Verse and Lore: ‗Poems on History' (Yongshi Shi) from the Selections of Refined Literature (Wen Xuan)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medicine Buddha Sutra

Medicine Buddha Sutra 藥師琉璃光如來本願功德經 Fo Guang Shan International Translation Center b c © 2002, 2005 Buddha’s Light Publishing © 2015 Fo Guang Shan International Translation Center Table of Contents Published by the Fo Guang Shan International Translation Center 3456 Glenmark Drive Hacienda Heights, CA 91745 U.S.A. Tel: (626) 330-8361 / (626) 330-8362 Incense Praise 3 Fax: (626) 330-8363 www.fgsitc.org Sutra Opening Verse 5 Protected by copyright under the terms of the International Copyright Medicine Buddha Sutra 7 Union; all rights reserved. Except for fair use in book reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced for any reason by any means, including any method of photographic reproduction, without permission of the publisher. Triple Refuge 137 Printed in Taiwan. Dedication of Merit 139 A Paryer to Medicine Buddha 141 2 3 Lu Xiang Zan 爐 香 讚 Incense Praise Lu Xiang Zha Ruo Incense burning in the censer, 爐 香 乍 爇 Fa Jie Meng Xun All space permeated with fragrance. 法 界 蒙 熏 Zhu Fo Hai Hui Xi Yao Wen The Buddhas perceive it from every direction, 諸 佛 海 會 悉 遙 聞 Sui Chu Jie Xiang Yun Auspicious clouds gather everywhere. 隨 處 結 祥 雲 With our sincerity, Cheng Yi Fang Yin 誠 意 方 殷 The Buddhas manifest themselves in their entirety. Zhu Fo Xian Quan Shen 諸 佛 現 全 身 Nan Mo Xiang Yun Gai Pu Sa 南 無 香 雲 蓋 菩 薩 Mo He Sa We take refuge in the Bodhisattvas-Mahasattvas. 摩 訶 薩 4 5 Kai Jing Ji 開 經 偈 Sutra Opening Verse Wu Shang Shen Shen Wei Miao Fa 無 上 甚 深 微 妙 法 The unexcelled, most profound, and exquisitely Bai Qian Wan Jie Nan Zao Yu wondrous Dharma, 百 千 萬 劫 難 遭 遇 Is difficult to encounter throughout hundreds of Wo Jin Jian Wen De Shou Chi thousands of millions of kalpas. -

Characteristics of Chinese Poetic-Musical Creations

Characteristics of Chinese Poetic-Musical Creations Yan GENG1 Abstract: The present study intoduces a series of characteristics related to Chinese poetry. It shows that, together with rhythmical structure and intonation (which has a crucial role in conveying meaning), an additional, fundamental aspect of Chinese poetry lies in the latent, pictorial effect of the writing. Various genres and forms of Chinese poetry are touched upon, as well as a series of figures of speech, themes (nature, love, sadness, mythology etc.) and symbols (particularly of vegetal and animal origin), which are frequently encountered in the poems. Key-words: rhythm, intonation, system of tones, rhyme, system of writing, figures of speech 1. Introduction In his Advanced Music Theory course, &RQVWDQWLQ 5kSă VKRZV WKDW ³we can differentiate between two levels of the phenomenon of rhythm: the first, a general philosophical one, meaning, within the context of music, the ensemble of movements perceived, thus the macrostructural level; the second, the micro-VWUXFWXUH ZKHUH UK\WKP PHDQV GXUDWLRQV « LQWHQVLWLHVDQGWHPSR « 0RUHRYHUZHFDQVD\WKDWUK\WKPGRHVQRWH[LVWEXWUDWKHUMXVW the succession of sounds in time [does].´2 Studies on rhythm, carried out by ethno- musicology researchers, can guide us to its genesis. A first fact that these studies point towards is the indissoluble unity of the birth process of artistic creation: poetry, music (rhythm-melody) and dance, which manifested syncretically for a very lengthy period of time. These aspects are not singular or characteristic for just one culture, as it appears that they have manifested everywhere from the very beginning of mankind. There is proof both in Chinese culture, as well as in ancient Romanian culture, that certifies the existence of a syncretic development of the arts and language. -

The Reception and Translation of Classical Chinese Poetry in English

NCUE Journal of Humanities Vol. 6, pp. 47-64 September, 2012 The Reception and Translation of Classical Chinese Poetry in English Chia-hui Liao∗ Abstract Translation and reception are inseparable. Translation helps disseminate foreign literature in the target system. An evident example is Ezra Pound’s translation based on the 8th-century Chinese poet Li Bo’s “The River-Merchant’s Wife,” which has been anthologised in Anglophone literature. Through a diachronic survey of the translation of classical Chinese poetry in English, the current paper places emphasis on the interaction between the translation and the target socio-cultural context. It attempts to stress that translation occurs in a context—a translated work is not autonomous and isolated from the literary, cultural, social, and political activities of the receiving end. Keywords: poetry translation, context, reception, target system, publishing phenomenon ∗ Adjunct Lecturer, Department of English, National Changhua University of Education. Received December 30, 2011; accepted March 21, 2012; last revised May 13, 2012. 47 國立彰化師範大學文學院學報 第六期,頁 47-64 二○一二年九月 中詩英譯與接受現象 廖佳慧∗ 摘要 研究翻譯作品,必得研究其在譯入環境中的接受反應。透過翻譯,外國文學在 目的系統中廣宣流布。龐德的〈河商之妻〉(譯寫自李白的〈長干行〉)即一代表實 例,至今仍被納入英美文學選集中。藉由中詩英譯的歷時調查,本文側重譯作與譯 入文境間的互動,審視前者與後者的社會文化間的關係。本文強調翻譯行為的發生 與接受一方的時代背景相互作用。譯作不會憑空出現,亦不會在目的環境中形成封 閉的狀態,而是與文學、文化、社會與政治等活動彼此交流、影響。 關鍵字:詩詞翻譯、文境、接受反應、目的/譯入系統、出版現象 ∗ 國立彰化師範大學英語系兼任講師。 到稿日期:2011 年 12 月 30 日;確定刊登日期:2012 年 3 月 21 日;最後修訂日期:2012 年 5 月 13 日。 48 The Reception and Translation of Classical Chinese Poetry in English Writing does not happen in a vacuum, it happens in a context and the process of translating texts form one cultural system into another is not a neutral, innocent, transparent activity. -

The History and Politics of Taiwan's February 28

The History and Politics of Taiwan’s February 28 Incident, 1947- 2008 by Yen-Kuang Kuo BA, National Taiwan Univeristy, Taiwan, 1991 BA, University of Victoria, 2007 MA, University of Victoria, 2009 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of History © Yen-Kuang Kuo, 2020 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee The History and Politics of Taiwan’s February 28 Incident, 1947- 2008 by Yen-Kuang Kuo BA, National Taiwan Univeristy, Taiwan, 1991 BA, University of Victoria, 2007 MA, University of Victoria, 2009 Supervisory Committee Dr. Zhongping Chen, Supervisor Department of History Dr. Gregory Blue, Departmental Member Department of History Dr. John Price, Departmental Member Department of History Dr. Andrew Marton, Outside Member Department of Pacific and Asian Studies iii Abstract Taiwan’s February 28 Incident happened in 1947 as a set of popular protests against the postwar policies of the Nationalist Party, and it then sparked militant actions and political struggles of Taiwanese but ended with military suppression and political persecution by the Nanjing government. The Nationalist Party first defined the Incident as a rebellion by pro-Japanese forces and communist saboteurs. As the enemy of the Nationalist Party in China’s Civil War (1946-1949), the Chinese Communist Party initially interpreted the Incident as a Taiwanese fight for political autonomy in the party’s wartime propaganda, and then reinterpreted the event as an anti-Nationalist uprising under its own leadership. -

Download (3MB)

Lipsey, Eleanor Laura (2018) Music motifs in Six Dynasties texts. PhD thesis. SOAS University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/32199 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Music motifs in Six Dynasties texts Eleanor Laura Lipsey Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 2018 Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures China & Inner Asia Section SOAS, University of London 1 Abstract This is a study of the music culture of the Six Dynasties era (220–589 CE), as represented in certain texts of the period, to uncover clues to the music culture that can be found in textual references to music. This study diverges from most scholarship on Six Dynasties music culture in four major ways. The first concerns the type of text examined: since the standard histories have been extensively researched, I work with other types of literature. The second is the casual and indirect nature of the references to music that I analyze: particularly when the focus of research is on ideas, most scholarship is directed at formal essays that explicitly address questions about the nature of music. -

Han, Wei, Six Dynasties Syllabus

Topics in Classical Chinese Poetry and Poetics (16:217:527) Han, Wei and Six Dynasties Course Guidelines and Syllabus Spring 2020 Instructor: Professor Wendy Swartz [email protected] Scott Hall 323 Office Hour: T 11:00-12:00, and by appointment Course Description: This course introduces the major poetic genres and works of the Han, Wei and Six Dynasties, the formative period for classical poetry. It will focus primarily on the art of reading poetry, with attention to relevant historical, biographical and literary-historical contexts. Emphasis will thus be placed on 1) learning the conventions of particular genres and subgenres, 2) assessing the qualities of individual poets and poems through an examination of their manipulation of these conventions, and a comparison with other voices in the tradition, and 3) recognizing the larger stylistic shifts and literary concerns that developed over the course of early medieval China. Readings from a selection of modern criticism will be helpful for understanding individual poets, issues and themes. Primary texts and commentaries are in Chinese, therefore proficiency in reading both modern and classical Chinese is required. Requirements and Grading: 1. Participation (10%): Participation in the translation and analysis of poems in class is mandatory. Students will need to come to class having read and translated all of the assigned poems and critical literature. 2. Class presentation (20%): Each week a student will be delegated to present on the weekly secondary readings (highlighted in bold). These brief presentations should summarize and analyze the main arguments of the readings and pose questions about them. All other students will read in advance the selected material and be ready to pose questions about the reading. -

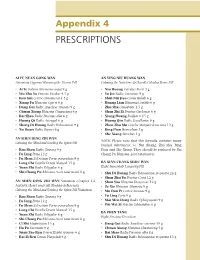

Appendix 4 PRESCRIPTIONS

Appendix 4 PRESCRIPTIONS AI FU NUAN GONG WAN AN YING NIU HUANG WAN Artemisia-Cyperus Warming the Uterus Pill Calming the Nutritive-Qi [Level] Calculus Bovis Pill • Ai Ye Folium Artemisiae argyi 9 g • Niu Huang Calculus Bovis 3 g • Wu Zhu Yu Fructus Evodiae 4.5 g • Yu Jin Radix Curcumae 9 g • Rou Gui Cortex Cinnamomi 4.5 g • Shui Niu Jiao Cornu Bubali 6 g • Xiang Fu Rhizoma Cyperi 9 g • Huang Lian Rhizoma Coptidis 6 g • Dang Gui Radix Angelicae sinensis 9 g • Zhu Sha Cinnabaris 1.5 g • Chuan Xiong Rhizoma Chuanxiong 6 g • Shan Zhi Zi Fructus Gardeniae 6 g • Bai Shao Radix Paeoniae alba 6 g • Xiong Huang Realgar 0.15 g • Huang Qi Radix Astragali 6 g • Huang Qin Radix Scutellariae 9 g • Sheng Di Huang Radix Rehmanniae 9 g • Zhen Zhu Mu Concha Margatiriferae usta 12 g • Xu Duan Radix Dipsaci 6 g • Bing Pian Borneolum 3 g • She Xiang Moschus 1 g AN SHEN DING ZHI WAN NOTE: Please note that this formula contains many Calming the Mind and Settling the Spirit Pill banned substances, i.e. Niu Huang, Zhu Sha, Bing • Ren Shen Radix Ginseng 9 g Pian and She Xiang. They should be replaced by Shi • Fu Ling Poria 12 g Chang Pu Rhizoma Acori tatarinowii. • Fu Shen Sclerotium Poriae pararadicis 9 g • Long Chi Fossilia Dentis Mastodi 15 g BA XIAN CHANG SHOU WAN • Yuan Zhi Radix Polygalae 6 g Eight Immortals Longevity Pill • Shi Chang Pu Rhizoma Acori tatarinowii 8 g • Shu Di Huang Radix Rehmanniae preparata 24 g • Shan Zhu Yu Fructus Corni 12 g AN SHEN DING ZHI WAN Variation (Chapter 14, • Shan Yao Rhizoma Dioscoreae 12 g Anxiety, Heart and Gall Bladder -

340336 1 En Bookbackmatter 251..302

A List of Historical Texts 《安禄山事迹》 《楚辭 Á 招魂》 《楚辭注》 《打馬》 《打馬格》 《打馬錄》 《打馬圖經》 《打馬圖示》 《打馬圖序》 《大錢圖錄》 《道教援神契》 《冬月洛城北謁玄元皇帝廟》 《風俗通義 Á 正失》 《佛说七千佛神符經》 《宮詞》 《古博經》 《古今圖書集成》 《古泉匯》 《古事記》 《韓非子 Á 外儲說左上》 《韓非子》 《漢書 Á 武帝記》 《漢書 Á 遊俠傳》 《和漢古今泉貨鑒》 《後漢書 Á 許升婁傳》 《黃帝金匱》 《黃神越章》 《江南曲》 《金鑾密记》 《經國集》 《舊唐書 Á 玄宗本紀》 《舊唐書 Á 職官志 Á 三平准令條》 《開元別記》 © Springer Science+Business Media Singapore 2016 251 A.C. Fang and F. Thierry (eds.), The Language and Iconography of Chinese Charms, DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-1793-3 252 A List of Historical Texts 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷二 Á 戲擲金錢》 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷三》 《雷霆咒》 《類編長安志》 《歷代錢譜》 《歷代泉譜》 《歷代神仙通鑑》 《聊斋志異》 《遼史 Á 兵衛志》 《六甲祕祝》 《六甲通靈符》 《六甲陰陽符》 《論語 Á 陽貨》 《曲江對雨》 《全唐詩 Á 卷八七五 Á 司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《泉志 Á 卷十五 Á 厭勝品》 《勸學詩》 《群書類叢》 《日本書紀》 《三教論衡》 《尚書》 《尚書考靈曜》 《神清咒》 《詩經》 《十二真君傳》 《史記 Á 宋微子世家 Á 第八》 《史記 Á 吳王濞列傳》 《事物绀珠》 《漱玉集》 《說苑 Á 正諫篇》 《司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《私教類聚》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十一 Á 志第一百四 Á 輿服三 Á 天子之服 皇太子附 后妃之 服 命婦附》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十二 Á 志第一百五 Á 輿服四 Á 諸臣服上》 《搜神記》 《太平洞極經》 《太平廣記》 《太平御覽》 《太上感應篇》 《太上咒》 《唐會要 Á 卷八十三 Á 嫁娶 Á 建中元年十一月十六日條》 《唐兩京城坊考 Á 卷三》 《唐六典 Á 卷二十 Á 左藏令務》 《天曹地府祭》 A List of Historical Texts 253 《天罡咒》 《通志》 《圖畫見聞志》 《退宮人》 《萬葉集》 《倭名类聚抄》 《五代會要 Á 卷二十九》 《五行大義》 《西京雜記 Á 卷下 Á 陸博術》 《仙人篇》 《新唐書 Á 食貨志》 《新撰陰陽書》 《續錢譜》 《續日本記》 《續資治通鑑》 《延喜式》 《顏氏家訓 Á 雜藝》 《鹽鐵論 Á 授時》 《易經 Á 泰》 《弈旨》 《玉芝堂談薈》 《元史 Á 卷七十八 Á 志第二十八 Á 輿服一 儀衛附》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 符圖部》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 三洞經教部》 《韻府帬玉》 《戰國策 Á 齊策》 《直齋書錄解題》 《周易》 《莊子 Á 天地》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二百一十六 Á 唐紀三十二 Á 玄宗八載》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二一六 Á 唐天寶十載》 A Chronology of Chinese Dynasties and Periods ca. -

The Arts of Making Do and Working out in Beijing, China

What are friends for?: The arts of making do and working out in Beijing, China Michelle Yang Zhang Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2020 © 2020 Michelle Yang Zhang All Rights Reserved Abstract What are friends for?: The arts of making do and working out in Beijing, China Michelle Yang Zhang Through a second look at the now twenty-five-year-old literature on guanxi, a form of reciprocal relationship making and using in China, I examine how the kinds of opportunities and challenges possible for young people intersect with who they know and how this has changed (with its own set of reflections on and consequences for a still-rapidly changing China) since China’s rural to urban transition. My dissertation project examines how young people in contemporary urban China form and produce guanxi ties (resource-full relationships) through the theoretical lens of practice and possibility, inspired by de Certeau’s conceptualization of practice, productive consumption, and strategies versus tactics (1984). Drawing on qualitative data gathered through participant observation and unstructured interviews, I sought to both describe and analyze when, where, and how social networks became consequential. Central to my methodology is an emphasis on people and their practices rather than the common sense categories used to describe them. The people in my field research were predominantly aged 18- 30 and came from a range of ethnic, professional, and education backgrounds. In so doing, I was able to examine the moments and contexts within which some people have opportunities and others do not, as well as when some are vulnerable while others are less so. -

Daoism and Daoist Art

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Daoism and Daoist Art Works of Art (19) Essay Indigenous to China, Daoism arose as a secular school of thought with a strong metaphysical foundation around 500 B.C., during a time when fundamental spiritual ideas were emerging in both the East and the West. Two core texts form the basis of Daoism: the Laozi and the Zhuangzi, attributed to the two eponymous masters, whose historical identity, like the circumstances surrounding the compilation of their texts, remains uncertain. The Laozi—also called the Daodejing, or Scripture of the Way and Virtue—has been understood as a set of instructions for virtuous rulership or for self- cultivation. It stresses the concept of nonaction or noninterference with the natural order of things. Dao, usually translated as the Way, may be understood as the path to achieving a state of enlightenment resulting in longevity or even immortality. But Dao, as something ineffable, shapeless, and conceived of as an infinite void, may also be understood as the unfathomable origin of the world and as the progenitor of the dualistic forces yin and yang. Yin, associated with shade, water, west, and the tiger, and yang, associated with light, fire, east, and the dragon, are the two alternating phases of cosmic energy; their dynamic balance brings cosmic harmony. Over time, Daoism developed into an organized religion—largely in response to the institutional structure of Buddhism—with an ever-growing canon of texts and pantheon of gods, and a significant number of schools with often distinctly different ideas and approaches. At times, some of these schools were also politically active. -

Download Article (PDF)

International Conference on Humanities and Social Science (HSS 2016) Studies on English Translation of Shijing in China: From Language to Culture 1 2,* Yan-Hua WANG and Pei-Xi HUANG 1Shanghai Technical Institute of Electronics and Technology, Fudan University, Fengxian District, Shanghai, China 2College of foreign languages,Donghua University, Shanghai, China *Corresponding author Keywords: Shijing, English translation, Cultural consciousness. Abstract.Studies on English translation of Shijing have undergone three phases in China. It begins with introductions of English versions and their translators as well as comparisons between them; the second phase features in the theoretical attempt of translational strategies. The first two phases stress more language or translation theories than cultures. The third is characterized by cross-cultural, interdisciplinary and multidimensional research on English translation of Shijing. Meanwhile, new translational theories and historical literature offer new perspectives for studies on English translation of Shijing, which enhances its cross-cultural research in the new era. Introduction English translation of Shijing can be dated back to the eighteenth century. It is believed that English translation of Shijing was initiated by Sir William Jones, a British orientalist and translator, who was interested in Chinese culture and attempted to translate some poems in Shijing into English.[1] His work marked the beginning of Shijing going into the English world and studies on it have been continuously carried on ever since. Compared with overseas research on the English translation of Shijing, its studies in China began much later. Recent literature reveals that most studies did not begin until 1980s. Chinese studies on English translation of Shijing can be divided into three phases: introduction of English versions and their translators in the first phrase, theoretical attempts in the second and cross-cultural, interdisciplinary and multidimensional studies in the third. -

The Seal of the Unity of the Three SAMPLE

!"# $#%& '( !"# )*+!, '( !"# !"-## By the same author: Great Clarity: Daoism and Alchemy in Early Medieval China (Stanford University Press, 2006) The Encyclopedia of Taoism, editor (Routledge, 2008) Awakening to Reality: The “Regulated Verses” of the Wuzhen pian, a Taoist Classic of Internal Alchemy (Golden Elixir Press, 2009) Fabrizio Pregadio The Seal of the Unity of the Three A Study and Translation of the Cantong qi, the Source of the Taoist Way of the Golden Elixir Golden Elixir Press This sample contains parts of the Introduction, translations of 9 of the 88 sections of the Cantong qi, and parts of the back matter. For other samples and more information visit this web page: www.goldenelixir.com/press/trl_02_ctq.html Golden Elixir Press, Mountain View, CA www.goldenelixir.com [email protected] © 2011 Fabrizio Pregadio ISBN 978-0-9843082-7-9 (cloth) ISBN 978-0-9843082-8-6 (paperback) All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Typeset in Sabon. Text area proportioned in the Golden Section. Cover: The Chinese character dan 丹 , “Elixir.” To Yoshiko Contents Preface, ix Introduction, 1 The Title of the Cantong qi, 2 A Single Author, or Multiple Authors?, 5 The Dating Riddle, 11 The Three Books and the “Ancient Text,” 28 Main Commentaries, 33 Dao, Cosmos, and Man, 36 The Way of “Non-Doing,” 47 Alchemy in the Cantong qi, 53 From the External Elixir to the Internal Elixir, 58 Translation, 65 Book 1, 69 Book 2, 92 Book 3, 114 Notes, 127 Textual Notes, 231 Tables and Figures, 245 Appendixes, 261 Two Biographies of Wei Boyang, 263 Chinese Text, 266 Index of Main Subjects, 286 Glossary of Chinese Characters, 295 Works Quoted, 303 www.goldenelixir.com/press/trl_02_ctq.html www.goldenelixir.com/press/trl_02_ctq.html Introduction “The Cantong qi is the forefather of the scriptures on the Elixir of all times.