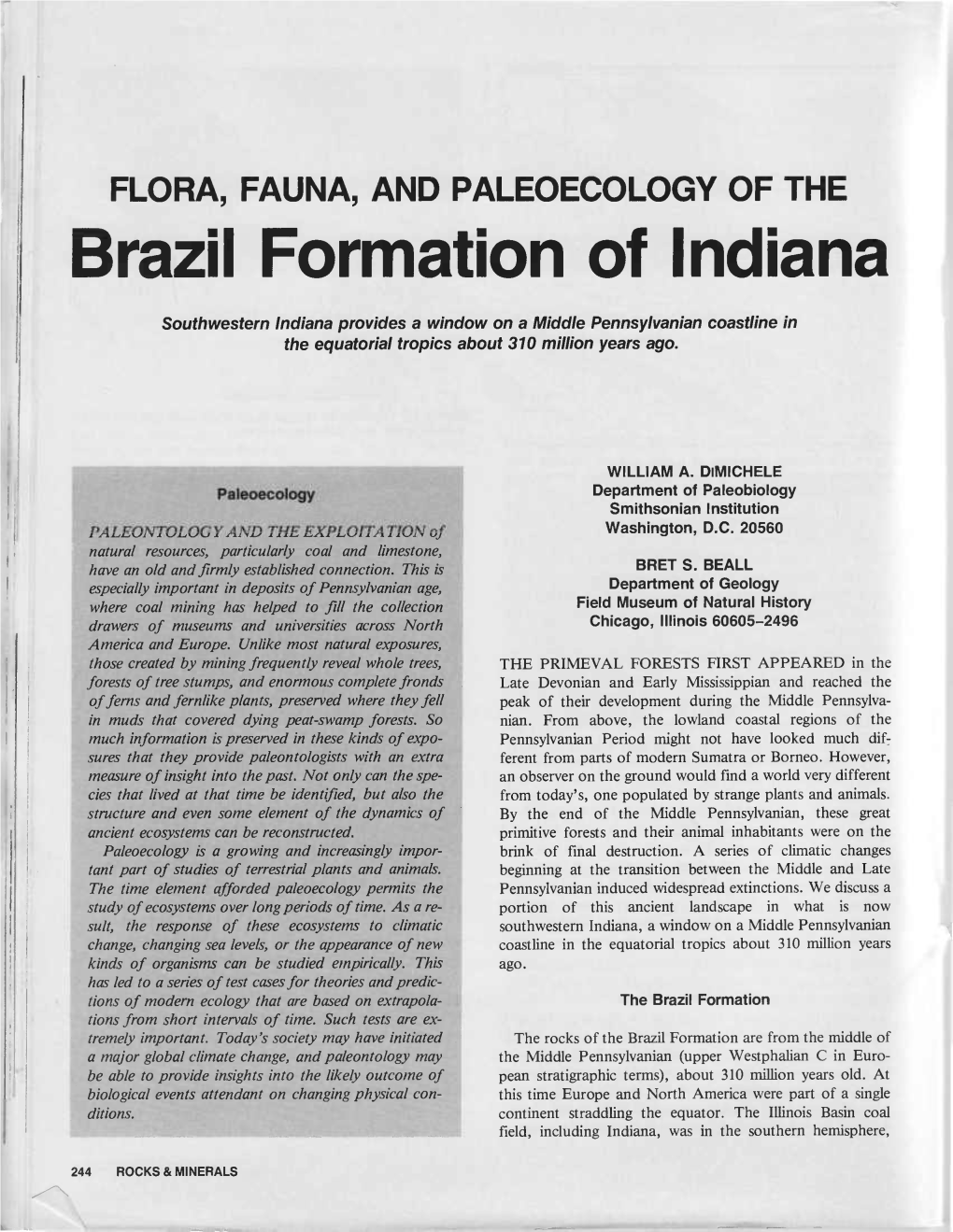

Brazil Formation of Indiana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONODONT BIOSTRATIGRAPHY and ... -.: Palaeontologia Polonica

CONODONT BIOSTRATIGRAPHY AND PALEOECOLOGY OF THE PERTH LIMESTONE MEMBER, STAUNTON FORMATION (PENNSYLVANIAN) OF THE ILLINOIS BASIN, U.S.A. CARl B. REXROAD. lEWIS M. BROWN. JOE DEVERA. and REBECCA J. SUMAN Rexroad , c.. Brown . L.. Devera, 1.. and Suman, R. 1998. Conodont biostrati graph y and paleoec ology of the Perth Limestone Member. Staunt on Form ation (Pennsy lvanian) of the Illinois Basin. U.S.A. Ill: H. Szaniawski (ed .), Proceedings of the Sixth European Conodont Symposium (ECOS VI). - Palaeont ologia Polonica, 58 . 247-259. Th e Perth Limestone Member of the Staunton Formation in the southeastern part of the Illinois Basin co nsists ofargill aceous limestone s that are in a facies relati on ship with shales and sandstones that commonly are ca lcareous and fossiliferous. Th e Perth conodo nts are do minated by Idiognathodus incurvus. Hindeodus minutus and Neognathodu s bothrops eac h comprises slightly less than 10% of the fauna. Th e other spec ies are minor consti tuents. The Perth is ass igned to the Neog nathodus bothrops- N. bassleri Sub zon e of the N. bothrops Zo ne. but we were unable to co nfirm its assignment to earliest Desmoin esian as oppose d to latest Atokan. Co nodo nt biofacies associations of the Perth refle ct a shallow near- shore marine environment of generally low to moderate energy. but locali zed areas are more variable. particul ar ly in regard to salinity. K e y w o r d s : Co nodo nta. biozonation. paleoecology. Desmoinesian , Penn sylvanian. Illinois Basin. U.S.A. -

Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 1 05

Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 1 05 (1997) Volume 106 p. 105-111 DISTRIBUTION OF LIMESTONE IN THE BRAZIL FORMATION (PENNSYLVANIAN) IN THE SUBSURFACE OF SOUTHWESTERN INDIANA AND WESTERN KENTUCKY John B. Droste and Alan S. Horowitz Department of Geological Sciences Indiana University 1005 East 10th Street Bloomington, Indiana 47405 ABSTRACT. Electric logs and samples of well cuttings indicate the existence of limestone bodies in the lower and middle Brazil Formation of southwest- ern Indiana and western Kentucky. The limestone bodies are elongated north- east-southwest, are as much as 60 feet thick, are as much as 3 miles in length, are interpreted to have formed on slight elevations on the sea floor, and were accumulated contemporaneously with adjacent terrigenous muds and sands until they were finally smothered by these terrigenous sediments. KEYWORDS: Brazil Formation, limestone, Pennsylvanian, subsurface south- western Indiana, subsurface western Kentucky. INTRODUCTION The Brazil Formation in Indiana lies below the Staunton Formation and above the Mansfield Formation in the Raccoon Creek Group (Figure 1). In the type area (Brazil, Clay County, Indiana), the Brazil includes rocks from the base of the Lower Block Coal Member to the top of the Minshall Coal Member (Hutchi- son, 1976). The Upper Block Coal Member is the only other named member of the Brazil Formation. The Brazil coals have irregular distributions along the out- crop and very limited distributions in the subsurface. Because the Minshall coal is of limited extent, the stratigraphic position of the base of the more widespread Perth Limestone Member, or of the sandstone that replaces it, was used in an earlier subsurface study (Droste and Horowitz, 1995) to mark the top of the Brazil. -

Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups

APPENDIX Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups Important fossil taxa are listed down to the lowest practical taxonomic level; in most cases, this will be the ordinal or subordinallevel. Abbreviated stratigraphic units in parentheses (e.g., UCamb-Ree) indicate maximum range known for the group; units followed by question marks are isolated occurrences followed generally by an interval with no known representatives. Taxa with ranges to "Ree" are extant. Data are extracted principally from Harland et al. (1967), Moore et al. (1956 et seq.), Sepkoski (1982), Romer (1966), Colbert (1980), Moy-Thomas and Miles (1971), Taylor (1981), and Brasier (1980). KINGDOM MONERA Class Ciliata (cont.) Order Spirotrichia (Tintinnida) (UOrd-Rec) DIVISION CYANOPHYTA ?Class [mertae sedis Order Chitinozoa (Proterozoic?, LOrd-UDev) Class Cyanophyceae Class Actinopoda Order Chroococcales (Archean-Rec) Subclass Radiolaria Order Nostocales (Archean-Ree) Order Polycystina Order Spongiostromales (Archean-Ree) Suborder Spumellaria (MCamb-Rec) Order Stigonematales (LDev-Rec) Suborder Nasselaria (Dev-Ree) Three minor orders KINGDOM ANIMALIA KINGDOM PROTISTA PHYLUM PORIFERA PHYLUM PROTOZOA Class Hexactinellida Order Amphidiscophora (Miss-Ree) Class Rhizopodea Order Hexactinosida (MTrias-Rec) Order Foraminiferida* Order Lyssacinosida (LCamb-Rec) Suborder Allogromiina (UCamb-Ree) Order Lychniscosida (UTrias-Rec) Suborder Textulariina (LCamb-Ree) Class Demospongia Suborder Fusulinina (Ord-Perm) Order Monaxonida (MCamb-Ree) Suborder Miliolina (Sil-Ree) Order Lithistida -

![Italic Page Numbers Indicate Major References]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6112/italic-page-numbers-indicate-major-references-2466112.webp)

Italic Page Numbers Indicate Major References]

Index [Italic page numbers indicate major references] Abbott Formation, 411 379 Bear River Formation, 163 Abo Formation, 281, 282, 286, 302 seismicity, 22 Bear Springs Formation, 315 Absaroka Mountains, 111 Appalachian Orogen, 5, 9, 13, 28 Bearpaw cyclothem, 80 Absaroka sequence, 37, 44, 50, 186, Appalachian Plateau, 9, 427 Bearpaw Mountains, 111 191,233,251, 275, 377, 378, Appalachian Province, 28 Beartooth Mountains, 201, 203 383, 409 Appalachian Ridge, 427 Beartooth shelf, 92, 94 Absaroka thrust fault, 158, 159 Appalachian Shelf, 32 Beartooth uplift, 92, 110, 114 Acadian orogen, 403, 452 Appalachian Trough, 460 Beaver Creek thrust fault, 157 Adaville Formation, 164 Appalachian Valley, 427 Beaver Island, 366 Adirondack Mountains, 6, 433 Araby Formation, 435 Beaverhead Group, 101, 104 Admire Group, 325 Arapahoe Formation, 189 Bedford Shale, 376 Agate Creek fault, 123, 182 Arapien Shale, 71, 73, 74 Beekmantown Group, 440, 445 Alabama, 36, 427,471 Arbuckle anticline, 327, 329, 331 Belden Shale, 57, 123, 127 Alacran Mountain Formation, 283 Arbuckle Group, 186, 269 Bell Canyon Formation, 287 Alamosa Formation, 169, 170 Arbuckle Mountains, 309, 310, 312, Bell Creek oil field, Montana, 81 Alaska Bench Limestone, 93 328 Bell Ranch Formation, 72, 73 Alberta shelf, 92, 94 Arbuckle Uplift, 11, 37, 318, 324 Bell Shale, 375 Albion-Scioio oil field, Michigan, Archean rocks, 5, 49, 225 Belle Fourche River, 207 373 Archeolithoporella, 283 Belt Island complex, 97, 98 Albuquerque Basin, 111, 165, 167, Ardmore Basin, 11, 37, 307, 308, Belt Supergroup, 28, 53 168, 169 309, 317, 318, 326, 347 Bend Arch, 262, 275, 277, 290, 346, Algonquin Arch, 361 Arikaree Formation, 165, 190 347 Alibates Bed, 326 Arizona, 19, 43, 44, S3, 67. -

Geologic Overview

Chapter C National Coal Resource Assessment Geologic Overview By J.R. Hatch and R.H. Affolter Click here to return to Disc 1 Chapter C of Volume Table of Contents Resource Assessment of the Springfield, Herrin, Danville, and Baker Coals in the Illinois Basin Edited by J.R. Hatch and R.H. Affolter U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1625–D U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Contents Coal Formation ..................................................................................................................................... C1 Plant Material ............................................................................................................................. 1 Phases of Coal Formation ......................................................................................................... 1 Stratigraphic Framework of the Illinois Basin Coals ..................................................................... 1 Raccoon Creek Group ............................................................................................................... 4 Carbondale Formation or Group ............................................................................................... 6 McLeansboro Group................................................................................................................... 6 Structural Setting ............................................................................................................................... 6 Descriptions of the Springfield, Herrin, Danville, and -

Geology and Mineral Deposits of the Jasonville, Quadrangle, Indiana

GEOLOGY AND MINERAL DEPOSITS OF THE JASONVILLE, QUADRANGLE, INDIANA CHARLES E. WIER Indiana Department of Conservation GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Bulletin No. 6 1952 STATE OF INDIANA HENRY F. SCHRICKER GOVERNOR DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION KENNETH M. KUNKEL, DIRECTOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES F. DEISS. STATE GEOLOGIST BLOOMINGTON _____________________________________________________________________ BULLETIN NO. 6 _____________________________________________________________________ GEOLOGY AND MINERAL DEPOSITS OF THE JASONVILLE QUADRANGLE, INDIANA BY CHARLES E. WEIR PRINTED BY AUTHORITY OF THE STATE OF INDIANA BLOOMINGTON, INDIANA February 1952 ______________________________________________________________________ For sale by Geological Survey. Indiana Department of Conservation, Bloomington, Indiana Price $1.00 2 SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL STAFF OF THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES F. DEISS, State Geologist BERNICE M. BANFILL, Administrative Assistant to the State Geologist Coal Section Charles E. Wier, Geologist and Head G. K. Guennel, Paleobotanist Harold C. Hutchison, Geologist (on leave) James T. Stanley, Geologist Geochemistry Section Richard K. Leininger, Spectrographer and Head Robert F. Blakely, Spectrographer Maynard E. Coller, Chemist Geophysics Section Judson Mead, Geophysicist and Research Director Maurice E. Biggs, Geophysicist Charles S. Miller, Instrument Maker Joseph S. Whaley, Junior Geophysicist Glacial Geology Section William D. Thornbury, Geologist and Research Director William J. Wayne, Research Fellow Industrial Minerals Section -

ROCKS ASSOCIATED with the MISSISSIPPIAN-PENNSYLVANIAN UNCONFORMITY in SOUTHWESTERN INDIANA Indiana Department of Conservation

ROCKS ASSOCIATED WITH THE MISSISSIPPIAN-PENNSYLVANIAN UNCONFORMITY IN SOUTHWESTERN INDIANA Indiana Department of Conservation GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Field Conference Guidebook No. 9 1957 STATE OF INDIANA Harold W. Handley, Governor DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION E. Kenneth Marlin, Director GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles F. Deiss, State Geologist Bloomington ______________________________________________________________________________________ Field Conference Guidebook No. 9 ______________________________________________________________________________________ ROCKS ASSOCIATED WITH THE MISSISSIPPIAN-PENNSYLVANIAN UNCONFORMITY IN SOUTHWESTERN INDIANA CONFERENCE SPONSORED BY Geological Survey, Indiana Department of Conservation and Department of Geology, Indiana University, October 4, 5, and 6, 1957 CONFERENCE COMMITTEE Henry H. Gray, Chairman; T. A. Dawson; Duncan J. McGregor; T. G. Perry; and William J. Wayne Printed by authority of the State of Indiana BLOOMINGTON, INDIANA October 1957 ______________________________________________________________________________________ For sale by Geological Survey, Indiana Department of Conservation, Bloomington, Indiana Price $1.00 This page intentionally blank CONTENTS 3 Page Page Introduction ---------------------------------------5 Glossary of rock-type terms ---------------------32 Physiography ----------------------------------5 Literature cited ------------------------------------33 Paleozoic stratigraphy ------------------------5 Postconference road logs ------------------------35 Geomorphic history ---------------------------7 -

Index to the Geologic Names of North America

Index to the Geologic Names of North America GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1056-B Index to the Geologic Names of North America By DRUID WILSON, GRACE C. KEROHER, and BLANCHE E. HANSEN GEOLOGIC NAMES OF NORTH AMERICA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 10S6-B Geologic names arranged by age and by area containing type locality. Includes names in Greenland, the West Indies, the Pacific Island possessions of the United States, and the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1959 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.G. - Price 60 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Major stratigraphic and time divisions in use by the U.S. Geological Survey._ iv Introduction______________________________________ 407 Acknowledgments. _--__ _______ _________________________________ 410 Bibliography________________________________________________ 410 Symbols___________________________________ 413 Geologic time and time-stratigraphic (time-rock) units________________ 415 Time terms of nongeographic origin_______________________-______ 415 Cenozoic_________________________________________________ 415 Pleistocene (glacial)______________________________________ 415 Cenozoic (marine)_______________________________________ 418 Eastern North America_______________________________ 418 Western North America__-__-_____----------__-----____ 419 Cenozoic (continental)___________________________________ -

THE Distributioi-J of DENSOSPORES

THE DISTRIBUTIOi-J OF DENSOSPORES ?lIAVIS A. BUTTERWORTH* Department of Geo1c'gy, University of SIH'ffleld, United Kingdom ABSTRACT by Butter.worth et aZ. (1964a), and by Staplin Densospores include species of the miospore & Jansonms (1064). These workers divide genera Cingulizonafes (Dybova & Jachowicz), the group into [our genera: Densosporites Crisfafisporifes (Potoni6 & Kremp), De1/sosporifes (Berry) Butterworth, J ansonius, Smith & (Berry) and Radiizonafes Staplin & Jansonius Starlin, in which the cingulum is massive from the literature of Europe and ~orth America, and the exine without prominent ornament; and ElIryzol1ot1'ilefrs i'aumoya, Hymellozonofrilefes Naumova and Tremafo:;onotrilefes Kaumova from Cristatisporitfs (Potonie & Kremp) Butter• the Russian literature. An account is given of \\'orth, Jansonius, Smith & Staplin, the taxonomic position of densospores and of their in 'I hich the cingulum and whole of the morphographic variation in clifferent parts of the column. distal surface are covered with rows or Densosporcs have been recorded in large numbers, cristae of verrucae or spines; Cingl{Zizonates mainly from coal seams, from the Devonian to the (Dybova & J achowicz) Butterworth, J an• Permian of the northern hemisphere. The geo• son ius, Smith & StapJin, in which the graphical distribution of these occurrences forms the subject mattcr of the present paper. Tn general cingnlum is prominc:ntly divided into an densospores first occur in abundance in more inner thick and an outer thin part; and northerly regions and are displaced gradually Radiizonates Staplin & Jansonins in \\'hich southwards during the Carboniferous. They are the divi~ion of the cingulum into thicker most common and have the longest ranges, in areas of slow subsidence. -

Storage, Retrieval, and Analysis of Compacted Shale Data

14 Storage, Retrieval, and Analysis of Compacted Shale Data Dirk J. A. van Zyl, L.E. Wood, and C. W. Lovell, Department of Civil Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana W. J. Sisiliano, Indiana State Highway Commission La1ge amounts of soil test data aro beir,g gonoroted by states testing materials fr-om three Joint Highway Research Project (J.HRP) reports for new highway facillties. Of particular Interest to ,omo states Is tho occur completed at Purdue University @, !, ID. A complete rence of shale os a highway motorlal. This paper describes a storage and rotrioval system for compacted lndlnnn shale data (163 setsl. Statistical analyses in summary of all the data available and descriptions of the cluded frequency analysis, bivariate correlation analysis, nnd multiple rogres, geology of Indiana shales and the physiography of Indiana sion analysis. Histograms of the frequency distributions and o summary table are given by van Zyl (§). The table below gives a summary of all the dlfferont statistical descriptors of the parameters are given. Bivariate of the data sets according to geological description. correlation analysis (ono•to-one torrolations) was done for all dota lumped and for data grouped by geologic unit. The multiple regression, concentrated on five-parameter models for predicting Califomla bearing rotio values. It was Geological No. of also found by multlple tllgrenion that the various value, of sloko durabilily in System Geological Stage Data Sets dices can be estimated by using second•ordor equotions. The analyses aro of potontia! value to practicing engineers as a first approximation in design and Pennsylvanian Shelburn formation 3 moy prove useful to engineers rosoarching compacted shale behavior. -

Geology and Structure of the Rough Creek Area, Western Kentucky William D. Johnson Jr. U.S. Geological Survey, Emeritus and Howa

Kentucky Geological Survey James C. Cobb, State Geologist and Director University of Kentucky, Lexington Geology and Structure of the Rough Creek Area, Western Kentucky William D. Johnson Jr. U.S. Geological Survey, Emeritus and Howard R. Schwalb Kentucky Geological Survey and Illinois State Geological Survey, Retired Nomenclature and structure contours do not necessarily conform to current U.S. Geological Survey or Kentucky Geological Survey usage. This work was originally prepared in the late 1990’s and is published here with only editorial improvements. Bulletin 1 Series XII, 2010 Our Mission Our mission is to increase knowledge and understanding of the mineral, energy, and water resources, geologic hazards, and geology of Kentucky for the benefit of the Commonwealth and Nation. © 2006 University of Kentucky Earth Resources—OurFor further information Common contact: Wealth Technology Transfer Officer Kentucky Geological Survey 228 Mining and Mineral Resources Building University of Kentucky Lexington, KY 40506-0107 www.uky.edu/kgs ISSN 0075-5591 Technical Level Technical Level General Intermediate Technical General Intermediate Technical ISSN 0075-5559 Contents Abstract .........................................................................................................................................................1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................7 Geologic Setting.........................................................................................................................................10 -

GUIDE BOOK Fifth Annual Indiana Geologic

GUIDE BOOK Fifth Annual Indiana Geologic Field Conference Pennsylvanian Geology and Mineral Resources of West Central Indiana 1951 GUIDE BOOK Fifth Annual Indiana Geologic Field Conference May 11, 12, and 13, 1951 on PENNSYLVANIAN GEOLOGY AND MINERAL RESOURCES OF WEST CENTRAL INDIANA Conference Leader Ralph E. Esarey Sponsored by Department of Geology, Indiana University, and Geological Survey, Indiana Department of Conservation, Charles F. Deiss, Chairman and State Geologist Compiled by Charles E. Wier and Ralph E. Esarey Indiana University Bloomington, Indiana May 1951 ________________________________________________________________________ For sale by Geological Survey Indiana Department of Conservation, Bloomington, Indiana Price $ .50 CONTENTS Page Introduction............................................................................................................................... 5 Objectives of field conference ........................................................................................ 5 Program............................................................................................................................ 5 Itinerary and stratigraphic sections ............................................................................................ 7 Saturday, May 12 Stop no. 1. Linton no. 28 strip mine, Coal IV.................................................................. 8 Section of Dugger and Linton formations ............................................................. 8 Stop no. 2. Vicksburg strip mine,