S.M.C. 8 2018.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IN the SUPREME COURT of PAKISTAN (Appellate Jurisdiction)

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN (Appellate Jurisdiction) Present: Mr. Justice Manzoor Ahmad Malik Mr. Justice Syed Mansoor Ali Shah C.P.1290-L/2019 (Against the Order of Lahore High Court, Lahore dated 31.01.2019, passed in W.P. No. 5898/2019) D. G. Khan Cement Company Ltd. ...….Petitioner(s) Versus Government of Punjab through its Chief Secretary, Lahore, etc. …….Respondent(s) For the petitioner(s): Mr. Salman Aslam Butt, ASC. For the respondent(s): Ms. Aliya Ejaz, Asstt. A.G. Dr. Khurram Shahzad, D.G. EPA. M. Nawaz Manik, Director Law, EPA. M. Younas Zahid, Dy. Director. Fawad Ali, Dy. Director, EPA (Chakwal). Kashid Sajjan, Asstt. Legal, EPA. Rizwan Saqib Bajwa, Manager GTS. Research Assistance: Hasan Riaz, Civil Judge-cum-Research Officer at SCRC.1 Date of hearing: 11.02.2021 JUDGEMENT Syed Mansoor Ali Shah, J.- The case stems from Notification dated 08.03.2018 (“Notification”) issued by the Industries, Commerce and Investment Department, Government of the Punjab (“Government”), under sections 3 and 11 of the Punjab Industries (Control on Establishment and Enlargement) Ordinance, 1963 (“Ordinance”), introducing amendments in Notification dated 17.09.2002 to the effect that establishment of new cement plants, and enlargement and expansion of existing cement plants shall not be allowed in the “Negative Area” falling within the Districts Chakwal and Khushab. 2. The petitioner owns and runs a cement manufacturing plant in Kahoon Valley in the Salt Range at Khairpur, District Chakwal and feels wronged of the Notification for the reasons, -

Federal Judicial Academy Bulletin

FEDERAL JUDICIAL ACADEMY BULLETIN January - March, 2014 Mr. Parvaiz Ali Chawla, Director General, Federal Judicial Academy presenting souvenir to Hon’ble Mr. Justice Mian Saqib Nisar , Judge , Supreme Court of Pakistan Contents Hon'ble Mr. Justice Mushir Alam reiterates importance 01 of judicial training DG, FJA asks members of district judiciary to achieve 02 excellence in administration of justice Hon'ble Mr. Justice Anwar Zaheer Jamali asks 04 Superintendents of District and Sessions Courts to institutionalize their practical knowledge Superintendents of District and Sessions Courts 06 advised to work with honesty, devotion and diligence Hon'ble Mr. Justice Mian Saqib Nisar Improvement is always required to enhance 08 capacities: Hon'ble Chief Justice, Islamabad High Court Hon'ble Mr. Justice Mian Saqib Nisar urges judges, 09 lawyers to attain command on law Rule of law creates order, harmony in society 10 Hon'ble Mr. Justice Ejaz Afzal Khan Hon'ble Mr. Justice Amir Hani Muslim asks young 12 judges about effective time management Hon'ble Mr. Justice Ijaz Ahmed Chaudhry asks 13 Editorial Board Family Court Judges to save estranged families from break up Patron-in-Chief Family Court Judges asked for speedy settlement of 15 family disputes: Hon'ble Mr. Justice Riaz Ahmad Khan Hon'ble Mr. Justice Tassaduq Hussain Jillani Enrich knowledge of law, interpret, apply and 16 implement it with highest degree of accuracy Chief Justice of Pakistan/Chairman BoG Hon'ble Mr. Justice Dost Muhammad Khan Editor-in-Chief Judges can play their role to reform 18 society: Hon'ble Mr. Justice Ejaz Afzal Khan Parvaiz Ali Chawla Director General Hon'ble Mr. -

World Bank Document

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT (EA) AND THE ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK Public Disclosure Authorized PUNJAB EDUCATION SECTOR REFORMS PROGRAM-II (PESRP-II) Public Disclosure Authorized PROGRAM DIRECTOR PUNJAB EDUCATION SECTOR REFORMS PROGRAM (PESRP) SCHOOL EDUCATION DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB Tel: +92 42 923 2289~95 Fax: +92 42 923 2290 url: http://pesrp.punjab.gov.pk email: [email protected] Public Disclosure Authorized Revised and Updated for PERSP-II February 2012 Public Disclosure Authorized DISCLAIMER This environmental and social assessment report of the activities of the Punjab Education Sector Reforms Program of the Government of the Punjab, which were considered to impact the environment, has been prepared in compliance to the Environmental laws of Pakistan and in conformity to the Operational Policy Guidelines of the World Bank. The report is Program specific and of limited liability and applicability only to the extent of the physical activities under the PESRP. All rights are reserved with the study proponent (the Program Director, PMIU, PESRP) and the environmental consultant (Environs, Lahore). No part of this report can be reproduced, copied, published, transcribed in any manner, or cited in a context different from the purpose for which it has been prepared, except with prior permission of the Program Director, PESRP. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This document presents the environmental and social assessment report of the various activities under the Second Punjab Education Sector Reforms Program (PESRP-II) – an initiative of Government of the Punjab for continuing holistic reforms in the education sector aimed at improving the overall condition of education and the sector’s service delivery. -

3 Who Is Who and What Is What

3 e who is who and what is what Ever Success - General Knowledge 4 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Ever Success Revised and Updated GENERAL KNOWLEDGE Who is who? What is what? CSS, PCS, PMS, FPSC, ISSB Police, Banks, Wapda, Entry Tests and for all Competitive Exames and Interviews World Pakistan Science English Computer Geography Islamic Studies Subjectives + Objectives etc. Abbreviations Current Affair Sports + Games Ever Success - General Knowledge 5 Saad Book Bank, Lahore © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this book may be reproduced In any form, by photostate, electronic or mechanical, or any other means without the written permission of author and publisher. Composed By Muhammad Tahsin Ever Success - General Knowledge 6 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Dedicated To ME Ever Success - General Knowledge 7 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Ever Success - General Knowledge 8 Saad Book Bank, Lahore P R E F A C E I offer my services for designing this strategy of success. The material is evidence of my claim, which I had collected from various resources. I have written this book with an aim in my mind. I am sure this book will prove to be an invaluable asset for learners. I have tried my best to include all those topics which are important for all competitive exams and interviews. No book can be claimed as prefect except Holy Quran. So if you found any shortcoming or mistake, you should inform me, according to your suggestions, improvements will be made in next edition. The author would like to thank all readers and who gave me their valuable suggestions for the completion of this book. -

ROLE of JUDICIARY and JURISPRUDENCE in DOMESTIC and INTERNATIONAL ARBITRATION* by Justice Jawad Hassan**

ROLE OF JUDICIARY AND JURISPRUDENCE IN DOMESTIC AND INTERNATIONAL ARBITRATION* by Justice Jawad Hassan** Introduction Today I will discuss an aspect of arbitration and its impact in Pakistan. Courts in different national systems throughout the world vary with respect to how interventionist they are in the arbitral process. In recent decades, ever since Pakistan has entered the new world of international trade, the role of judiciary in the matter of arbitration has gradually been the subject of much debate, as a result of a number of various decisions given by the courts. Is the role that has been played by the judiciary justified? I must confess that my perspective and vision being a counsel in number of international arbitrations (pre, during and post arbitration) has totally changed since my elevation to the Bench. There is a very interesting observation in paragraph 7.01 of Redfern and Hunter on International Arbitration: Sixth Edition: Oxford University Press. The observation is as follows:- “The relationship between national courts and arbitral tribunals swings between forced cohabitation and true partnership.” We shall now look into various arbitration decisions passed by the Pakistani Courts, then venture into the challenges faced by the legal fraternity of Pakistan in arbitration, followed by the need for judicial training and other ancillary matters before concluding this paper. Role of Pakistan and the International Arbitration since 2005 After ratifying the New York Convention, Pakistan first brought the Recognition and Enforcement (Arbitration Agreements and Foreign Arbitral Awards) Ordinance, 2005 (“2005 Ordinance”) which was eventually promulgated as an Act in 2011 called the Recognition and Enforcement (Arbitration Agreements and Foreign Arbitral Awards) Act, 2011 (the “2011 Act”). -

APPOINTMENT and CONDITIONS of SERVICE) REGULATIONS, 2016 AIM: to Enforce the MDA (Appointment and Conditions of Service) Regulations 2016

DIRECTORATE OF FINANCE AND ADMINISTRATION ADMIN BRANCH AGENDA NO. 01 MDA (APPOINTMENT AND CONDITIONS OF SERVICE) REGULATIONS, 2016 AIM: To enforce the MDA (Appointment and Conditions of Service) Regulations 2016. DETAILS/ EXISTING ARRANGEMENTS: 2. MDA (Appointments and Conditions of Service) Regulations, 1980 has remained enforced and are still under implementation since 1980. Over the period of 36 years, 68 meetings of Governing Body have been held and time to time various amendments have been made in the said Regulations and its schedule. If seen critically, the current schedule of Regulations is full of amendments, tailored promotion channels and abolished posts which were otherwise necessary for smooth functioning of MDA. 3. Across the board, it has been observed that promotion criteria for various posts have been shifted from seniority-cum-fitness basis to mandatory trainings and departmental training examination. Recently the instructions of Government of the Punjab for ensuring merit based promotions basing on mandatory training/promotion exam has been received, which is also being placed for adoption by MDA. The same has also been proposed for almost all the posts whether technical or general cadre so that merit based promotions may be ensured. 4. The regulations include two parts namely appointment and the condition of service for MDA employees and its Schedule. Extensive efforts have been put in for making this schedule practicable. An effort has been made that no post may remain stagnant and mostly post has been given promotion prospects. The same did not exist in the current Schedule. There were many discrepancies as already mentioned above which have also been rectified. -

PLD 2014 Supreme Court 753 Present

P L D 2014 Supreme Court 753 Present: Mian Saqib Nisar, sif Saeed Khan Khosa and Sh. Azmat Saeed, JJ MUHAMMAD ALI---Petitioner Versus ADDITIONAL I.G., FAISALABAD nd others---Respondents Criminal Petition No.478-L of 2014, decided on 16th July, 2014. (Against the order dated 27-3-2014 passed by the Lahore High Court, Lahore in Criminal Miscellaneous No.2404-M of 21009) (a) Criminal Procedure Code (V of 1898)--- ----Ss. 22-A(6) & 561-A---Order passed by Justice of Peace under S.22-A(6), Cr.P.C. impugned before the High Court by way of a petition under S.561-A, Cr.P.C.---Competency /Maintainability---Order passed by the ex officio Justice of the Peace under S.22-A(6), Cr.P.C. was an executive/administrative order---Petition filed before the High Court under S.561-A, Cr.P.C. impugning such order of Justice of Peace was not competent or maintainable---Provisions of S.561-A, Cr.P.C. had relevance only to judicial proceedings and actions and not to any executive or administrative action or function---Jurisdiction of High Court under S. 561-A, Cr.P.C. could be exercised only in respect of orders or proceedings of a court---Phrovisions of S.561-A, Cr.P.C. had no application vis-à-vis executive or administrative orders or proceedings of any non-judicial forum or authority. Khizer Hayat and others v. Inspector-General of Police (Punjab), Lahore and others PLD 2005 Lah. 470; Emperor v. Khwaja Nazir Ahmed AIR (32) 1945 PC 18; Shahnaz Begum v. -

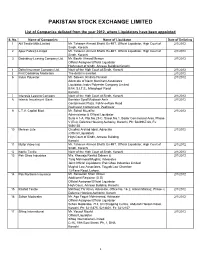

List of Liquidators

PAKISTAN STOCK EXCHANGE LIMITED List of Companies delisted from the year 2012, where Liquidators have been appointed S. No. Name of Companies Name of Liquidator Date of Delisting 1 Alif Textile Mills Limited Mr. Tahseen Ahmed Bhatti, Ex-MIT, Official Liquidator, High Court of 2/1/2012 Sindh, Karachi 2 Apex Fabrics Limited Mr. Tahseen Ahmed Bhatti, Ex-MIT, Official Liquidator, High Court of 2/1/2012 Sindh, Karachi 3 Dadabhoy Leasing Company Ltd. Mr. Bashir Ahmed Memon 2/1/2012 Official Assignee/Official Liquidator High Court of Sindh, Annexe Building,Karachi. 4 Delta Insurance Company Ltd. Nazir of the High Court of Sindh, Karachi 2/1/2012 5 First Dadabhoy Modaraba The detail is awaited. 2/1/2012 6 Indus Polyester Mr. Saleem Ghulam Hussain 2/1/2012 Advocate of Navin Merchant Associates Liquidator: Indus Polyester Company Limited B/54, S.I.T.E., Manghopir Road Karachi 7 Interasia Leasing Company Nazir of the High Court of Sindh, Karachi 2/1/2012 8 Islamic Investment Bank Barrister Syed Mudassir Amir 2/1/2012 Containment Plaza, Fakhr-e-Alam Road Peshawar Cantonment, Peshawar 9 L.T.V. Capital Mod. Mr. Sohail Muzaffar 2/1/2012 Administrator & Official Liquidator Suite # 1-A, Plot No.25-C, Street No.1, Badar Commercial Area, Phase- V (Ext), Defence Housing Authority, Karachi, Ph: 5843967-68, Fx: 5856135 10 Mehran Jute Chudhry Arshad Iqbal, Advocate 2/1/2012 (Official Liquidator) High Court of Sindh, Annexe Building Karachi. 11 Myfip Video Ind. Mr. Tahseen Ahmed Bhatti, Ex-MIT, Official Liquidator, High Court of 2/1/2012 Sindh, Karachi 12 Norrie Textile Nazir of the High Court of Sindh, Karachi 2/1/2012 13 Pak Ghee Industries M/s. -

SUPREME COURT of PAKISTAN, ISLAMABAD FINAL CAUSE LIST 13 of 2018 from 26-Mar to 30-Mar-2018 for Fixation and Result of Cases, Please Visit

SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN, ISLAMABAD FINAL CAUSE LIST 13 of 2018 From 26-Mar to 30-Mar-2018 For fixation and result of cases, please visit www.supremecourt.gov.pk The following cases are fixed for hearing before the Court at Islamabad during the week commencing 26-Mar-2018 at 09:00 AM or soon thereafter as may be convenient to the Court. (i) No application for adjournment through fax/email will be placed before the Court. If any counsel is unable to appear for any reason, the Advocate-on-Record will be required to argue the case. (ii) No adjournment on any ground will be granted. BENCH - I MR. JUSTICE MIAN SAQIB NISAR, HCJ MR. JUSTICE UMAR ATA BANDIAL MR. JUSTICE IJAZ UL AHSAN Monday, 26-Mar-2018 1 C.A.1178/2008 Haji Baz Muhammad and another v. Noor Mr. Abdus Salim Ansari, AOR (Qta) (Specific Performance) Ali and another (Enrl#229) (D.B.) Mr. Kamran Murtaza, ASC (Qta) (Enrl#2333) Mr. Rizwan Ejaz, ASC (Enrl#4107) (Qta) R Ex-Parte Mr. Ahmed Nawaz Chaudhry, AOR (Enrl#243) Mr. Zulfikar Khalid Maluka, ASC (Ibd) (Enrl#2752) 2 C.A.182-P/2013 Muhammad Fateh Khan & others v. Land Mr. Tasleem Hussain, AOR (Pesh) (Land Acquisition) Acquisition Collector Swabi Scarp, (Enrl#187) (S.J.) WAPDA Mardan & others Muhammad Asif Khan, ASC Mir Adam Khan, AOR (Enrl#185) (Pesh) Mr. Mahmudul Islam, AOR (Lhr) (Enrl#177) Mr. Aurangzeb Mirza, ASC (Lhr) (Enrl#2706) and(2) C.A.194-P/2013 Nawabzada Mohammad Usman Khan v. Mr. Muhammad Ajmal Khan, AOR (Pesh) (Land Acquisition) Land Acquisition Collector Swabi Scarp, (Enrl#225) (S.J.) Mardan & others Mr. -

Syed Mansoor Ali Shah, J

Stereo. H C J D A 38. Judgment Sheet IN THE LAHORE HIGH COURT LAHORE JUDICIAL DEPARTMENT Case No: W.P. 5406/2011 Syed Riaz Ali Zaidi Versus Government of the Punjab, etc. JUDGMENT Dates of hearing: 20.01.2015, 21.01.2015, 09.02.2015 and 10.02.2015 Petitioner by: Mian Bilal Bashir assisted by Raja Tasawer Iqbal, Advocates for the petitioner. Respondents by: Mian Tariq Ahmed, Deputy Attorney General for Pakistan. Mr. Muhammad Hanif Khatana, Advocate General, Punjab. Mr. Anwaar Hussain, Assistant Advocate General, Punjab. Tariq Mirza, Deputy Secretary, Finance Department, Government of the Punjab, Lahore. Nadeem Riaz Malik, Section Officer, Finance Department, Government of the Punjab, Lahore. Amici Curiae: M/s Tanvir Ali Agha, former Auditor General of Pakistan and Waqqas Ahmad Mir, Advocate. Assisted by: M/s. Qaisar Abbas and Mohsin Mumtaz, Civil Judges/Research Officers, Lahore High Court Research Centre (LHCRC). “The judiciary should not be left in a position of seeking financial and administrative sanctions for either the provision of infrastructure, staff and facilities for the judges from the Executive and the State, which happens W.P. No.5406/2011 2 to be one of the largest litigants….autonomy is required for an independent and vibrant judiciary, to strengthen and improve the justice delivery system, for enforcing the rule of law1.” Syed Mansoor Ali Shah, J:- This case explores the constitutionalism of financial autonomy and budgetary independence of the superior judiciary on the touchstone of the ageless constitutional values of independence of judiciary and separation of powers. 2. Additional Registrar of this High Court has knocked at the constitutional jurisdiction of this Court, raising the question of non-compliance of the executive authority of the Federation by the Provincial Government, as the direction of the Prime Minister to the Provincial Government to enhance the allowances of the staff of the superior judiciary goes unheeded. -

In the Supreme Court of Pakistan (Original Jurisdiction)

WWW.LIVELAW.IN IN THE SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN (ORIGINAL JURISDICTION) PRESENT: MR. JUSTICE MIAN SAQIB NISAR, HCJ MR. JUSTICE SH. AZMAT SAEED MR. JUSTICE UMAR ATA BANDIAL MR. JUSTICE FAISAL ARAB MR. JUSTICE IJAZ UL AHSAN MR. JUSTICE SAJJAD ALI SHAH MR. JUSTICE MUNIB AKHTAR CONST. PETITIONS NO.50/2018, 51/2018 & 63/2011, CIVIL MISC. APPLICATIONS NO.4922, 5382/2011, 695/2012 & 724/2017 IN CONST. PETITION NO.63/2011, CONST. PETITIONS NO.6/2012, 16/2015 & 20/2015, CIVIL MISC. APPLICATION NO.6966/2017 IN CONST. PETITION NO. 20/2015, CONST. PETITION NO.3/2016, CIVIL MISC. APPLICATION NO.6800/2017 IN CONST. PETITION NO.3/2016, CONST. PETITION NO.13/2016, 32/2016, 34/2016, CIVIL MISC. APPEAL NO.184/2016 IN CONST. PETITION NO.NIL/2016, CIVIL MISC. APPLICATION 7367/2016 IN CONST. PETITION NO.2/2017, 30/2017, 41/2018, CIVIL MISC. APPEAL NO.202/2016 IN CONST. PETITION NO.NIL/2016, CONST. PETITION NO.49/2018, 55/2018, 30/2015, 31/2015 32/2015, 36/2015, 64/2015, 6/2017 IN CIVIL MISC. APPEAL NO.31/2017, CONST. PETITION NO.61/2017 IN CIVIL MISC. APPEAL NO.243/2017, CONST. PETITION NO.18/2018 AND CIVIL MISC. APPLICATION NO.10872/2018 IN CONST. PETITION NO.16/2015 Const.P.50/2018: Civil Aviation Authority Vs. Supreme Appellate Court Gilgit Baltistan etc. Const.P.51/2018: Prince Saleem Khan Vs. Registrar Supreme Appellate Court Gilgit Baltistan etc. Const.P.63/2011: Dr. Ghulam Abbas Vs. Federation of Pakistan etc. C.M.A.4922/2011: Application for impleadment by Supreme in Const.P.63/2011 Appellate Court Bar Association Gilgit-Baltistan C.M.A.5382/2011: Application for Impleadment Dolat Jan in Const.P.63/2011 C.M.A.695/2012: Application for Impleadment by Wazir Farman Ali in Const.P.63/2011 C.M.A.724/2017: Application for Impleadment by Taqdir Ali Khan v. -

IN the SUPREME COURT of PAKISTAN (Appellate Jurisdiction)

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN (Appellate Jurisdiction) PRESENT: MR. JUSTICE MIAN SAQIB NISAR, HCJ MR. JUSTICE UMAR ATA BANDIAL MR. JUSTICE IJAZ UL AHSAN CONSTITUTION PETITION NO.134 OF 2012 AND CIVIL MISC. APPLICATION NO.1864 OF 2010 IN CONSTITUTION PETITION NO.9 OF 2005 AND CIVIL MISC. APPLICATIONS NO.1939 OF 2014, 5959 OF 2016, 4095, 1793, 2876, 2996, 3014 AND 6672 OF 2018 IN CONSTITUTION PETITION NO.134 OF 2012 AND CIVIL MISC. APPLICATIONS NO.3034, 3048, 3051 AND 6247 OF 2018 IN CIVIL MISC. APPLICATION NO.1864 OF 2010 Const.P.134/2012: Pakistan Bar Council through its Chairman v. Federal Government through Establishment Division and others C.M.A.1864/2010: Article by Aredshir Cowasjee in Daily Dawn dated 27.06.2010 titled “Looking the Future” regarding standards of professional ethics in the legal profession. C.M.A.1939/2014: Application by Pakistan Bar Council for Impleading Universities as respondents. C.M.A.5959/2016: Application in Respect of Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto University of Law (SZABUL) through its Registrar v. Federal Government through Establishment Division and others C.M.A.1793/2018: Impleadment application by Muhammad Amin Sandhila C.M.A.2876/2018: Concise Statement by KPK Law Colleges in reply to show cause notices issued vide order dated 6.3.2018. C.M.A.2996/2018: Impleadment application by Pakistan Bar Council through Chairman Legal Education Committee v. The Federal Government thr. Secretary Establishment and others C.M.A.3014/2018: Impleadment application by Islamabad Bar Council C.M.A.3034/2018: Concise Statement on behalf of respondent No.2 College of Legal & Ethical Studies (Coles), Abbottabad.