Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 55. MALT LIQUOR and WINE WHOLESALE LICENSEES

MRS Title 28-A, Chapter 55. MALT LIQUOR AND WINE WHOLESALE LICENSEES CHAPTER 55 MALT LIQUOR AND WINE WHOLESALE LICENSEES §1401. Wholesale licenses 1. Issuance of licenses. The bureau may issue licenses under this section for the sale and distribution of malt liquor, wine and fortified wine at wholesale. [PL 2013, c. 476, Pt. A, §29 (AMD).] 2. Fees. Except as provided in subsection 4, the fee for a wholesale license is: A. Six hundred dollars for the principal place of business; and [PL 1987, c. 45, Pt. A, §4 (NEW).] B. Six hundred dollars for each additional warehouse maintained by the wholesale licensee, but not located at the principal place of business. [PL 1987, c. 342, §109 (AMD).] [PL 1987, c. 342, §109 (AMD).] 3. Term of wholesale license. Except as provided in subsection 4, a wholesale license is effective for one year from the date of issuance. [PL 1987, c. 45, Pt. A, §4 (NEW).] 4. Temporary permits. The bureau may issue special permits, upon application in writing, for the temporary storage of malt liquor or wine under terms and upon conditions prescribed by the bureau. [PL 1997, c. 373, §123 (AMD).] 5. Qualifications. The bureau may not issue a wholesale license to an applicant unless: A. If the applicant is a person, the applicant has been a resident of the State for at least 6 months; or [PL 1987, c. 45, Pt. A, §4 (NEW).] B. If the applicant is a corporation, the applicant has conducted business in this State for at least 6 months. [PL 1987, c. -

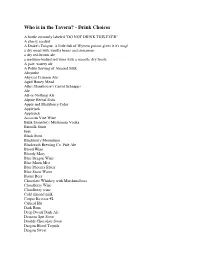

Drink Choices

Who is in the Tavern? - Drink Choices A bottle curiously labeled "DO NOT DRINK THIS EVER" A cherry cordial A Drake's Tongue. A little dab of Wyvern poison gives it it's zing! a dry mead with vanilla beans and cinnamon a dry red-brown ale a medium-bodied red wine with a smooth, dry finish A pale, watery ale A Polite Serving of Almond Milk Absynthe Abyssal Crimson Ale Aged Honey Mead Albis Shinehouse's Carrot Schnapps Ale All-or-Nothing Ale Alpine Herbal Soda Apple and Blackberry Cider Applejack Applejack Assassin Vine Wine Balik Stonefist's Mushroom Vodka Batmilk Stout beer Black Stout Blackberry Moonshine Blackwish Brewing Co. Pale Ale Blood Wine Bloody Mary Blue Dragon Wine Blue Moon Mist Blue Phoenix Elixir Blue Snow Water Butter Beer Chocolate Whiskey with Marshmallows Cloudberry Wine Cloudberry wine Cold almond milk Corpse Reviver #2 Critical Hit Dark Rum Deep Dwarf Dark Ale Demons Spit Stout Double Chocolate Stout Dragon Blood Tequila Dragon Sweat Dragon's Breath Ginger Beer Dragon's Breath Liquer Drambuie Dry red wine with sugared fruit slices. Dry white wine, aged in oak Dwarven Ale Dwarven Stout Elderblossom Wine Eleven Pear Cider from Imratheon Elorian Sprite Wine Elven Honey Mead Elven Pale Ale Elverquist (rare elven wine) Elvish Mint Tea Elvish Pale Ale Emerald Dream (absinthe) Fermented Owlbear Blood Firefly Ale -- For when you want to have a healthy glow about you. Firewine Five Foot's Frothingslosh Flametongue-Hellfire Pepper Porter fragrant mug of hot chamomile tea Ghost pepper pineapple juice Gimlet Ginger Scald Gnoll Booger -

The Blurring of Alcohol Categories (PDF)

4401 Ford Avenue, Suite 700, Alexandria, VA 22302-1433 Tel: (703) 578-4200 Fax: (703) 850-3551 www.nabca.org The Blurring of Alcohol Categories The Blurring of Alcohol Categories William C. Kerr, Ph.D. Deidre Patterson, M.P.H. Thomas K. Greenfield, Ph.D. Alcohol Research Group Prepared for the National Alcohol Beverage Control Association (NABCA) June 2013 National Alcohol Beverage Control Association. ©All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. TABLE OF CONTENTS Drink Alcohol Content......................................................1 Differential regulation and taxation by beverage type........2 Defining beer, wine and spirits products: Current definitions and recent changes........................7 Beer........................................................................7 Wine....................................................................10 Spirits..................................................................13 New products, especially flavored malt beverages with high alcoholic strength, have complicated beverage type definitions for both consumers and regulators.............................15 New and older products that blur beverage type definitions.........................................................15 More diverse beer products ...........................................15 What forces are driving -

A Temperate and Wholesome Beverage: the Defense of the American Beer Industry, 1880-1920

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 7-3-2018 A Temperate and Wholesome Beverage: the Defense of the American Beer Industry, 1880-1920 Lyndsay Danielle Smith Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smith, Lyndsay Danielle, "A Temperate and Wholesome Beverage: the Defense of the American Beer Industry, 1880-1920" (2018). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4497. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6381 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. A Temperate and Wholesome Beverage: The Defense of the American Beer Industry, 1880-1920 by Lyndsay Danielle Smith A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: Catherine McNeur, Chair Katrine Barber Joseph Bohling Nathan McClintock Portland State University 2018 © 2018 Lyndsay Danielle Smith i Abstract For decades prior to National Prohibition, the “liquor question” received attention from various temperance, prohibition, and liquor interest groups. Between 1880 and 1920, these groups gained public interest in their own way. The liquor interests defended their industries against politicians, religious leaders, and social reformers, but ultimately failed. While current historical scholarship links the different liquor industries together, the beer industry constantly worked to distinguish itself from other alcoholic beverages. -

Beer and Malt Handbook: Beer Types (PDF)

1. BEER TYPES The world is full of different beers, divided into a vast array of different types. Many classifications and precise definitions of beers having been formulated over the years, ours are not the most rigid, since we seek simply to review some of the most important beer types. In addition, we present a few options for the malt used for each type-hints for brewers considering different choices of malt when planning a new beer. The following beer types are given a short introduction to our Viking Malt malts. TOP FERMENTED BEERS: • Ales • Stouts and Porters • Wheat beers BOTTOM FERMENTED BEERS: • Lager • Dark lager • Pilsner • Bocks • Märzen 4 BEER & MALT HANDBOOK. BACKGROUND Known as the ‘mother’ of all pale lagers, pilsner originated in Bohemia, in the city of Pilsen. Pilsner is said to have been the first golden, clear lager beer, and is well known for its very soft brewing water, which PILSNER contributes to its smooth taste. Nowadays, for example, over half of the beer drunk in Germany is pilsner. DESCRIPTION Pilsner was originally famous for its fine hop aroma and strong bitterness. Its golden color and moderate alcohol content, and its slightly lower final attenuation, give it a smooth malty taste. Nowadays, the range of pilsner beers has extended in such a way that the less hopped and lighter versions are now considered ordinary lagers. TYPICAL ANALYSIS OF PILSNER Original gravity 11-12 °Plato Alcohol content 4.5-5.2 % volume C olor6 -12 °EBC Bitterness 2 5-40 BU COMMON MALT BASIS Pale Pilsner Malt is used according to the required specifications. -

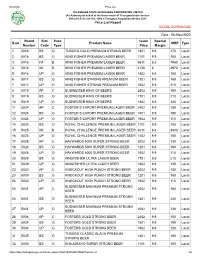

Price List Report EXCEL DOWNLOAD Date : 06-May-2020 S.No Brand

5/6/2020 Price List TELANGANA STATE BEVERAGES CORPORATION LIMITED (An Authority on behalf of the Government of Telangana Under Section 68A of A.P. Excise Act, 1968 )( Telangana Adaptation) Orders 2015 Price List Report EXCEL DOWNLOAD Date : 06-May-2020 Brand Size Pack Issue Special S.no Product Name MRP Type Number Code Type Price Margin 1 5006 BS G TUBORG GOLD PREMIUM STRONG BEER 1301 9.9 170 Local 2 5016 BS G KING FISHER PREMIUM LAGER BEER 1101 9.9 150 Local 3 5016 FK B KING FISHER PREMIUM LAGER BEER 6611 6.8 7960 Local 4 5016 KK B KING FISHER PREMIUM LAGER BEER 4120 6 4970 Local 5 5016 UP G KING FISHER PREMIUM LAGER BEER 1402 9.9 100 Local 6 5017 BS G KING FISHER STRONG PREMIUM BEER 1201 9.9 160 Local 7 5017 UP G KING FISHER STRONG PREMIUM BEER 1602 9.9 110 Local 8 5019 AP C BUDWEISER KING OF BEERS 2602 9.9 160 Local 9 5019 BS G BUDWEISER KING OF BEERS 1701 9.9 210 Local 10 5019 UP G BUDWEISER KING OF BEERS 1802 9.9 120 Local 11 5024 AP C FOSTER S EXPORT PREMIUM LAGER BEER 2402 9.9 150 Local 12 5024 BS G FOSTER S EXPORT PREMIUM LAGER BEER 1501 9.9 190 Local 13 5024 UP G FOSTER S EXPORT PREMIUM LAGER BEER 1602 9.9 110 Local 14 5025 BS G ROYAL CHALLENGE PREMIUM LAGER BEER 1101 9.9 150 Local 15 5025 KK B ROYAL CHALLENGE PREMIUM LAGER BEER 4011 6.8 4840 Local 16 5025 UP G ROYAL CHALLENGE PREMIUM LAGER BEER 1402 9.9 100 Local 17 5028 AP C HAYWARDS 5000 SUPER STRONG BEER 2002 9.9 130 Local 18 5028 BS G HAYWARDS 5000 SUPER STRONG BEER 1201 9.9 160 Local 19 5028 UP G HAYWARDS 5000 SUPER STRONG BEER 1602 9.9 110 Local 20 5029 BS G KINGFISHER -

Development Laboratories for Alcoholic Beverages

Asahi Breweries, Ltd. Development Laboratories for Alcoholic Beverages Striving to create products that are sure to delight customers We are engaged in the development of new products across prod- uct lines including beer and related products (beer, happoshu [low-malt beer], new genre, etc.), ready-to-drink (RTD) alcoholic beverages (chuhai, cocktails, etc.), shochu, wine, and non-alcohol beverages (beer-taste and cocktail-taste beverages, etc.). From small-scale production of prototypes to follow-up for mass pro- duction at breweries and distilleries, we are always striving to create products that are sure to delight customers. Development of brewed alcoholic Development of RTD alcoholic Development of distilled beverages beverages alcoholic beverages When developing beer, wine and other For the development of canned chuhai and In the development of distilled alcoholic li- brewed alcoholic beverages, we produce cocktails, referred to as RTD alcoholic bev- quors such as shochu and spirits, a variety small batches of prototypes in a small-scale erages, we study techniques for preparing of factors and conditions need to be deter- plant to determine the flavor profile for the and blending ingredients such as fruit juice mined, from ingredient selection and pro- new product. Through this process, various and other flavoring agents to propose new cessing, yeast selection, as well as condi- factors and conditions will be determined flavors and meet the ever diversifying tions for wort preparation, fermentation, including the type and quantity of ingredi- tastes of consumers. We also explore and distillation, filtration, and maturation. New ents (malt, hop, grapes, etc.) to use, selec- evaluate new ingredients to create innova- product development entails the optimiza- tion of fermenting yeast, fermentation tem- tive flavors. -

Analytical Records Three Qualities

1265 130 is the conclusion of a story about a man who sold matter, 4’7 ° 58 per cent. The total nitrogen amounted to 4’00 an idea with money in it for a glass of beer. The astute per cent. Primox is a highly concentrated preparation and buyer of the idea, which was that of a zinc collar-pad should be useful as an emergency food. We attach little to prevent horses getting sore necks, argued "that the importance on dietetic grounds to the addition of vegetables matter oozing from the sores on the horses’ necks would in this preserved state. corrode the zinc pad and produce sulphate of zinc- LAUREL CAMPHOR SOAP (MILNE). thus the disease would provide its own remedy." It may be (THE GALEN MANUFACTURING Co., LIMITED. WiMON-STBEET, said that this was only the idea of the buyer, but the authors NEW CROSS-ROAD, LONDON, S.E.) of the book let it pass without a word of comment. Some This soap proved to be well made, containing a minimum salts of zinc would undoubtedly be produced, but surely not of moisture and giving absolutely no indication of alkaline the sulphate. However, as a whole the book puts the argu- excess. It is soft and agreeable to the skin and possesses an of ments for temperance in a forcible manner, but we do attractive odour. The soap is said to contain the oil think that in a book specially intended for schools such the camphor laurel, tar phenols and cymene. It yields a is suitable for errors as we have indicated should have no place. -

Crc - Liquor List

2701 W Howard Street Chicago, IL 60645-1303 PH: 773.465.3900 Fax: 773.465.6632 Rabbi Sholem Fishbane Kashruth Administrator Items listed as "Recommended" do not require a kosher symbol unless they are marked with a star (*) This list is updated regularly and should be considered accurate until December 31, 2013 cRc - Liquor List Bar Stock Items Bar Stock Items Bar equipment (strainers, shot measures, blenders, stir Other rods, shakers, etc.) used with non-kosher products Olives - Green should be properly cleaned and/or kashered prior to Require Certification use with kosher products. Onions - Pearl Canned or jarred require certification Recommended Coco Lopez OU* Beer Daily's OU* All unflavored beers with no additives are acceptable, OU* Holland House even without Kosher certification. This applies to both Jamaica John cRc* American and imported beers, light, dark and non- Jero OK* alcoholic beers. Mr & Mrs T OU or OK* Many breweries produce specialty brews that have Rose's - Grenadine OU* additives; please check the label and do not assume Rose's - Lime OU* that all varieties are acceptable. Furthermore, beers known to be produced at microbreweries, pub K* Tabasco - Hot Pepper Sauce breweries, or craft breweries require certification. Underberg - Herb Mix for Underberg OU* Natural Herb Bitters Recommended Other 800 - Ice Beer OU Bitters Anheuser-Busch - Redbridge Gluten Require Certification Free Coconut Milk Aspen Edge - Lager OU Requires Certification Blue Moon - Belgian White Ale OU* Cream of Coconut Blue Moon - Full Moon Winter Ale -

THE CHEMISTRY of BEER the Science in the Suds

THE CHEMISTRY OF BEER The Science in the Suds THE CHEMISTRY OF BEER The Science in the Suds ROGER BARTH, PHD Photography by Marcy Barth. Copyright © 2013 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. -

82 3460 Beer, Ale, Lager, Stout and Other Malt Liquor, Con Taining Not More Than 7% Alcohol by Weight Wholesale Distributors

82 OPINIONS 3460 BEER, ALE, LAGER, STOUT AND OTHER MALT LIQUOR, CON TAINING NOT MORE THAN 7% ALCOHOL BY WEIGHT WHOLESALE DISTRIBUTORS-B-1, B-2 PERMITS-EFFECT, AMENDMENT, JUNE 4, 1935, TO SECTION 6064-15 G.C.-PRO PORTIONAL REFUNDER PERMIT FEES-ADDITIONAL FEES - SECTION 6064-66 G.C., EFFECTIVE SEPTEMBER 5, 1935, SINCE REPEALED. SYLLABUS: Wholesale distributors of beer, ale, lager, stout and other malt liquors containing not more than seven per centum of alcohol by weight, who held B-2 permits under Section 6064-15, General Code, of the original Liquor Control Act (115 v. Pt. 2,118), were, upon the amendment of such sec tion in the act of June 4, 1935, which authorized the sale of malt. liquor of the above kinds by B-1 permit holders and the surrender and cancella tion of B-2 permits issued under the old law, with a proportional refunder of the permit fees paid therefor, required to pay the additional fees of "five cents per barrel for all beer and other malt liquor distributed and sold in Ohio in excess of five thousand barrels during the year covered by the permit," even though Section 6064-66, General Code ( since re pealed), authorizing surrender of the old B-2 permits, with consequent refunders, did not become effective until September 5, 1935. Columbus, Ohio, February 24, 1941. Honorable Jacob B. Taylor, Director, Department of Liquor Control, Columbus, Ohio. Dear Sir: I have your letter with enclosures with reference to the refund of certain liquor permit fees sought to be obtained by the Wholesale Beer ATTORNEY GENERAL 83 Association of Ohio, Inc. -

Beer Style Sheets ABV = Alcohol by Volume

Beer Style Sheets ABV = Alcohol by Volume Whynot Wheat (Wheat): American Style Wheat Non-Filtered Avg. ABV: 4.5-5.2% Our best selling beer. Characterized by a yellow color and cloudiness from the yeast remaining in suspension after fermentation. It has low hop bitterness, and a fruity aroma and flavor. Raider Red (Amber, Red): American Style Amber Ale Filtered Avg. ABV: 4.6-5.5% Our house amber. This amber ale is characterized by a copper to amber color and is very clear. Raider Red has a malt sweetness balanced by a hop bitterness. The aroma you will notice is hoppy. Black Cat Stout (Stout): Oatmeal Stout Non-Filtered Avg. ABV: 4.4-5.2% Our house dark beer. Like you would expect a stout to be; Black Cat Stout is black in color with a creamy head. Roasted barley and coffee notes are offset by slight hop bitterness. Medium bodied with a smooth finish. Big Bad Leroy Brown: American Brown Ale Filtered Avg. ABV: 5.2-5.8% Leroy Brown is brown in color with a nice maltiness offset by hop bitterness and hop flavor. American Pale Ale (APA): American Pale Ale Either Avg. ABV: 5.2-5.8% Our APA is golden in color and quite bitter with a high hop aroma. Very crisp and refreshing. Porter: Porter Non-Filtered Avg. ABV: 4.4-5.2% Our porter is black in color and medium in body. It has a roasted malt flavor and a dry finish with a taste of coffee. Give ‘Em Helles: Munich Style Helles Filtered Avg.