The Regional Historian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Secondary School and Academy Admissions

Secondary School and Academy Admissions INFORMATION BOOKLET 2021/2022 For children born between 1st September 2009 and 31st August 2010 Page 1 Schools Information Admission number and previous applications This is the total number of pupils that the school can admit into Year 7. We have also included the total number of pupils in the school so you can gauge its size. You’ll see how oversubscribed a school is by how many parents had named a school as one of their five preferences on their application form and how many of these had placed it as their first preference. Catchment area Some comprehensive schools have a catchment area consisting of parishes, district or county boundaries. Some schools will give priority for admission to those children living within their catchment area. If you live in Gloucestershire and are over 3 miles from your child’s catchment school they may be entitled to school transport provided by the Local Authority. Oversubscription criteria If a school receives more preferences than places available, the admission authority will place all children in the order in which they could be considered for a place. This will strictly follow the priority order of their oversubscription criteria. Please follow the below link to find the statistics for how many pupils were allocated under the admissions criteria for each school - https://www.gloucestershire.gov.uk/education-and-learning/school-admissions-scheme-criteria- and-protocol/allocation-day-statistics-for-gloucestershire-schools/. We can’t guarantee your child will be offered one of their preferred schools, but they will have a stronger chance if they meet higher priorities in the criteria. -

Swindon and Its Environs

•/ BY THE SAME AUTHOR. ARTHUR YOUNG ANNOUNCES FOR PUBLICATION DURING 1897. THE HISTORY OF MALMESBURY ABBEY by Richard Jefferies, Edited, with Histori- cal Notes, by Grace Toplis. Illustrated by Notes on the present state of the Abbey Church, and reproductions from Original Drawings by Alfred Alex. Clarke (Author of a Monograph on Wells Cathedral). London : SiMPKiN, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., Ltd. V* THREE HUNDRED AND FIFTY COPIES OF THIS EDITION PRINTED FOR SALE r JEFFERIES' LAND A History of Swindon and its Environs pi o I—I I—I Ph < u -^ o u > =St ?^"^>^ittJ JEFFERIES' LAND A History of Swindon and its Environs BY THE LATE RICHARD JEFFERIES EDITED WITH NOTES BY GRACE TOPLIS WITH MAP AND ILLUSTRATIONS London Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co Ltd Wells, Somerset : Arthur Young MDCCCXCVI ^y^' COPYRIGHT y4// Rights Reserved CONTENTS CHAP. LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS CHAP. PAGE 1. Ivy-Church. Avebury Font , Fro7itispiece 2. Jefferies' House, Victorl^, Street, ' Swindon I. i 3. The Lawn, Swindon I. 4. Ruins of Holyrood Church 5. The Reservoir, Coate . 6. Wanborough Church , . 7. Entrance to Swindon from Coate 8. Marlborough Lane 9. Day House Farm, Coate 10. Chisledon Church 11. Jefferies' House, Coate 12. West Window, Fairford Church Note. —The illustrations are reproductions from drawings by Miss Agnes Taylor, Ilminster, mostly from photographs taken especially by Mr. Chas. Andrew, Swindon. viii INTRODUCTION T IFE teaches no harder lesson to any man I ^ than the bitter truth—as true as bitter— that ''A prophet is not without honour, save hi his own country, and in his own housed Andfo7'ei7iost among modern prophets who have had to realize its bitterness stands Richard '' Jefferies, the ''prophet'' of field and hedge- " row and all the simple daily beauty which lies " about tis on every hand. -

Issue 37 | Apr 2018 Comedy, Literature & Film in Stroud

AN INDEPENDENT, FREE MONTHLY GUIDE TO MUSIC, ART, THEATRE, ISSUE 37 | APR 2018 COMEDY, LITERATURE & FILM IN STROUD. WWW.GOODONPAPER.INFO ISSUE #37 Inside: Annual Site Festival: Record Festival Moomins & Store Day Guide The Comet 2018 + The Clay Loft | Mark Huband | Bandit | Film Posters Reinterpreted Cover image by Joe Magee Joe image by Cover #37 | Apr 2018 EDITOR Advertising/Editorial/Listings: Editor’s Note Alex Hobbis [email protected] DESIGNER Artwork and Design Welcome To The Thirty Seventh Issue Of Good On Adam Hinks [email protected] Paper – Your Free Monthly Guide To Music Concerts, Art Exhibitions, Theatre Productions, Comedy Shows, ONLINE FACEBOOK TWITTER Film Screenings And Literature Events In Stroud… goodonpaper.info /GoodOnPaperStroud @GoodOnPaper_ Well Happy Birthday to us…Good On Paper is three! And we’ve gone a bit bumper. 32 PRINTED BY: pages this month – the most pages we have ever printed in one issue. All for you. To read. Then maybe recycle. Or use as kindling (these vegetable inks burn remarkably well). Tewkesbury Printing Company With it being our anniversary issue we’ve made a few design changes – specifically to the universal font and also to the front cover. For the next year we will be inviting some of our favourite local artists to design the front cover image – simply asking them to supply a piece of new work which might relate to one of the articles featured in that particular SPONSORED BY: issue. This month we asked our friend the award winning film maker and illustrator Joe Magee... Well that’s it for now, hope you enjoy this bigger issue of Good On Paper. -

Outreach Residential Activities

Outreach Residential Activities 2017/18 2017/18 RESIDENTIAL ACTIVITY REPORT: 16 DECEMBER 2018 University of Gloucestershire Widening Participation and Outreach - Data & Evaluation Officer, Partnerships Manager 1 Residential Report Outreach and Widening Participation Team, University of Gloucestershire Each year, the Outreach team organises and delivers two separate Residential Events for Year 10 and Year 12 students with the intention of providing an intensive experience on a university campus. The residential activities aim to build higher education (HE) knowledge to enable young people to make an informed decision about their future. Students are provided with an opportunity to learn more about the subjects that are available and the processes required to apply for HE. It is hoped that students will increase their self-confidence in their ability to attend higher education and develop a sense of belonging at university, as well as reduce barriers to participate in higher education. Both residentials take place over a four day period, with the first day allowing time and space for students to settle in and socialise with each other and the summer school staff. Student Ambassadors live residentially for the duration of each summer school, supporting the running of the events and providing their own insights into university life and their routes to higher education. Students who attend the Year 10 residential take part in a wider range of academic taster sessions while Year 12 students choose a subject strand to follow. This is so that they can try a range of courses within an Academic School to provide more insight into which course they might choose to study in the future. -

5 June) (11-25 11.00-16.00 Sat: : 12.00-23.00, 12.00-23.00, : Mon-Thu 11.00-15.00 Wed-Sat: 9.00-21.00, : Mon-Thu -18.45, 9.30 : Mon-Fri

Community Swindon #SwindonArtTrail 7 Artsite 9 Swindon 11 Centre @ 13 Museum and 15 The Hop Inn 16 Swindon Central Library Christ Church Art Gallery Marriott Hotel www.artsite.ltd.uk www.swindon.gov.uk/libraries www.book-online.co.uk/cccc www.swindonmuseumandartgallery.org.uk www.hopinnswindon.co.uk www.swindonmarriott.co.uk 5 June - 3 July 2016 July 3 - June 5 Number Nine Gallery, 01793 463238 01793 617237 01793 466556 01793 976833 01793 512121 Theatre Square Regent Circus Cricklade Street Bath Road 7 Devizes Road Pipers Way SN1 1QN SN1 1QG SN1 3HB SN1 4BA SN1 4BJ SN3 1SH Sat: 11.00-16.00 (11-25 June) Mon-Fri: 9.30 -18.45, Mon-Thu: 9.00-21.00, Wed-Sat: 11.00-15.00 Mon-Thu: 12.00-23.00, Sat: 9.30-15.45, Fri: 9.00-17.00, Fri-Sat: 12.00-00.00, Sun: 11.00-14.45 Sat: 9.00-12.00, Sun: 12.00-22.30 Sun: 9.00-12.30 4 Darkroom 14 The Core Espresso Swindon www.darkroomespresso.com www.thecoreswindon.com 11 Faringdon Road, SN1 5AR 01793 610300 4 Devizes Road Mon-Fri: 8.00-17.30, SN1 4BJ Sat: 9.00-17.30, Sun: 10.00-16.00 Mon-Fri: 8.00-15.00, Sat: 8.00-16.00 Map © Mark Worrall & Dona Bradley Venue illustrations © Dona Bradley Cover images © David Robinson The 3 The Glue Pot 12 Midcounties Co-operative www.hopback.co.uk/ www.midcounties.coop our-pubs/the-gluepot.html 01793 693114 01793 497420 High Street 5 Emlyn Square, SN1 5BP SN1 3EG Mon: 16.30-23.00, Mon-Sat: 7.00-22.00 Tue-Thu: 12.00-23.00, Sun: 10.00-16.00 Fri-Sat: 11.30-23.00, Sun: 12.00-22.30 STEAM 2 Museum of the Great 1 St Augustine’s 5 Cambria Bridge 6 Swindon 8 Swindon 10 The Beehive Western -

Cheltenham Borough Council and Tewkesbury Borough Council Final Assessment Report November 2016

CHELTENHAM BOROUGH COUNCIL AND TEWKESBURY BOROUGH COUNCIL FINAL ASSESSMENT REPORT NOVEMBER 2016 QUALITY, INTEGRITY, PROFESSIONALISM Knight, Kavanagh & Page Ltd Company No: 9145032 (England) MANAGEMENT CONSULTANTS Registered Office: 1 -2 Frecheville Court, off Knowsley Street, Bury BL9 0UF T: 0161 764 7040 E: [email protected] www.kkp.co.uk CHELTENHAM AND TEWKESBURY COUNCILS BUILT LEISURE AND SPORTS ASSESSMENT REPORT CONTENTS SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 1 SECTION 2: BACKGROUND ........................................................................................... 4 SECTION 3: INDOOR SPORTS FACILITIES ASSESSMENT APPROACH ................... 16 SECTION 4: SPORTS HALLS ........................................................................................ 18 SECTION 5: SWIMMING POOLS ................................................................................... 38 SECTION 6: HEALTH AND FITNESS SUITES ............................................................... 53 SECTION 7: SQUASH COURTS .................................................................................... 62 SECTION 8: INDOOR BOWLS ....................................................................................... 68 SECTION 9: INDOOR TENNIS COURTS ....................................................................... 72 SECTION 10: ATHLETICS ............................................................................................. 75 SECTION 11: COMMUNITY FACILITIES ...................................................................... -

Walks in Jefferies-Land 1912

Walks in Jefferies-Land 1912 Kate Tryon The RICHARD JEFFERIES SOCIETY (Registered Charity No. 1042838) was founded in 1950 to promote appreciation and study of the writings of Richard Jefferies (1848-1887). Website http://richardjefferiessociety.co.uk email [email protected] 01793 783040 The Kate Tryon manuscript In 2010, the Richard Jefferies Society published Kate Tryon’s memoir of her first visit to Jefferies’ Land in 1910. [Adventures in the Vale of the White Horse: Jefferies Land, Petton Books.] It was discovered that the author and artist had started work on another manuscript in 1912 entitled “Walks in Jefferies-Land”. However, this type-script was incomplete and designed to illustrate the places that Mrs Tryon had visited and portrayed in her oil-paintings using Jefferies’ own words. There are many pencilled-in additions to this type-script in Kate Tryon’s own hand- writing and selected words are underlined in red crayon. Page 13 is left blank, albeit that the writer does not come across as a superstitious person. The Jefferies’ quotes used are not word-perfect; neither is her spelling nor are her facts always correct. There is a handwritten note on the last page that reads: “This is supposed to be about half the book. – K.T.” The Richard Jefferies Society has edited the “Walks”, correcting obvious errors but not the use of American spelling in the main text. References for quotes have been added along with appropriate foot-notes. The Richard Jefferies Society is grateful to Kate Schneider (Kate Tryon’s grand- daughter) for allowing the manuscripts to be published and thanks Stan Hickerton and Jean Saunders for editing the booklet. -

Travel Trade Guide 2021

It’s time for WILTSHIRE Travel Trade Guide visitwiltshire.co.uk VISITWILTSHIRE Discover TIMELESS WILTSHIRE Ready to start same sense of wonder for yourself Travel trade visitors can expect a by following the Great West Way®. particularly warm reception from planning your Around a quarter of this touring accommodation providers across next group visit? route between London and Bristol Wiltshire. Indeed, Salisbury has runs through the breathtaking been welcoming visitors since There’s so much space to enjoy. landscape of Wiltshire. Along 1227. As you discover attractions After an unprecedented year of ancient paths once used by druids, such as Salisbury Cathedral and lockdown, social distancing and new pilgrims and drovers. Through lush Magna Carta and Old Sarum you’ll rules to get our heads around, we river valleys. Over rolling chalk uncover layer upon layer of history. are all searching for space to relax hills. Amid ancient woodland. Past Take time, too, to explore charming and are probably keen to avoid the picturesque towns and villages. market towns such as Bradford crowds. In Wiltshire, you’ll find rolling on Avon and Corsham. Stroll Things will look a little different open countryside and expansive through the picturesque villages to normal when businesses open views. With over 8,000 footpaths again after the 2021 lockdown. around the county there’s always “We’re Good To Go” is the official somewhere to stretch your legs off UK mark to signal that a business the beaten track! Get the most out has implemented Government of our spacious landscapes by going and industry COVID-19 guidelines for a walk, exploring by bike or trying and has a process in place to out horse riding. -

WRF NL192 July 2018

WELLS RAILWAY FRATERNITY Newsletter No.192 - July 2018 th <<< 50 ANNIVERSARY YEAR >>> www.railwells.com Thank you to those who have contributed to this newsletter. Your contributions for future editions are welcome; please contact the editor, Steve Page Tel: 01761 433418, or email [email protected] < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > Visit to STEAM Museum at Swindon on 12 June. Photo by Andrew Tucker. MODERNISATION TO PRIVATISATION, 1968 - 1997 by John Chalcraft – 8 May On the 8th May we once more welcomed John Chalcraft as our speaker. John has for many years published railway photographs and is well known for his knowledge on topics relating to our hobby. He began by informing us that there were now some 26,000 photographs on his website! From these, he had compiled a presentation entitled 'From Modernisation to Privatisation', covering a 30-year period from 1968 (the year of the Fraternity's founding) until 1997. His talk was accompanied by a couple of hundred illustrations, all of very high quality, which formed a most comprehensive review of the railway scene during a period when the railways of this country were subjected to great changes. We started with a few photos of the last steam locomotives at work on BR and then were treated to a review of the new motive power that appeared in the 20 years or so from the Modernisation Plan of 1955. John managed to illustrate nearly every class of diesel and electric locomotive that saw service in this period, from the diminutive '03' shunter up to the Class '56' 3,250 hp heavy freight locomotive - a total of over 50 types. -

Design & Access Statement Incorporating a Supporting Planning Statement

Design & Access Statement incorporating a supporting Planning Statement Signal Point, Station Road, Swindon On behalf of Narbeth Management Ltd D August 2018 C8643, Signal Point, Swindon Signal Point Narbeth Management Ltd Author: ER Checked by: MMD Approved by: LMD Position: Director Date: 13.08.2018 Project Code: C8643 DPDS Consulting Group Old Bank House 5 Devizes Road Old Town Swindon SN1 4BJ Copyright The contents of this document must not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written consent of © DPDS Consulting Group Mapping reproduced from Ordnance Survey mapping with the sanction of the Controller of H. M. Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright Reserved. DPDS Consulting Group. Licence No AL100018937 Signal Point, Swindon August 2018 Planning/Design and Access Statement © DPDS Group Ltd, Layout by DPDS Graphics iii Signal Point, Swindon DPDS Consulting Group Old Bank House 5 Devizes Road Old Town Swindon SN1 4BJ August 2018 Signal Point, Swindon iv © DPDS Group Ltd, Layout by DPDS Graphics Planning/Design and Access Statement 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Site context and analysis 3.0 Relevant Planning History 4.0 Planning Policy context 5.0 Development Proposals 6.0 Design Rationale 7.0 Conclusions Signal Point, Swindon August 2018 Planning/Design and Access Statement © DPDS Group Ltd, Layout by DPDS Graphics v 1.0 Introduction 1.0 Introduction August 2018 Signal Point, Swindon 6 © DPDS Group Ltd, Layout by DPDS Graphics Planning/Design and Access Statement 1.0 Introduction 1.1 This Design and Access Statement incorporating a 1.7 The Vision underpinning the Signal Point proposals is to supporting Planning Statement has been prepared by regenerate a tired and dated building into an attractive, DPDS Consulting Group and is submitted in support well designed building that will encourage investment of the full planning application for external façade and re-use. -

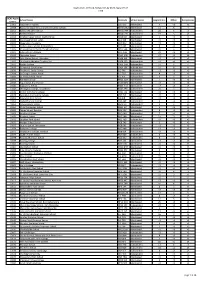

Secondaryschoolspendinganaly

www.tutor2u.net Analysis of Resources Spend by School Total Spending Per Pupil Learning Learning ICT Learning Resources (not ICT Learning Resources (not School Resources ICT) Total Resources ICT) Total Pupils (FTE) £000 £000 £000 £/pupil £/pupil £/pupil 000 Swanlea School 651 482 1,133 £599.2 £443.9 £1,043.1 1,086 Staunton Community Sports College 234 192 426 £478.3 £393.6 £871.9 489 The Skinners' Company's School for Girls 143 324 468 £465.0 £1,053.5 £1,518.6 308 The Charter School 482 462 944 £444.6 £425.6 £870.2 1,085 PEMBEC High School 135 341 476 £441.8 £1,117.6 £1,559.4 305 Cumberland School 578 611 1,189 £430.9 £455.1 £885.9 1,342 St John Bosco Arts College 434 230 664 £420.0 £222.2 £642.2 1,034 Deansfield Community School, Specialists In Media Arts 258 430 688 £395.9 £660.4 £1,056.4 651 South Shields Community School 285 253 538 £361.9 £321.7 £683.6 787 Babington Community Technology College 268 290 558 £350.2 £378.9 £729.1 765 Queensbridge School 225 225 450 £344.3 £343.9 £688.2 654 Pent Valley Technology College 452 285 737 £339.2 £214.1 £553.3 1,332 Kemnal Technology College 366 110 477 £330.4 £99.6 £430.0 1,109 The Maplesden Noakes School 337 173 510 £326.5 £167.8 £494.3 1,032 The Folkestone School for Girls 325 309 635 £310.9 £295.4 £606.3 1,047 Abbot Beyne School 260 134 394 £305.9 £157.6 £463.6 851 South Bromsgrove Community High School 403 245 649 £303.8 £184.9 £488.8 1,327 George Green's School 338 757 1,096 £299.7 £670.7 £970.4 1,129 King Edward VI Camp Hill School for Boys 211 309 520 £297.0 £435.7 £732.7 709 Joseph -

2014 Admissions Cycle

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2014 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 4 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 11 5 4 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 20 5 3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 19 3 <3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 3 <3 <3 10020 Manshead School, Luton LU1 4BB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 4 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 20 6 5 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 21 <3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 27 13 13 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 10 4 4 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 14 8 8 10036 The Marist Senior School SL5 7PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent 4 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 6 3 3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 7 <3 <3 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 20 6 6 10046 Didcot Sixth Form College OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained