An Abstract of the Thesis Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

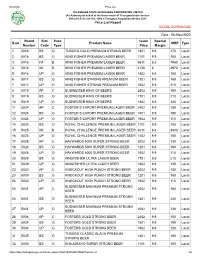

Price List Report EXCEL DOWNLOAD Date : 06-May-2020 S.No Brand

5/6/2020 Price List TELANGANA STATE BEVERAGES CORPORATION LIMITED (An Authority on behalf of the Government of Telangana Under Section 68A of A.P. Excise Act, 1968 )( Telangana Adaptation) Orders 2015 Price List Report EXCEL DOWNLOAD Date : 06-May-2020 Brand Size Pack Issue Special S.no Product Name MRP Type Number Code Type Price Margin 1 5006 BS G TUBORG GOLD PREMIUM STRONG BEER 1301 9.9 170 Local 2 5016 BS G KING FISHER PREMIUM LAGER BEER 1101 9.9 150 Local 3 5016 FK B KING FISHER PREMIUM LAGER BEER 6611 6.8 7960 Local 4 5016 KK B KING FISHER PREMIUM LAGER BEER 4120 6 4970 Local 5 5016 UP G KING FISHER PREMIUM LAGER BEER 1402 9.9 100 Local 6 5017 BS G KING FISHER STRONG PREMIUM BEER 1201 9.9 160 Local 7 5017 UP G KING FISHER STRONG PREMIUM BEER 1602 9.9 110 Local 8 5019 AP C BUDWEISER KING OF BEERS 2602 9.9 160 Local 9 5019 BS G BUDWEISER KING OF BEERS 1701 9.9 210 Local 10 5019 UP G BUDWEISER KING OF BEERS 1802 9.9 120 Local 11 5024 AP C FOSTER S EXPORT PREMIUM LAGER BEER 2402 9.9 150 Local 12 5024 BS G FOSTER S EXPORT PREMIUM LAGER BEER 1501 9.9 190 Local 13 5024 UP G FOSTER S EXPORT PREMIUM LAGER BEER 1602 9.9 110 Local 14 5025 BS G ROYAL CHALLENGE PREMIUM LAGER BEER 1101 9.9 150 Local 15 5025 KK B ROYAL CHALLENGE PREMIUM LAGER BEER 4011 6.8 4840 Local 16 5025 UP G ROYAL CHALLENGE PREMIUM LAGER BEER 1402 9.9 100 Local 17 5028 AP C HAYWARDS 5000 SUPER STRONG BEER 2002 9.9 130 Local 18 5028 BS G HAYWARDS 5000 SUPER STRONG BEER 1201 9.9 160 Local 19 5028 UP G HAYWARDS 5000 SUPER STRONG BEER 1602 9.9 110 Local 20 5029 BS G KINGFISHER -

Crc - Liquor List

2701 W Howard Street Chicago, IL 60645-1303 PH: 773.465.3900 Fax: 773.465.6632 Rabbi Sholem Fishbane Kashruth Administrator Items listed as "Recommended" do not require a kosher symbol unless they are marked with a star (*) This list is updated regularly and should be considered accurate until December 31, 2013 cRc - Liquor List Bar Stock Items Bar Stock Items Bar equipment (strainers, shot measures, blenders, stir Other rods, shakers, etc.) used with non-kosher products Olives - Green should be properly cleaned and/or kashered prior to Require Certification use with kosher products. Onions - Pearl Canned or jarred require certification Recommended Coco Lopez OU* Beer Daily's OU* All unflavored beers with no additives are acceptable, OU* Holland House even without Kosher certification. This applies to both Jamaica John cRc* American and imported beers, light, dark and non- Jero OK* alcoholic beers. Mr & Mrs T OU or OK* Many breweries produce specialty brews that have Rose's - Grenadine OU* additives; please check the label and do not assume Rose's - Lime OU* that all varieties are acceptable. Furthermore, beers known to be produced at microbreweries, pub K* Tabasco - Hot Pepper Sauce breweries, or craft breweries require certification. Underberg - Herb Mix for Underberg OU* Natural Herb Bitters Recommended Other 800 - Ice Beer OU Bitters Anheuser-Busch - Redbridge Gluten Require Certification Free Coconut Milk Aspen Edge - Lager OU Requires Certification Blue Moon - Belgian White Ale OU* Cream of Coconut Blue Moon - Full Moon Winter Ale -

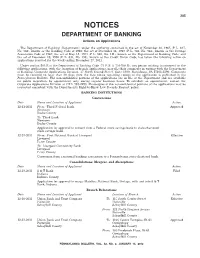

NOTICES DEPARTMENT of BANKING Actions on Applications

205 NOTICES DEPARTMENT OF BANKING Actions on Applications The Department of Banking (Department), under the authority contained in the act of November 30, 1965 (P. L. 847, No. 356), known as the Banking Code of 1965; the act of December 14, 1967 (P. L. 746, No. 345), known as the Savings Association Code of 1967; the act of May 15, 1933 (P. L. 565, No. 111), known as the Department of Banking Code; and the act of December 19, 1990 (P. L. 834, No. 198), known as the Credit Union Code, has taken the following action on applications received for the week ending December 27, 2011. Under section 503.E of the Department of Banking Code (71 P. S. § 733-503.E), any person wishing to comment on the following applications, with the exception of branch applications, may file their comments in writing with the Department of Banking, Corporate Applications Division, 17 North Second Street, Suite 1300, Harrisburg, PA 17101-2290. Comments must be received no later than 30 days from the date notice regarding receipt of the application is published in the Pennsylvania Bulletin. The nonconfidential portions of the applications are on file at the Department and are available for public inspection, by appointment only, during regular business hours. To schedule an appointment, contact the Corporate Applications Division at (717) 783-2253. Photocopies of the nonconfidential portions of the applications may be requested consistent with the Department’s Right-to-Know Law Records Request policy. BANKING INSTITUTIONS Conversions Date Name and Location of Applicant Action 12-21-2011 From: Third Federal Bank Approved Newtown Bucks County To: Third Bank Newtown Bucks County Application for approval to convert from a Federal stock savings bank to state-chartered stock savings bank. -

Abbey/Trappist Dubblel Abbey / Trappist Tripel / Triple Altbier Altbier

Abbey/Trappist Dubblel Perhaps the only feature all Abbey/Trappist ales have in common is bottle conditioning. In addition, these ales tend to have a big, dense, and creamy head; a complex, yeasty, fruity, and estery flavor and aroma; and sometimes a slightly sweet finish. Especially the stronger, well-aged variations often have notes of sour cherry and oak. Abbey / Trappist Tripel / Triple For a general style description of Abbey / Trappist Ale, see Abbey / Trappist Dubbel. The base malt for any Abbey/Trappist brew is usually Pilsner or Pale Ale malt. Traditionally, some of the brew's fermentables and thus alcohol come from rock candy, sugar syrup, or regular table sugar added to the kettle. Altbier Altbier is an unusual, cool-fermented, lagered ale. It is copper-colored, hop-accented and clean tasting. It should have virtually no roasted notes and is best made with plenty of Munich malt. The flavor profile of Altbier is greatly influenced by the yeast. While relatively warm-fermenting British ale yeast gives a brew plenty of fruity complexity, cool-fermenting specialty Altbier yeasts do exactly the opposite. The mouthfeel ought to be light and clean, like that of a Dunkel lager, but with a touch more attenuation and a more hop-aromatic finish. Altbier, Westphalian From the descriptions available to us today, the early medieval ales of the region, such as the Brunswick Mumme, were fairly heavy, darkish, syrupy ales-probaly from smoky malts and low-attenuating yeasts. While the copper Altbiers of Düsseldorf and their blond Kölsch cousins from Cologne have largely shed their wheaten heritage, in Munster and environs, the Keutebier metamorphosed into a type of Altbier that retained much of old wheaten creaminess. -

Table of Content

WOLFGANG KUNZE TECHNOLOGY Brewing and Malting Edited by Olaf Hendel Chapter11 co-written by Dr. Hans-Jürgen Manger 6th English edition Published by The chapters at a glance Contents Beer – the oldest drink 21 Beer – The Oldest Fermented Drink 1 Raw Materials 35 for the Common People ........................... 25 2 Malt Production 109 3 Wort Production 199 1 Raw Materials ................................ 39 4 Beer Production 1.1 Barley .............................................. 39 (Fermentation, Maturation, Filtration) 367 1.1.1 Barley Cultivation and Varieties ........ 39 5 Filling the Beer 537 - Barley Cultivation .......................... 39 6 Cleaning and Disinfection 691 - Barley Varieties .............................. 40 7 Finished Beer 707 1.1.2 Barley Cultivation ............................. 41 8 Small Scale Brewing 763 1.1.3 Structure of the Barley Grain ........... 42 9 Waste Disposal and the Environment 783 - External Structure .......................... 42 10 Energy Management in the Brewery - Internal Structure ........................... 42 and Malting 797 1.1.4 Composition and Properties 11 Automation and Plant Planning 849 of the Components ......................... 44 - Carbohydrates ............................... 44 - Proteins ......................................... 48 - Fats (Lipids) ................................... 50 - Minerals ........................................ 51 - Other Substances .......................... 52 - Barley Enzymes .............................. 53 1.1.5 Barley Evaluation ............................. -

Copy of Beer Book Fall 2017.Xlsx

Beer Book June, 2017Beer Book Fall 2017 Domestic Page Imported Maine 2 Page New Hampshire 2-3 Belgium 5-6 Massachusetts 3 Brazil 6 Vermont 3 Canada 6 California 3 Denmark 6 Colorado 4 England 6 Idaho 4 France 6 Louisiana 4 Germany 6- Michigan 4 7 New York 4 Ireland 7 Nevada 4 Italy 7 Ohio 4 Japan 7 Oregon 4 Norway 7 Switzerland 7 Gluten Free 8 Our Keg list and most up to date selections are released every Monday via our newsletter. Sign up at www.marinerbeverages.com. We strive to provide the most accurate information possible, prices listed with the Bureau of LiQuor Enforcement supersede any typographical errors in this book. Brewery Name Btl Size Pack Size Notes New England MAINE Dirigo Brewing Lager 16oz 6/4pks Munich Helles. Smooth and easy drinking craft cross-over. Dirigo Brewing *** New England Pale Lager - NEPAL 16oz 6/4pks Hoppy Lager. Rotating local ingredients. ***multiple releases, not always available. Biddeford, ME - Artisinal Brewery, see keg list for current selections Rising Tide Brewing Back Cove Pilsner 16oz 6/4pks North German Style Pilsner Rising Tide Brewing Cutter 16oz 6/4pks Imperial IPA Rising Tide Brewing Daymark 12oz 6/4pks American Pale Ale Rising Tide Brewing Ishmael 12oz 6/4pks American Copper Ale Rising Tide Brewing Barrel Aged Nikita 500ml 12 Bourbon-barrel aged Rye Russian Imperial Stout Rising Tide Brewing Pisces 16oz 6/4pks Gose Rising Tide Brewing Waypoint 12oz 6/4pks Coffee Porter Rising Tide Brewing Zephyr 12oz 6/4pks IPA Portland, ME - Artisinal brewery, see keg list for current selections Foundation Brewing *** Afterglow 16oz 6/4pks Maine American IPA ABV 7% Foundation Brewing *** Coffee Burnside 16oz 6/4pks Coffee, Brown Ale Foundation Brewing *** Cosmic Bloom 16oz 6/4pks Hoppy American Ale 5.8%, coming mid June Foundation Brewing *** Epiphany 16oz 6/4pks Maine IPA-99pts Beer Advocate. -

Malt Beverage Formulation

Malt Beverage Formulation Presented by Michael Warren, Formulation Specialist Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau Specific Regulatory Authority for Malt Beverages • Alcohol Beverage Labeling Act of 1988 – 27 U.S.C. 213 et. Seq. – 27 CFR part 16 • Federal Alcohol Administration Act – 27 U.S.C. 205 – 27 CFR part 7 – Malt Beverages • Internal Revenue Code – 26 U.S.C. Chapter 51 – 27 CFR part 25 – Beer 2 How many formulas do we review per year? We received approximately 4246 malt beverage formula submissions in FY 2014 Of which, 45-50% are returned for correction!! 3 Formulation Team Mission • To properly Class and type the product to ensure the proper taxes are affixed. • To ensure all products are produced in accordance with all regulations making for an even “playing field” across the industry. • Ensure all products are made with safe ingredients and production processes by collaborating closely with the FDA. 4 Where can I go to find out if my Beer requires a Pre-Cola Evaluation? 5 Important Guidance Circulars • Industry Circular • TTB Ruling 2014-4 2007-4 6 Industry Circular 2007-4 • Is a road map to be used to determine if your product requires a Pre-Cola Evaluation 7 What types of products require Pre-Cola Evaluation? • Malt Beverage Specialties/Flavor ed Malt Beverages • Ice Beer • Alcohol Free Malt Beverages • IRC Beers 8 Malt Beverage Specialties • Malt beverage Specialty products are Beers that contain non exempted flavoring and coloring components and/or compounded flavors. 9 Release of TTB Ruling 2014-4 • Was released in response to the brewing industry submitting a request to exempt from formula requirements imposed by TTB regulations at 27 CFR 25.55, malt beverages made with honey, certain fruits, certain spices, and certain food ingredients. -

Bière : Les Quatre Multinationales Qui Se Cachent Derrière Des Centaines De Marques

Bière : les quatre multinationales qui se cachent derrière des centaines de marques Le Monde.fr | 08.10.2015 à 14h21 • Mis à jour le 08.10.2015 à 17h31 | Par Mathilde Damgé (/journaliste/mathilde- damge/) A l’image de Munich, capitale allemande de la bière, Paris a décidé d’organiser sa première Oktoberfest, qui commence jeudi 8 octobre. Une opération très « marketing » (avec un prix d’entrée à 35 euros), à l’image d’un marché très concentré en dépit des centaines de marques proposées dans les bars, restaurants et grandes surfaces aux quatre coins de la planète . Et la tendance à la concentration pourrait s’accélérer : le numéro deux mondial de la bière SABMiller a rejeté mercredi une nouvelle offre d’achat de plus de 90 milliards d’euros présentée par son rival, le numéro un AB InBev, visant à créer un mastodonte du secteur mariant la Stella Artois et la Pilsner Urquell. Lire aussi : SABMiller rejette l’offre à 92 milliards d’euros du géant de la bière AB InBev (/entreprises/article/2015/10/07/brasseurs-ab-inbev-releve-son-offre-d-achat-sur- sabmiller_4783951_1656994.html) Les quatre leaders mondiaux, AB InBev, suivi de SABMiller, de Heineken et de Carlsberg, brassent près de la moitié de la bière mondiale et exploitent près de 800 marques à eux seuls. Ci-dessous, les marques exploitées par le néerlandais Heineken (18,4 milliards d’euros de chiffre d’affaires en 2012), le belge Anheuser-Busch InBev (29 milliards d’euros de chiffre d’affaires en 2012), le britannique SABMiller (25,42 milliards d’euros de chiffre d’affaires en 2012) et le danois Carlsberg (9 milliards d’euros de chiffre d’affaires en 2012). -

Flight Night Happy Hour

GOOD PEOPLE DRINK GOOD BEER DRAFTSANDIEGO.COM $12 EACH BABY GREENS $14 winter pears, spiced almonds, citrus segments, kale, vanilla vinaigrette INTERNATIONAL MULE OF MYSTERY lime juice, angostura bitters, ginger beer AHI POKE SALAD $15 {moscow ketel one} quinoa, pickled cucumber+wakame, avocado, chukka {irish jameson} {dixie wild turkey 81} {baja cazadores blanco} STEAK SALAD $16 {cali fugu small batch vodka by cutwater} roasted beets, crispy potatoes, pears, ST PETE red wine, blue cheese angels envy rye whiskey, lagavulin scotch, simple $ syrup, house sweet and sour, pineapple juice THE CALIFORNIAN CHOP 15 crisp romaine, bacon, tomato, black beans, GINGER FOR SGT PEPPER chicken, tortilla strips, cheddar cheese, rum haven coconut rum, fresh cucumber avocado dressing and basil, agave honey ginger syrup, pineapple juice, topped with fresh pepper MUSTARD DUSTED PRETZEL BITES $8 PURPLE PEOPLE EATER honey mustard patron silver tequila, simple syrup, black cherry, lemon, soda SHREDDED BEEF NACHOS $17 cheddar cheese, black beans, jalapeños, DRAFT TAI guacamole,verde salsa cruda, lime cream, bacardi cuatro anjeo rum, fresh orange and We feature artisanal rustic breads. Hand helds pico de gallo, queso fresco pineapple juice, orgeat syrup, dark rum float served with a choice of french fries or side salad. “SOUTH MISSION CADDY” SPINACH - ARTICHOKE DIP $14 TOP SHELF CLASSIC MARGARITA grilled pita, tortilla chips DRAFT BURGER $16 espolon silver tequila, fresh lime, house made lettuce, tomato, onion, $ sweet and sour, grand mariner float GRILLED PITA -

Department of the Treasury Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau

Monday, January 3, 2005 Part III Department of the Treasury Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau 27 CFR Parts 7 and 25 Flavored Malt Beverage and Related Regulatory Amendments (2002R–044P); Final Rule VerDate jul<14>2003 15:07 Dec 30, 2004 Jkt 205001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\03JAR3.SGM 03JAR3 194 Federal Register / Vol. 70, No. 1 / Monday, January 3, 2005 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY III. Discussion of Specific Proposals in TTB A. Information Quality Act Notice No. 4 B. ‘‘Alcohol is Alcohol’’ Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade A. Standard for Added Alcohol and C. Marketing of FMBs to Underage Bureau Alcohol from Fermentation Drinkers B. Proposed 0.5% Added Alcohol by D. More Explicit Labeling of FMBs Volume Standard for ‘‘Beer’’ under the E. Establishing Another Category of 27 CFR Parts 7 and 25 IRC Alcohol Beverages [TTB T.D.–21; Re: TTB Notice No. 4] C. Proposed 0.5% Added Alcohol by F. Other Comments Volume Standard for Malt Beverages XIV. Implementation Dates RIN 1513–AA12 under the FAA Act A. Effective Date for Compliance with the D. Alternative 51/49 (Majority) Alcohol New Added Alcohol Standard Flavored Malt Beverage and Related Standard B. Effect on Products in the Marketplace Regulatory Amendments (2002R–044P) E. Proposed Alcohol Content Labeling C. Additional TTB Comment on the Statement for Flavored Malt Beverages Effective Date AGENCY: Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and F. Use of Distilled Spirits Terms in Malt XV. Comments on the Proposed Regulatory Trade Bureau, Treasury. -

This Winter, Warm up at Iron Hill Chestnut Hill with Seasonal Beer Releases and a Festive Brewmaster’S Dinner

(Head Brewer Paul Rutherford) FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Profile Public Relations CONTACT: Jennie Hatton or James Narog (215) 985-2106/ www.profilepr.com / @ProfileTip THIS WINTER, WARM UP AT IRON HILL CHESTNUT HILL WITH SEASONAL BEER RELEASES AND A FESTIVE BREWMASTER’S DINNER CHESTNUT HILL, PA – This month, head brewer Paul Rutherford of Iron Hill Brewery & Restaurant (8400 Germantown Avenue, 215-948-5600) will host two exciting beer-driven events: his Fire & Ice Beer Release Party, featuring two “fire-inspired” and two “ice-inspired” original new beers; and a seasonal Brewmaster’s Dinner featuring wintry beers and hearty, comforting cuisine. These events are a perfect opportunity for new King of the Hill members to get to know their head brewer, and also a great time for would-be members to enroll in the extravagant new rewards program for Iron Hill fans, introduced in late 2012. “During the winter months, we love to stay warm with full-bodied beers and rich comfort foods,” says Rutherford. “Our Fire & Ice Release Party and Brewmaster’s Dinner are perfect ways for our guests to join us and celebrate our favorite things: great food and great beer.” Fire & Ice Release Party On Friday, January 11 from 6 p.m. until 9 p.m., Rutherford will host the Fire & Ice Release Party, featuring four special beers: Fire-Inspired Smoked Weizenbock, an amber-colored, full-bodied ale with banana and clove flavors and smoked character from malt smoked on beechwood chips; Fire-Inspired Rauchbier, a Bamburg, Germany-style amber lager made with beechwood smoked malt for a smoky aroma and flavor; Ice-Inspired Rasputin’s Revenge, a very special version of their full-bodied stout; and Ice- Inspired Hopsicle, a higher gravity version of an American IPA brewed entirely with pilsner malt and the Japanese hop variety Sorachi Ace, plus citrus-y and pine-y American hops. -

Beverages Variety Packs

Brick 10000142: Alcohol Making Kits Definition Includes any products that can be described/observed as an alcoholic drink making kit. These products are total units that include all the necessary ingredients and equipment required to brew various flavours of beer, wine or spirits. Excludes products such as Alcohol Making Accessories sold separately, Non–Alcoholic Drink Making Kits and Pre–Made Alcohol. Type of Alcohol Making Kit (20000004) Attribute Definition Indicates, with reference to the product branding, labelling or packaging the descriptive term that is used by the product manufacturer to identify a particular type or variety of alcohol making kit. Attribute Values BEER KIT (30000309) SPIRIT KIT (30002832) UNIDENTIFIED (30002518) LIQUEUR KIT (30003009) UNCLASSIFIED (30002515) WINE KIT (30002626) Page 1 of 155 Brick 10000143: Alcohol Making Supplies Definition Includes any products that can be described/observed as alcoholic drink making supplies; extra or replacement components for alcohol making kits or components for home put together kits. These products are individual pieces of hardware such as, siphons and fermentation locks and separately packaged ingredients such as brewers yeast. These products can either be disposable or re–usable. Excludes products such as Alcohol Making Kits and Pre–Made Alcohol. Type of Alcohol Making Supply (20000005) Attribute Definition Indicates, with reference to the product branding, labelling or packaging the descriptive term that is used by the product manufacturer to identify a particular