Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History and Theory of Philosophy

FEDERAL STATE BUDGETARY EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION OF HIGHER EDUCATION "BASHKIR STATE MEDICAL UNIVERSITY" OF THE MINISTRY OF HEALTHCARE OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION (FSBEI HE BSMU MOH Russia) HISTORY AND THEORY OF PHILOSOPHY Textbook Ufa 2020 1 UDC 1(09)(075.8) BBC 87.3я7 H90 Reviewers: Doctor of Philosophy, Professor, Head of the department «Social work» FSBEI HE «Bashkir State University» U.S. Vildanov Doctor of Philosophy, Professor at the Department of Philosophy and History FSBEIHE «Bashkir State Agricultural University» A.I. Stoletov History and theory of philosophy:textbook/ K.V. Khramova, H90 R.I. Devyatkina, Z.R. Sadikova, O.M. Ivanova, O.G. Afanasyeva, A.S. Zubairova-Valeeva, N.R. Mingazova, G.R. Davletshina — Ufa: Ufa: FSBEIHEBSMUMOHRussia, 2020. – 127 p. The manual was prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Federal State Educational Standard of Higher Education in specialty 31.05.01 «General Medicine» the current curriculum and on the basis of the work program on the discipline of philosophy. The manual is focused on the competence-based learning model. It has an original, uniform for all classes structure, including the topic, a summary of the training questions, the subject of essays, training materials, test items with response standards, recommended literature. This manual covers topics related to the periods of development of world philosophy. Designed for students in the specialty 31.05.01 «General Medicine». It is recommended to be published by the Coordinating Scientific and Methodological Council and was approved by the decision of the Editorial and Publishing Council of the BSMU of the Ministry of Healthcare of Russia. -

Life with Augustine

Life with Augustine ...a course in his spirit and guidance for daily living By Edmond A. Maher ii Life with Augustine © 2002 Augustinian Press Australia Sydney, Australia. Acknowledgements: The author wishes to acknowledge and thank the following people: ► the Augustinian Province of Our Mother of Good Counsel, Australia, for support- ing this project, with special mention of Pat Fahey osa, Kevin Burman osa, Pat Codd osa and Peter Jones osa ► Laurence Mooney osa for assistance in editing ► Michael Morahan osa for formatting this 2nd Edition ► John Coles, Peter Gagan, Dr. Frank McGrath fms (Brisbane CEO), Benet Fonck ofm, Peter Keogh sfo for sharing their vast experience in adult education ► John Rotelle osa, for granting us permission to use his English translation of Tarcisius van Bavel’s work Augustine (full bibliography within) and for his scholarly advice Megan Atkins for her formatting suggestions in the 1st Edition, that have carried over into this the 2nd ► those generous people who have completed the 1st Edition and suggested valuable improvements, especially Kath Neehouse and friends at Villanova College, Brisbane Foreword 1 Dear Participant Saint Augustine of Hippo is a figure in our history who has appealed to the curiosity and imagination of many generations. He is well known for being both sinner and saint, for being a bishop yet also a fellow pilgrim on the journey to God. One of the most popular and attractive persons across many centuries, his influence on the church has continued to our current day. He is also renowned for his influ- ence in philosophy and psychology and even (in an indirect way) art, music and architecture. -

Kant on Empiricism and Rationalism

HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY QUARTERLY Volume 30, Number 1, January 2013 KANT ON EMPIRICISM AND RATIONALISM Alberto Vanzo his paper aims to correct some widely held misconceptions concern- T ing Kant’s role in the formation of a widespread narrative of early modern philosophy.1 According to this narrative, which dominated the English-speaking world throughout the twentieth century,2 the early modern period was characterized by the development of two rival schools: René Descartes’s, Baruch Spinoza’s, and G. W. Leibniz’s rationalism; and John Locke’s, George Berkeley’s, and David Hume’s empiricism. Empiricists and rationalists disagreed on whether all concepts are de- rived from experience and whether humans can have any substantive a priori knowledge, a priori knowledge of the physical world, or a priori metaphysical knowledge.3 The early modern period came to a close, so the narrative claims, once Immanuel Kant, who was neither an empiri- cist nor a rationalist, combined the insights of both movements in his new Critical philosophy. In so doing, Kant inaugurated the new eras of German idealism and late modern philosophy. Since the publication of influential studies by Louis Loeb and David Fate Norton,4 the standard narrative of early modern philosophy has come increasingly under attack. Critics hold that histories of early modern philosophy based on the rationalism-empiricism distinction (RED) have three biases—three biases for which, as we shall see, Kant is often blamed. The Epistemological Bias. Since disputes regarding a priori knowledge belong to epistemology, the RED is usually regarded as an epistemologi- cal distinction.5 Accordingly, histories of early modern philosophy based on the RED tend to assume that the core of early modern philosophy lies in the conflict between the “competing and mutually exclusive epis- temologies” of “rationalism and empiricism.”6 They typically interpret most of the central doctrines, developments, and disputes of the period in the light of philosophers’ commitment to empiricist or rationalist epistemologies. -

Praying and Contemplating in Late Antiquity Religious and Philosophical Interactions

Studien und Texte zu Antike und Christentum Studies and Texts in Antiquity and Christianity Herausgegeber / Editors Christoph Markschies (Berlin) · Martin Wallraff (München) Christian Wildberg (Princeton) Beirat / Advisory Board Peter Brown (Princeton) · Susanna Elm (Berkeley) Johannes Hahn (Münster) · Emanuela Prinzivalli (Rom) Jörg Rüpke (Erfurt) 113 Praying and Contemplating in Late Antiquity Religious and Philosophical Interactions Edited by Eleni Pachoumi and Mark Edwards Mohr Siebeck Eleni Pachoumi studied Classical Studies; 2007 PhD; worked as a Lecturer of Classical Philology at the University of Thessaly, the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and the University of Patras; Research Fellow at North-West University; currently Lecturer at the Open University in Greece and Academic Visiting Fellow in the Faculty of Classics, University of Oxford. Mark Edwards, 1984 BA in Literae Humaniores; 1990 BA in Theology; 1988 D. phil.; 1989 – 93 Junior Fellowship at New College; Tutor in Theology at Christ Church, Oxford and University Lecturer in Patristics in the Faculty of Theology, University of Oxford; since 2014 Professor of Early Christian Studies. ISBN 978-3-16-156119-1 / eISBN 978-3-16-156594-6 DOI 10.1628 / 978-3-16-156594-6 ISSN 1436-3003 / eISSN 2568-7433 (Studien und Texte zu Antike und Christentum) The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbiblio- graphie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Mohr Siebeck Tübingen. www.mohrsiebeck.com This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that per- mitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies partic- ularly to reproductions, translations and storage and processing in electronic systems. -

The Outcome of Classical German Philosophy History 71600/CL

The Outcome of Classical German Philosophy History 71600/CL 85000/PSC Prof. Wolin (GC 5114) Fall 2019 [email protected] Mon. 6:30-8:30 Room: GC ?? In 1886, Friedrich Engels wrote a perfectly mediocre book, Ludwig Feuerbach and the Outcome of Classical German Philosophy, which nevertheless managed to raise a fascinating and important question that is still being debated today: how should we go about evaluating the legacy of German Idealism following the mid-nineteenth century breakdown of the Hegelian system? For Engels, the answer was relatively simple: the rightful heir of classical German philosophy was Marx’s doctrine of historical materialism. But, in truth, Engels’ response was merely one of many possible approaches. Nor would it be much of an exaggeration to claim that, in the twentieth century, there is hardly a philosopher worth reading who has not sought to define him or herself via a confrontation with the legacy of Kant and Hegel. Classical German Philosophy – Kant, Fichte, Hegel, and Schelling – has bequeathed a rich legacy of reflection on the fundamental problems of epistemology, ontology and aesthetics. Even contemporary thinkers who claim to have transcended it (e.g., poststructuralists such as Foucault and Derrida) cannot help but make reference to it in order to validate their post- philosophical standpoints and claims. Our approach to this very rich material will combine a reading of the canonical texts of German Idealism (e.g., Kant and Hegel) with a sustained and complementary focus on major twentieth-century thinkers who have sought to establish their originality via a critical reading of Hegel and his heirs: Alexandre Kojève, Martin Heidegger, Michel Foucault, Theodor Adorno, and Jürgen Habermas. -

210 the Genesis of Neo-Kantianism

SYNTHESIS PHILOSOPHICA Book Reviews / Buchbesprechungen 61 (1/2016) pp. (207–220) 210 doi: 10.21464/sp31116 of his book is that the movement’s origins are to be found already in the 1790s, in the Frederick Charles Beiser works of Jakob Friedrich Fries, Johann Frie- drich Herbart, and Friedrich Eduard Beneke. They constitute “the lost tradition” which pre- The Genesis of served the “empiricist-psychological” side of Neo-Kantianism Kant’s thought, his dualisms, and things-in- themselves against the excessive speculative idealism of Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel who Oxford University Press, tried to rehabilitate the dogmatic rationalist Oxford 2014 metaphysics of Spinoza, Leibniz, and Wolff after Kant’s critical project. Frederick Charles Beiser, professor of phi- The first chapter of the first part (pp. 23–88) losophy at Syracuse University (USA) whose is concerned with the philosophy of Fries field of expertise is the modern German phi- who tried to base philosophy on empirical losophy, is one of the most erudite historians psychology, and epistemology on psychol- of philosophy today. His first book The Fate ogy which could recognize the synthetic a of Reason: German Philosophy from Kant priori but not prove it. His book Reinhold, to Fichte (1987) didn’t only present a fresh Fichte und Schelling (1803) saw the history account of German philosophy at the end of of philosophy after Kant as the “struggle of th the 18 century, but it also introduced a new rationalism to free itself from the limits of method of historical research. His more re- the critique”. In his political philosophy Fries cent works, starting with The German His- was an anti-Semite, but gave the leading role toricist Tradition (2011) until the most recent to public opinion which could correct even Weltschmerz: Pessimism in German Philoso- the ruler, although he encountered problems phy, 1860–1900 (2016), have focused on the in trying to reconcile his liberal views with th main currents of the 19 century German the social injustice that liberalism created. -

Rachel Elizabeth Zuckert Department of Philosophy 5728 N. Kenmore

Rachel Elizabeth Zuckert Department of Philosophy 5728 N. Kenmore Ave, 3N Northwestern University Chicago, IL 60660 Kresge 3-512 1880 Campus Drive home: (773) 728-7927 Evanston, IL 60208 work: (847) 491-2556 [email protected] Education: 2000 PhD, University of Chicago, Department of Philosophy and the Committee on Social Thought 1995 MA, University of Chicago, Committee on Social Thought 1992 B.A. (1), Oxford University (Philosophy and Modern Languages) 1990 B.A. (Summa Cum Laude; Highest Honors in Philosophy; Phi Beta Kappa), Williams College Areas of Specialization: Kant and eighteenth-century philosophy Aesthetics Areas of Competence: Early modern philosophy Nineteenth-century philosophy Feminist philosophy Languages: French German Academic Employment: 2018- Professor of Philosophy, Northwestern University; affiliated with the German Department 2008-18 Associate Professor of Philosophy, Northwestern University; affiliated with the German Department 2011-18 2006-2008 Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Northwestern University 2001-2006 Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Rice University 1999-2001 Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Bucknell University Zuckert 2 Publications: Books Kant on Beauty and Biology: An Interpretation of the Critique of Judgment, Cambridge University Press, 2007. Awarded the American Society for Aesthetics Monograph Prize (2008); reviewed in British Journal for the History of Philosophy, Comparative and Continental Philosophy, Graduate Faculty Philosophy Journal, Journal of the History of Philosophy, Metascience, Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews, Review of Metaphysics, and subject of review essays in Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism and Kant Yearbook Herder’s Naturalist Aesthetics, Cambridge University Press, forthcoming (2019). Edited Volume Hegel on Philosophy in History, co-edited with James Kreines, Cambridge University Press, 2017. -

A Rationalist Argument for Libertarian Free Will

A rationalist argument for libertarian free will Stylianos Panagiotou PhD University of York Philosophy August 2020 Abstract In this thesis, I give an a priori argument in defense of libertarian free will. I conclude that given certain presuppositions, the ability to do otherwise is a necessary requirement for substantive rationality; the ability to think and act in light of reasons. ‘Transcendental’ arguments to the effect that determinism is inconsistent with rationality are predominantly forwarded in a Kantian manner. Their incorporation into the framework of critical philosophy renders the ontological status of their claims problematic; rather than being claims about how the world really is, they end up being claims about how the mind must conceive of it. To make their ontological status more secure, I provide a rationalist framework that turns them from claims about how the mind must view the world into claims about the ontology of rational agents. In the first chapter, I make some preliminary remarks about reason, reasons and rationality and argue that an agent’s access to alternative possibilities is a necessary condition for being under the scope of normative reasons. In the second chapter, I motivate rationalism about a priori justification. In the third chapter, I present the rationalist argument for libertarian free will and defend it against objections. Several objections rest on a compatibilist understanding of an agent’s abilities. To undercut them, I devote the fourth chapter, in which I give a new argument for incompatibilism between free will and determinism, which I call the situatedness argument for incompatibilism. If the presuppositions of the thesis are granted and the situatedness argument works, then we may be justified in thinking that to the extent that we are substantively rational, we are free in the libertarian sense. -

Immanuel Kant and the Development of Modern Psychology David E

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Psychology Faculty Publications Psychology 1982 Immanuel Kant and the Development of Modern Psychology David E. Leary University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/psychology-faculty- publications Part of the Theory and Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Leary, David E. "Immanuel Kant and the Development of Modern Psychology." In The Problematic Science: Psychology in Nineteenth- Century Thought, edited by William Ray Woodward and Mitchell G. Ash, 17-42. New York, NY: Praeger, 1982. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Psychology at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Psychology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Immanuel Kant and the Development of Modern Psychology David E. Leary Few thinkers in the history of Western civilization have had as broad and lasting an impact as Immanuel Kant (1724-1804). This "Sage of Konigsberg" spent his entire life within the confines of East Prussia, but his thoughts traveled freely across Europe and, in time, to America, where their effects are still apparent. An untold number of analyses and commentaries have established Kant as a preeminent epistemologist, philosopher of science, moral philosopher, aestheti cian, and metaphysician. He is even recognized as a natural historian and cosmologist: the author of the so-called Kant-Laplace hypothesis regarding the origin of the universe. He is less often credited as a "psychologist," "anthropologist," or "philosopher of mind," to Work on this essay was supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant No. -

“Austrian” and “German” Philosophy in the 19Th Century

Christian Damböck (Dis-)Similarities: Remarks on “Austrian” and “German” Philosophy in the 19th Century In this paper, I re-examine Barry Smith’s 1994 list of features of Austrian Philosophy. I claim that the list properly applies only in a somewhat abbreviated form to all significant representatives of Austrian Philosophy. Moreover, Smith’s crucial thesis that the features of Austrian Philosophy are not shared by any German philosopher only holds if we compare Austrian Philosophy to a canonical list of Ger- man Philosophy II. This list, however, was established in 20th century as a result of historical misrep- resentations. If we correct these misrepresentations, we obtain another list of hidden representatives called German Philosophy I. German Philosophy I is fundamentally identical to Austrian Philosophy, whereas German Philosophy II is entirely different from both Austrian Philosophy and German Phi- losophy I. Therefore, a slightly modified version of Smith’s Austrian Philosophy account still makes sense as a tool to position the pro-scientific and rational currents of Austrian Philosophy and German Philosophy I against the tendentially anti-scientific and irrational current of German Philosophy II. Although Austria and Germany1 were independent nations in the 19th century, there are many aspects that overlap between the countries. Austria and Germany share the same language, and the borders between Austria and Germany were always more or less open for academics to move from one country to the other.2 Religious differences do exist, but they do not coincide with national borders. Whereas Austria is mainly Catholic and Germany is mainly Protestant, important parts of (southwestern) Germany are mainly Catholic as well. -

An Investigation Into a Postmodern Feminist Reading of Averroës

Journal of Feminist Scholarship Volume 10 Issue 10 Spring 2016 Article 5 Spring 2016 Bodies and Contexts: An Investigation into a Postmodern Feminist Reading of Averroës Reed Taylor University of Arkansas at Little Rock Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jfs Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Women's History Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Taylor, Reed. 2018. "Bodies and Contexts: An Investigation into a Postmodern Feminist Reading of Averroës." Journal of Feminist Scholarship 10 (Spring): 48-60. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jfs/vol10/ iss10/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Feminist Scholarship by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Taylor: Bodies and Contexts Bodies and Contexts: An Investigation into a Postmodern Feminist Reading of Averroës Reed Taylor, University of Arkansas at Little Rock Abstract: In this article, I contribute to the wider discourse of theorizing feminism in predominantly Muslim societies by analyzing the role of women’s political agency within the writings of the twelfth-century Islamic philosopher Averroës (Ibn Rushd, 1126–1198). I critically analyze Catarina Belo’s (2009) liberal feminist approach to political agency in Averroës by adopting a postmodern reading of Averroës’s commentary on Plato’s Republic. A postmodern feminist reading of Averroes’s political thought emphasizes contingencies and contextualization rather than employing a literal reading of the historical works. -

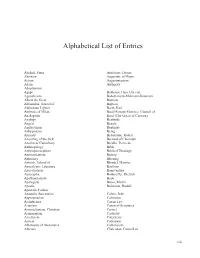

A-Z Entries List

Alphabetical List of Entries Abelard, Peter Attributes, Divine Abortion Augustine of Hippo Action Augustinianism Adam Authority Adoptionism Agape Balthasar, Hans Urs von Agnosticism Bañezianism-Molinism-Baianism Albert the Great Baptism Alexandria, School of Baptists Alphonsus Liguori Barth, Karl Ambrose of Milan Basel-Ferrara-Florence, Council of Anabaptists Basil (The Great) of Caesarea Analogy Beatitude Angels Beauty Anglicanism Beguines Anhypostasy Being Animals Bellarmine, Robert Anointing of the Sick Bernard of Clairvaux Anselm of Canterbury Bérulle, Pierre de Anthropology Bible Anthropomorphism Biblical Theology Antinomianism Bishop Antinomy Blessing Antioch, School of Blondel, Maurice Apocalyptic Literature Boethius Apocatastasis Bonaventure Apocrypha Bonhoeffer, Dietrich Apollinarianism Book Apologists Bucer, Martin Apostle Bultmann, Rudolf Apostolic Fathers Apostolic Succession Calvin, John Appropriation Calvinism Architecture Canon Law Arianism Canon of Scriptures Aristotelianism, Christian Carmel Arminianism Casuistry Asceticism Catechesis Aseitas Catharism Athanasius of Alexandria Catholicism Atheism Chalcedon, Council of xiii Alphabetical List of Entries Character Diphysitism Charisma Docetism Chartres, School of Doctor of the Church Childhood, Spiritual Dogma Choice Dogmatic Theology Christ/Christology Donatism Christ’s Consciousness Duns Scotus, John Chrysostom, John Church Ecclesiastical Discipline Church and State Ecclesiology Circumincession Ecology City Ecumenism Cleric Edwards, Jonathan Collegiality Enlightenment