A Temperate and Wholesome Beverage: the Defense of the American Beer Industry, 1880-1920

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Real Life: Students' Quest

Uif!Kpvsobm!pg!Qbdjgjd!Vojpo!Dpmmfhf Winter 2007 REAL LIFE: STUDENTS’ QUEST viewpoint STAFF editorial viewpoint Executive Editor Julie Z. Lee, ’98 | [email protected] Editor Lainey S. Cronk, ’04 | [email protected] ASKING HARD QUESTIONS by Lainey S. Cronk | Alumni Editor Herb Ford, ’54 | [email protected] Sometimes people worry about me. I can see Layout and Design Barry Low, ’05 | [email protected] Art Director Cliff Rusch, ’80 | [email protected] something like a wince when I ask certain ques- Photo Editor Barry Low, ’05 | [email protected] tions. I can sense that under their intelligent de- Contributing Writers Christopher Togami, ‘07 Copy Editor Rita Hoshino, ’79 bate about possible answers they’re thinking, “Oh Cover Design Barry Low, ’05 dear, she must be struggling with her faith!” and PUC ADMINISTRATION “Where is this questioning going to take her?” President Richard Osborn, Ph.D. Vice President for Academic Administration Nancy Lecourt, Ph.D. Vice President for Financial Administration John Collins, ’70, Ed.D. Uif!zfbst!evsjoh!boe!kvtu!bgufs!dpmmfhf!xfsf!gvmm! jofwjubcmz!tqjmmfe!joup!fwfsz!bsfb!pg!nz!mjgf-! Vice President for Advancement Pam Sadler, CFRE Real Life pg!rvftujpot!gps!nf!jo!ufsnt!pg!sfmjhjpo/!Ipx!up! jodmvejoh!Hpe!boe!bmm!uijoht!tqjsjuvbm!boe! Vice President for Student Services Lisa Bissell Paulson, Ed.D. 4 Students’ Quest for Relevant Faith xpsl!uifn!pvu@!Ipx!up!bqqmz!uifn!jo!sfbmÒps!bu! sfmjhjpvtÒboe!uif!botxfst!pggfsfe!cz!nz!sfmjhjpo-! mfbtu!qptu.dpmmfhfÒmjgf!jo!b!xbz!uibu!J!dpvme!hsbtq! xijdi!xbt!gvodujpojoh!jo!tvdi!b!ejggfsfou!qmbof/ -

An Interpretation of the Captain Frederick Pabst Mansion: the Response Based Approach

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2000 An Interpretation of the Captain Frederick Pabst Mansion: The Response Based Approach Cheryl Elaine Brookshear University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Brookshear, Cheryl Elaine, "An Interpretation of the Captain Frederick Pabst Mansion: The Response Based Approach" (2000). Theses (Historic Preservation). 364. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/364 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Brookshear, Cheryl Elaine (2000). An Interpretation of the Captain Frederick Pabst Mansion: The Response Based Approach. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/364 For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Interpretation of the Captain Frederick Pabst Mansion: The Response Based Approach Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Brookshear, Cheryl Elaine (2000). An Interpretation of the Captain Frederick Pabst Mansion: The Response Based Approach. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/364 ^mm^'^^'^ M ilj- hmi mmtmm mini mm\ m m mm UNIVERSITVy PENNSYLV\NL\ LIBRARIES AN INTERPRETATION OF THE CAPTAIN FREDERICK PABST MANSION: THE RESPONSE BASED APPROACH Cheryl Elaine Brookshear A THESIS in Historic Preservation Presented to the Facuhies of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE 2000 V^u^^ Reader MossyPh. -

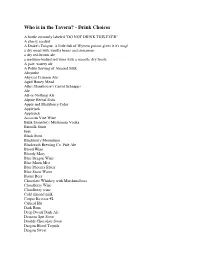

Drink Choices

Who is in the Tavern? - Drink Choices A bottle curiously labeled "DO NOT DRINK THIS EVER" A cherry cordial A Drake's Tongue. A little dab of Wyvern poison gives it it's zing! a dry mead with vanilla beans and cinnamon a dry red-brown ale a medium-bodied red wine with a smooth, dry finish A pale, watery ale A Polite Serving of Almond Milk Absynthe Abyssal Crimson Ale Aged Honey Mead Albis Shinehouse's Carrot Schnapps Ale All-or-Nothing Ale Alpine Herbal Soda Apple and Blackberry Cider Applejack Applejack Assassin Vine Wine Balik Stonefist's Mushroom Vodka Batmilk Stout beer Black Stout Blackberry Moonshine Blackwish Brewing Co. Pale Ale Blood Wine Bloody Mary Blue Dragon Wine Blue Moon Mist Blue Phoenix Elixir Blue Snow Water Butter Beer Chocolate Whiskey with Marshmallows Cloudberry Wine Cloudberry wine Cold almond milk Corpse Reviver #2 Critical Hit Dark Rum Deep Dwarf Dark Ale Demons Spit Stout Double Chocolate Stout Dragon Blood Tequila Dragon Sweat Dragon's Breath Ginger Beer Dragon's Breath Liquer Drambuie Dry red wine with sugared fruit slices. Dry white wine, aged in oak Dwarven Ale Dwarven Stout Elderblossom Wine Eleven Pear Cider from Imratheon Elorian Sprite Wine Elven Honey Mead Elven Pale Ale Elverquist (rare elven wine) Elvish Mint Tea Elvish Pale Ale Emerald Dream (absinthe) Fermented Owlbear Blood Firefly Ale -- For when you want to have a healthy glow about you. Firewine Five Foot's Frothingslosh Flametongue-Hellfire Pepper Porter fragrant mug of hot chamomile tea Ghost pepper pineapple juice Gimlet Ginger Scald Gnoll Booger -

Beer and Malt Handbook: Beer Types (PDF)

1. BEER TYPES The world is full of different beers, divided into a vast array of different types. Many classifications and precise definitions of beers having been formulated over the years, ours are not the most rigid, since we seek simply to review some of the most important beer types. In addition, we present a few options for the malt used for each type-hints for brewers considering different choices of malt when planning a new beer. The following beer types are given a short introduction to our Viking Malt malts. TOP FERMENTED BEERS: • Ales • Stouts and Porters • Wheat beers BOTTOM FERMENTED BEERS: • Lager • Dark lager • Pilsner • Bocks • Märzen 4 BEER & MALT HANDBOOK. BACKGROUND Known as the ‘mother’ of all pale lagers, pilsner originated in Bohemia, in the city of Pilsen. Pilsner is said to have been the first golden, clear lager beer, and is well known for its very soft brewing water, which PILSNER contributes to its smooth taste. Nowadays, for example, over half of the beer drunk in Germany is pilsner. DESCRIPTION Pilsner was originally famous for its fine hop aroma and strong bitterness. Its golden color and moderate alcohol content, and its slightly lower final attenuation, give it a smooth malty taste. Nowadays, the range of pilsner beers has extended in such a way that the less hopped and lighter versions are now considered ordinary lagers. TYPICAL ANALYSIS OF PILSNER Original gravity 11-12 °Plato Alcohol content 4.5-5.2 % volume C olor6 -12 °EBC Bitterness 2 5-40 BU COMMON MALT BASIS Pale Pilsner Malt is used according to the required specifications. -

BJCP Exam Study Guide

BJCP BEER EXAM STUDY GUIDE Last Revised: December, 2017 Contributing Authors: Original document by Edward Wolfe, Scott Bickham, David Houseman, Ginger Wotring, Dave Sapsis, Peter Garofalo, Chuck Hanning. Revised 2006 by Gordon Strong and Steve Piatz. Revised 2012 by Scott Bickham and Steve Piatz. Revised 2014 by Steve Piatz Revised 2015 by Steve Piatz Revised 2017 by Scott Bickham Copyright © 1998-2017 by the authors and the BJCP CHANGE LOG January-March, 2012: revised to reflect new exam structure, no longer interim May 1, 2012: revised yeast section, corrected T/F question 99 August, 2012: removed redundant styles for question S0, revised the additional readings list, updated the judging procedure to encompass the checkboxes on the score sheet. October 2012: reworded true/false questions 2, 4, 6, 8, 13, 26, 33, 38, 39, 42, and 118. Reworded essay question T15. March 2014: removed the Exam Program description from the document, clarified the wording on question T13. October 2015: revised for the 2015 BJCP Style Guidelines. February, 2016: revised the table for the S0 question to fix typos, removed untested styles. September-October, 2017 (Scott Bickham): moved the BJCP references in Section II.B. to Section I; incorporated a study guide for the online Entrance exam in Section II; amended the rubric for written questions S0, T1, T3, T13 and T15; rewrote the Water question and converted the rubrics for each of the Technical and Brewing Process questions to have three components; simplified the wording of the written exam questions’ added -

Jacob Riis: How the Other Half Lives

Name: ___(ANSWER KEY)___ Hour: ______ Jacob Riis: How the Other Half Lives Introduction The rapid growth of industrialization in the United States of the 1880s created an intense need for labor. The flood of tens of thousands of people— of them immigrants— northeastern cities created a housing problem of major proportions. Landlords, rushing to realize quick profits, persisted in subdividing their apartments into ever smaller units, forcing the poor into increasingly overcrowded living conditions. In the late 1880s, Jacob Riis, himself a Danish immigrant, began writing articles for the New York Sun that described the realities of life in New York City's slums. Riis was one of the first reporters to use flash photography, allowing him to take candid photos of living conditions among the urban poor. In 1890, he published How the Other Half Lives, illustrated with line drawings based on his photographs. Riis's work helped spark a new approach to reporting called "muckraking" that eventually led to the Progressive Era reform movements to improve these conditions. Here is an excerpt from Riis's book. How the Other Half Lives The twenty-five cent lodging-house keeps up the pretence of a bedroom, though the head-high partition enclosing a space just large enough to hold a cot and a chair and allow the man room to pull off his clothes is the shallowest of all pretences. The fifteen-cent bed stands boldly forth without screen in a room full of bunks with sheets as yellow and blankets as foul. At the ten-cent level the locker for the sleeper's clothes disappears. -

The Challenge of Slums: Socio-Economic Disparities

International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, Vol. 2, No. 5, September 2012 The Challenge of Slums: Socio-Economic Disparities Masoumeh Bagheri other important aspects such as informality [6]. The Abstract—The paper sheds light on the findings from a majority of these areas are developed in contradiction to survey carried out by the Informal Settlement Development building laws and planning regulations, as residents build Facility. This attempted, for the first time to identify houses on state-owned land or on privately-owned unplanned areas spatially in all the urban centres in Iran. agricultural land without getting permission to build or fit in Result of this study showed that, about 16 percent of the active with land use plans, it is considered illegal or informal populations in Ghale chenan are jobless or seeking a job, about 1933 of people are retired or physically disabled settlement and sometimes slums in Iran. As in other Third supported by different welfare organization. At present, one World countries, the dominant strategies for housing and of the important problems in Ahwaz is, its water service provision for [Iran‘s] urban poor include slum contamination, due to the flow of hospital, industrial, and upgrading and site and service schemes. However, the domestic sewage in the Karron River which supply drinking efficacy of these strategies has been limited by ambivalent water of residents. The very important point repeatedly government attitudes to irregular settlements [7] and to the occurring in the case of vulnerable, poor, and disadvantaged fact that ―in the eyes of the political elite, the administrator, strata especially the youth of Ghale chenan is illiteracy and unemployment. -

Rediscovering Milwaukee's Historic Breweries Part I: Milwaukee's Downtown Breweries Kevin M Cullen

Rediscovering Milwaukee's historic breweries Part I: Milwaukee's downtown breweries Kevin M Cullen When you mention Milwaukee, one asso- congregate in solidarity as we investigate ciation in particular comes to mind, beer. ancient and traditional alcoholic bever- This is because Milwaukee, Wisconsin ages around the world. Hence, it was a once boasted the largest production of logical and easy leap to get this eager beer than any other city in America and public on board to rediscover their own indeed the world. As an agricultural and city's brewing legacy. industrial hub on Lake Michigan for more than a century and a half with a thirsty Therefore, the first of what will be four population of ethnically proud beer ‘Legacies of Milwaukee Brewing’ tours lovers, Milwaukee was well poised to took place on 17 April 2010. It was decid- conquer the American brewing industry. ed given the breadth and scope of this What many people do not know however, city's brewing heritage, that we would is that this city has seen more than 100 focus our first tour on the historic and brewing companies come and go over contemporary breweries of downtown the past 170 years and unfortunately the Milwaukee. With Kalvin at the helm of a original breweries as well. full motor coach bus, Leonard Jurgensen as the Milwaukee brewery historian and I Therefore, as part of the Distant Mirror as the archaeological tour guide, we Archaeology Program at Discovery World made our way to one of Milwaukee's first (a science and technology museum in brewery sites at the end of Clybourn Milwaukee, Wisconsin) I am attempting Street (formerly Huron Street) and Lincoln to rediscover this brewing legacy through Memorial Drive (formerly the Lake urban archaeological expeditions. -

A.G. Perino Vermouth Classico

Introducing: A.G. Perino In celebration of our Italian Heritage, these vermouths are blended in honor the Perino Family's tradition of gathering to share great wine, great food, and great company. I have dedicated the brand to our grandfather, Anthony G. Peroni. We are committed to crafting high-quality vermouth that our discerning family would be proud to serve at their table. We are delighted to be able to share A.G. Perino Sweet and Dry Vermouth with you and your family. - Anthony G. Perino III OFFERINGS: Sweet Vermouth, Dry Vermouth SWEET VERMOUTH Sweet vermouth is a vermouth made from red wine with added essences of herbs, spices, and botanicals. TASTING NOTES Caramel in color, this vermouth leads with woodsy notes of balsam and clove and follow with warm flavors of walnut husk, vanilla, honey, and Ceylon cinnamon. Enjoy on the rocks with an orange peel garnish or mixed into a cocktail. RECIPES Cooking: Sweet vermouth can replace red wine in any recipe to add more flavor and depth to the dish. Chocolate sauce and jams are popular recipes using sweet vermouth Cocktails: Sweet vermouth can be sipped neat or on the rocks but is more commonly used in cocktails. Popular sweet vermouth cocktails include: Manhattan, Negroni, Rob Roy, Americano, and Vieux Carre. DRY VERMOUTH Dry vermouth is a vermouth made from white wine with added essences of herbs, spices, and botanicals. TASTING NOTES This vermouth leads with notes of citrus zest, followed by flavors of bay leaf, lemon grass, cucumber, lanolin, grapefruit pith, and white pepper. Enjoy on the rocks with a lemon twist or mixed into a cocktail. -

Adventists Doing?

The]ournal of the Association of Adventist Forums The Environment, Stupid , GOD AND THE COMPELLING '' CASE FOR NATURE RESURRECTION OF THE WORLD LETTERS FROM AFRICA WHAT ARE ADVENTISTS DOING? THE CURIOUS IMAGINATION APOCALYPTIC ANTI-IMPERIALISTS ACROBATIC ADVENTISTS January 1993 Volume 22, Number 5 Spectrum Editorial Board Consulting Editors I Beverly Beem Karen Bottomley Edna Maye Loveless Editor English History English I . Roy Branson Walla Walla College Canadian Union College La Sierra University Bonnie L Casey Edward Lugenbeal RoyBenlon if;:._, Anthropology Matbematical Sciences Writer/Editor i~\ Washington, D.C. Atlantic Union College Senior Editor Columbia Union College ~tl Donald R. McAdams TomDybdahl Roy Branson Raymond Cottrell President Etbics,l(ennedy Institute 1beology :1 Lorna Linda, California McAdanls, Faillace, aud Assoc. Georget<iwn University ! Clark Davis Mirgar~t McFarland Assistant Editor JOY ano Coleman c .... Asst Aftorney General Freelance Writer History University of Soutbem California Annapolis, Maryland Chip Cassano Berrien :>Jttings, Michigan Lawrence Geraty Ronald Numbers Molleurus Couperus History of Medicine ! Pbysician President Atlantic Union College University of Wisconsin News Editor · Angwin, California Fritz Guy Benjamin Reaves Gary Chartier Gene Daffern President Pbysician President Oakwood College Frederick, Maryland La Sierra University Karl Hall Gerhard Svrcek.Seiler I Book Review Editor Bonnie Dwyer History of Science Psychiatrist Journalism Beverly Beem Harvard University Vienna, Austria ·:! Folsom, -

September 2016 Historic Wauwatosa Published by the Wauwatosa Historical Society Inc

NO. 234 SEPTEMBER 2016 HISTORIC WAUWATOSA PUBLISHED BY THE WAUWATOSA HISTORICAL SOCIETY INC. KNEELAND-WALKER HOUSE WHS 2016 TOUR OF HOMES Washington Highlands 10 a.m. - 4 p.m. Saturday, Oct. 1 @ Advance tickets $14 WHS members* 100 $17 non-members Order online *For discount, members must call 414-774-8672 or order on line: WauwatosaHistoricalSociety.org Advance ticket locations (cash or check only) Wisconsin Garden and Pet 8520 W. North Ave. The Little Read Book 7603 W. State St. Tour-day ticket sales 6300 Washington Circle House descriptions begin on page 4 $17 WHS members $20 non-members When the Highlands housed mostly horses An excerpt from John Eastberg’s Pabst Farms, page 8 This painting by Theodore Breidweiser depicts Captain Pabst, his two sons, and the farm manager inspecting their stock. NOTEWORTHY WHS EMMER WAS A DREAM Linda and Jerry Stepaniak for VOLUNTEER, DOCENT overseeing popcorn sales; Phil The non-profit, Warner for maintaining the educational Wau- Any active WHS members in- watosa Historical grounds; Patty Fibich-Warner terested in local history probably for handling financial matters; Society (WHS) knew Dan Emmer even if they was founded to Kathy Causier for overseeing the research the his- didn’t know him by name. silent auction; Chris Vogel for tory of our area Emmer, who died July 28 at age hosting the artist reception; Steve and to collect, pre- 77, frequently portrayed historic Weber and Troop 21 Boy Scouts serve and exhibit figures at special events, most objects from our who helped take down tents and past. WHS is an recently as millionaire Emery put away tables and chairs plus affiliate of the Wis- Walker, one-time owner of the helping artists set up. -

A California Wine Primer

part one A California Wine Primer Olken_Ch00_FM.indd 1 7/13/10 12:07:51 PM Olken_Ch00_FM.indd 2 7/13/10 12:07:52 PM A Brief History of Wine in California more than two hundred years after Spanish missionaries brought vine cuttings with them from Mexico’s Baja California and established the first of the California missions in San Diego, researchers at Madrid’s National Biotechnical Center, using DNA techniques, have traced those first vines back to a black grape that seems to be a dark-colored relative of the Palomino grape still in use for the production of Sherry. That humble beginning may not seem like it would have much to do with today’s bur- geoning wine industry, but the fact is that the Mission variety became the vine of choice in California as its population grew first through the arrival of trappers and wealthy landowners, then with the small but steady stream of wagon trains that came west out of the country’s heartland and the establishment in the 1840s of the clipper ship trade. By the time the trans- continental railroad was completed in 1869, California’s wine economy had become established, and despite world wars and periods in which the sale of alcohol was banned, the industry hung on and finally exploded into its current shape with the wine boom of the 1970s. Today, the Mission grape is gone, but the wine industry it helped spawn now boasts over a half million acres of wine grapes from one end of the state to the other.