ON PLANT-BASED “MEAT” by Andy Amakihe1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Real Life: Students' Quest

Uif!Kpvsobm!pg!Qbdjgjd!Vojpo!Dpmmfhf Winter 2007 REAL LIFE: STUDENTS’ QUEST viewpoint STAFF editorial viewpoint Executive Editor Julie Z. Lee, ’98 | [email protected] Editor Lainey S. Cronk, ’04 | [email protected] ASKING HARD QUESTIONS by Lainey S. Cronk | Alumni Editor Herb Ford, ’54 | [email protected] Sometimes people worry about me. I can see Layout and Design Barry Low, ’05 | [email protected] Art Director Cliff Rusch, ’80 | [email protected] something like a wince when I ask certain ques- Photo Editor Barry Low, ’05 | [email protected] tions. I can sense that under their intelligent de- Contributing Writers Christopher Togami, ‘07 Copy Editor Rita Hoshino, ’79 bate about possible answers they’re thinking, “Oh Cover Design Barry Low, ’05 dear, she must be struggling with her faith!” and PUC ADMINISTRATION “Where is this questioning going to take her?” President Richard Osborn, Ph.D. Vice President for Academic Administration Nancy Lecourt, Ph.D. Vice President for Financial Administration John Collins, ’70, Ed.D. Uif!zfbst!evsjoh!boe!kvtu!bgufs!dpmmfhf!xfsf!gvmm! jofwjubcmz!tqjmmfe!joup!fwfsz!bsfb!pg!nz!mjgf-! Vice President for Advancement Pam Sadler, CFRE Real Life pg!rvftujpot!gps!nf!jo!ufsnt!pg!sfmjhjpo/!Ipx!up! jodmvejoh!Hpe!boe!bmm!uijoht!tqjsjuvbm!boe! Vice President for Student Services Lisa Bissell Paulson, Ed.D. 4 Students’ Quest for Relevant Faith xpsl!uifn!pvu@!Ipx!up!bqqmz!uifn!jo!sfbmÒps!bu! sfmjhjpvtÒboe!uif!botxfst!pggfsfe!cz!nz!sfmjhjpo-! mfbtu!qptu.dpmmfhfÒmjgf!jo!b!xbz!uibu!J!dpvme!hsbtq! xijdi!xbt!gvodujpojoh!jo!tvdi!b!ejggfsfou!qmbof/ -

A Temperate and Wholesome Beverage: the Defense of the American Beer Industry, 1880-1920

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 7-3-2018 A Temperate and Wholesome Beverage: the Defense of the American Beer Industry, 1880-1920 Lyndsay Danielle Smith Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smith, Lyndsay Danielle, "A Temperate and Wholesome Beverage: the Defense of the American Beer Industry, 1880-1920" (2018). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4497. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6381 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. A Temperate and Wholesome Beverage: The Defense of the American Beer Industry, 1880-1920 by Lyndsay Danielle Smith A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: Catherine McNeur, Chair Katrine Barber Joseph Bohling Nathan McClintock Portland State University 2018 © 2018 Lyndsay Danielle Smith i Abstract For decades prior to National Prohibition, the “liquor question” received attention from various temperance, prohibition, and liquor interest groups. Between 1880 and 1920, these groups gained public interest in their own way. The liquor interests defended their industries against politicians, religious leaders, and social reformers, but ultimately failed. While current historical scholarship links the different liquor industries together, the beer industry constantly worked to distinguish itself from other alcoholic beverages. -

Adventists Doing?

The]ournal of the Association of Adventist Forums The Environment, Stupid , GOD AND THE COMPELLING '' CASE FOR NATURE RESURRECTION OF THE WORLD LETTERS FROM AFRICA WHAT ARE ADVENTISTS DOING? THE CURIOUS IMAGINATION APOCALYPTIC ANTI-IMPERIALISTS ACROBATIC ADVENTISTS January 1993 Volume 22, Number 5 Spectrum Editorial Board Consulting Editors I Beverly Beem Karen Bottomley Edna Maye Loveless Editor English History English I . Roy Branson Walla Walla College Canadian Union College La Sierra University Bonnie L Casey Edward Lugenbeal RoyBenlon if;:._, Anthropology Matbematical Sciences Writer/Editor i~\ Washington, D.C. Atlantic Union College Senior Editor Columbia Union College ~tl Donald R. McAdams TomDybdahl Roy Branson Raymond Cottrell President Etbics,l(ennedy Institute 1beology :1 Lorna Linda, California McAdanls, Faillace, aud Assoc. Georget<iwn University ! Clark Davis Mirgar~t McFarland Assistant Editor JOY ano Coleman c .... Asst Aftorney General Freelance Writer History University of Soutbem California Annapolis, Maryland Chip Cassano Berrien :>Jttings, Michigan Lawrence Geraty Ronald Numbers Molleurus Couperus History of Medicine ! Pbysician President Atlantic Union College University of Wisconsin News Editor · Angwin, California Fritz Guy Benjamin Reaves Gary Chartier Gene Daffern President Pbysician President Oakwood College Frederick, Maryland La Sierra University Karl Hall Gerhard Svrcek.Seiler I Book Review Editor Bonnie Dwyer History of Science Psychiatrist Journalism Beverly Beem Harvard University Vienna, Austria ·:! Folsom, -

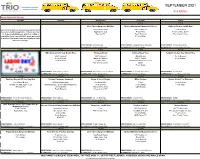

September 2021 K-8 Menu

LANCER CATERING 651-646-2197 X32 SEPTEMBER 2021 K-8 MENU Menu Subject to Change Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday 1-Sep 2-Sep 3-Sep Beef Cheeseburger on WG Bun Chicken Marinara w/ Mozzarella Cheese Buffalo Chicken on WG Bun Lancer Dining Services does not use peanuts, pork, Veg Baked Beans WG Teabiscuit Fresh Carrots tree nut or shellfish ingredients. All items are baked Applesauce Cup Brown Rice Fresh Celery Sticks or steamed, mindfully made with fresh or frozen Ketchup PC Fresh Broccoli Fruit Chef's Choice vegetables (never canned!),100% whole grains and Fresh Orange a variety of lean meats using heart-healthy oils and low-salt seasonings. 0 VEGETARIAN: Gardenburger VEGETARIAN: Cheesebread w/ Marinara VEGETARIAN: Cheese Quesadilla ALTERNATE: Chicken Buffalo Wrap ALTERNATE: SW Chicken Wrap ALTERNATE: Pizza or Turkey Club Sub 6-Sep 7-Sep 8-Sep 9-Sep 10-Sep BBQ Drumstick w/ Veg. Brown Rice Turkey w/Gravy Softshell Beef Taco Teriyaki Chicken Over Brown Rice WG Teabiscuit WG Teabiscuit Black Beans Fresh Broccoli Fresh Carrots Mashed Potatoes WG 8" Tortilla Fresh Orange Fresh Banana Fresh Celery Shredded Cheese & Lettuce Fruit Chef's Choice Salsa Fresh Apple 0 0 CLOSED VEGETARIAN: Tofu w/ Sweet & Sour VEGETARIAN: Gardenburger w/ Veg Gravy VEGETARIAN: Vegetarian Taco Meat VEGETARIAN: Teriyaki Tofu ALTERNATE: Chicken Cheddar Wrap ALTERNATE: Chicken Buffalo Wrap ALTERNATE: SW Chicken Wrap ALTERNATE: Pizza or Turkey Club Sub 13-Sep 14-Sep 15-Sep 16-Sep 17-Sep Beef Hot Dog on WG Hot Dog Bun Chicken Parmesan Sandwich Sweet & Sour Chicken BBQ Chicken Bosco Sticks 6" w/ Marinara Veg. -

Mckee Minute January/February 2015

Southern Adventist University KnowledgeExchange@Southern McKee Minute – McKee Library This Month Library Publications 1-2015 McKee Minute January/February 2015 McKee Library Follow this and additional works at: https://knowledge.e.southern.edu/m_minute Recommended Citation McKee Library, "McKee Minute January/February 2015" (2015). McKee Minute – McKee Library This Month. 23. https://knowledge.e.southern.edu/m_minute/23 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Library Publications at KnowledgeExchange@Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in McKee Minute – McKee Library This Month by an authorized administrator of KnowledgeExchange@Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. McKeeMcKee Library Faculty & Staff Newsletter Minute January/February 2015 THERAPY DOGS AT THE LIBRARY Local therapy dogs visited with students before finals last semester On Friday, December 12, 2014, International for the library’s visit in the near future. therapy dogs again in May. McKee Library proudly hosted first ever therapy dog visit. The use of therapy five dogs from Therapy Dog Many students came to the dogs in academic library to visit with the libraries is not a new dogs, with several students concept. Many libraries coming more than one offer students a chance time. Even a few faculty to socialize with these members joined in on the dogs in order to reduce fun. stress, especially during The event was an finals. overwhelming success, with The library is students requesting a return planning to host the Library News In this Edition Valentine’s Day events, library instruction, and vault display Health & Well-being 2 Valentine’s Events event gives students a chance to about the embedded librarian McKee Library is proud to select a book to read based on a service? Contact Katie McGrath Christianity & History 2 offer two Valentine’s Day events few characteristics of the work. -

Y Ou R Ca Fe Te Ri A

VeganizeVeganize YOURYOUR CAFETERIA CAFETERIA © Steve Lee Studios Dear Student, Thanks for your interest in getting more vegan options offered in your cafeteria. With the addition of plant-based entrées, you can spare thousands of animals a life of misery. As more high school students stop eating animals, cafeteria managers are working to accommodate students’ dietary choices. So what kind of legacy do you want to leave at your school? By dedicating a few hours to meetings, you can help create monumental changes for animals and expose students to vegan options that they otherwise would never have had the opportunity to try. PETA is here to provide support and guidance throughout the process. In this guide, we’ve laid out the steps necessary for your school to earn an “A” on the PETA Vegan Report Card. Feel free to contact our team, which helps students increase the number of vegan options at their schools. E-mail us at [email protected]. Students across the country are working with PETA and winning victories for animals. The more praise and demand for plant-based foods that cafeterias receive, the greater the number of vegan dining options they will offer. So let’s get started! Sincerely, PETA Alptraum | Chick: © Dreamstime.com THE Five-StepPROCESS FOR MORE VEGAN OPTIONS STEP 1: INVESTIGATIVE PROCESS Survey the Options Already Available Find out which vegan options already exist and how often they’re served—the more thorough your assessment, the more prepared and knowledgeable you’ll be when you meet with the cafeteria manager. Know who your school’s food-service provider is. -

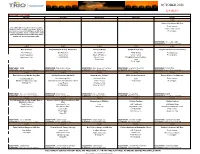

October 2021

LANCER CATERING 651-646-2197 X32 OCTOBER 2021 K-8 MENU Menu Subject to Change Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday 1-Oct Buffalo Chicken on WG Bun Fresh Carrots Lancer Dining Services does not use peanuts, pork, tree nut or shellfish ingredients. All items Fresh Celery Sticks are baked or steamed, mindfully made with fresh Fresh Apple or frozen vegetables (never canned!),100% whole grains and a variety of lean meats using heart- healthy oils and low-salt seasonings. VEGETARIAN: Cheese Quesadilla ALTERNATE: Pizza or Turkey Club Sub 4-Oct 5-Oct 6-Oct 7-Oct 8-Oct Mac & Cheese BBQ Drumstick w/ Veg. Brown Rice Turkey w/Gravy Softshell Beef Taco Teriyaki Chicken Over Brown Rice WG Teabiscuit WG Teabiscuit WG Teabiscuit Black Beans Fresh Broccoli Mixed Vegetables Fresh Carrots Mashed Potatoes WG 8" Tortilla Fresh Orange Applesauce Cup Fresh Banana Fresh Celery Shredded Cheese & Lettuce Peach Cup Salsa Fresh Apple 0 0 0 VEGETARIAN: NONE VEGETARIAN: Tofu w/ Sweet & Sour VEGETARIAN: Gardenburger w/ Veg Gravy VEGETARIAN: Vegetarian Taco Meat VEGETARIAN: Teriyaki Tofu ALTERNATE: Roast Turkey & Cheese Sandwich ALTERNATE: Chicken Cheddar Wrap ALTERNATE: Chicken Buffalo Wrap ALTERNATE: SW Chicken Wrap ALTERNATE: Pizza or Turkey Club Sub 11-Oct 12-Oct 13-Oct 14-Oct 15-Oct Beef Hot Dog on WG Hot Dog Bun Chicken Parmesan Sandwich Sweet & Sour Chicken BBQ Chicken Sandwich Bosco Sticks 6" w/ Marinara Veg. Baked Beans WG Hamburger Bun Veg Brown Rice Corn Fresh Carrots Strawberry Applesauce Cup Marinara Sauce & Shredded Mozzarella Fresh Broccoli Fresh Orange -

Vegetarian Starter Kit You from a Family Every Time Hold in Your Hands Today

inside: Vegetarian recipes tips Starter info Kit everything you need to know to adopt a healthy and compassionate diet the of how story i became vegetarian Chinese, Indian, Thai, and Middle Eastern dishes were vegetarian. I now know that being a vegetarian is as simple as choosing your dinner from a different section of the menu and shopping in a different aisle of the MFA’s Executive Director Nathan Runkle. grocery store. Though the animals were my initial reason for Dear Friend, eliminating meat, dairy and eggs from my diet, the health benefi ts of my I became a vegetarian when I was 11 years old, after choice were soon picking up and taking to heart the content of a piece apparent. Coming of literature very similar to this Vegetarian Starter Kit you from a family every time hold in your hands today. plagued with cancer we eat we Growing up on a small farm off the back country and heart disease, roads of Saint Paris, Ohio, I was surrounded by which drastically cut are making animals since the day I was born. Like most children, short the lives of I grew up with a natural affi nity for animals, and over both my mother and time I developed strong bonds and friendships with grandfather, I was a powerful our family’s dogs and cats with whom we shared our all too familiar with home. the effect diet can choice have on one’s health. However, it wasn’t until later in life that I made the connection between my beloved dog, Sadie, for whom The fruits, vegetables, beans, and whole grains my diet I would do anything to protect her from abuse and now revolved around made me feel healthier and gave discomfort, and the nameless pigs, cows, and chickens me more energy than ever before. -

World Nutrition Volume 5, Number 3, March 2014

World Nutrition Volume 5, Number 3, March 2014 World Nutrition Volume 5, Number 3, March 2014 Journal of the World Public Health Nutrition Association Published monthly at www.wphna.org Processing. Breakfast food Amazing tales of ready-to-eat breakfast cereals Melanie Warner Boulder, Colorado, US Emails: [email protected] Introduction There are products we all know or should know are bad for us, such as chips (crisps), sodas (soft drinks), hot dogs, cookies (biscuits), and a lot of fast food. Nobody has ever put these items on a healthy list, except perhaps industry people. Loaded up with sugar, salt and white flour, they offer about as much nutritional value as the packages they’re sold in. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg, the obvious stuff. The reach of the processed food industry goes a lot deeper than we think, extending to products designed to look as if they’re not really processed at all. Take, for instance, chains that sell what many people hope and believe are ‘fresh’ sandwiches. But since when does fresh food have a brew of preservatives like sodium benzoate and calcium disodium EDTA, meat fillers like soy protein, and manufactured flavourings like yeast extract and hydrolysed vegetable protein? Counting up the large number of ingredients in just one sandwich can make you cross-eyed. I first became aware of the enormity of the complex field known as food science back in 2006 when I attended an industry trade show. That year IFT, which is for the Institute of Food Technologists, and is one of the food industry’s biggest gatherings, was held in New Warner M. -

Eternity Marius Munteanu by Lisa M

THE JOURNAL OF ADVENTISTWebsite: http://jae.adventist.org EDUCATION April-June 2017 E DUCATINGD U C A T I N G FORF O R E TERNITY TheThe GreatGreat TheThe DivineDivine CognitiveCognitive andand IIncreasingncreasing SStrengtheningtrengthening CCommissionommission BBlueprintlueprint fforor NNon-cognitiveon-cognitive SStudenttudent AAccessccess AAdventistdventist and the Education Factors in K-12 Education Education in Educational Contributing the North Imperative to Academic American Division Success SPECIALSee page 37 ISSUE The Journal of CONTENTS ADVENTIST EDUCATION EDITOR Faith-Ann McGarrell EDITOR EMERITUS Beverly J. Robinson-Rumble ASSOCIATE EDITOR S PECIAL I SSUE (INTERNATIONAL EDITION) Julián Melgosa SENIOR CONSULTANTS John Wesley Taylor V Lisa M. Beardsley-Hardy Geoffrey G. Mwbana, Ella Smith Simmons CONSULTANTS APRIL-JUNE 2017 • VOLUME 79, NO. 3 GENERAL CONFERENCE John M. Fowler, Mike Mile Lekic, Hudson E. Kibuuka EAST-CENTRAL AFRICA Andrew Mutero EURO-AFRICA 3 Editorial: Educating for Eternity Marius Munteanu By Lisa M. Beardsley-Hardy EURO-ASIA Vladimir Tkachuk INTER-AMERICA 4 The Great Commission and the Educational Imperative Gamaliel Florez By George R. Knight MIDDLE EAST-NORTH AFRICA Leif Hongisto NORTH AMERICA 11 The State of Adventist Education Report Larry Blackmer By Lisa M. Beardsley-Hardy NORTHERN ASIA-PACIFIC Richard A. Saubin SOUTH AMERICA 16 CognitiveGenesis: Cognitive and Non-cognitive Factors Edgard Luz Contributing to Academic Success in Adventist Education SOUTH PACIFIC By Elissa Kido Carol Tasker SOUTHERN AFRICA-INDIAN OCEAN EllMozecie Kadyakapitando 20 The Divine Blueprint for Education—A Devotional SOUTHERN ASIA By George W. Reid Prabhu Das R N SOUTHERN ASIA-PACIFIC 22 Increasing Student Access in K to 12 Education: A Challenge Lawrence L. -

The Western Health Reform Institute

Avondale College ResearchOnline@Avondale Science and Mathematics Book Chapters School of Science and Mathematics 11-2015 The Western Health Reform Institute Paul U. Cameron Monash University, [email protected] Lynden Rogers Avondale College of Higher Education, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://research.avondale.edu.au/sci_math_chapters Part of the Other Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Cameron, P. U., & Rogers, L. J. (2015). The western health reform institute. In L. Rogers (Ed.), Changing attitudes to science within Adventist health and medicine from 1865 to 2015 (pp. 1-13). Cooranbong, Australia: Avondale Academic Press. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Science and Mathematics at ResearchOnline@Avondale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Science and Mathematics Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@Avondale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter 1 The Western Health Reform Institute Paul U. Cameron and Lynden J. Rogers Introduction The grand opening of the Western Health Reform Institute (WHRI) in Battle Creek, Michigan, on September 5, 1866, was a gala occasion. It was only a short time after Ellen White had focussed attention on the need for such an institution during her stirring address to the 1866 General Conference Session. Despite having limited means, some $11,000 had been raised by gift or subscription loan during a fundraising campaign spearheaded by Elders John N. Loughborough in the West and John N. Andrews in the East. On September 11 the editor of the Review and Herald, Uriah Smith, reported on the successful opening, noting that, “it was less than four short months ago, for the time when this matter first began to take practical shape among our people.”1 J. -

Vegan Cooking for Carnivores Let Me Start Off by Saying That I Am Not a Chef, and I Have Never Been to Cooking School

Vegan Cooking For Carnivores Let me start off by saying that I am not a chef, and I have never been to cooking school. I learned to cook by watching my parents cook dinner every night and soon developed a love for cooking and especially baking. When I became vegan 12 years ago, I did so because of my love for animals and I realized that I didn’t need to consume animal products to live a healthy life. I didn’t do it because I didn’t like the taste of meat. If someone were to come out with a vegan steak that actually tasted like steak, I would be first in line to buy it. Anyway my point is that becoming vegan didn’t mean that I wanted to live off beans and sprouts for the rest of my life. I started off by modifying recipes I had always used and then as I got more adventurous, and as more meat and dairy alternatives came on the market, I started coming up with new recipes. None of my friends and family are vegan, it’s just me and my husband, so when I have people over for dinner, I like to make sure that they come back. That means making meals that taste like food they are used to. I’ve had several occasions where people have come over for dinner and doubted the food was vegan. The introduction food I make is so much like the real thing that my guests actually think I’ve strayed and put meat or dairy in it.