It's Just a Phase!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Understanding Condensation

Guide to Understanding Condensation The complete Andersen® Owner-To-Owner™ limited warranty is available at: www.andersenwindows.com. “Andersen” is a registered trademark of Andersen Corporation. All other marks where denoted are marks of Andersen Corporation. © 2007 Andersen Corporation. All rights reserved. 7/07 INTRODUCTION 2 The moisture that suddenly appears in cold weather on the interior We have created this brochure to answer questions you may have or exterior of window and patio door glass can block the view, drip about condensation, indoor humidity and exterior condensation. on the floor or freeze on the glass. It can be an annoying problem. We’ll start with the basics and offer solutions and alternatives While it may seem natural to blame the windows or doors, interior along the way. condensation is really an indication of excess humidity in the home. Exterior condensation, on the other hand, is a form of dew — the Should you run into problems or situations not covered in the glass simply provides a surface on which the moisture can condense. following pages, please contact your Andersen retailer. The important thing to realize is that if excessive humidity is Visit the Andersen website: www.andersenwindows.com causing window condensation, it may also be causing problems elsewhere in your home. Here are some other signs of excess The Andersen customer service toll-free number: 1-888-888-7020. humidity: • A “damp feeling” in the home. • Staining or discoloration of interior surfaces. • Mold or mildew on surfaces or a “musty smell.” • Warped wooden surfaces. • Cracking, peeling or blistering interior or exterior paint. -

Chapter 3 Bose-Einstein Condensation of an Ideal

Chapter 3 Bose-Einstein Condensation of An Ideal Gas An ideal gas consisting of non-interacting Bose particles is a ¯ctitious system since every realistic Bose gas shows some level of particle-particle interaction. Nevertheless, such a mathematical model provides the simplest example for the realization of Bose-Einstein condensation. This simple model, ¯rst studied by A. Einstein [1], correctly describes important basic properties of actual non-ideal (interacting) Bose gas. In particular, such basic concepts as BEC critical temperature Tc (or critical particle density nc), condensate fraction N0=N and the dimensionality issue will be obtained. 3.1 The ideal Bose gas in the canonical and grand canonical ensemble Suppose an ideal gas of non-interacting particles with ¯xed particle number N is trapped in a box with a volume V and at equilibrium temperature T . We assume a particle system somehow establishes an equilibrium temperature in spite of the absence of interaction. Such a system can be characterized by the thermodynamic partition function of canonical ensemble X Z = e¡¯ER ; (3.1) R where R stands for a macroscopic state of the gas and is uniquely speci¯ed by the occupa- tion number ni of each single particle state i: fn0; n1; ¢ ¢ ¢ ¢ ¢ ¢g. ¯ = 1=kBT is a temperature parameter. Then, the total energy of a macroscopic state R is given by only the kinetic energy: X ER = "ini; (3.2) i where "i is the eigen-energy of the single particle state i and the occupation number ni satis¯es the normalization condition X N = ni: (3.3) i 1 The probability -

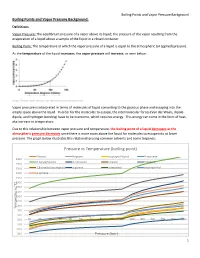

Pressure Vs Temperature (Boiling Point)

Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background: Definitions Vapor Pressure: The equilibrium pressure of a vapor above its liquid; the pressure of the vapor resulting from the evaporation of a liquid above a sample of the liquid in a closed container. Boiling Point: The temperature at which the vapor pressure of a liquid is equal to the atmospheric (or applied) pressure. As the temperature of the liquid increases, the vapor pressure will increase, as seen below: https://www.chem.purdue.edu/gchelp/liquids/vpress.html Vapor pressure is interpreted in terms of molecules of liquid converting to the gaseous phase and escaping into the empty space above the liquid. In order for the molecules to escape, the intermolecular forces (Van der Waals, dipole- dipole, and hydrogen bonding) have to be overcome, which requires energy. This energy can come in the form of heat, aka increase in temperature. Due to this relationship between vapor pressure and temperature, the boiling point of a liquid decreases as the atmospheric pressure decreases since there is more room above the liquid for molecules to escape into at lower pressure. The graph below illustrates this relationship using common solvents and some terpenes: Pressure vs Temperature (boiling point) Ethanol Heptane Isopropyl Alcohol B-myrcene 290.0 B-caryophyllene d-Limonene Linalool Pulegone 270.0 250.0 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol) a-pinene a-terpineol terpineol-4-ol 230.0 p-cymene 210.0 190.0 170.0 150.0 130.0 110.0 90.0 Temperature (˚C) Temperature 70.0 50.0 30.0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 200 300 400 500 600 760 10.0 -10.0 -30.0 Pressure (torr) 1 Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background As a very general rule of thumb, the boiling point of many liquids will drop about 0.5˚C for a 10mmHg decrease in pressure when operating in the region of 760 mmHg (atmospheric pressure). -

Capillary Condensation of Colloid–Polymer Mixtures Confined

INSTITUTE OF PHYSICS PUBLISHING JOURNAL OF PHYSICS: CONDENSED MATTER J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 15 (2003) S3411–S3420 PII: S0953-8984(03)66420-9 Capillary condensation of colloid–polymer mixtures confined between parallel plates Matthias Schmidt1,Andrea Fortini and Marjolein Dijkstra Soft Condensed Matter, Debye Institute, Utrecht University, Princetonplein 5, 3584 CC Utrecht, The Netherlands Received 21 July 2003 Published 20 November 2003 Onlineatstacks.iop.org/JPhysCM/15/S3411 Abstract We investigate the fluid–fluid demixing phase transition of the Asakura–Oosawa model colloid–polymer mixture confined between two smooth parallel hard walls using density functional theory and computer simulations. Comparing fluid density profiles for statepoints away from colloidal gas–liquid coexistence yields good agreement of the theoretical results with simulation data. Theoretical and simulation results predict consistently a shift of the demixing binodal and the critical point towards higher polymer reservoir packing fraction and towards higher colloid fugacities upon decreasing the plate separation distance. This implies capillary condensation of the colloid liquid phase, which should be experimentally observable inside slitlike micropores in contact with abulkcolloidal gas. 1. Introduction Capillary condensation denotes the phenomenon that spatial confinement can stabilize a liquid phase coexisting with its vapour in bulk [1, 2]. In order for this to happen the attractive interaction between the confining walls and the fluid particles needs to be sufficiently strong. Although the main body of work on this subject has been done in the context of confined simple liquids, one might expect that capillary condensation is particularly well suited to be studied with colloidal dispersions. In these complex fluids length scales are on the micron rather than on the ångstrom¨ scale which is typical for atomicsubstances. -

Lecture 11. Surface Evaporation and Soil Moisture (Garratt 5.3) in This

Atm S 547 Boundary Layer Meteorology Bretherton Lecture 11. Surface evaporation and soil moisture (Garratt 5.3) In this lecture… • Partitioning between sensible and latent heat fluxes over moist and vegetated surfaces • Vertical movement of soil moisture • Land surface models Evaporation from moist surfaces The partitioning of the surface turbulent energy flux into sensible vs. latent heat flux is very important to the boundary layer development. Over ocean, SST varies relatively slowly and bulk formulas are useful, but over land, the surface temperature and humidity depend on interactions of the BL and the surface. How, then, can the partitioning be predicted? For saturated ideal surfaces (such as saturated soil or wet vegetation), this is relatively straight- forward. Suppose that the surface temperature is T0. Then the surface mixing ratio is its saturation value q*(T0). Let z1 denote a measurement height within the surface layer (e. g. 2 m or 10 m), at which the temperature and humidity are T1 and q1. The stability is characterized by an Obhukov length L. The roughness length and thermal roughness lengths are z0 and zT. Then Monin-Obuhkov theory implies that the sensible and latent heat fluxes are HS = ρLvCHV1 (T0 - T1), HL = ρLvCHV1 (q0 - q1), where CH = fn(V1, z1, z0, zT, L)" We can eliminate T0 using a linearized version of the Clausius-Clapeyron equations: q0 - q*(T1) = (dq*/dT)R(T0 - T1), (R indicates a reference temp. near (T0 + T1)/2) HL = s*HS +!LCHV1(q*(T1) - q1), (11.1) s* = (L/cp)(dq*/dT)R (= 0.7 at 273 K, 3.3 at 300 K) This equation expresses latent heat flux in terms of sensible heat flux and the saturation deficit at the measurement level. -

Alside Condensation Guide Download

Condensation Your Guide To Common Household Condensation C Understanding Condensation Common household condensation, or “sweating” on windows is caused by excess humidity or water vapor in a home. When this water vapor in the air comes in contact with a cold surface such as a mirror or window glass, it turns to water droplets and is called condensation. Occasional condensation, appearing as fog on the windows or glass surfaces, is normal and is no cause for concern. On the other hand, excessive window Conquering the Myth . Windows Ccondensation, frost, peeling paint, or Do Not Cause Condensation. moisture spots on ceilings and walls can be signs of potentially damaging humidity You may be wondering why your new levels in your home. We tend to notice energy-efficient replacement windows show condensation on windows and mirrors first more condensation than your old drafty ones. because moisture doesn’t penetrate these Your old windows allowed air to flow between surfaces. Yet they are not the problem, simply the inside of your home and the outdoors. the indicators that you need to reduce the Your new windows create a tight seal between indoor humidity of your home. your home and the outside. Excess moisture is unable to escape, and condensation becomes visible. Windows do not cause condensation, but they are often one of the first signs of excessive humidity in the air. Understanding Condensation Where Does Indoor Outside Recommended Humidity Come From? Temperature Relative Humidity All air contains a certain amount of moisture, +20°F 30% - 35% even indoors. And there are many common +10°F 25% - 30% things that generate indoor humidity such as your heating system, humidifiers, cooking and 0°F 20% - 25% showers. -

Preventing Condensation

Preventing condensation Preventing condensation Consider conditions of condensation, for example, a room or warehouse where the air is 27°C (80°F) and • What causes condensation? the relative humidity is 75%. In this room, any object • How can conditions of condensation be anticipated? with a temperature of 22°C (71°F) or lower will become • What can be done to prevent condensation? covered by condensation. Unwanted condensation on products or equipment How can conditions of condensation be anticipated? can have consequences. Steel and other metals stored The easiest way to anticipate condensing conditions in warehouses can corrode or suffer surface damage as is to measure the dew point temperature in the area a result of condensation. Condensation on packaged of interest. This can be done simply with a portable beverage containers can damage labels or cardboard indicator, or a fixed transmitter can be used to track packaging materials. Water-cooled equipment, such dew point temperature full-time. The second piece of as blow molding machinery, can form condensation information required is the temperature of the object on critical surfaces that impair product quality or the that is to be protected from condensation. In all cases, productivity of the equipment. How can we get a grip as the dew point temperature reaches the object’s on this potential problem? temperature, condensation on the object is imminent. The best way to capture an object’s temperature is dependent on the specific application. For example, What causes condensation? water-cooled machinery may already provide a display or output of coolant temperature (and therefore, a Condensation will form on any object when the close approximation of the temperature of the object temperature of the object is at or below the dew that is being cooled). -

Chapter 3 Moist Thermodynamics

Chapter 3 Moist thermodynamics In order to understand atmospheric convection, we need a deep understand- ing of the thermodynamics of mixtures of gases and of phase transitions. We begin with a review of some of the fundamental ideas of statistical mechanics as it applies to the atmosphere. We then derive the entropy and chemical potential of an ideal gas and a condensate. We use these results to calcu- late the saturation vapor pressure as a function of temperature. Next we derive a consistent expression for the entropy of a mixture of dry air, wa- ter vapor, and either liquid water or ice. The equation of state of a moist atmosphere is then considered, resulting in an expression for the density as a function of temperature and pressure. Finally the governing thermody- namic equations are derived and various alternative simplifications of the thermodynamic variables are presented. 3.1 Review of fundamentals In statistical mechanics, the entropy of a system is proportional to the loga- rithm of the number of available states: S(E; M) = kB ln(δN ); (3.1) where δN is the number of states available in the internal energy range [E; E + δE]. The quantity M = mN=NA is the mass of the system, which we relate to the number of molecules in the system N, the molecular weight of these molecules m, and Avogadro’s number NA. The quantity kB is Boltz- mann’s constant. 35 CHAPTER 3. MOIST THERMODYNAMICS 36 Consider two systems in thermal contact, so that they can exchange en- ergy. The total energy of the system E = E1 + E2 is fixed, so that if the energy of system 1 increases, the energy of system 2 decreases correspond- ingly. -

Understanding Vapor Diffusion and Condensation

uilding enclosure assemblies temperature is the temperature at which the moisture content, age, temperature, and serve a variety of functions RH of the air would be 100%. This is also other factors. Vapor resistance is commonly to deliver long-lasting sepa- the temperature at which condensation will expressed using the inverse term “vapor ration of the interior building begin to occur. permeance,” which is the relative ease of environment from the exteri- The direction of vapor diffusion flow vapor diffusion through a material. or, one of which is the control through an assembly is always from the Vapor-retarding materials are often Bof vapor diffusion. Resistance to vapor diffu- high vapor pressure side to the low vapor grouped into classes (Classes I, II, III) sion is part of the environmental separation; pressure side, which is often also from the depending on their vapor permeance values. however, vapor diffusion control is often warm side to the cold side, because warm Class I (<0.1 US perm) and Class II (0.1 to primarily provided to avoid potentially dam- air can hold more water than cold air (see 1.0 US perm) vapor retarder materials are aging moisture accumulation within build- Figure 2). Importantly, this means it is not considered impermeable to near-imperme- ing enclosure assemblies. While resistance always from the higher RH side to the lower able, respectively, and are known within to vapor diffusion in wall assemblies has RH side. the industry as “vapor barriers.” Some long been understood, ever-increasing ener- The direction of the vapor drive has materials that fall into this category include gy code requirements have led to increased important ramifications with respect to the polyethylene sheet, sheet metal, aluminum insulation levels, which in turn have altered placement of materials within an assembly, foil, some foam plastic insulations (depend- the way assemblies perform with respect to and what works in one climate may not work ing on thickness), and self-adhered (peel- vapor diffusion and condensation control. -

Recap: First Law of Thermodynamics Joule: 4.19 J of Work Raised 1 Gram Water by 1 ºC

Recap: First Law of Thermodynamics Joule: 4.19 J of work raised 1 gram water by 1 ºC. This implies 4.19 J of work is equivalent to 1 calorie of heat. • If energy is added to a system either as work or as heat, the internal energy is equal to the net amount of heat and work transferred. • This could be manifest as an increase in temperature or as a “change of state” of the body. • First Law definition: The increase in internal energy of a system is equal to the amount of heat added minus the work done by the system. ΔU = increase in internal energy ΔU = Q - W Q = heat W = work done by system Note: Work done on a system increases ΔU. Work done by system decreases ΔU. Change of State & Energy Transfer First law of thermodynamics shows how the internal energy of a system can be raised by adding heat or by doing work on the system. U -W ΔU = Q – W Q Internal Energy (U) is sum of kinetic and potential energies of atoms /molecules comprising system and a change in U can result in a: - change on temperature - change in state (or phase). • A change in state results in a physical change in structure. Melting or Freezing: • Melting occurs when a solid is transformed into a liquid by the addition of thermal energy. • Common wisdom in 1700’s was that addition of heat would cause temperature rise accompanied by melting. • Joseph Black (18th century) established experimentally that: “When a solid is warmed to its melting point, the addition of heat results in the gradual and complete liquefaction at that fixed temperature.” • i.e. -

Condensation Information October 2016

Sun Windows General Information Section 1 Condensation Information October 2016 Condensation Every year, with the arrival of cold, winter weather, questions about condensation arise. The moisture that forms on window glass, obscuring the view, freezing or even collecting in puddles on the window sill, can be irritating and possibly even damaging. The first reaction may be to blame the windows for this problem, yet windows do not cause condensation. Excessive water vapor in the air, the temperature of the air and air circulation or movement are the three factors involved in the formation of condensation. Today’s modern homes are built very “air-tight” for energy efficiency. They provide better insulating properties and a cleaner, more comfortable living environment than older homes. These improvements in home design and construction have created some new problems as well. The more “air-tight” a home is the less fresh air that home circulates. A typical central air and heat system only circulates the air already within the home. This air becomes saturated with by-products of normal living. One of these is water vapor. Excessive water vapor in the home will most likely show up as condensation on windows. Condensation on your windows is a warning sign that the relative humidity (the measure of water vapor in the air) in your home is too high. You may see it develop on your windows, but it may be damaging the structural components and finishes through-out your home. It can also be damaging to your health. The following review should answer many questions concerning condensation and provide good information that will help in controlling condensation. -

Lecture 8 Phases, Evaporation & Latent Heat

LECTURE 8 PHASES, EVAPORATION & LATENT HEAT Lecture Instructor: Kazumi Tolich Lecture 8 2 ¨ Reading chapter 17.4 to 17.5 ¤ Phase equilibrium ¤ Evaporation ¤ Latent heats n Latent heat of fusion n Latent heat of vaporization n Latent heat of sublimation Phase equilibrium & vapor-pressure curve 3 ¨ If a substance has two or more phases that coexist in a steady and stable fashion, the substance is in phase equilibrium. ¨ The pressure of the gas when equilibrium is reached is called equilibrium vapor pressure. ¨ A plot of the equilibrium vapor pressure versus temperature is called vapor-pressure curve. ¨ A liquid boils at the temperature at which its vapor pressure equals the external pressure. Phase diagram 4 ¨ A fusion curve indicates where the solid and liquid phases are in equilibrium. ¨ A sublimation curve indicates where the solid and gas phases are in equilibrium. ¨ A plot showing a vapor-pressure curve, a fusion curve, and a sublimation curve is called a phase diagram. ¨ The vapor-pressure curve comes to an end at the critical point. Beyond the critical point, there is no distinction between liquid and gas. ¨ At triple point, all three phases, solid, liquid, and gas, are in equilibrium. ¤ In water, the triple point occur at T = 273.16 K and P = 611.2 Pa. Quiz: 1 5 ¨ In most substance, as the pressure increases, the melting temperature of the substance also increases because a solid is denser than the corresponding liquid. But in water, ice is less dense than liquid water. Does the fusion curve of water have a positive or negative slope? A.