value. -

Life with Augustine

Life with Augustine ...a course in his spirit and guidance for daily living By Edmond A. Maher ii Life with Augustine © 2002 Augustinian Press Australia Sydney, Australia. Acknowledgements: The author wishes to acknowledge and thank the following people: ► the Augustinian Province of Our Mother of Good Counsel, Australia, for support- ing this project, with special mention of Pat Fahey osa, Kevin Burman osa, Pat Codd osa and Peter Jones osa ► Laurence Mooney osa for assistance in editing ► Michael Morahan osa for formatting this 2nd Edition ► John Coles, Peter Gagan, Dr. Frank McGrath fms (Brisbane CEO), Benet Fonck ofm, Peter Keogh sfo for sharing their vast experience in adult education ► John Rotelle osa, for granting us permission to use his English translation of Tarcisius van Bavel’s work Augustine (full bibliography within) and for his scholarly advice Megan Atkins for her formatting suggestions in the 1st Edition, that have carried over into this the 2nd ► those generous people who have completed the 1st Edition and suggested valuable improvements, especially Kath Neehouse and friends at Villanova College, Brisbane Foreword 1 Dear Participant Saint Augustine of Hippo is a figure in our history who has appealed to the curiosity and imagination of many generations. He is well known for being both sinner and saint, for being a bishop yet also a fellow pilgrim on the journey to God. One of the most popular and attractive persons across many centuries, his influence on the church has continued to our current day. He is also renowned for his influ- ence in philosophy and psychology and even (in an indirect way) art, music and architecture. -

Oppositions and Paradoxes in Mathematics and Philosophy

OPPOSITIONS AND PARADOXES IN MATHEMATICS AND PHILOSOPHY John L. Bell Abstract. In this paper a number of oppositions which have haunted mathematics and philosophy are described and analyzed. These include the Continuous and the Discrete, the One and the Many, the Finite and the Infinite, the Whole and the Part, and the Constant and the Variable. Underlying the evolution of mathematics and philosophy has been the attempt to reconcile a number of interlocking oppositions, oppositions which have on occasion crystallized into paradox and which continue to haunt mathematics to this day. These include the Continuous and the Discrete, the One and the Many, the Finite and the Infinite, the Whole and the Part, and the Constant and the Variable. Let me begin with the first of these oppositions—that between continuity and discreteness. Continuous entities possess the property of being indefinitely divisible without alteration of their essential nature. So, for instance, the water in a bucket may be continually halved and yet remain wateri. Discrete entities, on the other hand, typically cannot be divided without effecting a change in their nature: half a wheel is plainly no longer a wheel. Thus we have two contrasting properties: on the one hand, the property of being indivisible, separate or discrete, and, on the other, the property of being indefinitely divisible and continuous although not actually divided into parts. 2 Now one and the same object can, in a sense, possess both of these properties. For example, if the wheel is regarded simply as a piece of matter, it remains so on being divided in half. -

Russell's Paradox in Appendix B of the Principles of Mathematics

HISTORY AND PHILOSOPHY OF LOGIC, 22 (2001), 13± 28 Russell’s Paradox in Appendix B of the Principles of Mathematics: Was Frege’s response adequate? Ke v i n C. Kl e m e n t Department of Philosophy, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA 01003, USA Received March 2000 In their correspondence in 1902 and 1903, after discussing the Russell paradox, Russell and Frege discussed the paradox of propositions considered informally in Appendix B of Russell’s Principles of Mathematics. It seems that the proposition, p, stating the logical product of the class w, namely, the class of all propositions stating the logical product of a class they are not in, is in w if and only if it is not. Frege believed that this paradox was avoided within his philosophy due to his distinction between sense (Sinn) and reference (Bedeutung). However, I show that while the paradox as Russell formulates it is ill-formed with Frege’s extant logical system, if Frege’s system is expanded to contain the commitments of his philosophy of language, an analogue of this paradox is formulable. This and other concerns in Fregean intensional logic are discussed, and it is discovered that Frege’s logical system, even without its naive class theory embodied in its infamous Basic Law V, leads to inconsistencies when the theory of sense and reference is axiomatized therein. 1. Introduction Russell’s letter to Frege from June of 1902 in which he related his discovery of the Russell paradox was a monumental event in the history of logic. However, in the ensuing correspondence between Russell and Frege, the Russell paradox was not the only antinomy discussed. -

Praying and Contemplating in Late Antiquity Religious and Philosophical Interactions

Studien und Texte zu Antike und Christentum Studies and Texts in Antiquity and Christianity Herausgegeber / Editors Christoph Markschies (Berlin) · Martin Wallraff (München) Christian Wildberg (Princeton) Beirat / Advisory Board Peter Brown (Princeton) · Susanna Elm (Berkeley) Johannes Hahn (Münster) · Emanuela Prinzivalli (Rom) Jörg Rüpke (Erfurt) 113 Praying and Contemplating in Late Antiquity Religious and Philosophical Interactions Edited by Eleni Pachoumi and Mark Edwards Mohr Siebeck Eleni Pachoumi studied Classical Studies; 2007 PhD; worked as a Lecturer of Classical Philology at the University of Thessaly, the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and the University of Patras; Research Fellow at North-West University; currently Lecturer at the Open University in Greece and Academic Visiting Fellow in the Faculty of Classics, University of Oxford. Mark Edwards, 1984 BA in Literae Humaniores; 1990 BA in Theology; 1988 D. phil.; 1989 – 93 Junior Fellowship at New College; Tutor in Theology at Christ Church, Oxford and University Lecturer in Patristics in the Faculty of Theology, University of Oxford; since 2014 Professor of Early Christian Studies. ISBN 978-3-16-156119-1 / eISBN 978-3-16-156594-6 DOI 10.1628 / 978-3-16-156594-6 ISSN 1436-3003 / eISSN 2568-7433 (Studien und Texte zu Antike und Christentum) The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbiblio- graphie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Mohr Siebeck Tübingen. www.mohrsiebeck.com This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that per- mitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies partic- ularly to reproductions, translations and storage and processing in electronic systems. -

A Rationalist Argument for Libertarian Free Will

A rationalist argument for libertarian free will Stylianos Panagiotou PhD University of York Philosophy August 2020 Abstract In this thesis, I give an a priori argument in defense of libertarian free will. I conclude that given certain presuppositions, the ability to do otherwise is a necessary requirement for substantive rationality; the ability to think and act in light of reasons. ‘Transcendental’ arguments to the effect that determinism is inconsistent with rationality are predominantly forwarded in a Kantian manner. Their incorporation into the framework of critical philosophy renders the ontological status of their claims problematic; rather than being claims about how the world really is, they end up being claims about how the mind must conceive of it. To make their ontological status more secure, I provide a rationalist framework that turns them from claims about how the mind must view the world into claims about the ontology of rational agents. In the first chapter, I make some preliminary remarks about reason, reasons and rationality and argue that an agent’s access to alternative possibilities is a necessary condition for being under the scope of normative reasons. In the second chapter, I motivate rationalism about a priori justification. In the third chapter, I present the rationalist argument for libertarian free will and defend it against objections. Several objections rest on a compatibilist understanding of an agent’s abilities. To undercut them, I devote the fourth chapter, in which I give a new argument for incompatibilism between free will and determinism, which I call the situatedness argument for incompatibilism. If the presuppositions of the thesis are granted and the situatedness argument works, then we may be justified in thinking that to the extent that we are substantively rational, we are free in the libertarian sense. -

Definition and Construction Preprint 28.09

MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science 2006 PREPRINT 317 Gideon Freudenthal Definition and Construction Salomon Maimon’s Philosophy of Geometry Definition and Construction Salomon Maimon's Philosophy of Geometry Gideon Freudenthal 1. Introduction .........................................................................................................3 1.1. A Failed Proof and a Philosophical Conversion .................................................8 1.2. The Value of Mathematics ..................................................................................13 2. The Straight Line.................................................................................................15 2.1. Synthetic Judgments a priori Kantian and Aristotelean Style.............................15 2.2. Maimon's Proof that the Straight Line is also the shortest between Two Points ............................................................................................23 2.3. Kant's Critique and Maimon's Answer................................................................30 2.4. Definition, Construction, Proof in Euclid and Kant............................................33 2.5. The Construction of the Straight Line.................................................................37 2.6. The Turn to Empircial Skepticism (and Rational Dogmatism)...........................39 2.7. Synthetic a priori and proprium ..........................................................................46 2.8. Maimon's -

A KANTIAN REPLY to BOLZANO's CRITIQUE of KANT's ANALYTIC-SYNTHETIC DISTINCTION Nicholas F. STANG University of Miami Introdu

Grazer Philosophische Studien 85 (2012), 33–61. A KANTIAN REPLY TO BOLZANO’S CRITIQUE OF KANT’S ANALYTIC-SYNTHETIC DISTINCTION Nicholas F. STANG University of Miami Summary One of Bolzano’s objections to Kant’s way of drawing the analytic-synthetic distinction is that it only applies to judgments within a narrow range of syn- tactic forms, namely, universal affi rmative judgments. According to Bolzano, Kant cannot account for judgments of other syntactic forms that, intuitively, are analytic. A recent paper by Ian Proops also attributes to Kant the view that analytic judgments beyond a limited range of syntactic forms are impossible. I argue that, correctly understood, Kant’s conception of analyticity allows for analytic judgments of a wider range of syntactic forms. Introduction Although he praised Kant’s (re)discovery of the analytic-synthetic distinc- tion as having great signifi cance in the history of philosophy,1 Bolzano was sharply critical of how Kant drew that distinction. His criticisms include: (1) Th e distinction, as drawn by Kant, is unclear. (NAK, 34) 1. In Neuer Anti-Kant Příhonský writes: “Wir bemerken, daß, obgleich wir die Eintheilung der Urtheile in analytische und synthetische für eine der glücklichsten und einfl ußreichsten Entdeckungen halten, die je auf dem Gebiete der philosophischen Forschung sind gemacht worden, es uns doch scheinen wolle, als wenn sie von Kant nicht mit dem nöthigen Grade von Deutlichkeit aufgefaßt worden sei” (NAK, 34; cf. NAK, xxii). I say rediscovery because Bolzano recognizes that the distinction is inchoately present in Aristotle and Locke, and is made by Crusius in much the same way as Kant (WL, 87). -

Hegel's Concept of Recognition As the Solution to Kant's Third Antinomy

Chapter 12 Hegel’s Concept of Recognition as the Solution to Kant’s Third Antinomy Arthur Kok 1 Introduction In his Lectures on the history of philosophy, when discussing Kant’s third antin- omy, Hegel reproaches Kant for having “too much tenderness for the things”.1 In this contribution, I endeavor to explain what Hegel means by this criticism, and why it makes sense. Hegel values very much about Kant’s doctrine of the antinomies that it exposes the fundamental contradictions of reason. He calls this “the interest- ing side” of the antinomies.2 What is ‘interesting’ about them is that we cannot conceive of the absolute (uncaused) spontaneous origin of things, i.e. tran- scendental freedom, right away. The thesis that every causal chain of events presupposes a cause that is itself not caused contains the contradiction that an absolute spontaneity cannot take place according to rules, and hence can- not be understood in terms of causality.3 The antithesis, which rejects absolute spontaneity, makes this explicit, but it results in contradiction too: it is undeni- able that every causal chain posits an uncaused origin. The complete problem of the third antinomy thus is that we are forced to accept the assumption of transcendental freedom, but by doing so we postulate a contradiction. Kant argues that his transcendental idealism can resolve this contradic- tion. We shall see that Hegel does not accept Kant’s solution. I argue, however, that Hegel’s refutation of transcendental idealism does not mean that he does not take seriously the distinction between appearances and the Thing-in-itself. -

An Investigation Into a Postmodern Feminist Reading of Averroës

Journal of Feminist Scholarship Volume 10 Issue 10 Spring 2016 Article 5 Spring 2016 Bodies and Contexts: An Investigation into a Postmodern Feminist Reading of Averroës Reed Taylor University of Arkansas at Little Rock Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jfs Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Women's History Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Taylor, Reed. 2018. "Bodies and Contexts: An Investigation into a Postmodern Feminist Reading of Averroës." Journal of Feminist Scholarship 10 (Spring): 48-60. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jfs/vol10/ iss10/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Feminist Scholarship by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Taylor: Bodies and Contexts Bodies and Contexts: An Investigation into a Postmodern Feminist Reading of Averroës Reed Taylor, University of Arkansas at Little Rock Abstract: In this article, I contribute to the wider discourse of theorizing feminism in predominantly Muslim societies by analyzing the role of women’s political agency within the writings of the twelfth-century Islamic philosopher Averroës (Ibn Rushd, 1126–1198). I critically analyze Catarina Belo’s (2009) liberal feminist approach to political agency in Averroës by adopting a postmodern reading of Averroës’s commentary on Plato’s Republic. A postmodern feminist reading of Averroes’s political thought emphasizes contingencies and contextualization rather than employing a literal reading of the historical works. -

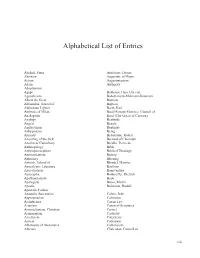

A-Z Entries List

Alphabetical List of Entries Abelard, Peter Attributes, Divine Abortion Augustine of Hippo Action Augustinianism Adam Authority Adoptionism Agape Balthasar, Hans Urs von Agnosticism Bañezianism-Molinism-Baianism Albert the Great Baptism Alexandria, School of Baptists Alphonsus Liguori Barth, Karl Ambrose of Milan Basel-Ferrara-Florence, Council of Anabaptists Basil (The Great) of Caesarea Analogy Beatitude Angels Beauty Anglicanism Beguines Anhypostasy Being Animals Bellarmine, Robert Anointing of the Sick Bernard of Clairvaux Anselm of Canterbury Bérulle, Pierre de Anthropology Bible Anthropomorphism Biblical Theology Antinomianism Bishop Antinomy Blessing Antioch, School of Blondel, Maurice Apocalyptic Literature Boethius Apocatastasis Bonaventure Apocrypha Bonhoeffer, Dietrich Apollinarianism Book Apologists Bucer, Martin Apostle Bultmann, Rudolf Apostolic Fathers Apostolic Succession Calvin, John Appropriation Calvinism Architecture Canon Law Arianism Canon of Scriptures Aristotelianism, Christian Carmel Arminianism Casuistry Asceticism Catechesis Aseitas Catharism Athanasius of Alexandria Catholicism Atheism Chalcedon, Council of xiii Alphabetical List of Entries Character Diphysitism Charisma Docetism Chartres, School of Doctor of the Church Childhood, Spiritual Dogma Choice Dogmatic Theology Christ/Christology Donatism Christ’s Consciousness Duns Scotus, John Chrysostom, John Church Ecclesiastical Discipline Church and State Ecclesiology Circumincession Ecology City Ecumenism Cleric Edwards, Jonathan Collegiality Enlightenment -

ABSTRACT Augustinian Auden: the Influence of Augustine of Hippo on W. H. Auden Stephen J. Schuler, Ph.D. Mentor: Richard Rankin

ABSTRACT Augustinian Auden: The Influence of Augustine of Hippo on W. H. Auden Stephen J. Schuler, Ph.D. Mentor: Richard Rankin Russell, Ph.D. It is widely acknowledged that W. H. Auden became a Christian in about 1940, but relatively little critical attention has been paid to Auden‟s theology, much less to the particular theological sources of Auden‟s faith. Auden read widely in theology, and one of his earliest and most important theological influences on his poetry and prose is Saint Augustine of Hippo. This dissertation explains the Augustinian origin of several crucial but often misunderstood features of Auden‟s work. They are, briefly, the nature of evil as privation of good; the affirmation of all existence, and especially the physical world and the human body, as intrinsically good; the difficult aspiration to the fusion of eros and agape in the concept of Christian charity; and the status of poetry as subject to both aesthetic and moral criteria. Auden had already been attracted to similar ideas in Lawrence, Blake, Freud, and Marx, but those thinkers‟ common insistence on the importance of physical existence took on new significance with Auden‟s acceptance of the Incarnation as an historical reality. For both Auden and Augustine, the Incarnation was proof that the physical world is redeemable. Auden recognized that if neither the physical world nor the human body are intrinsically evil, then the physical desires of the body, such as eros, the self-interested survival instinct, cannot in themselves be intrinsically evil. The conflict between eros and agape, or altruistic love, is not a Manichean struggle of darkness against light, but a struggle for appropriate placement in a hierarchy of values, and Auden derived several ideas about Christian charity from Augustine.