National Foreign Trade Policy of India: Focus on Development Dimensions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ipe Global Limited, New Delhi Policy on Prevention of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse A

IPE GLOBAL LIMITED, NEW DELHI POLICY ON PREVENTION OF SEXUAL EXPLOITATION AND ABUSE A. GENERAL IPE Global Limited (IPE Global) (hereinafter referred to as “the Company”) places human dignity at the centre of its development work. The Company takes seriously all concerns about sexual exploitation and abuse and complaints about them brought to our attention. The Company initiates rigorous investigation of complaints that indicate a possible violation of this Policy on Prevention of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (“the Policy”) and takes appropriate disciplinary action, as warranted. This policy applies to complaints of sexual exploitation and abuse involving IPE Global employees and related-personnel. B. REFERENCES 1. IPE Global – Child Protection Policy. C. PURPOSE The purpose of this Policy is to provide guidance on prevention of sexual exploitation and abuse issues and making the staff members including project team members (including entire workforce as defined under D. SCOPE) aware of their responsibilities/ duties this Policy places on them towards third parties, referred to as “beneficiary” populations , in order to ensure the integrity of IPE Global’s activities. D. SCOPE This policy applies to the complaints of sexual exploitation and abuse involving entire workforce in the Company involving employees, whatever their status (including those on contract), subcontractors, sub- consultants, and/ or any other parties having business relations with the Company. Also, this policy applies to all branch offices and subsidiaries –IPE Global Centre for Knowledge and Development (IPE CKD), India; Ajooni Impact Investment Advisors Private Limited, India; Triple Line Consulting Limited, United Kingdom; IPE Global (Africa) Limited, Kenya; and branch offices in Ethiopia, Philippines, Myanmar, Nepal, and Bangladesh. -

DESIGNATION HR BUSINESS PARTNER LOCATION New Delhi

DESIGNATION HR BUSINESS PARTNER LOCATION New Delhi ABOUT IPE IPE Global Limited (IPE Global) is an international development consultancy group providing expert GLOBAL technical assistance in developing countries. The group partners with multilateral and bilateral agencies, governments, corporates and not-for-profit entities in anchoring development agenda for equitable development and sustainable growth. Headquartered in India with four international offices in United Kingdom, Kenya, Ethiopia and Bangladesh, the group offers a range of integrated, innovative and high quality consulting services across several sectors and practices. The organization has multi-disciplinary team of professionals, bringing together the right skills and technical expertise for enriching lives in poor and developing countries. Our experts work closely with program stakeholders and clients to co-design solutions for complex socioeconomic issues. We strive to create enabling environment for path breaking social and policy reforms that contribute to sustainable development. For more details, please visit www.ipeglobal.com JOB DESCRIPTION IPE Global is inviting applications for the position of HR Business Partner. The incumbent would be responsible for aligning business objectives with employees and management in designated business units. The position serves as a consultant to management on human resource-related issues. The role assesses and anticipates HR-related needs. Communicating needs proactively with our HR department and business management, the HRBP seeks to develop integrated solutions. The position formulates partnerships across the HR function to deliver value-added service to management and employees that reflects the business objectives of the organization. The HRBP maintains an effective level of business literacy about the business unit's financial position, its midrange plans, its culture and its competition. -

Evaluation of Impacts of the Development Capital Investment Intervention of the DFID India’S Private Sector Infrastructure Portfolio

Evaluation of impacts of the Development Capital Investment Intervention of the DFID India’s Private Sector Infrastructure Portfolio Draft Final Baseline Report Aug 2019 Submitted by: Author This evaluation report is prepared by the Evaluation Team of IPE Global Limited, India. The team members are: 1. Sanjay Sinha, Team Leader 2. Promila Bishnoi, Evaluation & VfM Expert 3. Gaurav Prateek, Research Manager 4. Manab Chakraborty, Institutional Expert 5. Achin Biyani, Finance Expert 6. Sheena Kapoor, Research Associate Contact Person Dr. Soumen Bagchi, Project Coordinator, [email protected] Copy Right Department for International Development, UK will have the copy right of the field data and information collected, and the evaluation report. Compliance with Ethics Principles IPE Global Limited maintains compliance with the global standards and policies, such as the OECD Standards for Development Evaluation, DFID’s Ethics Principles for Research and Evaluation (2011), and DFID’s zero tolerance stance on corruption and fraud. The corporate values and ethics are safeguarded through a set of policies and codes of conduct including anti-fraud and anti-corruption, conflict of interest, equity, diversity and quality assurance. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this report are those of the evaluation team and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the Department for International Development, UK. Evaluation of impacts of Development Capital Investment Intervention of DFID India’s Private Sector Infrastructure Portfolio Acronyms bn Billion -

Ipe Global Limited, New Delhi the Whistleblower Policy A

IPE GLOBAL LIMITED, NEW DELHI THE WHISTLEBLOWER POLICY A. General IPE Global Limited (IPE Global), New Delhi (hereinafter referred to as “the Company”) seeks to develop and promote a culture in which strong sense of personal responsibility underpins adherence to Corporate Policy. The Company believes in the conduct of the affairs of its constituents in a fair and transparent manner by adopting highest standards of professionalism, honesty, integrity and ethical behaviour. The Company believes in accountability and transparency as a mechanism to enable all staff members to voice concerns internally in a responsible and effective manner when they discover information which they believe shows serious malpractice. B. References This document is intended to provide guidance and should be read in conjunction with: i. The Whistleblowers Protection Act, 2011, Government of India; ii. IPE Global Anti-Fraud and Anti-Corruption Policy; iii. IPE Global Conflict of Interest Policy; iv. IPE Global Employee Code of Conduct; v. IPE Global Policy on Prevention of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse; vi. Other Corporate Policies in relation to investigative guidelines. C. Purpose The Whistleblower Policy (hereinafter referred to as “the Policy”) reinforces the value the Company places on its staff members, to be honest and respected members of their individual professions. It establishes a mechanism to receive bona fide concerns/ disclosure on any allegation of malpractice or to inquire or cause an inquiry into such disclosure and to provide adequate safeguards against victimisation of the person making such disclosure and for matters connected therewith and incidental thereto. D. Scope This policy applies to entire workforce in the Company involving staff members, whatever their status (including those on contract), subcontractors, sub-consultants, and/ or any other parties having business relations with the Company. -

Designation Associate Director – South East

Designation Associate Director – South East Asia Location Manila, Philippines Grade 3A Reporting to Regional Director - South East Asia About IPE IPE Global Limited is an international development consulting group providing expert technical Global assistance and solutions for equitable development and sustainable growth in developing countries. The group’s areas of expertise includes Health, Nutrition and WASH, Urban and Infrastructure Development, Education and Skills Development, Private Sector Development, Environment and Climate Change, Social and Economic Empowerment, Governance, Grant and Fund Management, Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning, and Information Technology & e- Governance. We are ISO 9001:2015 certified, CMMI® Level 3 and ISO 27001:2013 certified company. Over last 18 years, we have successfully implemented over 700 projects in over 100 countries. We have over 800 full time professional staff and over 1000 empanelled consultants working on various projects across the globe. We partner with multilateral & bilateral agencies including ADB, USAID, DFID, World Bank, DANIDA, KfW, EU, etc.; governments; private sector; and philanthropic organisation like BMGF, MasterCard Foundation, etc. We have subsidiaries and offices in UK (IPE Triple Line), Kenya, Ethiopia, India, Bangladesh, and Philippines IPE Global initiated setting up of its liaison office in Manila in the year 2016 and is now in the process of staffing the operations. The main purpose for Manila office is to build relationship with key clients in the region, especially the Asian Development Bank and also focus on the needs and priorities of national and sub-national governments in South East Asia, Central Asia & the Pacific. With presence in Philippines and Myanmar, IPE Global will work to strengthen health systems, revitalise key social and physical infrastructure, strengthen government institutions and provide solutions to improve quality of life, propel economic progress and help alleviate poverty. -

DESIGNATION COMMUNICATION OFFICER LOCATION New Delhi

DESIGNATION COMMUNICATION OFFICER LOCATION New Delhi ABOUT IPE IPE Global Limited (IPE Global) is an international development consultancy group providing expert GLOBAL technical assistance in developing countries. The group partners with multilateral and bilateral agencies, governments, corporates and not-for-profit entities in anchoring development agenda for equitable development and sustainable growth. Headquartered in India with seven international offices in United Kingdom, Kenya, Ethiopia, Myanmar, Nepal, Philippines and Bangladesh, the group offers a range of integrated, innovative and high-quality consulting services across several sectors and practices. The organization has multi-disciplinary team of professionals, bringing together the right skills and technical expertise for enriching lives in poor and developing countries. Our experts work closely with program stakeholders and clients to co-design solutions for complex socio- economic issues. We strive to create enabling environment for path breaking social and policy reforms that contribute to sustainable development. For more details, please visit www.ipeglobal.com JOB DESCRIPTION IPE Global is inviting applications for a contractual position in our Corporate Communications team. The incumbent would be responsible for creating/editing quality content for various communication products, managing/updating global & subsidiary websites and conducting thorough research on industry-related topics, generating ideas for new content types and proofreading the same. The role caters -

Making Development a Ground Reality MISSION and the IPE GLOBAL REACH VISION

Making Development a Ground Reality MISSION AND THE IPE GLOBAL REACH VISION What differentiates us is our collaborative approach to work, with governments and development agencies. 130 million+ People Reached MISSION “To partner with international agencies and governments to provide innovative solutions 1000+ and support to address the global challenges of 800+ Empanelled development” Workforce National & Consultants International VISION 5 “Becoming a cross-sector ‘ideas powerhouse’, International bringing together cutting edge knowledge and Offices 100+ management skills to enable policy reforms for a Countries more inclusive, equitable and sustainable world” Projects 700+ Implemented Projects Delivered 9 National Project Offices WHO WE ARE IPE Global Limited is an international Headquartered in India with four international offices in United Kingdom, Kenya, Ethiopia and Bangladesh, the group offers a range of integrated, development consulting group innovative and high quality consulting services across several sectors and practices. providing expert technical assistance A trusted partner to its clients, IPE Global draws together team of and solutions for equitable economists, chartered accountants, sociologists, public sector experts, educationists, planners, architects, environmentalists, scientists, development and sustainable growth project managers and program managers — all dedicated to finding clear solutions to complex world problems. IPE Global has 800 full time in developing countries. professional staff and over 1000 empanelled consultants working on various projects spread across the globe, in different locations. Over the last 17 years, IPE Global has successfully implemented 700 projects in over 100 countries, across 5 major continents. The group partners with multilateral and bilateral agencies, governments, corporates and not- for-profit entities in anchoring development agenda for sustained and equitable growth. -

Makewayforher

#MakeWayForHer 1 MD SPEAKS SOCIETY THAT FAILS ITS WOMEN AND GIRLS, ULTIMATELY FAILS ITSELF… Women’s social and economic empowerment is critical for gender equality and for achieving the goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Women make up one half of the world’s human capital and yet women continue to be denied control and access to resources and decision making. Gender inequality and skewed distribution of assets and power within family, workplace and socio-political institutions are both the cause and consequence of multiple forms of discrimination that tend to reproduce themselves over time and over generations thus having a negative impact on development outcomes. Empowering and educating girls and women and leveraging their talent and leadership fully in the global economy, politics and society emerges as the fundamental element of prospering in an ever more competitive world. It is time the world treats women differently and especially the workplace… The workplace is where the woman spends the maximum time and colleagues become family. Investing in women is investing in our future. I want to urge women to stand their ground. Fight back. Win. Break free from the shackles that tie them down and chase their dreams. It is time there are more women leaders. And, we as men, owe it to them. Let us together #MakeWayforHer. I pledge to #BeboldforChange and accelerate gender parity. Do you? Best wishes Ashwajit Singh 2 #MakeWayForHer #MakeWayForHer Campaign Do women come with a work expiry? The world of work is changing. The theme for International Women’s Day, 8 March, 2017, focuses on “Women in the Changing World of Work: Planet 50-50 by 2030”. -

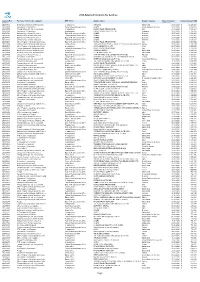

2020 Awarded Contracts for Services Page 1

2020 Awarded Contracts for Services Contract Ref. Purchase Order for the supply of WHO Office Supplier Name Supplier Country Date of Contract Contract Amount USD Number Approval 202511512 Building Construction incl Renovation Headquarters IMPLENIA Switzerland 20.02.2020$ 25,225,723 202563898 Renovation / Construction Eastern Mediterranean Office UNOPS United States of America 10.07.2020$ 9,000,000 202587575 Transportation (air, rail, sea, ground) Headquarters WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Italy 21.09.2020$ 7,468,267 202576069 Renovation / Construction Headquarters CADG ENGINEERING PTE. LTD. Singapore 14.09.2020$ 7,135,155 202561741 Outsourcing of Human Resources Eastern Mediterranean Office UNOPS Denmark 05.07.2020$ 5,654,852 202586965 Outsourcing of Human Resources Eastern Mediterranean Office UNOPS Denmark 18.09.2020$ 5,654,852 202484781 Outsourcing of Human Resources Eastern Mediterranean Office UNOPS Denmark 21.01.2020$ 5,649,432 202538768 Outsourcing of Human Resources Eastern Mediterranean Office UNOPS Denmark 17.04.2020$ 5,649,432 202541083 Other Program related Operating Costs Eastern Mediterranean Office WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Italy 27.04.2020$ 5,207,950 202571690 Outsourcing Consulting & Audit Services Europe Office DOCTORS WORLDWIDE – TURKEY “YERYUZU DOKTORLARI DERNEGI”Turkey 03.08.2020$ 4,594,479 202562137 Other Program related Operating Costs Headquarters CHINA MEHECO CO., LTD. China 06.07.2020$ 4,200,000 202596308 Custom clearance & Warehouse rental Eastern Mediterranean Office WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Italy 14.10.2020$ 4,010,189 202523184 Building Construction incl Renovation Headquarters APLEONA HSG SA Switzerland 06.03.2020$ 4,004,128 202532908 Building Construction incl Renovation Headquarters ITTEN+BRECHBUHL SA Switzerland 27.03.2020$ 3,960,989 202484795 Outsourcing of Human Resources Eastern Mediterranean Office CHIP TRAINING AND CONSULTING (PVT) LTD. -

Designation Associate Director – Central

Designation Associate Director – Central Business Development Location New Delhi, India Reporting to Chief Strategy & Diversification Officer Candidates interested in the position are requested to email their updated CV on How to Apply [email protected] along with name of the position clearly mentioned in the subject line. About IPE IPE Global Limited is an international development consulting group providing expert technical Global assistance and solutions for equitable development and sustainable growth in developing countries. The group’s areas of expertise includes Health, Nutrition and WASH, Urban and Infrastructure Development, Education and Skills Development, Private Sector Development, Environment and Climate Change, Social and Economic Empowerment, Governance, Grant and Fund Management, Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning, and Information Technology & e- Governance. We are ISO 9001:2015 certified, CMMI® Level 3 and ISO 27001:2013 certified company. Over last 18 years, we have successfully implemented over 700 projects in over 100 countries. We have over 800 full time professional staff and over 1000 empanelled consultants working on various projects across the globe. We partner with multilateral & bilateral agencies including ADB, USAID, DFID, World Bank, DANIDA, KfW, EU, etc.; governments; private sector; and philanthropic organisation like BMGF, MasterCard Foundation, etc. We have subsidiaries and offices in UK (IPE Triple Line), Kenya, Ethiopia, India, Bangladesh, Myanmar and Philippines. For more details, please visit www.ipeglobal.com ; www.ipeafrica.com ; www.tripleline.com Job Description IPE Global seeks an experienced professional to serve as Associate Director – Central Business Development for IPE Global New Delhi Office. He/she will have overall responsibility for developing business and supervising the implementation of IPE Global social sector projects in South East Asia, Central Asia & the Pacific in line with IPE Global’s project management protocols. -

Date Designation Assistant Manager – Cities

Date Designation Assistant Manager – Cities, Infrastructure and Growth Location New Delhi, India Employment Type Regular (Regular/Contractual) Grade TBD Reporting to Sk Salim Altaf (Sr. Manager) About Department and Project (if Business Development and Programme Management applicable) Job Responsibilities, IPE Global seeks an experienced professional to serve as Assistant Manager – Business Skills and Development (BD) and Programme Management (PM) for IPE Global Delhi Office. S/he Competencies will work in close coordination with our Central, Sectoral and World-wide Team based out of our India, Africa, Bangladesh, Nepal, UK, Philippines & Myanmar offices and will support the team in the overall business development and project execution. S/he will also play an important role in supporting IPE Global’s wider business growth plans specifically in the urban development sector in India, South East Asia, Nepal, Central Asia & the Pacific. General Responsibility: • Tracking business development opportunities in the allocated sector & closing deals on new business & account management • Supporting in day to day business development & project management function including providing technical inputs to the preparation of proposals and reports • Developing business plans – targeting high potential clients, pitching presentations and developing outreach materials • Networking and liaising with other stakeholders in the sector • Preparing presentations/credentials and presenting IPE Global at various levels • Participating in creative development process, taking briefs and communicating clearly to the team Key Responsibilities Areas: • Co-ordinate and Manage the preparation of EOI/Proposals: o Identification of business opportunities in the sector and region. o Prepare summary and key points of opportunities. o Ensure compliance of proposal as per tender requirements and support on preparation of EoI’s and Proposals o Provide backend support to other teams and IPE Global offices in India, Africa and the UK. -

Making Development a Ground Reality MISSION and VISION What Differentiates Us Is Our Collaborative Approach to Work, with Governments and Development Agencies

Making Development a Ground Reality MISSION AND VISION What differentiates us is our collaborative approach to work, with governments and development agencies. MISSION To partner with international agencies and governments to provide innovative solutions and support to address the global challenges of sustainable development. VISION “Becoming a cross-sector ‘ideas powerhouse’, bringing together cutting edge knowledge and management skills to enable policy reforms for a more inclusive, equitable and sustainable world” THE IPE GLOBAL REACH 300 million+ People Reached 1000+ 800+ Empanelled Workforce National & Consultants International 4 International Offices 100+ Countries Projects 800+ Implemented Projects Delivered 13 National Project Offices WHO WE ARE IPE Global Limited is an international development consulting group providing expert technical assistance and solutions to help developing countries achieve Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), transforming the world for the better. Headquartered in India with four international offices in United Kingdom, Kenya, Ethiopia and Bangladesh, the group offers a range of integrated, innovative and high quality consulting services across several sectors and practices. A trusted partner to its clients, IPE Global draws together a team of economists, chartered accountants, sociologists, public sector experts, educationists, urban planners, architects, environmentalists, scientists, project managers and program managers — all dedicated to finding clear solutions to complex world problems. IPE Global has 800 full time professional staff and over 1000 empanelled consultants working on various projects spread across the globe, in different locations. Over the last 18 years, IPE Global has successfully implemented more than 800 projects in over 100 countries, across 5 major continents. The group partners with multilateral and bilateral agencies, governments, corporates and not-for-profit entities in anchoring development agenda for sustained and equitable growth.