Human Uniqueness: a General Theory Author(S): Paul M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Managing the Human Weapon System: a Vision for an Air Force Human-Performance Doctrine

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive DSpace Repository Faculty and Researchers Faculty and Researchers Collection 2009 Managing the Human Weapon System: A Vision for an Air Force Human-Performance Doctrine Tvaryanas, A.P. Tvaryanas, A.P., Brown, L., and Miller, N.L. "Managing the Human Weapon System: A Vision for an Air Force Human-Performance Doctrine", Air & Space Power Journal, pp. 34-41, Summer 2009. http://hdl.handle.net/10945/36508 Downloaded from NPS Archive: Calhoun In air combat, “the merge” occurs when opposing aircraft meet and pass each other. Then they usually “mix it up.” In a similar spirit, Air and Space Power Journal’s “Merge” articles present contending ideas. Readers are free to join the intellectual battlespace. Please send comments to [email protected] or [email protected]. Managing the Human Weapon System A Vision for an Air Force Human-Performance Doctrine LT COL ANTHONY P. TVARYANAS, USAF, MC, SFS COL LEX BROWN, USAF, MC, SFS NITA L. MILLER, PHD* The basic planning, development, organization and training of the Air Force must be well rounded, covering every modern means of waging air war. The Air Force doctrines likewise must be !exible at all times and entirely uninhibited by tradition. —Gen Henry H. “Hap” Arnold N A RECENT paper on America’s Air special operations forces’ declaration that Force, Gen T. Michael Moseley asserted “humans are more important than hardware” that we are at a strategic crossroads as a in asymmetric warfare.2 Consistent with this consequence of global dynamics and view, in January 2004, the deputy secretary of Ishifts in the character of future warfare; he defense directed the Joint Staff to “develop also noted that “today’s con!uence of global the next generation of . -

Sunday Morning Grid 6/22/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/22/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program High School Basketball PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Justin Time Tree Fu LazyTown Auto Racing Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Wildlife Exped. Wild 2014 FIFA World Cup Group H Belgium vs. Russia. (N) SportCtr 2014 FIFA World Cup: Group H 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Program Crazy Enough (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Paid Program RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Wild Places Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Kitchen Lidia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Healthy Hormones Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Into the Blue ›› (2005) Paul Walker. (PG-13) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Backyard 2014 Copa Mundial de FIFA Grupo H Bélgica contra Rusia. (N) República 2014 Copa Mundial de FIFA: Grupo H 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Harvest In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Austria. -

Swordplay Through the Ages Daniel David Harty Worcester Polytechnic Institute

Worcester Polytechnic Institute Digital WPI Interactive Qualifying Projects (All Years) Interactive Qualifying Projects April 2008 Swordplay Through The Ages Daniel David Harty Worcester Polytechnic Institute Drew Sansevero Worcester Polytechnic Institute Jordan H. Bentley Worcester Polytechnic Institute Timothy J. Mulhern Worcester Polytechnic Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/iqp-all Repository Citation Harty, D. D., Sansevero, D., Bentley, J. H., & Mulhern, T. J. (2008). Swordplay Through The Ages. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/iqp-all/3117 This Unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Interactive Qualifying Projects at Digital WPI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Interactive Qualifying Projects (All Years) by an authorized administrator of Digital WPI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IQP 48-JLS-0059 SWORDPLAY THROUGH THE AGES Interactive Qualifying Project Proposal Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation by __ __________ ______ _ _________ Jordan Bentley Daniel Harty _____ ________ ____ ________ Timothy Mulhern Drew Sansevero Date: 5/2/2008 _______________________________ Professor Jeffrey L. Forgeng. Major Advisor Keywords: 1. Swordplay 2. Historical Documentary Video 3. Higgins Armory 1 Contents _______________________________ ........................................................................................0 Abstract: .....................................................................................................................................2 -

Adrian Maher

ADRIAN MAHER WRITER/DIRECTOR/SUPERVISING PRODUCER Los Angeles, CA Cell: (310) 922-3080 Email: [email protected] Website: www.maherproductions.com ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE – REALITY AND DOCUMENTARY TELEVISION More than two decades of experience as a writer/director of documentary television programs, print journalist, on-air reporter, book author and private investigator. Strong writing, directing, producing, voiceover, investigative, digital media, and managerial skills. UNSUNG HOLLYWOOD: HARLEM GLOBETROTTERS: (TV ONE NETWORK) (ASmith and Company) Wrote, Directed and Produced a one -hour episode on the history of the Harlem Globetrotters from their founding in Chicago in 1927 to their present-day status as one of the most recognizable sports brands in the world. SPLIT-SECOND DECISION: (MSNBC) (The Gurin Company) Wrote, Directed and Produced three one-hour documentaries about people caught in catastrophic situations and the instant decisions they make to survive. UNSUNG HOLLYWOOD: RICHARD ROUNDTREE: (TV ONE NETWORK) (ASmith and Company) Wrote, and Produced a one-hour episode/biography on America’s first black-action movie star – Richard Roundtree – (star of “Shaft”) and the “blaxploitation” era in Hollywood films. TRIGGERS: WEAPONS THAT CHANGED THE WORLD (MILITARY CHANNEL) (Morningstar Entertainment) Wrote and Produced several episodes on history’s most fearsome weapons including “Gatling Guns,” “Tanks” and “Light Machine Guns.” -

SFU Thesis Template Files

“To Fight the Battles We Never Could”: The Militarization of Marvel’s Cinematic Superheroes by Brett Pardy B.A., The University of the Fraser Valley, 2013 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication Faculty of Communication, Art, and Technology Brett Pardy 2016 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2016 Approval Name: Brett Pardy Degree: Master of Arts Title: “To Fight the Battles We Never Could”: The Militarization of Marvel’s Cinematic Superheroes Examining Committee: Chair: Frederik Lesage Assistant Professor Zoë Druick Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Adel Iskander Supervisor Assistant Professor Michael Ma External Examiner Faculty Member Department of Criminology Kwantlen Polytechnic University Date Defended/Approved: June 16, 2016 ii Abstract The Marvel comics film adaptations have been some of the most successful Hollywood products of the post 9/11 period, bringing formerly obscure cultural texts into the mainstream. Through an analysis of the adaptation process of Marvel Entertainment’s superhero franchise from comics to film, I argue that a hegemonic American model of militarization has been used by Hollywood as a discursive formation with which to transform niche properties into mass market products. I consider the locations of narrative ambiguities in two key comics texts, The Ultimates (2002-2007) and The New Avengers (2005-2012), as well as in the film The Avengers (2012), and demonstrate the significant reorientation of the film franchise towards the American military’s “War on Terror”. While Marvel had attempted to produce film adaptations for decades, only under the new “militainment” discursive formation was it finally successful. -

State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations for Fiscal Year 2018

STATE, FOREIGN OPERATIONS, AND RELATED PROGRAMS APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2018 TUESDAY, MAY 9, 2017 U.S. SENATE, SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS, Washington, DC. The subcommittee met at 2:30 p.m., in room SD–192, Dirksen Senate Office Building, Hon. Lindsey Graham (chairman) pre- siding. Present: Senators Graham, Moran, Boozman, Daines, Leahy, Durbin, Shaheen, Coons, Murphy and Van Hollen. UNITED STATES DEMOCRACY ASSISTANCE STATEMENTS OF: HON. MADELEINE ALBRIGHT, CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD, THE NA- TIONAL DEMOCRATIC INSTITUTE HON. STEPHEN HADLEY, CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD, THE UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE HON. VIN WEBER, CO-VICE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD, THE NA- TIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR DEMOCRACY HON. JAMES KOLBE, VICE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD, THE INTER- NATIONAL REPUBLICAN INSTITUTE TESTIMONY FROM DEMOCRACY PROGRAM BENEFICIARIES OUTSIDE WITNESS TESTIMONY SUBMITTED SUBSEQUENT TO THE HEARING OPENING STATEMENT OF SENATOR LINDSEY GRAHAM Senator GRAHAM. Thank you all. The subcommittee will come to order. Today, our hearing is on United States Democracy Assist- ance. I would like to welcome our witnesses who deserve long, glowing introductions—but you’re not going to get one because we got to get on one with the hearing. We’ve got Madeleine Albright, Chairman of the Board of the Na- tional Democratic Institute and former Secretary of State. Wel- come, Ms. Albright. James Kolbe, Vice-Chairman of the Board of the International Republican Institute. Jim, welcome. Vin Weber, Co-Vice Chairman of the Board of the National En- dowment for Democracy, all around good guy, Republican type. Stephen Hadley, Chairman of the Board of the United States In- stitute of Peace. -

Hypersonic Hyperstitions

HYPERSONIC HYPERSTITIONS Šum #11 HYPERSONIC HYPERSTITIONS Šum #11 HYPERSONIC HYPERSTITIONS Šum #11 Šum #11 HYPERSONIC HYPERSTITIONS There used to be supersonics and superstitions. Then hyper came along. Marko Peljhan invited Šum journal to produce a special issue that would accompany his exhibition Here we go again… SYSTEM 317 in the Slovenian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. The invitation included, among a lot of referential vectors, this short description: “The exhibition will feature a full-scale model of a hypersonic aircraft system and will appropriate, combine and hack actual US, Russian and Chinese blueprints. The cockpit will be done in the style of a West Coast lowrider … how to light a match and keep it lit during a hurricane.” Šum in turn approached theory-fiction and hard sci-fi, that is, mobilised their agents, to provide overlaps with Peljhan’s exhibition and his work in general. War. Evolution. Tech. Escape/Exit. The Arctic. Conversion/Convergence. Transpiercement. Surrationality. Shadow-subsuming. Intelligent Battlespace. UGO. Godspeed. 10.851735 1447 1448 10.851735 1451 SURRATIONAL FUGITIVES LUCIANA PARISI 1467 ETERNAL PHENOTYPE MIROSLAV GRIŠKO 1499 AN EXEGETICAL INCURSION OF THE EMERGENT “INTELLIGENT BATTLESPACE” MANABRATA GUHA 1531 CAPITAL, WAR AND LOVE PRIMOŽ KRAŠOVEC 1563 THE WISDOM OF CROWDS PETER WATTS 1595 DIRECTORATE OF CELESTIAL SURVEILLANCE, 1665 ANDREJ TOMAŽIN 1627 UNIDENTIFIED GLIDING OBJECT: THE DAY THE EARTH WAS UNMOORED REZA NEGARESTANI Appendix: 1659 YAMAL EVENTS REPORT 2071 EDMUND BERGER, KEVIN ROGAN 10.851735 1449 1450 10.851735 Surrational Fugitives LUCIANA PARISI 10.851735 1451 SURRATIONAL FUGITIVES 1452 10.851735 In an attempt to contain the human exodus from planet earth, today at 09:09 am, the Planetary Security Council has ordered a shutdown of celestial borders: gateways of hypersonic vessels that pierce the terrestrial atmosphere and fly 9 million light years away from planetary existence. -

Contextualising Legal Reviews for Autonomous Weapon Systems

Missing Man: Contextualising Legal Reviews for Autonomous Weapon Systems DISSERTATION of the University of St. Gallen, School of Management, Economics, Law, Social Sciences and International Affairs to obtain the title of Doctor of Philosophy in Law submitted by Fredrik von Bothmer from Germany Approved on the application of Prof. Dr. Thomas Burri and Prof. Dirk Lehmkuhl, PhD Dissertation no. 4804 Difo-Druck GmbH, Bamberg 2018 The University of St. Gallen, School of Management, Economics, Law, Social Sciences and International Affairs hereby consents to the printing of the present dissertation, without hereby expressing any opinion on the views herein expressed. St. Gallen, May 22, 2018 The President: Prof. Dr. Thomas Bieger II Table of Contents I. Introduction: Key Categories and Terminology ............................................. 7 A. Just another New Emerging Weapon Technology? ................................... 12 B. Terminology and Definition ....................................................................... 18 II. Legal Challenges posed by AWS: IHL and Responsibility .......................... 27 A. AWS as Means and Methods of Warfare ................................................... 33 B. Illegality of AWS per se .............................................................................. 34 1. Basic rules for inherent illegality of weapon systems ............................ 34 a) Indiscriminate weapon by nature ........................................................ 34 b) Unnecessary suffering or superfluous injury -

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings TITLE PUBLICATION INFORMATION NUMBER DATE LANG 1-800-INDIA Mitra Films and Thirteen/WNET New York producer, Anna Cater director, Safina Uberoi. VD-1181 c2006. eng 1 giant leap Palm Pictures. VD-825 2001 und 1 on 1 V-5489 c2002. eng 3 films by Louis Malle Nouvelles Editions de Films written and directed by Louis Malle. VD-1340 2006 fre produced by Argosy Pictures Corporation, a Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer picture [presented by] 3 godfathers John Ford and Merian C. Cooper produced by John Ford and Merian C. Cooper screenplay VD-1348 [2006] eng by Laurence Stallings and Frank S. Nugent directed by John Ford. Lions Gate Films, Inc. producer, Robert Altman writer, Robert Altman director, Robert 3 women VD-1333 [2004] eng Altman. Filmocom Productions with participation of the Russian Federation Ministry of Culture and financial support of the Hubert Balls Fund of the International Filmfestival Rotterdam 4 VD-1704 2006 rus produced by Yelena Yatsura concept and story by Vladimir Sorokin, Ilya Khrzhanovsky screenplay by Vladimir Sorokin directed by Ilya Khrzhanovsky. a film by Kartemquin Educational Films CPB producer/director, Maria Finitzo co- 5 girls V-5767 2001 eng producer/editor, David E. Simpson. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. ita Flaiano, Brunello Rondi. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. -

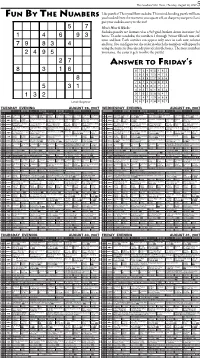

Answer to Friday's

The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, August 28, 2007 5 Like puzzles? Then you’ll love sudoku. This mind-bending puzzle will have FUN BY THE NUMBERS you hooked from the moment you square off, so sharpen your pencil and put your sudoku savvy to the test! Here’s How It Works: Sudoku puzzles are formatted as a 9x9 grid, broken down into nine 3x3 boxes. To solve a sudoku, the numbers 1 through 9 must fill each row, col- umn and box. Each number can appear only once in each row, column and box. You can figure out the order in which the numbers will appear by using the numeric clues already provided in the boxes. The more numbers you name, the easier it gets to solve the puzzle! ANSWER TO FRIDAY’S TUESDAY EVENING AUGUST 28, 2007 WEDNESDAY EVENING AUGUST 29, 2007 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Mindfreak Criss Angel Criss Angel Criss Angel Dog Bounty Dog Bounty CSI: Miami: Double Jeop- CSI: Miami: Driven The Sopranos: Whitecaps A new Dog Bounty CSI: Miami: Double Jeop- 36 47 A&E (R) (R) (R) (TVPG) (TVPG) (R) (R) (R) (R) (R) 36 47 A&E ardy (TV14) (HD) (TV14) (HD) house. (TVMA) (HD) (R) ardy (TV14) (HD) Laughs Laughs i-Caught Amateur video. -

ISSN 1553-9768 Summer 2008 Volume 8, Edition 3

ISSN 1553-9768 Summer 2008 Volume 8, Edition 3 V JJoouurrnnaall ooff SSppeecciiaall OOppeerraattiioonnss MMeeddiicciinnee o l u m A Peer Reviewed Journal for SOF Medical Professionals e 8 , E d i t i o n 3 / S u m m e r 0 8 J o u r n a l o f S p e c i a l O p e r a t i o n s M e d i c i n e N THIS DITION PDATED ACTICAL OMBAT ASUALTY ARE UIDELINES I E : U T C C C G THIS EDITION’S FEATURE ARTICLES: I ● Thoughts on Aid Bags: Part One S S ● Canine Tactical Field Care: Part One – Physical Examination and Medical Assessment N ● Intermittent Hypoxic Exposure Protocols to Rapidly Induce Altitude Acclimatization in the SOF Operator 1 5 ● A Series of Special Operations Forces Patients with Sexual Dysfunction in Association with a Mental Health 5 3 Condition - 9 ● CME - Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: Situational Awareness for Special Operations Medical Providers 7 6 ● Spontaneous Pneumopericardium, Pneumomediastinum and Subcutaneous Emphysema in a 22-year old 8 Active Duty Soldier Dediicated to the Indomiitablle Spiiriit & Sacriifiices of the SOF Mediic Journal of Special Operations Medicine EXECUTIVE EDITOR MANAGING EDITOR Farr, Warner D., MD, MPH, MSS Landers, Michelle DuGuay, MBA, BSN [email protected] [email protected] Medical Editor Gilpatrick, Scott, APA-C [email protected] Assistant Editor Contributing Editor Parsons, Deborah A., BSN Schissel, Daniel J., MD (Med Quiz “Picture This”) CME MANAGERS Kharod, Chetan U. MD, MPH -- USUHS CME Sponsor Officers Enlisted Landers, Michelle DuGuay, MBA, BSN Gilpatrick, Scott, PA-C [email protected] [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Ackermann, Bret T., DO Hoyt, Robert E. -

New Technologies and Warfare

New technologies and warfare Volume 94 Number 886 Summer 2012 94 Number 886 Summer 2012 Volume Volume 94 Number 886 Summer 2012 Editorial: Science cannot be placed above its consequences Interview with Peter W. Singer New capabilities in warfare: an overview [...] Alan Backstrom and Ian Henderson Cyber conflict and international humanitarian law Herbert Lin Get off my cloud: cyber warfare, international humanitarian law, and the protection of civilians Cordula Droege Some legal challenges posed by remote attack William Boothby Pandora’s box? Drone strikes under jus ad bellum, jus in bello, and international human rights law Stuart Casey-Maslen Categorization and legality of autonomous and remote weapons systems and warfare technologies New Humanitarian debate: Law, policy, action Hin-Yan Liu Nanotechnology and challenges to international humanitarian law: a preliminary legal assessment Hitoshi Nasu Conflict without casualties … a note of caution: non-lethal weapons and international humanitarian law Eve Massingham On banning autonomous weapon systems: human rights, automation, and the dehumanization of lethal decision-making Peter Asaro Beyond the Call of Duty: why shouldn’t video game players face the same dilemmas as real soldiers? Ben Clarke, Christian Rouffaer and François Sénéchaud Documenting violations of international humanitarian law from [...] Joshua Lyons The roles of civil society in the development of standards around new weapons and other technologies of warfare Brian Rappert, Richard Moyes, Anna Crowe and Thomas Nash The