Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life with Augustine

Life with Augustine ...a course in his spirit and guidance for daily living By Edmond A. Maher ii Life with Augustine © 2002 Augustinian Press Australia Sydney, Australia. Acknowledgements: The author wishes to acknowledge and thank the following people: ► the Augustinian Province of Our Mother of Good Counsel, Australia, for support- ing this project, with special mention of Pat Fahey osa, Kevin Burman osa, Pat Codd osa and Peter Jones osa ► Laurence Mooney osa for assistance in editing ► Michael Morahan osa for formatting this 2nd Edition ► John Coles, Peter Gagan, Dr. Frank McGrath fms (Brisbane CEO), Benet Fonck ofm, Peter Keogh sfo for sharing their vast experience in adult education ► John Rotelle osa, for granting us permission to use his English translation of Tarcisius van Bavel’s work Augustine (full bibliography within) and for his scholarly advice Megan Atkins for her formatting suggestions in the 1st Edition, that have carried over into this the 2nd ► those generous people who have completed the 1st Edition and suggested valuable improvements, especially Kath Neehouse and friends at Villanova College, Brisbane Foreword 1 Dear Participant Saint Augustine of Hippo is a figure in our history who has appealed to the curiosity and imagination of many generations. He is well known for being both sinner and saint, for being a bishop yet also a fellow pilgrim on the journey to God. One of the most popular and attractive persons across many centuries, his influence on the church has continued to our current day. He is also renowned for his influ- ence in philosophy and psychology and even (in an indirect way) art, music and architecture. -

Kant on Empiricism and Rationalism

HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY QUARTERLY Volume 30, Number 1, January 2013 KANT ON EMPIRICISM AND RATIONALISM Alberto Vanzo his paper aims to correct some widely held misconceptions concern- T ing Kant’s role in the formation of a widespread narrative of early modern philosophy.1 According to this narrative, which dominated the English-speaking world throughout the twentieth century,2 the early modern period was characterized by the development of two rival schools: René Descartes’s, Baruch Spinoza’s, and G. W. Leibniz’s rationalism; and John Locke’s, George Berkeley’s, and David Hume’s empiricism. Empiricists and rationalists disagreed on whether all concepts are de- rived from experience and whether humans can have any substantive a priori knowledge, a priori knowledge of the physical world, or a priori metaphysical knowledge.3 The early modern period came to a close, so the narrative claims, once Immanuel Kant, who was neither an empiri- cist nor a rationalist, combined the insights of both movements in his new Critical philosophy. In so doing, Kant inaugurated the new eras of German idealism and late modern philosophy. Since the publication of influential studies by Louis Loeb and David Fate Norton,4 the standard narrative of early modern philosophy has come increasingly under attack. Critics hold that histories of early modern philosophy based on the rationalism-empiricism distinction (RED) have three biases—three biases for which, as we shall see, Kant is often blamed. The Epistemological Bias. Since disputes regarding a priori knowledge belong to epistemology, the RED is usually regarded as an epistemologi- cal distinction.5 Accordingly, histories of early modern philosophy based on the RED tend to assume that the core of early modern philosophy lies in the conflict between the “competing and mutually exclusive epis- temologies” of “rationalism and empiricism.”6 They typically interpret most of the central doctrines, developments, and disputes of the period in the light of philosophers’ commitment to empiricist or rationalist epistemologies. -

Praying and Contemplating in Late Antiquity Religious and Philosophical Interactions

Studien und Texte zu Antike und Christentum Studies and Texts in Antiquity and Christianity Herausgegeber / Editors Christoph Markschies (Berlin) · Martin Wallraff (München) Christian Wildberg (Princeton) Beirat / Advisory Board Peter Brown (Princeton) · Susanna Elm (Berkeley) Johannes Hahn (Münster) · Emanuela Prinzivalli (Rom) Jörg Rüpke (Erfurt) 113 Praying and Contemplating in Late Antiquity Religious and Philosophical Interactions Edited by Eleni Pachoumi and Mark Edwards Mohr Siebeck Eleni Pachoumi studied Classical Studies; 2007 PhD; worked as a Lecturer of Classical Philology at the University of Thessaly, the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and the University of Patras; Research Fellow at North-West University; currently Lecturer at the Open University in Greece and Academic Visiting Fellow in the Faculty of Classics, University of Oxford. Mark Edwards, 1984 BA in Literae Humaniores; 1990 BA in Theology; 1988 D. phil.; 1989 – 93 Junior Fellowship at New College; Tutor in Theology at Christ Church, Oxford and University Lecturer in Patristics in the Faculty of Theology, University of Oxford; since 2014 Professor of Early Christian Studies. ISBN 978-3-16-156119-1 / eISBN 978-3-16-156594-6 DOI 10.1628 / 978-3-16-156594-6 ISSN 1436-3003 / eISSN 2568-7433 (Studien und Texte zu Antike und Christentum) The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbiblio- graphie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Mohr Siebeck Tübingen. www.mohrsiebeck.com This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that per- mitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies partic- ularly to reproductions, translations and storage and processing in electronic systems. -

A Rationalist Argument for Libertarian Free Will

A rationalist argument for libertarian free will Stylianos Panagiotou PhD University of York Philosophy August 2020 Abstract In this thesis, I give an a priori argument in defense of libertarian free will. I conclude that given certain presuppositions, the ability to do otherwise is a necessary requirement for substantive rationality; the ability to think and act in light of reasons. ‘Transcendental’ arguments to the effect that determinism is inconsistent with rationality are predominantly forwarded in a Kantian manner. Their incorporation into the framework of critical philosophy renders the ontological status of their claims problematic; rather than being claims about how the world really is, they end up being claims about how the mind must conceive of it. To make their ontological status more secure, I provide a rationalist framework that turns them from claims about how the mind must view the world into claims about the ontology of rational agents. In the first chapter, I make some preliminary remarks about reason, reasons and rationality and argue that an agent’s access to alternative possibilities is a necessary condition for being under the scope of normative reasons. In the second chapter, I motivate rationalism about a priori justification. In the third chapter, I present the rationalist argument for libertarian free will and defend it against objections. Several objections rest on a compatibilist understanding of an agent’s abilities. To undercut them, I devote the fourth chapter, in which I give a new argument for incompatibilism between free will and determinism, which I call the situatedness argument for incompatibilism. If the presuppositions of the thesis are granted and the situatedness argument works, then we may be justified in thinking that to the extent that we are substantively rational, we are free in the libertarian sense. -

An Investigation Into a Postmodern Feminist Reading of Averroës

Journal of Feminist Scholarship Volume 10 Issue 10 Spring 2016 Article 5 Spring 2016 Bodies and Contexts: An Investigation into a Postmodern Feminist Reading of Averroës Reed Taylor University of Arkansas at Little Rock Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jfs Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Women's History Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Taylor, Reed. 2018. "Bodies and Contexts: An Investigation into a Postmodern Feminist Reading of Averroës." Journal of Feminist Scholarship 10 (Spring): 48-60. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jfs/vol10/ iss10/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Feminist Scholarship by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Taylor: Bodies and Contexts Bodies and Contexts: An Investigation into a Postmodern Feminist Reading of Averroës Reed Taylor, University of Arkansas at Little Rock Abstract: In this article, I contribute to the wider discourse of theorizing feminism in predominantly Muslim societies by analyzing the role of women’s political agency within the writings of the twelfth-century Islamic philosopher Averroës (Ibn Rushd, 1126–1198). I critically analyze Catarina Belo’s (2009) liberal feminist approach to political agency in Averroës by adopting a postmodern reading of Averroës’s commentary on Plato’s Republic. A postmodern feminist reading of Averroes’s political thought emphasizes contingencies and contextualization rather than employing a literal reading of the historical works. -

A-Z Entries List

Alphabetical List of Entries Abelard, Peter Attributes, Divine Abortion Augustine of Hippo Action Augustinianism Adam Authority Adoptionism Agape Balthasar, Hans Urs von Agnosticism Bañezianism-Molinism-Baianism Albert the Great Baptism Alexandria, School of Baptists Alphonsus Liguori Barth, Karl Ambrose of Milan Basel-Ferrara-Florence, Council of Anabaptists Basil (The Great) of Caesarea Analogy Beatitude Angels Beauty Anglicanism Beguines Anhypostasy Being Animals Bellarmine, Robert Anointing of the Sick Bernard of Clairvaux Anselm of Canterbury Bérulle, Pierre de Anthropology Bible Anthropomorphism Biblical Theology Antinomianism Bishop Antinomy Blessing Antioch, School of Blondel, Maurice Apocalyptic Literature Boethius Apocatastasis Bonaventure Apocrypha Bonhoeffer, Dietrich Apollinarianism Book Apologists Bucer, Martin Apostle Bultmann, Rudolf Apostolic Fathers Apostolic Succession Calvin, John Appropriation Calvinism Architecture Canon Law Arianism Canon of Scriptures Aristotelianism, Christian Carmel Arminianism Casuistry Asceticism Catechesis Aseitas Catharism Athanasius of Alexandria Catholicism Atheism Chalcedon, Council of xiii Alphabetical List of Entries Character Diphysitism Charisma Docetism Chartres, School of Doctor of the Church Childhood, Spiritual Dogma Choice Dogmatic Theology Christ/Christology Donatism Christ’s Consciousness Duns Scotus, John Chrysostom, John Church Ecclesiastical Discipline Church and State Ecclesiology Circumincession Ecology City Ecumenism Cleric Edwards, Jonathan Collegiality Enlightenment -

ABSTRACT Augustinian Auden: the Influence of Augustine of Hippo on W. H. Auden Stephen J. Schuler, Ph.D. Mentor: Richard Rankin

ABSTRACT Augustinian Auden: The Influence of Augustine of Hippo on W. H. Auden Stephen J. Schuler, Ph.D. Mentor: Richard Rankin Russell, Ph.D. It is widely acknowledged that W. H. Auden became a Christian in about 1940, but relatively little critical attention has been paid to Auden‟s theology, much less to the particular theological sources of Auden‟s faith. Auden read widely in theology, and one of his earliest and most important theological influences on his poetry and prose is Saint Augustine of Hippo. This dissertation explains the Augustinian origin of several crucial but often misunderstood features of Auden‟s work. They are, briefly, the nature of evil as privation of good; the affirmation of all existence, and especially the physical world and the human body, as intrinsically good; the difficult aspiration to the fusion of eros and agape in the concept of Christian charity; and the status of poetry as subject to both aesthetic and moral criteria. Auden had already been attracted to similar ideas in Lawrence, Blake, Freud, and Marx, but those thinkers‟ common insistence on the importance of physical existence took on new significance with Auden‟s acceptance of the Incarnation as an historical reality. For both Auden and Augustine, the Incarnation was proof that the physical world is redeemable. Auden recognized that if neither the physical world nor the human body are intrinsically evil, then the physical desires of the body, such as eros, the self-interested survival instinct, cannot in themselves be intrinsically evil. The conflict between eros and agape, or altruistic love, is not a Manichean struggle of darkness against light, but a struggle for appropriate placement in a hierarchy of values, and Auden derived several ideas about Christian charity from Augustine. -

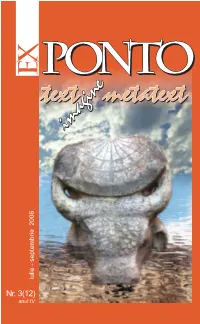

Nr. 3 (12), (Anul IV), Iulie - Septembrie, 2006 EX PONTO Text/Imagine/Metatext

2006 septembrie - iulie Nr. 3(12) anul IV EX PONTO TEXT/IMAGINE/METATEXT Nr. 3 (12), (Anul IV), iulie - septembrie, 2006 EX PONTO text/imagine/metatext Revistă trimestrială publicată de Editura Ex Ponto şi S.C. InFCon S.A. Director: IoAn PoPIŞtEAnU Director general: PAUL PRoDAn Apare sub egida Uniunii Scriitorilor din România, cu susţinerea Filialei „Dobrogea“ a Uniunii Scriitorilor din România, Direcţiilor Judeţene pentru Cultură, Culte şi Patrimoniul Cul tural naţional Constanţa şi tulcea şi a Universităţii „ovidius“ Constanţa Redacţia: Redactor şef: OVIDIU DUNĂREANU Redactor şef adjunct: nICoLAE RotUnD Redactori: AngELo MItChIEvICI, ILEAnA MARIn (S.U.A.) Prezentare grafică: ConStAntIn gRIgoRUŢĂ tehnoredactare şi corectură: AURA DUMItRAChE Colegiul: SoRIn ALExAnDRESCU, Acad. SoLoMon MARCUS, ConStAntIn novAC, nICoLAE MOTOC, RADU CÎRnECI, vICTOR CIUPInĂ, Ion BITOLEAnU, STOICA LASCU, ADInA CIUgUREAnU, FLoREnŢA MARInESCU, AxEnIA hogEA, IoAn PoPIŞtEAnU, oLIMPIU vLADIMIRov Revista Ex Ponto găzduieşte opiniile, oricât de diverse, ale colaboratorilor. Responsabilitatea pentru conţinutul fiecărui text aparţine în exclusivitate autorului. Redacţia: Bd. Mamaia nr. 126, Constanţa, 900527; tel./fax: 0241 / 616880; email: library@bcu ovidius.ro Administraţia: Aleea Prof. Murgoci nr. 1, Constanţa, 900132; tel./fax: 0241 / 580527 / 585627 Revista se difuzează: – în Constanţa, prin reţeaua chioşcurilor „Cuget Liber” S.A. – în Bucureşti, prin Centrul de Difuzare a Presei de la Muzeul Literaturii Române – în străinătate, cu sprijinul „Departamentului românilor de pretutindeni” al Ministerului de Externe Revista Ex Ponto este membră a A.R.I.E.L. (Asociaţia Revistelor, Imprimeriilor şi Editurilor Literare) tiparul: S.C. Infcon S.A. Constanţa ISSn: 1584-1189 SUMAR ♦Editorial ♦Traduceri din literatura română ovIDIU DUnĂREAnU – Scriitorul şi soci- ILEAnA MĂLĂnCIoIU şi GHEoRGHE etatea (p. -

Periyar Periyar the Great Thinker the Great Thinker

PERIYAR PERIYAR THE GREAT THINKER THE GREAT THINKER Author : Pannan Translated by : Prof. B.S.Govindarajan Published by: PERIYAR PATTARAI 7/11 Alivalam Road Published by: Sundravilagam PERIYAR PATTARAI Thiruvarur 610 001 Chapter, ‘The Possession of Knowledge’. 1. THE ONLY GREAT MAN “Though things diverse from divers sages’ lips we learn, On hearing the word Philosper or Thinker, we normally mean a person Tis wisdom’s part in each the true thing to discern” who thought of God,the origin of the world and the species, one who has (To discern the truth in everything, by whomsoever spoken is wisdom) guided us to reach the feet of the Almighty, who has established the Thiruvalluvar also defines Philosphy in a couplet in the Chapter difference between the mortals and immortals, who has come to relieve “Knowing the Truth”. the people from their sufferings, who has explained the need for the present life in this world and showed us the right path to the next world, to live in “Whatever thing, of whatsoever kind it be, after death. Tis wisdom’s part in each the very thing to see.” It is because, all the thinkers in the East were engaged in giving (“(True) Knowledge is the perception concerning everything of whatever interpretations to the Philosophy of God which existed already among kind, that, that thing is the true thing”). people; preaching True God and False God and directing the people to From the above two statements, the difference between knowledge divert from the old to new path to get rid of this life. -

A Study of Plotinus' Ennead VI.8

Freedom and the Good: A Study of Plotinus’ Ennead VI.8 [39] by Aaron Higgins-Brake Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia August 2015 © Copyright by Aaron Higgins-Brake, 2015 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………….. iii List of Abbreviations Used………………………………………………………………… iv Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………… v Chapter 1: Introduction…………………………………………………………………….. 1 1.1 Experience and Reason……………………………………………………….... 1 1.2 Freedom and Rationality……………………………………………………….. 8 Chapter 2: Freedom, Responsibility, and the Place of the Human…………………....…… 11 2.1 Human Action in Plotinus and its Hellenistic Background…….…………….... 11 2.2 Freedom and Responsibility among the Stoics and Epicureans……………….. 13 2.2 Aristotle and Plotinus on Voluntary Action…………………………………….20 Chapter 3: The Freedom of the One……………………………………………………….. 31 3.1 Origins of the Problematic of Ennead VI.8 [39]..................................................31 3.2 Contingency and Necessity Redivivus…………………………………………. 39 Chapter 4: Procession and Return………………………………………………………….. 49 4.1 From the ‗Will of Itself‘ to the ‗Will of the All‘.................................................. 49 4.2 From Procession to Reversion…………………………………………………. 55 Chapter 5: Conclusion………………………………………………………………………63 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………...67 ii Abstract This thesis investigates Plotinus‘ Ennead VI.8 [39] with a view to reevaluating what scholars have frequently considered to be the problematic implications of his metaphysical thought, and, in particular, Plotinus‘ supposed irrationalism. Our investigation shows that Plotinus is careful to develop an account of freedom that is distinct from acting arbitrarily, without thereby being necessitated or compelled – a development that is already clear in his reflections on human action. Plotinus‘ account culminates in his novel reinterpretation of the first principle, the Good, as the will of itself. -

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, the Humanist Agenda and the Scientific Method

3237827: M.Sc. Dissertation Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, the humanist agenda and the scientific method Kundan Misra A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Research), University of New South Wales School of Mathematics and Statistics Faculty of Science University of New South Wales Submitted August 2011 Changes completed September 2012 THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Misra First name: Kundan Other name/s: n/a Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: MSc School: Mathematics and Statistics Faculty: Science Title: Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, the humanist agenda and the scientific method Abstract 350 words maximum: Modernity began in Leibniz’s lifetime, arguably, and due to the efforts of a group of philosopher-scientists of which Leibniz was one of the most significant active contributors. Leibniz invented machines and developed the calculus. He was a force for peace, and industrial and cultural development through his work as a diplomat and correspondence with leaders across Europe, and in Russia and China. With Leibniz, science became a means for improving human living conditions. For Leibniz, science must begin with the “God’s eye view” and begin with an understanding of how the Creator would have designed the universe. Accordingly, Leibniz advocated the a priori method of scientific discovery, including the use of intellectual constructions or artifices. He defended the usefulness and success of these methods against detractors. While cognizant of Baconian empiricism, Leibniz found that an unbalanced emphasis on experiment left the investigator short of conclusions on efficient causes. -

Al-Ghazali and Ibn Rushd (Averroes) on Creation and the Divine Attributes

Al-Ghazali and Ibn Rushd (Averroes) on Creation and the Divine Attributes Ali Hasan Early in the history of Islam, in the eighth and ninth Centuries, theologians discussed the nature and implications of the divine attributes, and did so with increasing sophistication as the growth of Islam led to a rapid absorption of Greek philosophy. Abu Hamid Muhammad ibn Muhammad al-Ghazali (1058–1111) and Abu al-Walid Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Rushd (“Averroes”, 1126–1198) continued the debate, developing models of God that they took to be compatible with the Qur’an and the spirit of Islam. Al-Ghazali and Ibn Rushd disagreed signi fi cantly, however, on God’s nature and His relation to the world, and on the appropriate way to proceed when philosophizing about God. Reason, Revelation, and Interpretation A Muslim who lacks knowledge on matters metaphysical, moral, or spiritual may feel that Islam provides more than enough guidance on its own. There is the Qur’an, God’s message to humanity, which is the primary source of guidance; the sunna or “tradition”, consisting of reports of the sayings ( ahadith ) and practices of the Prophet Mohammed; and the principles of Islamic law (Shari’a ) built upon these sources. However, the mention of these sources naturally invites questions about their reliability and interpretation. There is, of course, the question of why we should accept the Qur’an as God’s creation. As much as Muslims are unlikely to doubt that the Qur’an is God’s word, they are just as likely to claim that we have good reasons to believe that God exists and that the Qur’an is God’s message to humankind.