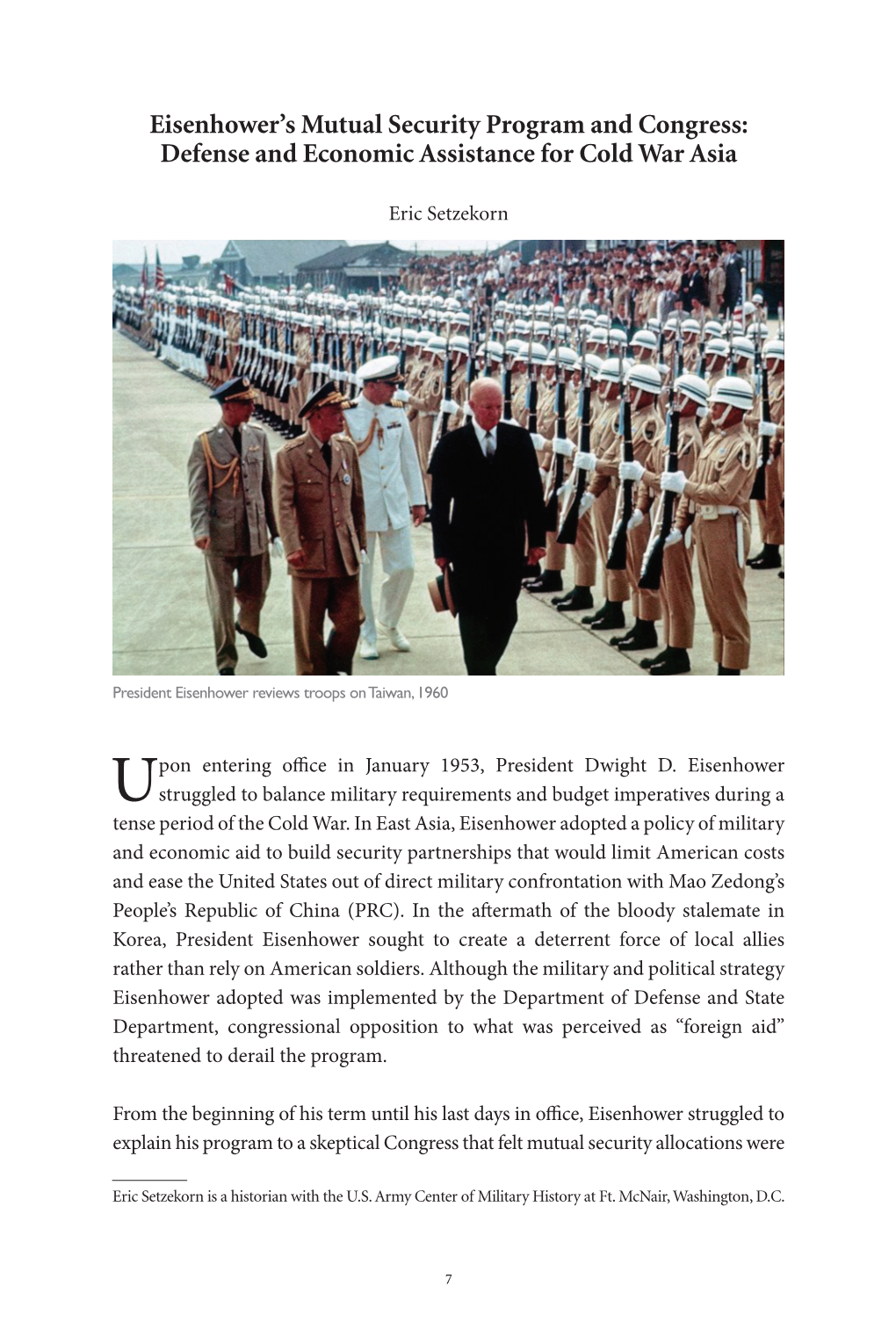

Eisenhower's Mutual Security Program and Congress: Defense

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 20, NOTE

PRINCIPAL OFFICIALS in the V.XECUTIVE BRANCH Appointed January 20 - April 20, 1953 NOTE: This list is limited to appointments made after January 20, 1953. Names con- tained herein replace corre- sponding names appearing in the 1952-53 U.S. Government Organization Manual. Federal Register Division National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington 25, D. C. MEMBERS OF THE CABINET TEE PRESIDENT John Foster Dulles, of New York, Secretary of State. President of the United States.-- Dwight D. Eisenhower George M. Humphrey, of Ohio, Secre- tary of the Treasury. EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT Charles Erwin Wilson, of Michigan, Secretary of Defense. The White House Office Herbert Brownell, Jr., of New York, 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW. Attorney General. NAtional 8-1414 Arthur E. Summerfield, of Michigan, The Assistant to the President.-- Postmaster General. Sherman Adams Assistant to The Assistant to the Douglas McKay, of Oregon, Secretary President.--Maxwell M. Rabb of the Interior. Special Assistant to The Assistant to the President.--Roger Steffan Ezra Taft Benson, of Utah, Secretary Special Assistant to The Assistant of Agriculture. to the President.--Charles F. Willis, Jr. Sinclair Weeks, of Massachusetts, Special Assistants in the White Secretary of Commerce Haase Office: L. Arthur Minnich, Jr. Martin P. Durkin, of Maryland, James M. Lambie Secretary of Labor. Special Counsel to the President (Acting Secretary).--Thomas E. Mrs. Oveta Culp Hobby, of Texas, Stephens Secretary of Health, Education, Secretary to the President (Press).-- and Welfare James C. Hagerty Assistant Press Secretary.--Murray Snyder Acting Special Counsel to the Presi- For sale by the dent.--Bernard M. -

Security Assistance

AN AUSA SPECIAL REPORT JUNE 1990 SECURITY ASSISTANCE: AN INSTRUMENT OF U.S. FOREIGN POLICY CONTENTS Page FOREWORD ...................................................................................................................................... i GLOSSARY ...................................................................................................................................... ii INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. I FOUNDATIONS OF SECURITY ASSISTANCE ...................................................................... .....1 EVOLUTION OF THE FOREIGN MILITARY FINANCING PROGRAM .................................. 2 OTHER MAJOR SECURITY ASSISTANCE PROGRAMS ......................................................... .4 U.S. FOREIGN MILITARY SALES ................... ......... ....................................................... ............. 5 DIRECT COMMERCIAL SALES ........................... ..................................................... ................... 6 U.S. INTERESTS AND THE PURPOSES OF THE SECURITY ASSISTANCE PROGRAM ...................................................... .......................... 6 PRINCIPAL U.S. GOVERNMENT AGENCIES INVOLVED IN SECURITY ASSISTANCE ........... .................................................................................... 8 SECURITY ASSISTANCE OPERATIONS ........................................................... ....................... I 1 BENEFITS AND COSTS OF THE -

Security Assistance and Cooperation: Shared Responsibility of the Departments of State and Defense

Security Assistance and Cooperation: Shared Responsibility of the Departments of State and Defense Nina M. Serafino Specialist in International Security Affairs May 26, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R44444 Security Assistance and Cooperation Shared Responsibility Summary The Department of State and the Department of Defense (DOD) have long shared responsibility for U.S. assistance to train, equip, and otherwise engage with foreign military and other security forces. The legal framework for such assistance emerged soon after World War II, when Congress charged the Secretary of State with responsibility for overseeing and providing general direction for military and other security assistance programs and the Secretary of Defense with responsibility for administering such programs. Over the years, congressional directives and executive actions have modified, shaped, and refined State Department and DOD roles and responsibilities. Changes in the legal framework through which security assistance to foreign forces—weapons, training, lethal and nonlethal military assistance, and military education and training—is provided have responded to a wide array of factors. Legal Authorization and Funding For most of the past half-century, Congress has authorized U.S. security assistance programs through Title 22 of the U.S. Code (Foreign Relations) and appropriated the bulk of security assistance funds through State Department accounts. DOD administers programs funded through several of these accounts under the Secretary of State’s direction and oversight. Beginning in the 1980s, however, and increasingly after the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001 (9/11), some policymakers have come to view the State Department authorities, or the funding allocated to them, as insufficient and too inflexible to respond to evolving and emerging security threats. -

Download Full Book

Trade and Aid Kaufman, Burton I. Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Kaufman, Burton I. Trade and Aid: Eisenhower's Foreign Economic Policy, 1953-1961. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.71585. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/71585 [ Access provided at 24 Sep 2021 09:44 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Kaufman HOPKINS OPEN PUBLISHING ENCORE EDITIONS Trade and Aid Trade Burton I. Kaufman ISBN : ---- ISBN : --- Open access edition supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Trade and Aid Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. 9 781421 435725 Cover design: Jennifer Corr Paulson Eisenhower’s Foreign Economic Policy, 1953–1961 Cover illustration: Strawberry Blossom Open access edition supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. © 2019 Johns Hopkins University Press Published 2019 Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. CC BY-NC-ND ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3574-9 (open access) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3574-8 (open access) ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3572-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3572-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3573-2 (electronic) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3573-X (electronic) This page supersedes the copyright page included in the original publication of this work. -

![Papers of W. Averell Harriman [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3626/papers-of-w-averell-harriman-finding-aid-library-of-congress-2863626.webp)

Papers of W. Averell Harriman [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress

W. Averell Harriman A Register of His Papers in the Library of Congress Prepared by Allan Teichroew with the assistance of Haley Barnett, Connie L. Cartledge, Paul Colton, Marie Friendly, Patrick Holyfield, Allyson H. Jackson, Patrick Kerwin, Mary A. Lacy, Sherralyn McCoy, John R. Monagle, Susie H. Moody, Sheri Shepherd, and Thelma Queen Revised by Connie L. Cartledge with the assistance of Karen Stuart Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2001 Contact information: http://lcweb.loc.gov/rr/mss/address.html Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2003 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms003012 Latest revision: 2008 July Collection Summary Title: Papers of W. Averell Harriman Span Dates: 1869-1988 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1895-1986) ID No.: MSS61911 Creator: Harriman, W. Averell (William Averell), 1891-1986 Extent: 344,250 items; 1,108 containers plus 11 classified; 526.3 linear feet; 54 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in English Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: Diplomat, entrepreneur, philanthropist, and politician. Correspondence, memoranda, family papers, business records, diplomatic accounts, speeches, statements and writings, photographs, and other papers documenting Harriman's career in business, finance, politics, and public service, particularly during the Franklin Roosevelt, Truman, Kennedy, Johnson, and Carter presidential administrations. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. Personal Names Abel, Elie. Acheson, Dean, 1893-1971. -

Front Cover.P65

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of RESEARCH COLLECTIONS IN AMERICAN POLITICS Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editor: William E. Leuchtenburg The Confidential File of the Eisenhower White House, 1953–1961 Part 3: Departments and Agencies A UPA Collection from Cover: Portrait courtesy of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Library. RESEARCH COLLECTIONS IN AMERICAN POLITICS Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editor: William E. Leuchtenburg The Confidential File of the Eisenhower White House, 1953–1961 Part 3: Departments and Agencies Project Editor Robert E. Lester Guide compiled by Carrie B. Vivian A UPA Collection from 7500 Old Georgetown Road • Bethesda, MD 20814-6126 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The confidential file of the Eisenhower White House, 1953–1961 [microform] / project editor, Robert E. Lester. microfilm reels. — (Research collections in American politics) “The documents reproduced in this publication are from the Papers of Dwight D. Eisenhower in the custody of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Library, National Archives and Records Administration. Former President Eisenhower donated his literary rights in these documents to the public.” Includes index. Contents: pt. 1. Confidential subject files—pt. 2. Presidential trips and conferences— pt. 3. Departments and agencies. ISBN 1-55655-959-3 (pt. 1) — ISBN 0-88692-630-0 (pt. 2) — ISBN 0-88692-648-3 (pt. 3) 1. United States—Politics and government—1953–1961—Sources. 2. United States—Foreign relations—1953–1961—Sources. 3. Dwight D. Eisenhower Library—Archives. I. Lester, Robert. II. United States. National Archives and Records Administration. III. LexisNexis (Firm) IV. Series. E835 973.921—dc22 2004046529 CIP Copyright © 2005 LexisNexis, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. -

The Marshall Plan: Design, Accomplishments, and Significance

The Marshall Plan: Design, Accomplishments, and Significance Curt Tarnoff Specialist in Foreign Affairs January 18, 2018 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R45079 The Marshall Plan: Design, Accomplishments, and Historic Significance Summary The European Recovery Program (ERP), more commonly known as the Marshall Plan (the Plan), was a program of U.S. assistance to Europe during the period 1948-1951. The Marshall Plan— launched in a speech delivered by Secretary of State George Marshall on June 5, 1947—is considered by many to have been the most effective ever of U.S. foreign aid programs. An effort to prevent the economic deterioration of postwar Europe, expansion of communism, and stagnation of world trade, the Plan sought to stimulate European production, promote adoption of policies leading to stable economies, and take measures to increase trade among European countries and between Europe and the rest of the world. Since its conclusion, some Members of Congress and others have periodically recommended establishment of new “Marshall Plans”—for Central America, Eastern Europe, sub-Saharan Africa, and elsewhere. Design. The Marshall Plan was a joint effort between the United States and Europe and among European nations working together. Prior to formulation of a program of assistance, the United States required that European nations agree on a financial proposal, including a plan of action committing Europe to take steps toward solving its economic problems. The Truman Administration and Congress worked together to formulate the European Recovery Program, which eventually provided roughly $13.3 billion ($143 billion in 2017 dollars) of assistance to 16 countries. -

Foreign Aid Legislation Time for a New Look Michael H

Cornell Law Review Volume 38 Article 2 Issue 2 Winter 1953 Foreign Aid Legislation Time for a New Look Michael H. Cardozo Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael H. Cardozo, Foreign Aid Legislation Time for a New Look , 38 Cornell L. Rev. 161 (1953) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol38/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOREIGN AID LEGISLATION: TIME FOR A NEW LOOK Michael H. Cardozo* The misnomer "foreign aid" is what we call those measures whereby the United States helps itself by helping others.1 Their constitutional sanction is the same as for social security and arms for our military forces, namely, the power to spend funds of the Treasury to "provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States."2 The statutory prototype is the wartime Lend-Lease Act,3 appropriately described in the heading as "An act to promote the defense of the United States." In every year since the end of World War II Congress has responded to the needs of a disrupted world with at least one new "foreign aid" act. Each one has authorized the use of funds of the U. S. Treasury to pay for goods and services needed by specified friends and allies around the globe who could not pay in foreign exchange. -

The Marshall Plan: Design, Accomplishments, and Relevance to the Present

Order Code 97-62 F CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web The Marshall Plan: Design, Accomplishments, and Relevance to the Present January 6, 1997 Curt Tarnoff Specialist in Foreign Affairs Foreign Affairs and National Defense Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress The Marshall Plan: Design, Accomplishments, and Relevance to the Present Summary Periodically, Members of Congress and others have recommended establishment of a ‘Marshall Plan’ for Central America, Eastern Europe, the former Soviet Union, and elsewhere. They do so largely because the original Marshall Plan, a program of U.S. assistance to Europe during the period 1948-1951, is considered by many to have been the most effective ever of U.S. foreign aid programs. An effort to prevent the economic deterioration of Europe, expansion of communism, and stagnation of world trade, the Plan sought to stimulate European production, promote adoption of policies leading to stable economies, and take measures to increase trade among European countries and between Europe and the rest of the world. The Plan was a joint effort between the United States and Europe and among European nations working together. Prior to formulation of a program of assistance, the United States required that European nations agree on a financial proposal, including a plan of action committing Europe to take steps toward solution of its economic problems. The Truman Administration and the Congress worked together to formulate the European Recovery Program, which eventually provided roughly $13.3 billion of assistance to 16 countries. Two agencies implemented the program, the U.S. Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA) and the European-run Organization for European Economic Cooperation. -

The Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan The Lessons Learned for the 21st Century There are not many of us left who served through the Marshall Plan from its beginning, and fewer still who served time in the Hotel Talleyrand in Paris, the site of the anniversary celebration, in June 2007, of Marshall Plan Secretary George C. Marshall’s 1947 commencement address launching the European Recovery Program. There are, though, scholars who can address those times and evaluate them so that the experience can live on. The dedication of the Hotel de Talleyrand as a memorial to that unique enterprise provided the opportunity; The Marshall Plan and the analyses and evaluations in this splendid volume, The Marshall Plan: Lessons Learned for the 21st Century, refl ect the excitement, as well as the accomplishments, of an economic enterprise that produced the infrastructure of NATO and the European Union. Long live the spirit of Marshall’s vision! Lessons Learned Thomas C. Schelling, Marshall Plan alumnus, Washington, for the 21st Century Copenhagen, Paris, Washington, ’48-‘53, Nobel Prize in Economics 2005 Lessons Learned for the 21 A historical event is and remains crucial when it does interact with others in such a way as to contribute to a deep and positive change in the course of history. In this sense, the Marshall Plan made an outstanding and lasting contribution. It was instrumental to overcoming the temptation of isolationism in the US, to reviving our badly needed economic recovery and gave a decisive input to coordinating our national efforts, thus paving the way to our future European integration. -

Security Assistance: Adapting to the Post-Cold War Era

. .·. ·. ' . · . Associ tion .· · . � oftbe, Unite�. States.. Army ·; . :. I '; . .· · . ' . • ... ·' . '. · . • . � . • . ' ' . .. i • • ' . ·. ' ·' .• .,i - ... · . : . SECURITY ASSISTAN:CE:. ._ . ·._ . , ,· . · . ADAPTING TO THE. POST-COLD WA� ERA .: .. • ,. • . '· .. , • • • • J • · · • . : . ' · • . ..' . .. ' . ·· : . ' ·' .. ' · . · .. _September 1996 .·· . ·.. ,_. ' ' . '..· ... I ·, · . · ·:. · . :-. · . · Institute. of. Land. .Warfare · . · •. .. ··.· SECURITY ASSISTANCE: ADAPTING TO THE POST-COLD WAR ERA CONTENTS FOREWORD................................................................................................................................................ v SECURITY ASSISTANCE: ADAPTING TO THE POST-C OLD WAR ERA ......................................... 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 1 Fiscal Year 1997 Program ........................... ..................................................................................... 1 SECURITY ASSISTANCE ................................................... ......................................................... ....... 2 Program Evolution ............................................................................................................................. 3 Foreign Military Financing (FMF)..................................................................................................... 3 International Military Education and Training (IMET).............................................................. -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Foreign Assistance Series

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Foreign Assistance Series MELBOURNE L. SPECTOR Interviewed by: W. Haven North Initial interview date: September 12, 1996 Copyright 1998 ADST The oral history program was made possible through support provided by the Center for Development Information and Evaluation, U.S. Agency for International Development, under terms of Cooperative Agreement No. AEP-0085-A-00-5026-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the interviewee and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for International Development or the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. TABLE OF CONTENTS Early years and education Working in the United Pueblos Agency 1941 Assignment with the War Relocation Authority 1941 Drafted into the Army / Air Force headquarters and the UNRRA overseas 1945 Position with State Department Personnel Office 1948 Personnel work for ECA 1948 Assignment with ECA in Paris 1949-1951 Back to Washington as ECA Deputy Director of Personnel and FOA, then MSA 1951-1954 Creation of the Foreign Operations Administration 1953 Assignment to the FOA mission in Mexico 1954-1959 Assignment to ICA's Office of Mexico, Central America and Caribbean Affairs 1959-1961 ICA organization 1 The beginning of AID 1961 Appointment as Director of Personnel of the new agency, AID 1961 Return to the State Department as Executive Director, Latin America Bureau 1962 Special assignment in AID on Latin America 1963 Special assignment as Counselor for Administration,