Walks in Jefferies-Land 1912

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swindon and Its Environs

•/ BY THE SAME AUTHOR. ARTHUR YOUNG ANNOUNCES FOR PUBLICATION DURING 1897. THE HISTORY OF MALMESBURY ABBEY by Richard Jefferies, Edited, with Histori- cal Notes, by Grace Toplis. Illustrated by Notes on the present state of the Abbey Church, and reproductions from Original Drawings by Alfred Alex. Clarke (Author of a Monograph on Wells Cathedral). London : SiMPKiN, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., Ltd. V* THREE HUNDRED AND FIFTY COPIES OF THIS EDITION PRINTED FOR SALE r JEFFERIES' LAND A History of Swindon and its Environs pi o I—I I—I Ph < u -^ o u > =St ?^"^>^ittJ JEFFERIES' LAND A History of Swindon and its Environs BY THE LATE RICHARD JEFFERIES EDITED WITH NOTES BY GRACE TOPLIS WITH MAP AND ILLUSTRATIONS London Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co Ltd Wells, Somerset : Arthur Young MDCCCXCVI ^y^' COPYRIGHT y4// Rights Reserved CONTENTS CHAP. LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS CHAP. PAGE 1. Ivy-Church. Avebury Font , Fro7itispiece 2. Jefferies' House, Victorl^, Street, ' Swindon I. i 3. The Lawn, Swindon I. 4. Ruins of Holyrood Church 5. The Reservoir, Coate . 6. Wanborough Church , . 7. Entrance to Swindon from Coate 8. Marlborough Lane 9. Day House Farm, Coate 10. Chisledon Church 11. Jefferies' House, Coate 12. West Window, Fairford Church Note. —The illustrations are reproductions from drawings by Miss Agnes Taylor, Ilminster, mostly from photographs taken especially by Mr. Chas. Andrew, Swindon. viii INTRODUCTION T IFE teaches no harder lesson to any man I ^ than the bitter truth—as true as bitter— that ''A prophet is not without honour, save hi his own country, and in his own housed Andfo7'ei7iost among modern prophets who have had to realize its bitterness stands Richard '' Jefferies, the ''prophet'' of field and hedge- " row and all the simple daily beauty which lies " about tis on every hand. -

5 June) (11-25 11.00-16.00 Sat: : 12.00-23.00, 12.00-23.00, : Mon-Thu 11.00-15.00 Wed-Sat: 9.00-21.00, : Mon-Thu -18.45, 9.30 : Mon-Fri

Community Swindon #SwindonArtTrail 7 Artsite 9 Swindon 11 Centre @ 13 Museum and 15 The Hop Inn 16 Swindon Central Library Christ Church Art Gallery Marriott Hotel www.artsite.ltd.uk www.swindon.gov.uk/libraries www.book-online.co.uk/cccc www.swindonmuseumandartgallery.org.uk www.hopinnswindon.co.uk www.swindonmarriott.co.uk 5 June - 3 July 2016 July 3 - June 5 Number Nine Gallery, 01793 463238 01793 617237 01793 466556 01793 976833 01793 512121 Theatre Square Regent Circus Cricklade Street Bath Road 7 Devizes Road Pipers Way SN1 1QN SN1 1QG SN1 3HB SN1 4BA SN1 4BJ SN3 1SH Sat: 11.00-16.00 (11-25 June) Mon-Fri: 9.30 -18.45, Mon-Thu: 9.00-21.00, Wed-Sat: 11.00-15.00 Mon-Thu: 12.00-23.00, Sat: 9.30-15.45, Fri: 9.00-17.00, Fri-Sat: 12.00-00.00, Sun: 11.00-14.45 Sat: 9.00-12.00, Sun: 12.00-22.30 Sun: 9.00-12.30 4 Darkroom 14 The Core Espresso Swindon www.darkroomespresso.com www.thecoreswindon.com 11 Faringdon Road, SN1 5AR 01793 610300 4 Devizes Road Mon-Fri: 8.00-17.30, SN1 4BJ Sat: 9.00-17.30, Sun: 10.00-16.00 Mon-Fri: 8.00-15.00, Sat: 8.00-16.00 Map © Mark Worrall & Dona Bradley Venue illustrations © Dona Bradley Cover images © David Robinson The 3 The Glue Pot 12 Midcounties Co-operative www.hopback.co.uk/ www.midcounties.coop our-pubs/the-gluepot.html 01793 693114 01793 497420 High Street 5 Emlyn Square, SN1 5BP SN1 3EG Mon: 16.30-23.00, Mon-Sat: 7.00-22.00 Tue-Thu: 12.00-23.00, Sun: 10.00-16.00 Fri-Sat: 11.30-23.00, Sun: 12.00-22.30 STEAM 2 Museum of the Great 1 St Augustine’s 5 Cambria Bridge 6 Swindon 8 Swindon 10 The Beehive Western -

Travel Trade Guide 2021

It’s time for WILTSHIRE Travel Trade Guide visitwiltshire.co.uk VISITWILTSHIRE Discover TIMELESS WILTSHIRE Ready to start same sense of wonder for yourself Travel trade visitors can expect a by following the Great West Way®. particularly warm reception from planning your Around a quarter of this touring accommodation providers across next group visit? route between London and Bristol Wiltshire. Indeed, Salisbury has runs through the breathtaking been welcoming visitors since There’s so much space to enjoy. landscape of Wiltshire. Along 1227. As you discover attractions After an unprecedented year of ancient paths once used by druids, such as Salisbury Cathedral and lockdown, social distancing and new pilgrims and drovers. Through lush Magna Carta and Old Sarum you’ll rules to get our heads around, we river valleys. Over rolling chalk uncover layer upon layer of history. are all searching for space to relax hills. Amid ancient woodland. Past Take time, too, to explore charming and are probably keen to avoid the picturesque towns and villages. market towns such as Bradford crowds. In Wiltshire, you’ll find rolling on Avon and Corsham. Stroll Things will look a little different open countryside and expansive through the picturesque villages to normal when businesses open views. With over 8,000 footpaths again after the 2021 lockdown. around the county there’s always “We’re Good To Go” is the official somewhere to stretch your legs off UK mark to signal that a business the beaten track! Get the most out has implemented Government of our spacious landscapes by going and industry COVID-19 guidelines for a walk, exploring by bike or trying and has a process in place to out horse riding. -

WRF NL192 July 2018

WELLS RAILWAY FRATERNITY Newsletter No.192 - July 2018 th <<< 50 ANNIVERSARY YEAR >>> www.railwells.com Thank you to those who have contributed to this newsletter. Your contributions for future editions are welcome; please contact the editor, Steve Page Tel: 01761 433418, or email [email protected] < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > < > Visit to STEAM Museum at Swindon on 12 June. Photo by Andrew Tucker. MODERNISATION TO PRIVATISATION, 1968 - 1997 by John Chalcraft – 8 May On the 8th May we once more welcomed John Chalcraft as our speaker. John has for many years published railway photographs and is well known for his knowledge on topics relating to our hobby. He began by informing us that there were now some 26,000 photographs on his website! From these, he had compiled a presentation entitled 'From Modernisation to Privatisation', covering a 30-year period from 1968 (the year of the Fraternity's founding) until 1997. His talk was accompanied by a couple of hundred illustrations, all of very high quality, which formed a most comprehensive review of the railway scene during a period when the railways of this country were subjected to great changes. We started with a few photos of the last steam locomotives at work on BR and then were treated to a review of the new motive power that appeared in the 20 years or so from the Modernisation Plan of 1955. John managed to illustrate nearly every class of diesel and electric locomotive that saw service in this period, from the diminutive '03' shunter up to the Class '56' 3,250 hp heavy freight locomotive - a total of over 50 types. -

Design & Access Statement Incorporating a Supporting Planning Statement

Design & Access Statement incorporating a supporting Planning Statement Signal Point, Station Road, Swindon On behalf of Narbeth Management Ltd D August 2018 C8643, Signal Point, Swindon Signal Point Narbeth Management Ltd Author: ER Checked by: MMD Approved by: LMD Position: Director Date: 13.08.2018 Project Code: C8643 DPDS Consulting Group Old Bank House 5 Devizes Road Old Town Swindon SN1 4BJ Copyright The contents of this document must not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written consent of © DPDS Consulting Group Mapping reproduced from Ordnance Survey mapping with the sanction of the Controller of H. M. Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright Reserved. DPDS Consulting Group. Licence No AL100018937 Signal Point, Swindon August 2018 Planning/Design and Access Statement © DPDS Group Ltd, Layout by DPDS Graphics iii Signal Point, Swindon DPDS Consulting Group Old Bank House 5 Devizes Road Old Town Swindon SN1 4BJ August 2018 Signal Point, Swindon iv © DPDS Group Ltd, Layout by DPDS Graphics Planning/Design and Access Statement 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Site context and analysis 3.0 Relevant Planning History 4.0 Planning Policy context 5.0 Development Proposals 6.0 Design Rationale 7.0 Conclusions Signal Point, Swindon August 2018 Planning/Design and Access Statement © DPDS Group Ltd, Layout by DPDS Graphics v 1.0 Introduction 1.0 Introduction August 2018 Signal Point, Swindon 6 © DPDS Group Ltd, Layout by DPDS Graphics Planning/Design and Access Statement 1.0 Introduction 1.1 This Design and Access Statement incorporating a 1.7 The Vision underpinning the Signal Point proposals is to supporting Planning Statement has been prepared by regenerate a tired and dated building into an attractive, DPDS Consulting Group and is submitted in support well designed building that will encourage investment of the full planning application for external façade and re-use. -

Swindon Heritage Strategy Foreword 1

SWINDON HERITAGE STRATEGY FOREWORD 1 Our heritage defines who we are, where we have come from, A clearer focus on our heritage will undoubtedly have a big impact and shapes our view of our future. Swindon has a rich and diverse on our regeneration plans; it will provide the backbone of our heritage, much of which is unknown and hidden from view. Whilst identity and can help us feel pride in our towns and villages. I believe our rich railway heritage is well publicised and known about, it is vital that we find new and exciting ways to fund and engage few people realise that the history of human settlement in the with our heritage in all its different forms, from visiting museums, to borough can be traced back to prehistoric times and there has enjoying our historic parks, protecting our special been human settlement here ever since. buildings and places and educating our young I am delighted that this strategy has been developed to raise the people about the history of their town. profile of heritage across the town and with our communities. Councillor David Renard Below: Medical Fund Hospital Leader, Swindon Borough Council and Chair, One Swindon Board CONTENTS 2 Page 1 - FOREWORD Pages 8/11 - THE HERITAGE OF SWINDON Leader of Swindon Borough Council, Councillor “Everything of value that has been inherited David Renard, presents the strategy document. from previous generations.” Page 2 - CONTENTS Page 12 - ONE SWINDON PRIORITIES This page. The priorities of One Swindon: the primary framework which guides this Strategy. Pages 3/4 - INTRODUCTION Page13 - ONE SWINDON PRINCIPLES A brief introduction to Swindon and the overarching Outline of the principles of One Swindon which nature of the borough’s industrial heritage. -

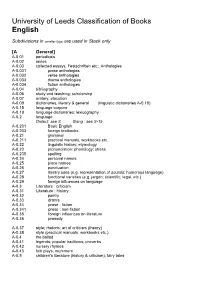

University of Leeds Classification of Books English

University of Leeds Classification of Books English Subdivisions in smaller type are used in Stack only [A General] A-0.01 periodicals A-0.02 series A-0.03 collected essays, Festschriften etc.; Anthologies A-0.031 prose anthologies A-0.032 verse anthologies A-0.033 drama anthologies A-0.034 fiction anthologies A-0.04 bibliography A-0.06 study and teaching; scholarship A-0.07 oratory; elocution A-0.09 dictionaries, literary & general (linguistic dictionaries A-0.19) A-0.15 language corpora A-0.19 language dictionaries; lexicography A-0.2 language Dialect: see S Slang : see S-15 A-0.201 Basic English A-0.203 foreign textbooks A-0.21 grammar A-0.211 practical manuals, workbooks etc. A-0.22 linguistic history; etymology A-0.23 pronunciation; phonology; stress A-0.235 spelling A-0.24 personal names A-0.25 place names A-0.26 punctuation A-0.27 literary uses (e.g. representation of sounds; humorous language) A-0.28 functional varieties (e.g. jargon; scientific, legal, etc.) A-0.29 foreign influences on language A-0.3 Literature : criticism A-0.31 Literature : history A-0.32 poetry A-0.33 drama A-0.34 prose : fiction A-0.341 prose : non-fiction A-0.35 foreign influences on literature A-0.36 prosody A-0.37 style; rhetoric; art of criticism (theory) A-0.38 style (practical manuals, workbooks etc.) A-0.4 the ballad A-0.41 legends; popular traditions; proverbs A-0.42 nursery rhymes A-0.43 folk plays; mummers A-0.5 children’s literature (history & criticism); fairy tales [B Old English] B-0.02 series B-0.03 anthologies of prose and verse Prose anthologies -

'Swindon and Its Railway Connections' by Reg Palk

IMechE Dorchester Area Lecture Review ‘Swindon and its Railway Connections’ by Reg Palk 18th June 2009, Weymouth College ‘Swindon and its Railway Connections’ presented by Reg Palk, a Swindon railway museum volunteer, held at Weymouth College on the 18th June 2009 was an informative and light hearted lecture for all those interested in Swindon and its railway heritage. The lecture commenced at 7pm and was well attended by an audience of approximate 30. With the aid of slides, Reg described the history of Swindon Railway Works which opened in January 1843 as a repair and maintenance facility for the new Great Western Railway (GWR). By 1900 the works had expanded dramatically and employed over 12,000 people and at its peak in the 1930s, the works covered over 300 acres and capable of producing three locomotives a week. The ‘STEAM - Museum of the Great Western Railway’, tells the story of the men and women who built, operated and travelled on the GWR, a network that through the pioneering vision of Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859) and others such as Sir Daniel Gooch (1816-1889) was regarded as the most advanced in the world. In 1840, Daniel Gooch, locomotive superintendent of the GWR, wrote to Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the railway's chief engineer. The letter he wrote proved decisive in Swindon's history changing it from the small market town of ‘Swindon on the hill’ with its associated canal junction into a town at the heart of the Industrial Revolution. The letter from Gooch put forward his proposal for the building of the Great Western's much-needed engine works at Swindon. -

This Is Our Heritage

THIS IS OUR HERITAGE An account of the central role played by the NEW SWINDON MECHANICS' INSTITUTION in the Cultural, Educational and Social Life of the town and district for over One Hundred Years THE UNABRIDGED TEXT OF AN ADDRESS On the illustrious History of The Mechanics' Institution at Swindon, 1843-1960 GIVEN TO A MEETING OF MEMBERS AND SUPPORTERS OF THE NEW MECHANICS' INSTITUTION PRESERVATION TRUST LIMITED at THE COLEVIEW COMMUNITY CENTRE, STRATTON ST. MARGARET on WEDNESDAY, 11th JULY 1996 by TREVOR COCKBILL a Founder Member of the Trust; Former Member of the Mechanics' Institution and author of several works on the History of Swindon and District - PUBLISHED BY THE NEW MECHANICS' INSTITUTION PRESERVATION TRUST LIMITED SWINDON, 1997 NEW MECHANICS' INSTITUTION PRESERVATION TRUST LIMITED First Published 1997 Copyright © Christopher Peter Brett and Trevor William Cockbill; 1997 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright holders. ISBN applied for FOREWORD This little production is the first of what we hope will be a series of publications of particular appeal to members and supporters of the New Mechanics' Institution Preservation Trust Limited, and also to others interested in the history and heritage of Swindon and district. The text of "This is our Heritage" was not originally prepared with publication in mind, but as the draft for an address given to Trust supporters by one of our founder members at a meeting held on llth July 1996. -

In PDF Format

Gloucestershire Local History Association Speakers List May 2021 Please send all requests to be included in the list or updates to existing entries to [email protected] or write to Dr Ray Wilson, Oak House, Hamshill, Coaley, Dursley GL11 5EH The most recent copy of this list is available at www.gloshistory.org.uk/speakers.php Please Note: The inclusion of any speaker in this list does not imply any form of recommendation by the Gloucestershire Local History Association. Speaker's Name Contact details Topic Fee / other notes Virginia and David Adsett 18 Carisbrooke Drive We call ourselves 'Those were the Days' and have collections of iconic household objects, £30 plus 40p per mile 'Those were the Days' Cheltenham toys, accessories and costume from different decades that we bring out to groups. Our talks GL52 6YA are very much object based and bring back memories of past eras. 1. The Fighting 40s 01242 525270 2. The Fab 50s [email protected] 3. The Swinging 60s 4. Children's Hour 5. A woman's work is never done David H Aldred BSc Econ. MA PGCE 98 Malleson Road 1. History of Cleeve Hill, Cheltenham £50 including reasonable travel Gotherington 2. Winchcombe & its lost abbey expenses Cheltenham 3. Deserted medieval settlements in the North Cotswolds GL52 9EY 4. Hailes Abbey & the Mystery of the Holy Blood 5. Lost railway journeys in Gloucestershire 01242 672533 6. Place-names in the North Gloucestershire landscape [email protected] All talks illustrated with PowerPoint except (3) which is with slides Philip Ashford Severnview Cottage 1. -

The Fairford Flyer Back of the Grocer's Shop by an Oil Storage Tank

FAIRFORD HISTORY Fairford's engine remained on site until daybreak and buildings smouldered for a couple of days. It was thought that the fire started in the The Fairford Flyer back of the grocer's shop by an oil storage tank. A decision had been Newsletter No 20 made to install hydrants in Lechlade several years before the war but to- date only one had been installed; the absence of a telephone in the SOCIETY January 2015 police station and fire station also received unfavourable comments in the local press. The cause of the fire is unknown, but it is understood that the FAIRFORD FIRE ENGINE TO THE RESCUE –100 yrs ago premises involved were covered by insurance. On the night of Saturday 10 JUNE MEETS JULIA January 1915 a fire broke out No, this isn’t a title of a forthcoming novel, but thanks to the dedicated in the row of shops along work and efforts of Alison, the backbone of our outstanding Fairford Burford Road, Lechlade. The History Society, this is a short tale of a long trail to learn more about shops belonged to Messrs Sarah Thomas, the Baptists Minister’s daughter whose diaries of 1860-65 Cullerne and Co., grocers and I transcribed, edited and published over twenty years ago. butchers, and the Misses Despite several appeals through major newspapers and a dramatized Edmonds and Co., drapers version of the book produced as a Radio Four play in 1998, there was etc. and the auctioneers' office just no response from any member of the family. That is, until a couple of was the property of Innocent months ago when Julia Holt contacted Alison, having seen our Society and Sons. -

BIRTH of the FIRST: AUTHENTICITY and the COLLECTING of MODERN FIRST EDITIONS, 1890-1930 Madeleine Myfanwy Thompson Submitted To

BIRTH OF THE FIRST: AUTHENTICITY AND THE COLLECTING OF MODERN FIRST EDITIONS, 1890-1930 Madeleine Myfanwy Thompson Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English, Indiana University July 2013 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _______________________________ Christoph Irmscher, PhD _______________________________ Joel Silver, JD, MLS _______________________________ Paul Gutjahr, PhD _______________________________ Joss Marsh, PhD 24 May 2013 ii Copyright © 2013 Madeleine Myfanwy Thompson iii Acknowledgements One of the best things about finishing my dissertation is the opportunity to record my gratitude to those who have supported me over its course. Many librarians have provided me valuable assistance with reference requests during the past few years; among them include staff at New York Public Library’s Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, NYPL’s Rare Book Division, the Grolier Club Library, and The Lilly Library at Indiana University. I am especially indebted to The Lilly’s Public Services staff, who not only helped me to track down materials I needed but also provided me constant models of good librarianship. Additionally, I am grateful to the Bibliographical Society of America for a 2011 Katharine Pantzer Fellowship in the British Book Trades, which allowed me the opportunity to return to The Lilly Library to research the history of Elkin Mathews, Ltd. for my fourth chapter. I feel fortunate to be part of a family of writers and readers, and for their support, advice, and commiseration during the hardest parts of this project I am grateful to Anne Edwards Thompson, Gene Cohen, Clay Thompson, and especially to my sister, Elizabeth Thompson.