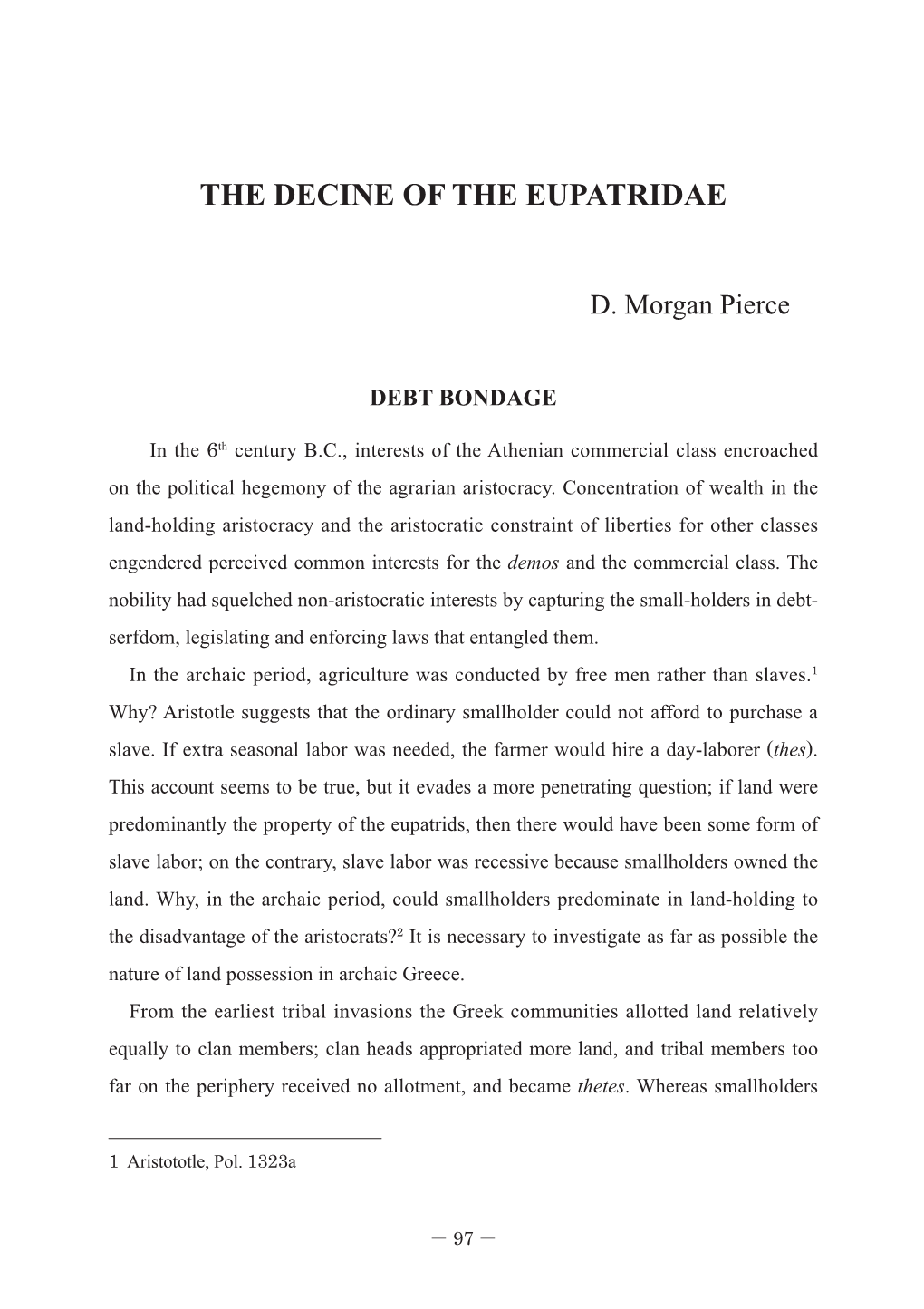

The Decine of the Eupatridae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greece--Selected Problems

REPORT RESUMES ED 013 992 24 AA 000 260 GREECE -- SELECTED PROBLEMS. BY- MARTONFFY, ANDREA PONTECORVO AND OTHERS CHICAGO UNIV., ILL. REPORT NUMBER BR-62445...1 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.50HC-$4.60 113F. DESCRIPTORS- *CURRICULUM GUIDES, *GREEK CIVILIZATION, *CULTURE, CULTURAL INTERRELATIONSHIPS,*PROBLEM SETS, *SOCIAL STUDIES, ANCIENT HISTORY, HIGH SCHOOL CURRICULUM A CURRICULUM GUIDE IS PRESENTED FOR A 10-WEEK STUDYOF ANCIENT GREEK CIVILIZATION AT THE 10TH -GRADE LEVEL.TEACHING MATERIALS FOR THE UNIT INCLUDE (1) PRIMARY ANDSECONDARY SOURCES DEALING WITH THE PERIOD FROM THE BRONZE AGETHROUGH THE HELLENISTIC PERIOD,(2) GEOGRAPHY PROBLEMS, AND (3) CULTURAL MODEL PROBLEM EXERCISES. THOSE CONCEPTSWITH WHICH THE STUDENT SHOULD GAIN MOST FAMILIARITY INCLUDETHE EXISTENCE OF THE UNIVERSAL CATEGORIES OF CULTURE(ECONOMICS, SOCIAL ORGANIZATION, POLITICAL ORGANIZATION,RELIGION, KNOWLEDGE, AND ARTS), THE INTERRELATEDNESS OF THESE CATEGORIES AT ANY GIVEN POINT IN TIME, AND THEINFLUENCE WHICH CHANGES IN ONE OF THESE MAY FLAY INPRECIPITATING LARGE -SCALE SOCIAL AND CULTURAL CHANGE. ANINTRODUCTION TO THE BIOLOGICAL DETERMINANTS (INDIVIDUAL GENETICCOMPOSITIONS) AND GEOGRAPHICAL DETERMINANTS (TOPOGRAPHY, CLIMATE,LOCATION, AND RESOURCES) OF GREEK CIVILIZATION IS PROVIDED.THE STUDENT IS ALSO INTRODUCED TO THE IDEA OF CULTURALDIFFUSION OR CULTURE BORROWING. (TC) .....Siiiir.i.......0.161,...4iliaalla.lilliW116,6".."`""_ GREECE:, SELEcT DPRO-BLES . Andrea POcorvoMartonffy& JOISApt, I. g ... EdgarBerwein, Geral Edi rs 4 CHICAGO SOCIALSTU i OJECT TRIAL EDITION Materials -

The Local Divisions of Attica

f\1e.7)u-tl ~-tS )~ ,\A l'i~~ The Local DiYieions of Attiea Before the t~e of Solon, Attica was organized by trittyes and phratries. The phratries were groups of famil ies related by blood, ·e.nd were divided, in turn, into ~~v,., , smaller associations united in loyalty to a mythical ancestor. Although from the inscriptions~ioh record the decrees of various Y I. vn , we knOlJ that by the time of Cleisthenes their me.mbers were scattered over various dames, it is probable that in the earlier period the y c v~ were connected with a defi.nite locality.1 The trittyes may have been divisi.ons of the Athenian people on the basis of locality but the evidence does not . 2 make this clear. The Eupatridae, who were pro_bably, as WS.de-Gery suggested, the descendants of these men who. formed the first c ouncil. of the Athenian state at the time of the synoecism of the twelve Attic towns, controlled the government in the pre-Solonean period.3 - 4 They .elected the flvA o a.~- e-. ;~. s from their own number, and chose the 5 nine archons. We can see, therefore, that political power in the pre-Solonean period Tms in the hands of groups of families in specific districts. The evidence that we have on the Attic y~v~ who looked after the cults on the acropolis and at Eleusi.s throws some light on the important place that the y l v~ had in Attic religion at this time. The Eteobou tadae, for instance, cared for the cult of Poseidon Erechtheus on the acropolis. -

Peter J. Rhodes Theseus the Democrat

Peter J. Rhodes Theseus the Democrat Miscellanea Anthropologica et Sociologica 15/3, 98-118 2014 Miscellanea Anthropologica et Sociologica 2014, 15 (3): 98–118 Peter J. Rhodes1 Theseus the Democrat2 It is remarkable that Athenians of the classical period believed that the first moves to- wards democracy in Athens had been made by their legendary king Theseus, whom they believed to have reigned before the Trojan War. In this paper, in an exercise in how the Athenians refashioned what they believed about their past, I trace the development of the political aspects of the story of Theseus, and try to explain how he came to be seen by the democrats of the classical period as an ur-democrat. Key words: Theseus, Greece, Athens, Trojan War, democrat 1 Durham Univesity; [email protected]. 2 This paper was written for a series on mythology at the University of Gdańsk, and read also at the Universities of Toruń, Erlangen–Nürnberg and Erfurt. I thank Prof. N. Sekunda of Gdańsk, Prof. D. Musiał of Toruń, Prof. B. Dreyer of Erlangen, Prof. K. Brodersen of Erfurt and their colleagues and students; also those whom I visited and to whom I spoke on other subjects at the Universities of Warsaw and Cracow in June 2011, and all who have been involved in the publication of this paper here. A Polish translationThis of copy a version is of thisfor paper personal has been published use onlyas Tezeusz - Demokratadistribution in prohibited. “Klio” (Rhodes 2012: 3–28). I thank Prof. Musiał for offering to publish that, and Dr. -

Aeschylus and Euripides on Orestes' Crimes

25th IVR World Congress LAW SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Frankfurt am Main 15–20 August 2011 Paper Series No. 099 / 2012 Series D History of Philosophy; Hart, Kelsen, Radbruch, Habermas, Rawls; Luhmann; General Theory of Norms, Positivism Felipe Magalhães Bambirra / Gabriel Lago de Sousa Barroso Crisis and Philosophy: Aeschylus and Euripides on Orestes’ Crimes URN: urn:nbn:de:hebis:30:3-249572 This paper series has been produced using texts submitted by authors until April 2012. No responsibility is assumed for the content of abstracts. Conference Organizers: Edited by: Professor Dr. Dr. h.c. Ulfrid Neumann, Goethe University Frankfurt am Main Goethe University, Frankfurt/Main Department of Law Professor Dr. Klaus Günther, Goethe Grüneburgplatz 1 University, Frankfurt/Main; Speaker of 60629 Frankfurt am Main the Cluster of Excellence “The Formation Tel.: [+49] (0)69 - 798 34341 of Normative Orders” Fax: [+49] (0)69 - 798 34523 Professor Dr. Lorenz Schulz M.A., Goethe University, Frankfurt/Main Felipe Magalhães Bambirra* and Gabriel Lago de Sousa Barroso**, Belo Horizonte / Brazil Crisis and Philosophy: Aeschylus and Euripides on Orestes’ Crimes Abstract : Since the XIX century, a pleiad of philosophers and historians support the idea that Greek philosophy, usually reported to have started with the presocratics, lays its basis in a previous moment: the Greek myths – systematized by Homer and Hesiod – and the Greek arts, in particular the lyric and tragedy literature. According to this, it is important to retrieve philosophical elements even before the pre-Socratics to understand the genesis of specific concepts in Philosophy of Law. Besides, assuming that the Western’s core values are inherited from Ancient Greece, it is essential to recuperate the basis of our own justice idea, through the Greek myths and tragedy literature. -

Western Civ. Id

Western Civ. Id The Age of Pericles Greek Thought Alexander the Great The Hellenistic World and The Athenian Empire Page 5 Page 9 Page 13 Page 17 THE RISE OF ATHENS Today, we must look at the second great polis, that of the Athenians. As we did in the case of Sparta, we must first look at the geography of Athens and the influence of that geography on her growth. The territory of the Athenians occupied a rocky peninsula in central Greece called Attica. Unlike Laconia, the Spartan homeland, the area of Attica included very little good farmland. It was generally a poor region except for silver. The city of Athens itself was about five miles from the coast, but it was near enough to use several good harbors in her territory. This meant that if Athens were to become an important state, she would have to rely on trade rather than farming. Before 500 B.C. when Athenian trade was still limited, the polis remained backward and relatively weak. But as her trade developed after 500, she became one of the most powerful and most progressive of all the Greek city-states. The dialect of Attica is closely related to the Ionian (Iconic) dialects. This means that the original population of Attica were predominately Mycenaean Greeks who lived in Attica before the start of the Iron Age. Evidence about the earliest organization of the Athenian polis is limited, but there is enough information to give at least some idea of the conditions there. As I suggested above, Athens remained relatively backward during her early history. -

H408/34 Democracy and the Athenians Sample Question Paper

A Level Classical Civilisation H408/34 Democracy and the Athenians Sample Question Paper Date – Morning/Afternoon Time allowed: 1 hour 45 minutes You must have: • Answer Booklet * 0 0 0 0 0 0 * INSTRUCTIONS • Use black ink. • Complete the boxes on the Answer Booklet with your name, centre number and candidate number. • Answer all of Section A and one question from Section B. • Read each question carefully. Make sure you know what you have to do before starting your answer. • Write your answer to each question in the space provided. • Write the number of each question answered in the margin. • Do not write in the bar codes. INFORMATION SPECIMEN • The total mark for this paper is 75. • The marks for each question are shown in brackets [ ]. • Quality of extended response will be assessed in questions marked with an asterisk (*). • This document consists of 4 pages. © OCR 2016 H408/34 Turn over 603/0726/2 C10043/1.7 2 Section A Answer all questions in this section. Source A: Aristophanes, Knights, 255-65 Paphlagonian: Ouch, ouch! Ohhhh! Help! Friends, elder jurors, brothers of the courts, whose wages I’ve increased to three obols a day –three! - and whose business I’ve helped grow with lots and lots of judgements. Good judgements or bad, it made no difference to me! I just shouted them out and passed them on to you! Come, help me! The conspirators are beating me up! Ouch, ouch, Oh! Help me! 5 Leader of the Chorus: Too right! Of course we are! You’re a thief, a crook, an embezzler! You strip the public purse bare even before you get elected. -

|||GET||| the Oresteia Agamemnon; the Libation Bearers; The

THE ORESTEIA AGAMEMNON; THE LIBATION BEARERS; THE EUMENIDES 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Aeschylus | 9780140443332 | | | | | The Oresteia: Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers, The Eumenides Personally, I think it was just a political move. He is the earliest of the three Greek tragedians whose plays survive extant, the others being Sophocles and Euripides. Ted Hughes Translator. The first play, "Agamemnon", is about betrayal: King Agamemnon returns home to Argos after the successful sacking of Troy in modern-day Turkeyonly to be killed by his wife Clytemnestra and Oresteia is the only surviving trilogy of Greek tragedy plays, performed in BCE - two years before Aeschylus's death in BCE. Get A Copy. Trivia About The Oresteia: Aga The chorus is addressing the assembled audience, certainly, and the Gods and Furies are or can be as well. Home from the pyres he sends them, home from Troy to the loved ones, heavy with tears, the urns brimmed full, the heroes return in gold-dust, dear, light ash for men: and they weep, they praise them, 'He had skill in the swordplay, 'He went down so tall in the onslaught,' 'All for another's woman. The Oresteian trilogy: Agamemmon, the Choephori, the Eumenides. His play The Persians remains a good primary source of The Oresteia Agamemnon; The Libation Bearers; The Eumenides 1st edition about this period in Greek history. I did, naturally, intend to suggest that Shakespeare if that IS his real name bogarted some lines from Aeschylus. This naval battle holds a prominent place in The Persians, his oldest surviving play, which was performed in BC and The Oresteia Agamemnon; The Libation Bearers; The Eumenides 1st edition first prize at the Dionysia. -

A CLOSER LOOK at the ALCMAEONIDAE by CAROL

A CLOSER LOOK AT_THE ALCMAEONIDAE By CAROL BOUNDS BROEMELING JI Bachelor of Arts Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1970 Submitted to the Faculty of the ·Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS December, 1973 OKLAHOMA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY APR 9 1974 A CLOSER LOOK AT THE ALCMAEONIDAE Thesis Approved: Dean of the Graduate College ii PREFACE As an undergraduate encountering the history of·Greece for the first time, I was struck by the exciting and often bizzare quality of the the events which formed the nucleus of the history of Athens. Reading the accounts and interpretations.of the struggle over tyranny, the emergence of democracy, and the conflicts with Persia and Sparta, I nottced.that.while much remained unknown about these events, it was well. established that many of the leading individuals were members of a.family known as the Alcmaeonidae. Moreover, their role was considered so vital by most historians that even .when individual leaders.could not be identi-: fied, writers felt free to credit the family with exerting a major in fluence on the events which det~rmined the history of Athens from the seventh to the late fifth century. This assertion of their importance in Athenian history was acc9mpan;i:ed in most cases, by the inference that the conduct of the family was.something le13'S than admirable. Any attempt to study this family is hampered by many of the same basic difficulties which confront most historical inquiry. Sources of factual.information must.be discovered and evaluated, Due to the expanse of time which separates us from the events, this problem is compounded. -

The Athenian Βαζηιεύο to 323

The Athenian Βαζηιεύο to 323 BCE —Myth and Reality Kevin James O‘Toole B.Ec., Dip.Ed., B.Sc., LL.B. Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Western Australia School of Humanities Discipline Group of Classics and Ancient History 2012 The Athenian Βαζηιεύο to 323 BCE —Myth and Reality Kevin James O‘Toole ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I gratefully acknowledge the always generous, good-humoured and pertinent advice to me throughout the present project of Professor John Melville-Jones. I also gratefully acknowledge the advice and encouragement of Dr Lara O‘Sullivan. I take the opportunity also to express my appreciation of the Reid Library at the University of Western Australia in particular for giving me efficient access to the world‘s libraries through its inter-library service. K. J. O‘Toole For Helen and for our children Nicholas, Dominic and Stephanie 3 ABSTRACT The recent more critical analysis of the ancient sources that has led to broad acceptance by modern scholars that there was no ancestral monarchy in geometric Athens of a type comparable to monarchies to the contemporaneous east and south-east of the Aegean, needs also to be applied to the traditional account of the office of the annual Athenian βαζηιεύο. The absence of ancestral monarchy itself calls for a review of the traditional account of the origins of the office of the annual Athenian βαζηιεύο, based as it is on a genesis from such a monarchy. The notion that the βαζηιεύο was ―the successor of the Bronze Age kings‖ is not sustained by a review of such Bronze Age evidence that there is. -

Brainy Quote ~ Aeschylus 018

Brainy Quote ~ Aeschylus 018 “Whenever a man makes haste, God too hastens with him.” ~ Aeschylus 018 ~ Ok "Setiap kali seorang manusia bergegas, Tuhan juga bergegas bersamanya." ~ Aeschylus 018 ~ Ok Pernahkah Anda berencana melakukan sesuatu dengan segera?! Ketika Anda bersama anggota keluarga atau anggota tim dalam pekerjaan, apakah mereka juga akan mengikuti kemauan Anda dengan segera? Mungkin iya, mungkin juga tidak! Bila anggota keluarga atau tim Anda mengerti dan memahani tujuan Anda, mereka mungkin mengikuti irama hidup Anda. Bila tidak, mereka kemungkinan akan mengabaikannya. Namun, tidak demikian dengan Sang Maha Pencipta. Tuhan akan bergegas bersama manusia yang bergegas melakukan pekerjaannya. Seperti yang pernah diutarakan Aeschylus, seorang Tragedian Yunani terkemuka, hidup dalam rentang tahun 525 – 456 BC (69 tahun), lewat quote-nya, ‘Whenever a man makes haste, God too hastens with him.’ Secara bebas diterjemahkan, ‘Setiap kali seorang manusia bergegas, Tuhan juga bergegas bersamanya.’ Tuhan itu maha adil. Ia menselaraskan berkatnya dengan manusia yang berusaha. Dia selalu hadir untuk manusia yang bergegas melakukan pekerjaan yang baik dan benar. Namun, seringkali manusia salah menafsirkan perilaku Tuhan. Menurut mereka, cukup dengan berdoa, maka berkat akan berlimpah bagi hidup mereka. Padahal, Tuhan tidak demikian. Ia senantiasa ada bagi setiap orang yang mendekatkan diri pada-Nya, sekaligus bekerja secara optimal. Bagi yang tidak, Tuhan menunggu sampai manusia merasakan kembali kehadiran-Nya. Ora et labora! Berdoa dan bekerja. Bergegaslah untuk berkarya. Jangan menunda. Bila manusia menunda, Tuhan pun demikian. Bila manusia bergegas, Tuhan pun demikian. Ia selaras dengan usaha kita. Usaha 100% akan diberi berkat 100%. Usaha separuh akan didiberkati separuh. Talenta 1 akan menjadi 2. Talenta 2 akan menjadi 4. -

Some Problems in the Athenian Strategia of the Fifth Century B.C

SOME PROBLEMS IN IHE ATHENIAN STRATEGIA OF THE FIFTH CENTURY B.C. by IETER IAN HENNING, B.A. s) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF TASMANIA HOBART December 1974. To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university, and contains no copy or paraphrase of material previously published or written by another person except when due reference is made in the text of the thesis. CONTENTS Page •• Abbreviations • • •• iv. Abstract • • •• 1 PART I CHAPTER 1. Ath Pa 22.2 and the Reform of 501/0. 3 CHAPTER 2. Hegemonia and the Command at Marathon 23 CHAPTER 3. Election Procedure 47 PART II CHAPTER 4. The Persian Invasion 480/78 •• 89 CHAPTER 5. Double Representation and the Strategos ex hapanton 113 CHAPTER 6. The Size of the Board .. •• 139 CHAPTER 7. Terminologies in the Sources 180 PART III APPENDIX. 1. List of Generals 211 2. The Strategia - Its Nature and Powers .. .. .. 238 3. Term of Office .. .., 258 4. Possible Double Representations 268 Notes to the Text •• •• 274 Bibliography • • • • •• 339 Abbreviations. I include abbreviations of periodicals and standard reference works in addition to my own special abbreviations of works which have been frequently adverted to in the text and notes. Ant. Class. L'Antiquite classique. AJP American Journal of'Philology. Ath Pal Aristotle, Athenaion Politeia. ATL Meritt, B.D., - Wade - Gery, H.T., - McGregor, , The Athenian Tribute Lists, Cambridge (Mass.), Vol.1, Princeton, vols. -

From Gennetai to Curiales

FROM GENNETAI TO CURIALES (PLATE 2) A MONG THE AGORA INSCRIPTIONS that of the Gephyraeifrom the time of Mark Antony seems to connect with its background and promise the problems of the 6th century B.C. and those of the Late Roman Empire. It leads in both direc- tions if one considers the questions it raises, first about the Athenian military-political organization before the Reforms of Cleisthenes, secondly about the new kind of genos found in Roman Athens, one which may have had an unexpected similarity of purpose with the curiae of North African cities. The question finally leads the student into the meaning of the word curiales. The title " From Gennetai to Curiales " best ex- presses the subject, which is both a new edition of a well-publishedbut important text and an investigation into a basic early institution in the background and into the his- tory of an idea down to the late 3rd or 4th century after Christ. I. THE ATHENIAN ORGANIZATION OF THE 6TH CENTURY B.C. At least one piece of evidence for the levy in the 6th century has not previously been weighed despite the prevailing opinion that all the evidence on early Athens has been exhaustively studied. Recently A. M. Snodgrass in several works, M. Detienne in his article " La phalange " among J.-P. Vernant's Problemes de la guerre en Gr&ce ancienne, Paris-the Hague 1968, and R. Drews in a penetrating study of the first tyrants, Historia 21, 1972, pp. 129-144, have filled out the stages in the hoplite revolu- tion but have left room for a further treatment of the change from a hoplite elite and epikouroi to a hoplite demos in Attica.