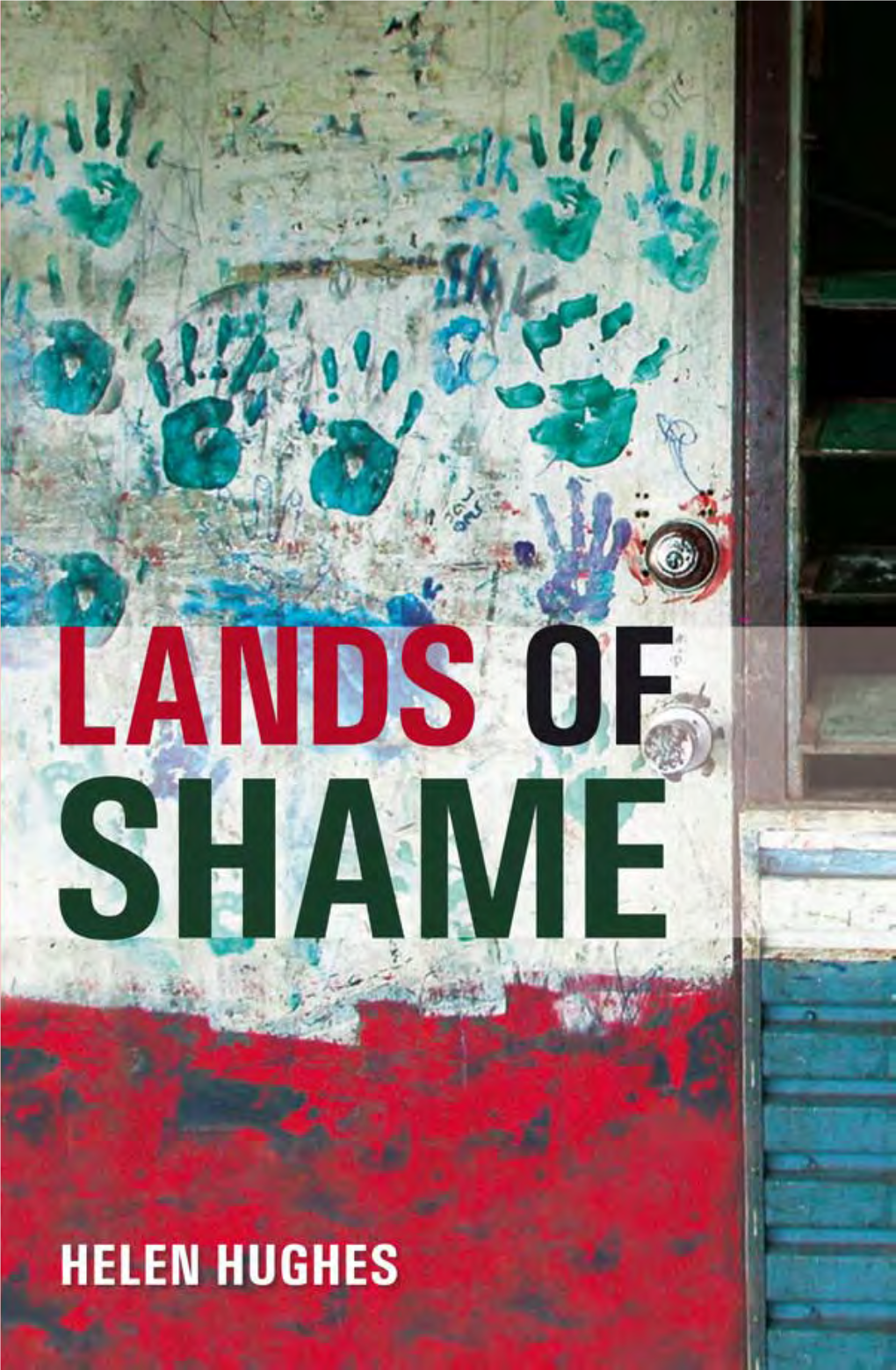

Lands of Shame: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander 'Homelands'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APPENDIX G Language Codes Queensland Hospital Admitted Patient Data Collection (QHAPDC) 2019-2020 V0.1

APPENDIX G Language Codes Queensland Hospital Admitted Patient Data Collection (QHAPDC) 2019-2020 V0.1 Appendix G Published by the State of Queensland (Queensland Health), 2019 This document is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au © State of Queensland (Queensland Health) 2019 You are free to copy, communicate and adapt the work, as long as you attribute the State of Queensland (Queensland Health). For more information contact: Statistical Services and Integration Unit, Statistical Services Branch, Department of Health, GPO Box 48, Brisbane QLD 4001, email [email protected]. An electronic version of this document is available at https://www.health.qld.gov.au/hsu/collections/qhapdc Disclaimer: The content presented in this publication is distributed by the Queensland Government as an information source only. The State of Queensland makes no statements, representations or warranties about the accuracy, completeness or reliability of any information contained in this publication. The State of Queensland disclaims all responsibility and all liability (including without limitation for liability in negligence) for all expenses, losses, damages and costs you might incur as a result of the information being inaccurate or incomplete in any way, and for any reason reliance was placed on such information. APPENDIX G – 2019-2020 v1.0 2 Contents Language Codes – Alphabetical Order ....................................................................................... 4 Language Codes – Numerical Order ......................................................................................... 31 APPENDIX G – 2019-2020 v1.0 3 Language Codes – Alphabetical Order From 1st July 2011 a new language classification was implemented in Queensland Health (QH). -

Djambawa Marawili

DJAMBAWA MARAWILI Date de naissance : 1953 Communauté artistique : Yirrkala Langue : Madarrpa Support : pigments naturels sur écorce, sculpture sur bois, gravure sur linoleum Nom de peau : Yirritja Thèmes : Yinapungapu, Yathikpa, Burrut'tji, Baru - crocodile, heron, fish, eagle, dugong Djambawa Marawili (born 1953) is an artist who has experienced mainstream success (as the winner of the 1996 Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art award Best Bark Painting Prize and as an artist represented in most major Australian institutional collections and several important overseas public and private collections) but for whom the production of art is a small part of a much bigger picture. Djambawa as a senior artist as well as sculpture and bark painting has produced linocut images and produced the first screenprint image for the Buku-Larr\gay Mulka Printspace. His principal roles are as a leader of the Madarrpa clan, a caretaker for the spiritual wellbeing of his own and other related clan’s and an activist and administrator in the interface between non-Aboriginal people and the Yol\u (Aboriginal) people of North East Arnhem Land. He is first and foremost a leader, and his art is one of the tools he uses to lead. As a participant in the production of the Barunga Statement (1988),which led to Bob Hawke’s promise of a treaty, the Royal Commission into Black Deaths in Custody and the formation of ATSIC , Djambawa drew on the sacred foundation of his people to represent the power of Yolngu and educate ‘outsiders’ in the justice of his people’s struggle for recognition. -

Presentation Tile

Authentic and engaging artist-led Education Programs with Thomas Readett Ngarrindjeri, Arrernte peoples 1 Acknowledgement 2 Warm up: Round Robin 3 4 See image caption from slide 2. installation view: TARNANTHI featuring Mumu by Pepai Jangala Carroll, 2015, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide; photo: Saul Steed. 5 What is TARNANTHI? TARNANTHI is a platform for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists from across the country to share important stories through contemporary art. TARNANTHI is a national event held annually by the Art Gallery of South Australia. Although TARNANTHI at AGSA is annual, biannually TARNANTHI turns into a city-wide festival and hosts hundreds of artists across multiple venues across Adelaide. On the year that the festival isn’t on, TARNANTHI focuses on only one feature artist or artist collective at AGSA. Jimmy Donegan, born 1940, Roma Young, born 1952, Ngaanyatjarra people, Western Australia/Pitjantjatjara people, South Australia; Kunmanara (Ray) Ken, 1940–2018, Brenton Ken, born 1944, Witjiti George, born 1938, Sammy Dodd, born 1946, Pitjantjatjara/Yankunytjatjara people, South Australia; Freddy Ken, born 1951, Naomi Kantjuriny, born 1944, Nyurpaya Kaika Burton, born 1940, Willy Kaika Burton, born 1941, Rupert Jack, born 1951, Adrian Intjalki, born 1943, Kunmanara (Gordon) Ingkatji, c.1930–2016, Arnie Frank, born 1960, Stanley Douglas, born 1944, Maureen Douglas, born 1966, Willy Muntjantji Martin, born 1950, Taylor Wanyima Cooper, born 1940, Noel Burton, born 1994, Kunmanara (Hector) Burton, 1937–2017, -

Handbook of Western Australian Aboriginal Languages South of the Kimberley Region

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Series C - 124 HANDBOOK OF WESTERN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL LANGUAGES SOUTH OF THE KIMBERLEY REGION Nicholas Thieberger Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Thieberger, N. Handbook of Western Australian Aboriginal languages south of the Kimberley Region. C-124, viii + 416 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1993. DOI:10.15144/PL-C124.cover ©1993 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. Pacific Linguistics is issued through the Linguistic Circle of Canberra and consists of four series: SERIES A: Occasional Papers SERIES c: Books SERIES B: Monographs SERIES D: Special Publications FOUNDING EDITOR: S.A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: T.E. Dutton, A.K. Pawley, M.D. Ross, D.T. Tryon EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B.W.Bender KA. McElhanon University of Hawaii Summer Institute of Linguistics DavidBradley H.P. McKaughan La Trobe University University of Hawaii Michael G. Clyne P. Miihlhausler Monash University University of Adelaide S.H. Elbert G.N. O'Grady University of Hawaii University of Victoria, B.C. KJ. Franklin KL. Pike Summer Institute of Linguistics Summer Institute of Linguistics W.W.Glover E.C. Polome Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Texas G.W.Grace Gillian Sankoff University of Hawaii University of Pennsylvania M.A.K Halliday W.A.L. Stokhof University of Sydney University of Leiden E. Haugen B.K T' sou Harvard University City Polytechnic of Hong Kong A. Healey E.M. Uhlenbeck Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Leiden L.A. -

FPA Legislation Committee Tabled Docu~Ent No. \

FPA Legislation Committee Tabled Docu~ent No. \, By: Mr~ C'-tn~:S AOlSC, Date: b IV\a,c<J..-. J,od.D , e,. t\-40.M I ---------- - ~ -- Australian Government National IndigeJrums Australlfans Agency OFFICIAL Chief Executive Officer Ray Griggs AO, CSC Reference: EC20~000257 Senator Tim Ayres Labor Senator for New South Wales Deputy Chair, Senate Finance and Public Administration Committee 6 March 2020 Re: Additional Estimates 2019-2020 Dear Senatafyres ~l Thank you for your letter dated 25 February 2020 requesting information about Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS) and Aboriginals Benefit Account (ABA) grants and unsuccessful applications for the periods 1 January- 30 June 2019 and 1 July 2019 (Agency establishment) - 25 February 2020. The National Indigenous Australians Agency has prepared the attached information; due to reporting cycles, we have provided the requested information for the period 1 January 2019 - 31 January 2020. However we can provide the information for the additional period if required. As requested, assessment scores are provided for the merit-based grant rounds: NAIDOC and ABA. Assessment scores for NAIDOC and ABA are not comparable, as NAIDOC is scored out of 20 and ABA is scored out of 15. Please note as there were no NAIDOC or ABA grants/ unsuccessful applications between 1 July 2019 and 31 January 2020, Attachments Band D do not include assessment scores. Please also note the physical location of unsuccessful applicants has been included, while the service delivery locations is provided for funded grants. In relation to ABA grants, we have included the then Department's recommendations to the Minister, as requested. -

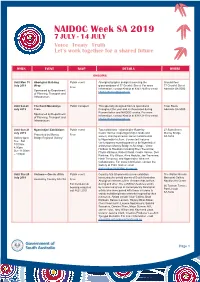

NAIDOC Week SA 2019 7 JULY - 14 JULY Voice

NAIDOC Week SA 2019 7 JULY - 14 JULY Voice . Treaty . Truth Let’s work together for a shared future WHEN EVENT RSVP DETAILS WHERE ONGOING Until Mon 15 Aboriginal Building Public event Aboriginal graphic design is covering the Ground floor July 2019 Wrap glass windows of 77 Grenfell Street. For more 77 Grenfell Street Free information, contact Khatija at 8343 2449 or email Adelaide SA 5000 Sponsored by Department [email protected] of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure Until Sat 20 The Kardi Munaintya Public transport This specially designed tram is operational Tram Route July 2019 Tram throughout the year and is showcased during Adelaide SA 5000 Reconciliation and NAIDOC weeks. For more Sponsored by Department information, contact Khatija at 8343 2449 or email of Planning, Transport and [email protected] Infrastructure Until Sun 21 Ngarrindjeri Exhibitions Public event Two exhibitions - Ngarrindjeri Ruwe by 27 Sixth Street July 2019 Cedric Varcoe maps Ngarrindjeri lands and Murray Bridge Presented by Murray Free waters, sharing ancestor stories fundamental SA 5253 Gallery open Bridge Regional Gallery to Ngarrindjeri culture. Connected features Tue - Sat contemporary weaving practices by Ngarrindjeri 10:00am – artists from Murray Bridge to Meningie, Victor 4:00pm Harbour to Raukkan including Ellen Trevorrow, Sun 11:00am Phyllis Williams, Robert Wuldi, Cedric Varcoe, Deb – 4:00pm Rankine, Elly Wilson, Alice Abdulla, Joe Trevorrow, Hank Trevorrow, and Ngarrindjeri Weavers Collaborators. For more information, contact the Gallery at 8539 1420 or email [email protected] Until Thu 25 Vietnam – One In, All In Public event Country Arts SA presents a new exhibition The Walter Nichols July 2019 honouring the untold stories of South Australian Memorial Gallery Hosted by Country Arts SA Free Aboriginal veterans of the Vietnam War, before, Nautilus Art Centre For Port Lincoln during and after. -

Annual Report 2011–12 Annual Report 2011–12 the National Gallery of Australia Is a Commonwealth (Cover) Authority Established Under the National Gallery Act 1975

ANNUAL REPORT 2011–12 ANNUAL REPORT 2011–12 The National Gallery of Australia is a Commonwealth (cover) authority established under the National Gallery Act 1975. Henri Matisse Oceania, the sea (Océanie, la mer) 1946 The vision of the National Gallery of Australia is the screenprint on linen cultural enrichment of all Australians through access 172 x 385.4 cm to their national art gallery, the quality of the national National Gallery of Australia, Canberra collection, the exceptional displays, exhibitions and gift of Tim Fairfax AM, 2012 programs, and the professionalism of our staff. The Gallery’s governing body, the Council of the National Gallery of Australia, has expertise in arts administration, corporate governance, administration and financial and business management. In 2011–12, the National Gallery of Australia received an appropriation from the Australian Government totalling $48.828 million (including an equity injection of $16.219 million for development of the national collection), raised $13.811 million, and employed 250 full-time equivalent staff. © National Gallery of Australia 2012 ISSN 1323 5192 All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Produced by the Publishing Department of the National Gallery of Australia Edited by Eric Meredith Designed by Susannah Luddy Printed by New Millennium National Gallery of Australia GPO Box 1150 Canberra ACT 2601 nga.gov.au/AboutUs/Reports 30 September 2012 The Hon Simon Crean MP Minister for the Arts Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister On behalf of the Council of the National Gallery of Australia, I have pleasure in submitting to you, for presentation to each House of Parliament, the National Gallery of Australia’s Annual Report covering the period 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2012. -

Spirit Festival Takes Centre Stage

Aboriginal Way Issue 48, Mar 2012 A publication of South Australian Native Title Services Spirit Festival takes centre stage Tandanya, the National Aboriginal Cultural Institute has hosted another successful Spirit Festival. Thousands of people attended, immersing themselves in Aboriginal and Islander culture. Left is Panjiti Lewis from Ernabella. For more photos from the Spirit Festival turn to pages 8 and 9. Photo supplied by Tandanya andRaymond Zada.Photosupplied Tandanya by Judges and magistrates have The Ripple Effect Supreme Court Judges and with assistance from Courts Administration Magistrates from Adelaide have Authority Aboriginal Programmes Manager taken steps to break down the Ms Sarah Alpers and Senior Aboriginal cultural barriers between Aboriginal Justice Officer Mr Paul Tanner. people and the legal system by The visit promoted cross-cultural spending time on the Anangu awareness between the judiciary and Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands. Aboriginal communities, and to improve Not only did 17 judges and magistrates understanding between the cultures spend five days and nights on the lands about law and justice matters. visiting communities but a DVD has been Justice Sulan said the trip was also in made of the trip so that others can learn keeping with Recommendation 96 of the from the experience. 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal The DVD is called The Ripple Effect and it Deaths in Custody. explains how decisions made by judges “…that recommendation calls on Australian and magistrates affect entire communities judiciary to make itself aware of Aboriginal hundreds of kilometres away. culture and practices through cultural The DVD was launched at a ceremony in the awareness programs and informal Above: Caption. -

Reflect Reconciliation Action Plan December 2019 – April 2021 Acknowledgement of Country Acknowledgement of Country

Reflect Reconciliation Action Plan December 2019 – April 2021 Acknowledgement of Country Acknowledgement of Country Artwork Acknowledgement QinetiQ acknowledges the Traditional Owners and Foreword by the Managing Director Custodians of the Australian land and pays its respects to their Elders both past and present. Our Business We acknowledge Reconciliation Australia for their insights and assistance in the development of this Reconciliation Action Plan. What is the Reconciliation Action Plan Our Reconciliation Action Plan Artwork Acknowledgement Our Partnerships / Current Activities RAP Champion Our Forward Journey The cover artwork, titled Two Ways Ngandi and group in the Roper River region of East Arnhem Wiradjuri (2019) was painted by Linda Huddleston Land through her father’s people and has cultural Relationships (Nungingi). ties with the Wiradjuri tribe of NSW through her mother’s people from the Talbragar people, Dubbo. This painting depicts Linda’s story as a little girl Respect growing up with her mother’s family in Dubbo, The Roper River Mission was established in NSW and also growing up with her father’s family 1908 and became a focal food and shelter point Opportunities Roper Ngukurr Far North East Arnhem Land. Linda for people within a radius of several hundred describes: “coming from my mother’s family you kilometres whose traditional way of life had only had one mum and dad, then in my father’s been severely disrupted. In 1968 the mission Governance people I had so many mothers and fathers, so I had reverted to Aboriginal control and its name to adjust to so many different ways.” changed to “Ngukurr”. -

Tjayiwara Unmuru Celebrate Native Title Determination

Aboriginal Way Issue 54, October 2013 A publication of South Australian Native Title Services Tjayiwara Unmuru celebrate native title determination Tjayiwara Unmuru Federal Court Hearing participants in SA’s far north. De Rose Hill achieves Australia’s first native title compensation determination Australia’s first native title The name of De Rose Hill will go down Under the Native Title Act, native title and this meant open communication compensation consent in Australian legal history for a number holders may be entitled to compensation between parties and of course determination was granted to of reasons. on just terms where an invalid act impacts overcoming the language barriers and on native title rights and interests. we thank the State for its cooperation the De Rose Hill native title “First, because you brought one of the for what was at times a challenging holders in South Australia’s early claims for recognition of your native Karina Lester, De Rose Hill Ilpalka process,” said Ms Lester. far north earlier this month. title rights over this country, and because Aboriginal Corporation chairperson you had the first hearing of such a claim said this is also a significant achievement Native title holder Peter De Rose said the The hearing of the Federal Court was in South Australia.” for the State, who played a key role in compensation determination was a better held at an important rock hole, Ilpalka, this outcome and have worked closely experience compared to the group’s fight on De Rose Hill Station. Now, again, you are leading the charge. with De Rose Hill Ilpalka Aboriginal for native title recognition which lasted This is the first time an award of Corporation through the entire process. -

First AIATSIS Summit Held in Adelaide

Issue 83, Winter 2021 A publication by South Australian Native Title Services www.nativetitlesa.org Ngarrindjeri elder Major ‘Moogy’ Sumner AM performs a smoking ceremony on the banks of the Karrawirra Parri (River Torrens) for delegates on Day 3 of the Summit. Kaurna elder Jeffrey Newchurch sits to the left. First AIATSIS Summit held in Adelaide This year the Australian Institute of The AIATSIS Summit was held from was a chance to reconnect and celebrate academics, and legal experts. It was an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander 31 May to 4 June at the Adelaide Mabo Day and National Reconciliation opportunity to strengthen Aboriginal and Studies (AIATSIS) combined the biennial Convention Centre with hosts Kaurna Week as a community on Kaurna land. Torres Strait Islander cultures, knowledge, and governance following the isolation Indigenous Research Conference and Yerta Aboriginal Corporation (KYAC) and Over 900 delegates attended across the brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. Native Title Conference to make the co-convenor South Australian Native five days which included presentations first AIATSIS Summit. Title Services (SANTS). The Summit and workshops led by community leaders, Continued on page 2 Inside: Nauo and Wirangu agree on consent determinations 4 New carbon farming Code recognises native title rights 5 Kaurna cultural burn makes history 6 Book launch: Sorry and Beyond – Healing the Stolen Generations 10 First AIATSIS Summit held in Adelaide Continued from page 1 Bunuba woman June Oscar AO, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander What we heard at the Social Justice Commissioner, shared AIATSIS Summit the Wiyi Yani U Thangani (Women’s Voices) Aboriginal Commissioner for Children Report. -

Eyre and Western Planning Region Vivonne Bay Island Beach Date: February 2020 Local Government Area Other Road

Amata Kalka Kanpi Pipalyatjara Nyapari Pukatja Yunyarinyi Umuwa Kaltjiti Indulkana Mimili Watarru Mintabie Marla S T U A R T Oodnadatta H W Y Cadney Park PASTORAL UNINCORPORATED AREA William Creek Coober Pedy MARALINGA TJARUTJA S Oak Valley T U A R T H W Y Olympic Dam Andamooka Village Roxby Downs Tarcoola S Y TU Kingoonya W AR T H Glendambo H W M Y A PASTORAL D C I P M UNINCORPORATED Y L O Woomera AREA Pimba Nullarbor Roadhouse Yalata EYRE HWY Border Village Nundroo Bookabie Koonibba Coorabie EYRE HWY Penong CEDUNA Fowlers Bay Denial Bay Ceduna Mudamuckla Nunjikompita Smoky Bay F LI Wirrulla Stirling ND E North RS Petina Yantanabie H W Y Courela Port Augusta Haslam E Y Chilpenunda R Cungena E H W Y Blanche STREAKY L EAK D Poochera Harbor TR Y R I S Y N BA Iron Knob C BAY Chandada IR O Minnipa O L F N N Streaky Bay LIN DE K R Buckleboo WHYALLA N H S O Yaninee B W H Y W Iron Baron RD Calca Y Sceale Bay WUDINNA Pygery KIMBA Mullaquana Baird Bay Wudinna Whyalla Point Lowly Colley Mount Damper Kimba Port Kenny EYRE H Kyancutta W Y Warramboo Koongawa Talia Waddikee Venus Bay Y W Kopi H C L Mount Wedge E N L Darke Peak V BIRDSEYE E O H C WY Mangalo Bramfield Lock R IN D FRANKLINL BIR Kielpa Y D SEYE W HWY HARBOUR F ELLISTON H LI Elliston ND Cleve E D Cowell RS Murdinga Rudall O HW T Y Sheringa Alford Tooligie CLEVE Y Wharminda W H Wallaroo Paskeville LN Arno Bay Kadina O Karkoo C Mount Hope TUMBY IN L Moonta Port Neill Kapinnie Yeelanna BAY Agery LOWER EYRE Ungarra PENINSULA Cummins Lipson Arthurton Tumby Bay Balgowan Coulta Koppio Maitland