A Muslim Woman's Right to a Khulʿ in Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan

Politics of Exclusion: Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan by Sadia Saeed A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor George P. Steinmetz, Chair Professor Howard A. Kimeldorf Associate Professor Fatma Muge Gocek Associate Professor Genevieve Zubrzycki Professor Mamadou Diouf, Columbia University © Sadia Saeed 2010 2 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my parents with my deepest love, respect and gratitude for the innumerable ways they have supported my work and choices. ii Acknowledgements I would like to begin by acknowledging the immense support my parents have given me every step of the way during my (near) decade in graduate school. I have dedicated this dissertation to them. My ammi and baba have always believed in my capabilities to accomplish not only this dissertation but much more in life and their words of love and encouragement have continuously given me the strength and the will to give my research my very best. My father‘s great enthusiasm for this project, his intellectual input and his practical help and advice during the fieldwork of this project have been formative to this project. I would like to thank my dissertation advisor George Steinmetz for the many engaged conversations about theory and methods, for always pushing me to take my work to the next level and above all for teaching me to recognize and avoid sloppiness, caricatures and short-cuts. It is to him that I owe my greatest intellectual debt. -

IN the SUPREME COURT of PAKISTAN (Appellate Jurisdiction)

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN (Appellate Jurisdiction) Present: Mr. Justice Manzoor Ahmad Malik Mr. Justice Syed Mansoor Ali Shah C.P.1290-L/2019 (Against the Order of Lahore High Court, Lahore dated 31.01.2019, passed in W.P. No. 5898/2019) D. G. Khan Cement Company Ltd. ...….Petitioner(s) Versus Government of Punjab through its Chief Secretary, Lahore, etc. …….Respondent(s) For the petitioner(s): Mr. Salman Aslam Butt, ASC. For the respondent(s): Ms. Aliya Ejaz, Asstt. A.G. Dr. Khurram Shahzad, D.G. EPA. M. Nawaz Manik, Director Law, EPA. M. Younas Zahid, Dy. Director. Fawad Ali, Dy. Director, EPA (Chakwal). Kashid Sajjan, Asstt. Legal, EPA. Rizwan Saqib Bajwa, Manager GTS. Research Assistance: Hasan Riaz, Civil Judge-cum-Research Officer at SCRC.1 Date of hearing: 11.02.2021 JUDGEMENT Syed Mansoor Ali Shah, J.- The case stems from Notification dated 08.03.2018 (“Notification”) issued by the Industries, Commerce and Investment Department, Government of the Punjab (“Government”), under sections 3 and 11 of the Punjab Industries (Control on Establishment and Enlargement) Ordinance, 1963 (“Ordinance”), introducing amendments in Notification dated 17.09.2002 to the effect that establishment of new cement plants, and enlargement and expansion of existing cement plants shall not be allowed in the “Negative Area” falling within the Districts Chakwal and Khushab. 2. The petitioner owns and runs a cement manufacturing plant in Kahoon Valley in the Salt Range at Khairpur, District Chakwal and feels wronged of the Notification for the reasons, -

Emergence of Women's Organizations and the Resistance Movement In

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 19 | Issue 6 Article 9 Aug-2018 Defying Marginalization: Emergence of Women’s Organizations and the Resistance Movement in Pakistan: A Historical Overview Rahat Imran Imran Munir Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Imran, Rahat and Munir, Imran (2018). Defying Marginalization: Emergence of Women’s Organizations and the Resistance Movement in Pakistan: A Historical Overview. Journal of International Women's Studies, 19(6), 132-156. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol19/iss6/9 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2018 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Defying Marginalization: Emergence of Women’s Organizations and the Resistance Movement in Pakistan: A Historical Overview By Rahat Imran1 and Imran Munir2 Abstract In the wake of Pakistani dictator General-Zia-ul-Haq’s Islamization process (1977-1988), the country experienced an unprecedented tilt towards religious fundamentalism. This initiated judicial transformations that brought in rigid Islamic Sharia laws that impacted women’s freedoms and participation in the public sphere, and gender-specific curbs and policies on the pretext of implementing a religious identity. This suffocating environment that eroded women’s rights in particular through a recourse to politicization of religion also saw the emergence of equally strong resistance, particularly by women who, for the first time in Pakistan’s history, grouped and mobilized an organized activist women’s movement to challenge Zia’s oppressive laws and authoritarian regime. -

Chapter 6 the Creation of Shariat Courts518

CHAPTER 6 THE CREATION OF SHARIAT COURTS518 Zia-ul-Haq used his unfettered powers as a military dictator to initiate a radical programme of Islamisation.519 As mentioned in the Introduction, the most visible and internationally noticed aspect of this programme was a set of Ordinances which introduced Islamic criminal law for a number of offences.520 The effect of these measures is considered controversial. On one side of the spectrum is Kennedy, who in two articles argued that the Hudood Ordinances did not have a detrimental effect on the legal status of women.521 This claim has been refuted by a number of academics and human rights activists.522 In 1988, Justice Javaid Iqbal, while serving as a Supreme Court judge, stated in an article that: Ironically, those provisions of the law which were designed to protect women, now provide the means for convicting them for Zina. As a result of this inconsistency in the law, eight out of every ten women in jails today are those charged with the offence of Zina and no legal aid is available to them.523 Irrespective of any particular quantitative evaluation of the new Islamic criminal laws, there can be no doubt that there has been and still is an intense and informed 518 The expression shariat courts denotes all those courts which are constitutionally empowered to declare laws repugnant to Islam. They comprise the shariat benches of the High Courts and their successors, i.e. the Federal Shariat Court and the Shariat Appellate Bench of the Supreme Court. 519 For a good overview of Zias reign, see Mushaid Hussain, The Zia Years, Lahore, 1990 and Ayesha Jalal, The State of Martial Law: The Origins of Pakistans Political Economy of Defence, Cambridge, 1990. -

World Bank Document

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT (EA) AND THE ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK Public Disclosure Authorized PUNJAB EDUCATION SECTOR REFORMS PROGRAM-II (PESRP-II) Public Disclosure Authorized PROGRAM DIRECTOR PUNJAB EDUCATION SECTOR REFORMS PROGRAM (PESRP) SCHOOL EDUCATION DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB Tel: +92 42 923 2289~95 Fax: +92 42 923 2290 url: http://pesrp.punjab.gov.pk email: [email protected] Public Disclosure Authorized Revised and Updated for PERSP-II February 2012 Public Disclosure Authorized DISCLAIMER This environmental and social assessment report of the activities of the Punjab Education Sector Reforms Program of the Government of the Punjab, which were considered to impact the environment, has been prepared in compliance to the Environmental laws of Pakistan and in conformity to the Operational Policy Guidelines of the World Bank. The report is Program specific and of limited liability and applicability only to the extent of the physical activities under the PESRP. All rights are reserved with the study proponent (the Program Director, PMIU, PESRP) and the environmental consultant (Environs, Lahore). No part of this report can be reproduced, copied, published, transcribed in any manner, or cited in a context different from the purpose for which it has been prepared, except with prior permission of the Program Director, PESRP. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This document presents the environmental and social assessment report of the various activities under the Second Punjab Education Sector Reforms Program (PESRP-II) – an initiative of Government of the Punjab for continuing holistic reforms in the education sector aimed at improving the overall condition of education and the sector’s service delivery. -

APPOINTMENT and CONDITIONS of SERVICE) REGULATIONS, 2016 AIM: to Enforce the MDA (Appointment and Conditions of Service) Regulations 2016

DIRECTORATE OF FINANCE AND ADMINISTRATION ADMIN BRANCH AGENDA NO. 01 MDA (APPOINTMENT AND CONDITIONS OF SERVICE) REGULATIONS, 2016 AIM: To enforce the MDA (Appointment and Conditions of Service) Regulations 2016. DETAILS/ EXISTING ARRANGEMENTS: 2. MDA (Appointments and Conditions of Service) Regulations, 1980 has remained enforced and are still under implementation since 1980. Over the period of 36 years, 68 meetings of Governing Body have been held and time to time various amendments have been made in the said Regulations and its schedule. If seen critically, the current schedule of Regulations is full of amendments, tailored promotion channels and abolished posts which were otherwise necessary for smooth functioning of MDA. 3. Across the board, it has been observed that promotion criteria for various posts have been shifted from seniority-cum-fitness basis to mandatory trainings and departmental training examination. Recently the instructions of Government of the Punjab for ensuring merit based promotions basing on mandatory training/promotion exam has been received, which is also being placed for adoption by MDA. The same has also been proposed for almost all the posts whether technical or general cadre so that merit based promotions may be ensured. 4. The regulations include two parts namely appointment and the condition of service for MDA employees and its Schedule. Extensive efforts have been put in for making this schedule practicable. An effort has been made that no post may remain stagnant and mostly post has been given promotion prospects. The same did not exist in the current Schedule. There were many discrepancies as already mentioned above which have also been rectified. -

Protecting Women: an Examination of the Deficiencies in the Protection of Women Act and Other Qualitative Barriers

Protecting Women: An Examination of the Deficiencies in the Protection of Women Act and Other Qualitative Barriers By Saima Akbar Master of Public Administration, University of Victoria, 2007 Bachelor of Arts in Political Science, University of Victoria, 2003 PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY SPECIAL ARRANGEMENTS IN THE FACULTY ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES In the School for International Studies © Saima Akbar 2008 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2008 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: SaimaAkbar Degree: Master ofArts in International Studies Title of Protecting Women: An Examination of the Deficiencies Research Project: in the Protection of Women Act and Other Qualitative Barriers Supervisory Committee: Chair: Dr. John Harriss Professor of International Studies Dr. Tamir Moustafa Senior Supervisor Associate Professor of International Studies Dr. Lara Nettelfield Supervisor Assistant Professor of International Studies Date Approved: ii SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, -

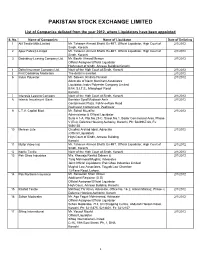

List of Liquidators

PAKISTAN STOCK EXCHANGE LIMITED List of Companies delisted from the year 2012, where Liquidators have been appointed S. No. Name of Companies Name of Liquidator Date of Delisting 1 Alif Textile Mills Limited Mr. Tahseen Ahmed Bhatti, Ex-MIT, Official Liquidator, High Court of 2/1/2012 Sindh, Karachi 2 Apex Fabrics Limited Mr. Tahseen Ahmed Bhatti, Ex-MIT, Official Liquidator, High Court of 2/1/2012 Sindh, Karachi 3 Dadabhoy Leasing Company Ltd. Mr. Bashir Ahmed Memon 2/1/2012 Official Assignee/Official Liquidator High Court of Sindh, Annexe Building,Karachi. 4 Delta Insurance Company Ltd. Nazir of the High Court of Sindh, Karachi 2/1/2012 5 First Dadabhoy Modaraba The detail is awaited. 2/1/2012 6 Indus Polyester Mr. Saleem Ghulam Hussain 2/1/2012 Advocate of Navin Merchant Associates Liquidator: Indus Polyester Company Limited B/54, S.I.T.E., Manghopir Road Karachi 7 Interasia Leasing Company Nazir of the High Court of Sindh, Karachi 2/1/2012 8 Islamic Investment Bank Barrister Syed Mudassir Amir 2/1/2012 Containment Plaza, Fakhr-e-Alam Road Peshawar Cantonment, Peshawar 9 L.T.V. Capital Mod. Mr. Sohail Muzaffar 2/1/2012 Administrator & Official Liquidator Suite # 1-A, Plot No.25-C, Street No.1, Badar Commercial Area, Phase- V (Ext), Defence Housing Authority, Karachi, Ph: 5843967-68, Fx: 5856135 10 Mehran Jute Chudhry Arshad Iqbal, Advocate 2/1/2012 (Official Liquidator) High Court of Sindh, Annexe Building Karachi. 11 Myfip Video Ind. Mr. Tahseen Ahmed Bhatti, Ex-MIT, Official Liquidator, High Court of 2/1/2012 Sindh, Karachi 12 Norrie Textile Nazir of the High Court of Sindh, Karachi 2/1/2012 13 Pak Ghee Industries M/s. -

Ahle Hadith – Honour Killings – PML (Q) – Political Violence – Exit Procedures

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: PAK34931 Country: Pakistan Date: 29 May 2009 Keywords: Pakistan – Ahl-I Hadith – Ahle Hadith – Honour killings – PML (Q) – Political violence – Exit procedures This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide basic information on Ahle Hadith (or Ahl-I Hadith) and whether it is known to be in conflict with other Muslim groups. 2. Please provide information on honour killing in Pakistan, and whether it is particular individuals or groups that are most at risk or are most associated with its practice. 3. Following the 2008 elections there were reports that members of the PML(Q) were subject to harassment. Please provide an update on PML(Q) activities and whether this is still correct. 4. Would a person have been able to leave Pakistan in 2008 if they were of interest to the authorities? RESPONSE 1. Please provide basic information on Ahle Hadith (or Ahl-I Hadith) and whether it is known to be in conflict with other Muslim groups. Ahl-i-Hadith or Ahle Hadith is said to be a Sunni sub-sect of Wahhabi inspiration, and to have originated in the nineteenth century as a religious educational movement. -

Syed Mansoor Ali Shah, J

Stereo. H C J D A 38. Judgment Sheet IN THE LAHORE HIGH COURT LAHORE JUDICIAL DEPARTMENT Case No: W.P. 5406/2011 Syed Riaz Ali Zaidi Versus Government of the Punjab, etc. JUDGMENT Dates of hearing: 20.01.2015, 21.01.2015, 09.02.2015 and 10.02.2015 Petitioner by: Mian Bilal Bashir assisted by Raja Tasawer Iqbal, Advocates for the petitioner. Respondents by: Mian Tariq Ahmed, Deputy Attorney General for Pakistan. Mr. Muhammad Hanif Khatana, Advocate General, Punjab. Mr. Anwaar Hussain, Assistant Advocate General, Punjab. Tariq Mirza, Deputy Secretary, Finance Department, Government of the Punjab, Lahore. Nadeem Riaz Malik, Section Officer, Finance Department, Government of the Punjab, Lahore. Amici Curiae: M/s Tanvir Ali Agha, former Auditor General of Pakistan and Waqqas Ahmad Mir, Advocate. Assisted by: M/s. Qaisar Abbas and Mohsin Mumtaz, Civil Judges/Research Officers, Lahore High Court Research Centre (LHCRC). “The judiciary should not be left in a position of seeking financial and administrative sanctions for either the provision of infrastructure, staff and facilities for the judges from the Executive and the State, which happens W.P. No.5406/2011 2 to be one of the largest litigants….autonomy is required for an independent and vibrant judiciary, to strengthen and improve the justice delivery system, for enforcing the rule of law1.” Syed Mansoor Ali Shah, J:- This case explores the constitutionalism of financial autonomy and budgetary independence of the superior judiciary on the touchstone of the ageless constitutional values of independence of judiciary and separation of powers. 2. Additional Registrar of this High Court has knocked at the constitutional jurisdiction of this Court, raising the question of non-compliance of the executive authority of the Federation by the Provincial Government, as the direction of the Prime Minister to the Provincial Government to enhance the allowances of the staff of the superior judiciary goes unheeded. -

The Crime of Rape and the Hanafi Doctrine of Siyasah

Pakistan Journal of Criminology Volume 6, No.1, Jan-June 2014, pp.171 - 202 171 The Crime of Rape and The Hanafi Doctrine of Siyasah Muhammad Mushtaq Ahmad Abstract The issue of rape has remained one of the most contentious issues in the modern debate on Islamic criminal law. It is generally held that because of the strict criterion for proving this offence,injustice is done with the victim of rape. This essay examines this issue in detail and shows that the doctrine of siyasah [the authority of the government for administration of justice] in the Hanafi criminal law can make the law against sexual violence more effective without altering the law of hudud. The basic contention of this essay is that a proper understanding of the Hanafi criminal law, particularly the doctrine of siyasah, can give viable and effective solutions to this complicated issue of the Pakistani criminal justice system. It recommends that an offence of sexual violence is created which does not involve sexual intercourse as an essential element. That is the only way to delink this offence from zina and qadhf and bring it under the doctrine of siyasah. This offence will, thus, become sub-category of violence, not zina. The government may bring sex crimes involving the threat or use of violence under one heading and, then, further categorize it in view of the intensity and gravity of the crime. It may also prescribe proper punishments for various categories of the crime. Being a siyasah crime, it will not require the standard proof prescribed by Islamic law for the hadd offences. -

Lahore High Court Lahore

Stereo. H C J D A 38. Judgment Sheet IN THE LAHORE HIGH COURT LAHORE JUDICIAL DEPARTMENT Case No: W. P. No.115949/2017 Maple Leaf Cement Factory Versus Environmental Protection Ltd. Agency, etc. JUDGMENT Date of hearing: 21.12.2017 Petitioner by: M/s. Mansoor Usman Awan, Shazeen Abdullah and Hussain Ibrahim, Advocates. Respondent (s) M/s Asma Hamid and Anwaar Hussain, by: Additional Advocates General, Punjab. Mr. Arshad Mehmood, Secretary, Mines and Mineral, Government of the Punjab. Mr. Zafar Javaid, Director, Mines and Mineral, Government of the Punjab. Mr. Muhammad Javaid, Superintendent, Mines and Mineral, Government of the Punjab. Mian Ejaz Majeed, Deputy Director (L&E), EPA. Mr. Asim Rehman, Deputy Director (EIA), EPA. The fate of the Creation is the fate of the humanity. - E.O.Wilson1 Syed Mansoor Ali Shah, C.J:- Facts: Brief facts, as argued by the learned counsel for the petitioner, are that the cement plant of the petitioner was set up in the year 1956 by the West Pakistan Industrial Development Corporation with the 1 The Creation - An appeal to save life on Earth – by E.O.Wilson P.14 W.P. No.115949/2017 2 production capacity of 3000 tonnes per annum. The cement plant was privatized in the year 1992 when the petitioner company purchased the same. The production capacity of the plant at that time of the purchase of the plant by the petitioner was 4000 tonnes per annum. Later on the production capacity of the cement plant was enhanced by the petitioner and Line-II of the plant was added in the year 2007 with an additional production capacity of 7,000 tonnes per annum.