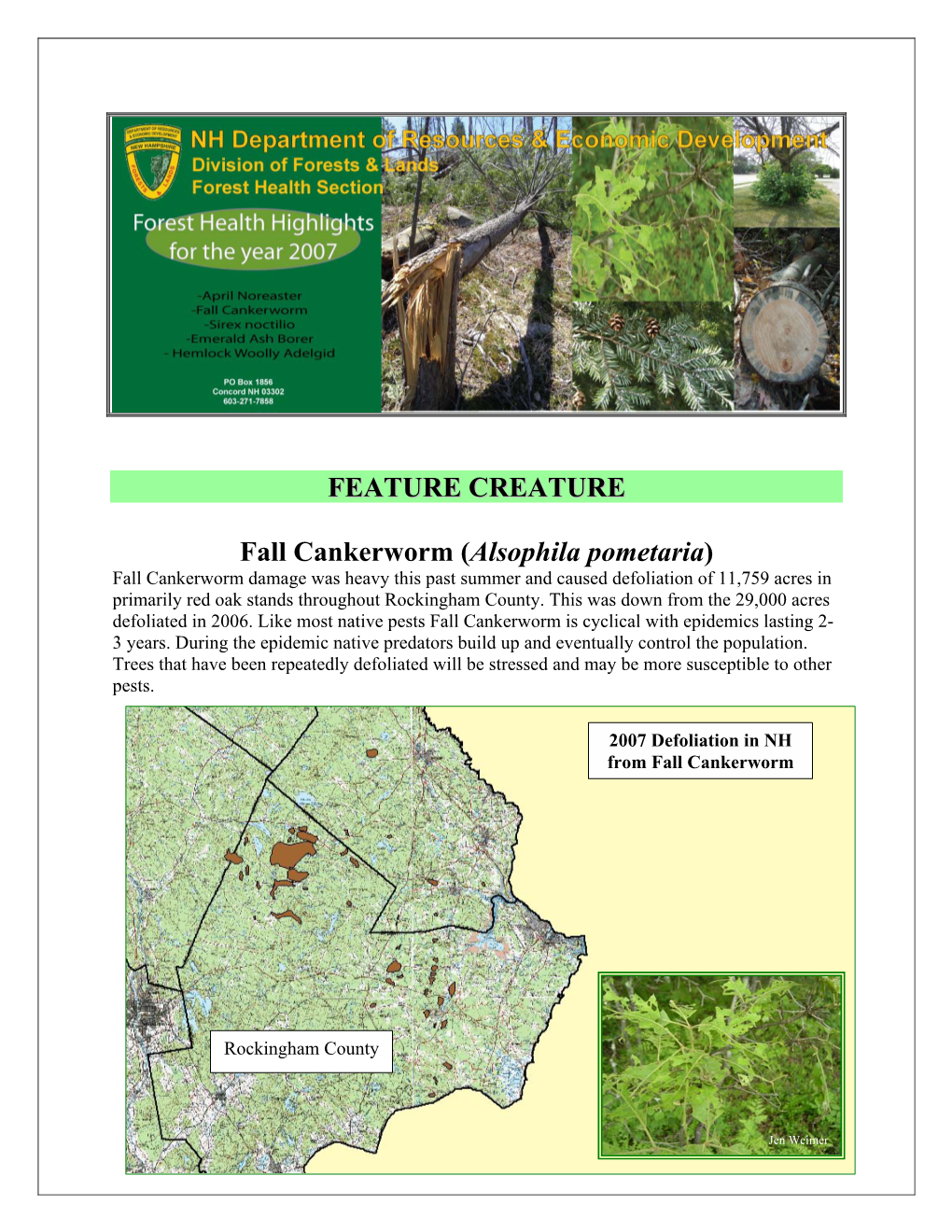

FEATURE CREATURE Fall Cankerworm (Alsophila Pometaria)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall Cankerworm

Pest Profile Photo credit: David Keith & Tim Miller, UNL Entomology Extension Common Name: Fall Cankerworm Scientific Name: Alsophila pometaria Order and Family: Lepidoptera, Geometridae Size and Appearance: Length (mm) Appearance Egg dark grayish-brown with a dot and a ring 1.0 mm on top Larva/Nymph vary between light green and dark 25.0 mm (mature larvae) brownish-green have white lines running down their body from the head to the tip of the abdomen dark-brownish green caterpillars have a black stripe the length of their back Adult males are small, have wings, and are grayish color with some white lines along 25.0 – 35.0 mm (male the wings wingspread) females have a grayish colored body and 10.0 – 12.0 mm (female) wingless Pupa (if applicable) yellow to yellow-green in color wrapped in a silken cocoon Type of feeder (Chewing, sucking, etc.): Chewing (caterpillar) Host plant/s: black cherry, basswood, red and white oaks, beech, ash, boxelder, elm, sugar and red maples Description of Damage (larvae and adults): When the larvae are young, they eat on the underside of the leaves, making the leaf appear skeletonized. As the larvae get older, they cause more damage by eating almost the whole leaf. In some cases, the damage is to the extent of defoliation of the tree, especially in severe cases of outbreaks. Sometimes in bad outbreaks, these caterpillars can defoliate many trees. References: Ciesla, M, W. & Asaro, C (2016) Fall Crankerworm. Forest Insect & Disease Leaflet 182. Published by U.S. Deparment of Agriculture- Forest Service. Portland, Oregon. -

Softwood Insect Pests

Forest & Shade Tree Insect & Disease Conditions for Maine A Summary of the 2011 Situation Forest Health & Monitoring Division Maine Forest Service Summary Report No. 23 MAINE DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION March 2012 Augusta, Maine Forest Insect & Disease—Advice and Technical Assistance Maine Department of Conservation, Maine Forest Service Insect and Disease Laboratory 168 State House Station, 50 Hospital Street, Augusta, Maine 04333-0168 phone (207) 287-2431 fax (207) 287-2432 http://www.maine.gov/doc/mfs/idmhome.htm The Maine Forest Service/Forest Health and Monitoring (FH&M) Division maintains a diagnostic laboratory staffed with forest entomologists and a forest pathologist. The staff can provide practical information on a wide variety of forest and shade tree problems for Maine residents. Our technical reference library and insect collection enables the staff to accurately identify most causal agents. Our website is a portal to not only our material and notices of current forest pest issues but also provides links to other resources. A stock of information sheets and brochures is available on many of the more common insect and disease problems. We can also provide you with a variety of useful publications on topics related to forest insects and diseases. Submitting Samples - Samples brought or sent in for diagnosis should be accompanied by as much information as possible including: host plant, type of damage (i.e., canker, defoliation, wilting, wood borer, etc.), date, location, and site description along with your name, mailing address and day-time telephone number or e-mail address. Forms are available (on our Web site and on the following page) for this purpose. -

The Winter Moth ( Operophtera Brumata) and Its Natural Enemies in Orkney

Spatial ecology of an insect host-parasitoid-virus interaction: the winter moth ( Operophtera brumata) and its natural enemies in Orkney Simon Harold Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Faculty of Biological Sciences September 2009 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement ©2009 The University of Leeds and Simon Harold ii Acknowledgements I gratefully acknowledge the support of my supervisors Steve Sait and Rosie Hails for their continued advice and support throughout the duration of the project. I particularly thank Steve for his patience, enthusiasm, and good humour over the four years—and especially for getting work back to me so quickly, more often than not because I had sent it at the eleventh hour. I would also like to express my gratitude to the Earth and Biosphere Institute (EBI) at the University of Leeds for funding this project in the first instance. Steve Carver also helped secure funding. The molecular work was additionally funded by both a NERC short-term grant, and funding from UKPOPNET, to whom I am also grateful. None of the fieldwork, and indeed the scope and scale of the project, would have been possible if not for the stellar cast of fieldworkers that made the journey to Orkney. They were (in order of appearance): Steve Sait, Rosie Hails, Jackie Osbourne, Bill Tyne, Cathy Fiedler, Ed Jones, Mike Boots, Sandra Brand, Shaun Dowman, Rachael Simister, Alan Reynolds, Kim Hutchings, James Rosindell, Rob Brown, Catherine Bourne, Audrey Zannesse, Leo Graves and Steven White. -

Maine Forest Service MAINE DEPARTMENT OF

Maine Forest Service ● MAINE DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION FALL CANKERWORM Alsophila pometaria (Harris) Insect and Disease Laboratory ● 168 State House Station ● 50 Hospital Street ● Augusta, Maine ● 043330168 Damage This important pest of forest and shade trees occurs generally throughout most of Northeastern America where it feeds on a variety of hardwoods. Damage is first noticed in early May when feeding by the tiny larvae known as "cankerworms," "loopers," "inchworms" or "measuring worms" on the opening buds and expanding leaves causes the foliage to be skeletonized. Later as the larvae mature all but the midrib (and veins) of leaves are devoured. Occasional outbreaks of this pest in Maine have caused severe defoliation of oak and elm. The outbreaks are most often localized and usually last three to four years before natural control factors cause the population to collapse. Trees subjected to two or more years of heavy defoliation may be seriously damaged, especially weaker trees or trees growing on poor sites. Hosts Its preferred hosts are oak, elm and apple, but it also occurs on maple, beech, ash, poplar, box elder, basswood, and cherry. Description and Habits The wingless, greyishbrown female cankerworm moths emerge from the duff with the onset of cold weather in October and November and crawl up the tree trunks. The male moth is greyishbrown with a one inch wing span. Males can often be seen flitting through infested stands during the day or warmer nights during hunting season. The females are not often seen. Females deposit their eggs in singlelayered compact masses of 100 or more on the bark of smaller branches and twigs of trees often high in the crown from October to early December. -

Forest Health Conditions in Ontario, 2017

Forest Health Conditions in Ontario, 2017 Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Forest Health Conditions in Ontario, 2017 Compiled by: • Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Science and Research Branch © 2018, Queen’s Printer for Ontario Printed in Ontario, Canada Find the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry on-line at: <http://www.ontario.ca>. For more information about forest health monitoring in Ontario visit the natural resources website: <http://ontario.ca/page/forest-health-conditions> Some of the information in this document may not be compatible with assistive technologies. If you need any of the information in an alternate format, please contact [email protected]. Cette publication hautement spécialisée Forest Health Conditions in Ontario, 2017 n'est disponible qu'en anglais en vertu du Règlement 671/92 qui en exempte l’application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l’aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec le ministère des Richesses naturelles au <[email protected]>. ISSN 1913-617X (Online) ISBN 978-1-4868-2275-1 (2018, pdf) Contents Contributors ........................................................................................................................ 4 État de santé des forêts 2017 ............................................................................................. 5 Introduction......................................................................................................................... 6 Contributors Weather patterns ................................................................................................... -

A Comprehensive DNA Barcode Library for the Looper Moths (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) of British Columbia, Canada

AComprehensiveDNABarcodeLibraryfortheLooper Moths (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) of British Columbia, Canada Jeremy R. deWaard1,2*, Paul D. N. Hebert3, Leland M. Humble1,4 1 Department of Forest Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, 2 Entomology, Royal British Columbia Museum, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, 3 Biodiversity Institute of Ontario, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada, 4 Canadian Forest Service, Natural Resources Canada, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada Abstract Background: The construction of comprehensive reference libraries is essential to foster the development of DNA barcoding as a tool for monitoring biodiversity and detecting invasive species. The looper moths of British Columbia (BC), Canada present a challenging case for species discrimination via DNA barcoding due to their considerable diversity and limited taxonomic maturity. Methodology/Principal Findings: By analyzing specimens held in national and regional natural history collections, we assemble barcode records from representatives of 400 species from BC and surrounding provinces, territories and states. Sequence variation in the barcode region unambiguously discriminates over 93% of these 400 geometrid species. However, a final estimate of resolution success awaits detailed taxonomic analysis of 48 species where patterns of barcode variation suggest cases of cryptic species, unrecognized synonymy as well as young species. Conclusions/Significance: A catalog of these taxa meriting further taxonomic investigation is presented as well as the supplemental information needed to facilitate these investigations. Citation: deWaard JR, Hebert PDN, Humble LM (2011) A Comprehensive DNA Barcode Library for the Looper Moths (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) of British Columbia, Canada. PLoS ONE 6(3): e18290. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018290 Editor: Sergios-Orestis Kolokotronis, American Museum of Natural History, United States of America Received August 31, 2010; Accepted March 2, 2011; Published March 28, 2011 Copyright: ß 2011 deWaard et al. -

Influence of Habitat and Bat Activity on Moth Community Composition and Seasonal Phenology Across Habitat Types

INFLUENCE OF HABITAT AND BAT ACTIVITY ON MOTH COMMUNITY COMPOSITION AND SEASONAL PHENOLOGY ACROSS HABITAT TYPES BY MATTHEW SAFFORD THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Entomology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2018 Urbana, Illinois Advisor: Assistant Professor Alexandra Harmon-Threatt, Chair and Director of Research ABSTRACT Understanding the factors that influence moth diversity and abundance is important for monitoring moth biodiversity and developing conservation strategies. Studies of moth habitat use have primarily focused on access to host plants used by specific moth species. How vegetation structure influences moth communities within and between habitats and mediates the activity of insectivorous bats is understudied. Previous research into the impact of bat activity on moths has primarily focused on interactions in a single habitat type or a single moth species of interest, leaving a large knowledge gap on how habitat structure and bat activity influence the composition of moth communities across habitat types. I conducted monthly surveys at sites in two habitat types, restoration prairie and forest. Moths were collected using black light bucket traps and identified to species. Bat echolocation calls were recorded using ultrasonic detectors and classified into phonic groups to understand how moth community responds to the presence of these predators. Plant diversity and habitat structure variables, including tree diameter at breast height, ground cover, and vegetation height were measured during summer surveys to document how differences in habitat structure between and within habitats influences moth diversity. I found that moth communities vary significantly between habitat types. -

Landscape Message: May 24, 2019 | Umass Center for Agriculture, Food and the Environment

5/24/2019 Landscape Message: May 24, 2019 | UMass Center for Agriculture, Food and the Environment Apply Give Search (/) LNUF Home (/landscape) About (/landscape/about) Newsletters & Updates (/landscape/newsletters-updates) Publications & Resources (/landscape/publications-resources) Services (/landscape/services) Education & Events (/landscape/upcoming-events) Make a Gift (https://securelb.imodules.com/s/1640/alumni/index.aspx? sid=1640&gid=2&pgid=443&cid=1121&dids=2540) (/landscape) Search the Center for Agriculture, Food and the Environment Search this site Search Landscape Message: May 24, 2019 May 24, 2019 Issue: 9 UMass Extension's Landscape Message is an educational newsletter intended to inform and guide Massachusetts Green Industry professionals in the management of our collective landscape. Detailed reports from scouts and Extension specialists on growing conditions, pest activity, and cultural practices for the management of woody ornamentals, trees, and turf are regular features. The following issue has been updated to provide timely management information and the latest regional news and environmental data. The Landscape Message will be updated weekly in May and June. The next message will be posted on May 31. To receive immediate notication when the next Landscape Message update is posted, be sure to join our e-mail list (/landscape/email-list). To read individual sections of the message, click on the section headings below to expand the content: Scouting Information by Region ag.umass.edu/landscape/landscape-message-may-24-2019 1/18 5/24/2019 Landscape Message: May 24, 2019 | UMass Center for Agriculture, Food and the Environment Environmental Data The following data was collected on or about May 22, 2019. -

Local Outbreaks of Operophtera Brumata and Operophtera Fagata Cannot Be Explained by Low Vulnerability to Pupal Predation

Postprint version. Original publication in: Agricultural and Forest Entomology (2010) 12(1): 81-87 doi: 10.1111/j.1461-9563.2009.00455.x Local outbreaks of Operophtera brumata and Operophtera fagata cannot be explained by low vulnerability to pupal predation Annette Heisswolf, Miia Käär, Tero Klemola, Kai Ruohomäki Section of Ecology, Department of Biology, University of Turku, FI-20014 Turku, Finland Abstract. One of the unresolved questions in studies on population dynamics of for- est Lepidoptera is why some populations at times reach outbreak densities, whereas oth- ers never do. Resolving this question is especially challenging if populations of the same species in different areas or of closely-related species in the same area are considered. The present study focused on three closely-related geometrid moth species, autumnal Epirrita autumnata, winter Operophtera brumata and northern winter moths Operophtera fagata, in southern Finland. There, winter and northern winter moth populations can reach outbreak densities, whereas autumnal moth densities stay relatively low. We tested the hypothesis that a lower vulnerability to pupal predation may explain the observed differences in population dynamics. The results obtained do not support this hypothesis because pupal predation probabilities were not significantly different between the two genera within or without the Operophtera outbreak area or in years with or without a current Operophtera outbreak. Overall, pupal predation was even higher in winter and northern winter moths than in autumnal moths. Differences in larval predation and parasitism, as well as in the repro- ductive capacities of the species, might be other candidates. Keywords. Epirrita autumnata; forest Lepidoptera; Operophtera brumata; Operoph- tera fagata; outbreak; population dynamics; pupal predation. -

Exposure of Noctuid and Geometrid Development Stages in Oak Forests

Glavendekić & Mihajlović: Exposure of noctuid and geometrid development stages in oak forests EXPOSURE OF NOCTUID AND GEOMETRID DEVELOPMENT STAGES IN OAK FORESTS Milka M. Glavendekić, Ljubodrag S. Mihajlović Faculty of Forestry University of Belgrade, Kneza Višeslava 1, 11030 Belgrade, Serbia (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract The research was carried out in the period 1985-2005 in oak forests in Serbia. During the research of winter moths in oak forests of Serbia we recorded 9 outbreaking winter moth species: Colotois pennaria L., Agriopis aurantiaria Hbn., Erannis defoliaria Cl., Alsophila aescularia D.& Sch., A. aceraria D.& Sch., Operophtera brumata L., Apocheima pilosaria D.& Sch., Agriopis leucophaearia D.& Sch., A. marginaria F. The most significant noctuids are Orthosia spp. There are 38 parasitoids of the winter moths recorded and they fall into the families Braconidae, Ichneumonidae, Eulophidae, Torymidae, Trichogrammatidae, Scelionidae and Tachinidae. Egg parasitoids were recorded at 3 localities: Brankovac, Mala Moštanica and wide area of National Park Djerdap. Hyperparasitoids of winter moths in Serbia have also been studied. We recorded altogether 12 species of winter moth hyperparasitoids. The method of exposure was applied in egg and larva stages. While total parasitism in the natural population varies between 12.50-28.57 %, in the exposed conditions there were between 27.31-43.75 % parasitized caterpillars were recorded. The method of host exposure could be suitable for the local increase of abundance of parasitoids of winter moth eggs, larvae and pupae. Keywords: Defoliators, oak, Geometridae, Noctuidae 1. Introduction In Serbia forests cover about 2,313,000 ha, or 26.2 % of the whole territory. -

The River Network of the Piedras Blancas Park.Pdf

Natural and Cultural History of the Golfo Dulce Region, Costa Rica Historia natural y cultural de la región del Golfo Dulce, Costa Rica Anton WEISSENHOFER , Werner HUBER , Veronika MAYER , Susanne PAMPERL , Anton WEBER , Gerhard AUBRECHT (scientific editors) Impressum Katalog / Publication: Stapfia 88 , Zugleich Kataloge der Oberösterreichischen Landesmuseen N.S. 80 ISSN: 0252-192X ISBN: 978-3-85474-195-4 Erscheinungsdatum / Date of deliVerY: 9. Oktober 2008 Medieninhaber und Herausgeber / CopYright: Land Oberösterreich, Oberösterreichische Landesmuseen, Museumstr.14, A-4020 LinZ Direktion: Mag. Dr. Peter Assmann Leitung BiologieZentrum: Dr. Gerhard Aubrecht Url: http://WWW.biologieZentrum.at E-Mail: [email protected] In Kooperation mit dem Verein Zur Förderung der Tropenstation La Gamba (WWW.lagamba.at). Wissenschaftliche Redaktion / Scientific editors: Anton Weissenhofer, Werner Huber, Veronika MaYer, Susanne Pamperl, Anton Weber, Gerhard Aubrecht Redaktionsassistent / Assistant editor: FritZ Gusenleitner LaYout, Druckorganisation / LaYout, printing organisation: EVa Rührnößl Druck / Printing: Plöchl-Druck, Werndlstraße 2, 4240 Freistadt, Austria Bestellung / Ordering: http://WWW.biologieZentrum.at/biophp/de/stapfia.php oder / or [email protected] Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschütZt. Jede VerWertung außerhalb der en - gen GrenZen des UrheberrechtsgesetZes ist ohne Zustimmung des Medieninhabers unZulässig und strafbar. Das gilt insbesondere für VerVielfältigungen, ÜbersetZungen, MikroVerfilmungen soWie die Einspeicherung und Verarbeitung in elektronischen SYstemen. Für den Inhalt der Abhandlungen sind die Verfasser Verant - Wortlich. Schriftentausch erWünscht! All rights reserVed. No part of this publication maY be reproduced or transmitted in anY form or bY anY me - ans Without prior permission from the publisher. We are interested in an eXchange of publications. Umschlagfoto / CoVer: Blattschneiderameisen. Photo: AleXander Schneider. -

What Moths Fly in Winter? the Assemblage of Moths Active in a Temperate Deciduous Forest During the Cold Season in Central Poland

J. Entomol. Res. Soc., 17(2): 59-71, 2015 ISSN:1302-0250 What Moths Fly in Winter? The Assemblage of Moths Active in a Temperate Deciduous Forest During the Cold Season in Central Poland Jacek HIKISZ1 Agnieszka SOSZYŃSKA-MAJ2* Department of Invertebrate Zoology and Hydrobiology, University of Lodz, Banacha 12/16, 90-237 Łódź, POLAND, e-mails: 1 [email protected], 2*[email protected] ABSTRACT The composition and seasonal dynamics of the moth assemblage active in a temperate deciduous forest of Central Poland in autumn and spring was studied in two seasons 2007/2008 and 2008/2009. The standard light trapping method was used and, in addition, tree trunks were searched for resting moths. 42 species of moths from six families were found using both methods. The family Geometridae was predominant in terms of the numbers of individuals collected. Two geometrid species - Alsophila aescularia and Operophtera brumata - were defined as characteristic of the assemblage investigated. Late autumn and spring were richest in the numbers of species, whereas the species diversity was the lowest in mid-winter. Regression analysis showed that a temperature rise increased the species diversity of Geometridae but that rising air pressure negatively affected the abundance of Noctuidae. Key words: Lepidoptera, Geometridae, Noctuidae, autumn-spring activity, winter, phenology, atmospheric conditions, regression, Central Poland. INTRODUCTION The seasonal weather changes in a temperate climate have a great impact on poikilothermic animals, as they have a limited ability to regulate their body temperature. Thus, the earliest and most easily detectable response to climate change is an adjustment of species phenology (Huntley, 2007).