The Pakistani Lawyers' Movement and the Popular

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pakistan” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 124, folder “Pakistan” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 124 of The Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library MEMORANDUM THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON January 10, 1975 MEMORANDUM FOR: RON NESSEN FROM: LESJANKA SUBJECT: Morning Press Items IT EMS TO BE ANNOUNCED OR VOLUNTEERED: 1. Announcement of Bhutto Visit: 11The President has invited the Prime Minister of Pakistan Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Begum Nusrat Bhutto to Washington for an Official Visit February 4-7. The Prime Minister will meet with President Ford on February 5 and with other high level officials during his visit. The President and Mrs. Ford will host a dinner at the White House in honor of the Prime Minister and Begum Nusrat Bhutto on the evening of February 5. Secretary Kissinger conveyed this invitation to Prime Minister Bhutto during his visit to Pakistan October 31 - November 1, 1974. -

Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan

Politics of Exclusion: Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan by Sadia Saeed A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor George P. Steinmetz, Chair Professor Howard A. Kimeldorf Associate Professor Fatma Muge Gocek Associate Professor Genevieve Zubrzycki Professor Mamadou Diouf, Columbia University © Sadia Saeed 2010 2 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my parents with my deepest love, respect and gratitude for the innumerable ways they have supported my work and choices. ii Acknowledgements I would like to begin by acknowledging the immense support my parents have given me every step of the way during my (near) decade in graduate school. I have dedicated this dissertation to them. My ammi and baba have always believed in my capabilities to accomplish not only this dissertation but much more in life and their words of love and encouragement have continuously given me the strength and the will to give my research my very best. My father‘s great enthusiasm for this project, his intellectual input and his practical help and advice during the fieldwork of this project have been formative to this project. I would like to thank my dissertation advisor George Steinmetz for the many engaged conversations about theory and methods, for always pushing me to take my work to the next level and above all for teaching me to recognize and avoid sloppiness, caricatures and short-cuts. It is to him that I owe my greatest intellectual debt. -

Announcement the International Historical, Educational, Charitable and Human Rights Society Memorial, Based in Moscow, Asks

Network of Concerned Historians NCH Campaigns Year Year Circular Country Name original follow- up 2017 88 Russia Yuri Dmitriev 2020 Announcement The international historical, educational, charitable and human rights society Memorial, based in Moscow, asks you to sign a petition in support of imprisoned historian and Gulag researcher Yuri Dmitriev in Karelia. The petition calls for Yuri Dmitriev to be placed under house arrest for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic or until his court case is over. The petition can be signed in Russian, English, French, Italian, German, Hebrew, Polish, Czech, and Finnish. It can be found here and here. This is the second petition for Yuri Dmitriev. The first, from 2017, can be found here. Please find below: (1) a NCH case summary (2) the petition text in English. P.S. Another historian, Sergei Koltyrin – who had defended Yuri Dmitriev and was subsequently imprisoned under charges similar to his – died in a prison hospital in Medvezhegorsk, Karelia, on 2 April 2020. Please sign the petition immediately. ========== NCH CASE SUMMARY On 13 December 2016, the Federal Security Service (FSB) arrested Karelian historian Yuri Dmitriev (1956–) and held him in remand prison on charges of “preparing and circulating child pornography” and “depravity involving a minor [his foster child, eleven or twelve years old in 2017].” The arrest came after an anonymous tip: the individual and his motives, as well as how he got the private information, remain unknown. Dmitriev said the “pornographic” photos of his foster child were taken because medical workers had asked him to monitor the health and development of the girl, who was malnourished and unhealthy when he and his wife took her in at age three with the intention of adopting her. -

Pakistan: Arrival and Departure

01-2180-2 CH 01:0545-1 10/13/11 10:47 AM Page 1 stephen p. cohen 1 Pakistan: Arrival and Departure How did Pakistan arrive at its present juncture? Pakistan was originally intended by its great leader, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, to transform the lives of British Indian Muslims by providing them a homeland sheltered from Hindu oppression. It did so for some, although they amounted to less than half of the Indian subcontinent’s total number of Muslims. The north Indian Muslim middle class that spearheaded the Pakistan movement found itself united with many Muslims who had been less than enthusiastic about forming Pak- istan, and some were hostile to the idea of an explicitly Islamic state. Pakistan was created on August 14, 1947, but in a decade self-styled field marshal Ayub Khan had replaced its shaky democratic political order with military-guided democracy, a market-oriented economy, and little effective investment in welfare or education. The Ayub experiment faltered, in part because of an unsuccessful war with India in 1965, and Ayub was replaced by another general, Yahya Khan, who could not manage the growing chaos. East Pakistan went into revolt, and with India’s assistance, the old Pakistan was bro- ken up with the creation of Bangladesh in 1971. The second attempt to transform Pakistan was short-lived. It was led by the charismatic Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who simultaneously tried to gain control over the military, diversify Pakistan’s foreign and security policy, build a nuclear weapon, and introduce an economic order based on both Islam and socialism. -

The Suppression of Communism Act

The Suppression of Communism Act http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuun1972_07 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org The Suppression of Communism Act Alternative title Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against ApartheidNo. 7/72 Author/Creator United Nations Centre against Apartheid; Yengwa, Massabalala B. Publisher Department of Political and Security Council Affairs Date 1972-03-00 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1972 Source Northwestern University Libraries Description INTRODUCTION. Criticism of Bill in Parliament and by the Bar. The real purpose of the Act. -

Mr.Justice Salahuddin Mirza ACADEMIC QUALIFICATION

Mr.Justice Salahuddin Mirza 08.01.2007 to 07.01.2010 ACADEMIC QUALIFICATION • Matriculation in 1950 from Sindh University (B.V.S. Parsi High School, Karachi). • Intermediate and B.A. from Sindh Muslim College Karachi in 1954. • L.L.B from Sindh Muslim Law College in 1958. • Appeared in the P.C.S. (Judicial Branch) examination of the West Pakistan Public Service Commission in 1959 and qualified the same, standing first in English language. EXPERIENCE • On appointment, his services were placed at the disposal of Lahore Bench of West Pakistan High Court. • First posting at Multan in 1960. Further postings in Lahore, Pakpattan and again in Lahore and Dera Ghazi Khan. • On the break-up of one Unit in 1970, the all West Pakistan Services were bifurcated on the basis of domicile and, since his domicile was of Karachi. • He was repatriated to Sindh and posted in Thatta as Civil Judge and FCM. • Promoted as Additional District & Sessions Judge and posted in Karachi from 1972 to 1974 and at Larkana from 1975 to 1976. • Served as Judge of the Labour Court Sukkur (1977-79) and Judge of Labour Court at Karachi (1979 to 1981). • Promoted as District and Sessions Judge in 1980. • Served in the Law Division, Ministry of Justice and Parliamentary Affairs, Islamabad, as Deputy Solicitor/Joint Secretary from February 1981 to March, 1985. • On completion of deputation in the Law Division was posted at Karachi as Chairman Appellate Tribunal (Local Councils) where he served from April, 1985, to April,1988. • Served as the Registrar of the Sindh High Court from April 1988 to September, 1988, when elevated to the High Court. -

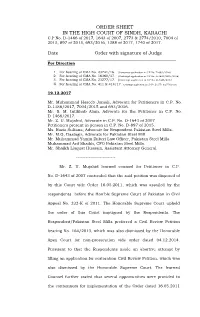

ORDER SHEET in the HIGH COURT of SINDH, KARACHI C.P No

ORDER SHEET IN THE HIGH COURT OF SINDH, KARACHI C.P No. D-1466 of 2017, 1643 of 2007, 2773 & 2774/2010, 7004 of 2015, 897 of 2015, 693/2016, 1388 of 2017, 1740 of 2017. _________________________________________________________ Date Order with signature of Judge ________________________________________________________ For Direction 1. For hearing of CMA No. 23741/16. (Contempt application in C.P No. D-693/2016) 2. For hearing of CMA No. 16360/17. (Contempt application in C.P No. D-1643/2007/2016) 3. For hearing of CMA No. 23277/17. (Contempt application in C.P No. D-1466/2017) 4. For hearing of CMA No. 411 & 414/17. (Contempt application in C.P No. D-2773 & 2774/2010) 19.12.2017 Mr. Muhammad Haseeb Jamali, Advocate for Petitioners in C.P. No. D-1388/2017, 7004/2015 and 693/2016. Mr. S. M. Intikhab Alam, Advocate for the Petitioner in C.P. No. D-1466/2017. Mr. Z. U. Mujahid, Advocate in C.P. No. D-1643 of 2007 Petitioners present in person in C.P. No. D-897 of 2015. Ms. Razia Sultana, Advocate for Respondent Pakistan Steel Mills. Mr. M.G, Dastagir, Advocate for Pakistan Steel Mill Mr. Muhammad Yamin Zuberi Law Officer, Pakistan Steel Mills. Muhammad Arif Shaikh, CFO Pakistan Steel Mills. Mr. Shaikh Liaquat Hussain, Assistant Attorney General. ------------------------- Mr. Z. U. Mujahid learned counsel for Petitioner in C.P. No. D-1643 of 2007 contended that the said petition was disposed of by this Court vide Order 16.05.2011, which was assailed by the respondents before the Hon’ble Supreme Court of Pakistan in Civil Appeal No. -

IN the SUPREME COURT of PAKISTAN (Appellate Jurisdiction)

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN (Appellate Jurisdiction) Present: Mr. Justice Manzoor Ahmad Malik Mr. Justice Syed Mansoor Ali Shah C.P.1290-L/2019 (Against the Order of Lahore High Court, Lahore dated 31.01.2019, passed in W.P. No. 5898/2019) D. G. Khan Cement Company Ltd. ...….Petitioner(s) Versus Government of Punjab through its Chief Secretary, Lahore, etc. …….Respondent(s) For the petitioner(s): Mr. Salman Aslam Butt, ASC. For the respondent(s): Ms. Aliya Ejaz, Asstt. A.G. Dr. Khurram Shahzad, D.G. EPA. M. Nawaz Manik, Director Law, EPA. M. Younas Zahid, Dy. Director. Fawad Ali, Dy. Director, EPA (Chakwal). Kashid Sajjan, Asstt. Legal, EPA. Rizwan Saqib Bajwa, Manager GTS. Research Assistance: Hasan Riaz, Civil Judge-cum-Research Officer at SCRC.1 Date of hearing: 11.02.2021 JUDGEMENT Syed Mansoor Ali Shah, J.- The case stems from Notification dated 08.03.2018 (“Notification”) issued by the Industries, Commerce and Investment Department, Government of the Punjab (“Government”), under sections 3 and 11 of the Punjab Industries (Control on Establishment and Enlargement) Ordinance, 1963 (“Ordinance”), introducing amendments in Notification dated 17.09.2002 to the effect that establishment of new cement plants, and enlargement and expansion of existing cement plants shall not be allowed in the “Negative Area” falling within the Districts Chakwal and Khushab. 2. The petitioner owns and runs a cement manufacturing plant in Kahoon Valley in the Salt Range at Khairpur, District Chakwal and feels wronged of the Notification for the reasons, -

Pakistan's 2008 Elections

Pakistan’s 2008 Elections: Results and Implications for U.S. Policy name redacted Specialist in South Asian Affairs April 9, 2008 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov RL34449 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Pakistan’s 2008 Elections: Results and Implications for U.S. Policy Summary A stable, democratic, prosperous Pakistan actively working to counter Islamist militancy is considered vital to U.S. interests. Pakistan is a key ally in U.S.-led counterterrorism efforts. The history of democracy in Pakistan is a troubled one marked by ongoing tripartite power struggles among presidents, prime ministers, and army chiefs. Military regimes have ruled Pakistan directly for 34 of the country’s 60 years in existence, and most observers agree that Pakistan has no sustained history of effective constitutionalism or parliamentary democracy. In 1999, the democratically elected government of then-Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif was ousted in a bloodless coup led by then-Army Chief Gen. Pervez Musharraf, who later assumed the title of president. In 2002, Supreme Court-ordered parliamentary elections—identified as flawed by opposition parties and international observers—seated a new civilian government, but it remained weak, and Musharraf retained the position as army chief until his November 2007 retirement. In October 2007, Pakistan’s Electoral College reelected Musharraf to a new five-year term in a controversial vote that many called unconstitutional. The Bush Administration urged restoration of full civilian rule in Islamabad and called for the February 2008 national polls to be free, fair, and transparent. U.S. criticism sharpened after President Musharraf’s November 2007 suspension of the Constitution and imposition of emergency rule (nominally lifted six weeks later), and the December 2007 assassination of former Prime Minister and leading opposition figure Benazir Bhutto. -

Comparative Constitutional Law SPRING 2012

Comparative Constitutional Law SPRING 2012 PROFESSOR STEPHEN J. SCHNABLY Office: G472 http://osaka.law.miami.edu/~schnably/courses.html Tel.: 305-284-4817 E-mail: [email protected] SUPPLEMENTARY READINGS: TABLE OF CONTENTS Reference re Secession of Quebec, [1998] 2 S.C.R. 217 .................................................................1 Supreme Court Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. S-26. An Act respecting the Supreme Court of Canada................................................................................................................................11 INS v. Chadha, 462 U.S. 919 (1983) .............................................................................................12 Kenya Timeline..............................................................................................................................20 Laurence Juma, Ethnic Politics and the Constitutional Review Process in Kenya, 9 Tulsa J. Comp. & Int’l L. 471 (2002) ..........................................................................................23 Mary L. Dudziak, Working Toward Democracy: Thurgood Marshall and the Constitution of Kenya, 56 Duke L.J. 721 (2006)....................................................................................26 Laurence Juma, Ethnic Politics and the Constitutional Review Process in Kenya, 9 Tulsa J. Comp. & Int’l L. 471 (2002) .......................................................................................34 Migai Akech, Abuse of Power and Corruption in Kenya: Will the New Constitution Enhance Government -

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts Shahnaz Begum Laghari PhD University of York Women’s Studies March 2016 Abstract The aim of this project is to investigate the phenomenon of honour-related violence, the most extreme form of which is honour killing. The research was conducted in Sindh (one of the four provinces of Pakistan). The main research question is, ‘Are these killings for honour?’ This study was inspired by a need to investigate whether the practice of honour killing in Sindh is still guided by the norm of honour or whether other elements have come to the fore. It is comprised of the experiences of those involved in honour killings through informal, semi- structured, open-ended, in-depth interviews, conducted under the framework of the qualitative method. The aim of my thesis is to apply a feminist perspective in interpreting the data to explore the tradition of honour killing and to let the versions of the affected people be heard. In my research, the women who are accused as karis, having very little redress, are uncertain about their lives; they speak and reveal the motives behind the allegations and killings in the name of honour. The male killers, whom I met inside and outside the jails, justify their act of killing in the name of honour, culture, tradition and religion. Drawing upon interviews with thirteen women and thirteen men, I explore and interpret the data to reveal their childhood, educational, financial and social conditions and the impacts of these on their lives, thoughts and actions. -

U.S.-Pakistan Engagement: the War on Terrorism and Beyond

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Touqir Hussain While the war on terrorism may have provided the rationale for the latest U.S. engagement with Pakistan, the present relationship between the United States and Pakistan is at the crossroads of many other issues, such as Pakistan’s own U.S.-Pakistan reform efforts, America’s evolving strategic relationship with South Asia, democracy in the Muslim world, and the dual problems of religious extremism and nuclear proliferation. As a result, Engagement the two countries have a complex relationship that presents a unique challenge to their respective policymaking communities. The War on Terrorism and Beyond This report examines the history and present state of U.S.-Pakistan relations, addresses the key challenges the two countries face, and concludes with specific policy recommendations Summary for ensuring the relationship meets the needs • The current U.S. engagement with Pakistan may be focused on the war on terrorism, of both the United States and Pakistan. It was written by Touqir Hussain, a senior fellow at the but it is not confined to it. It also addresses several other issues of concern to the United States Institute of Peace and a former United States: national and global security, terrorism, nuclear proliferation, economic senior diplomat from Pakistan, who served as and strategic opportunities in South Asia, democracy, and anti-Americanism in the ambassador to Japan, Spain, and Brazil. Muslim world. • The current U.S. engagement with Pakistan offers certain lessons for U.S.