Trouble Brewing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North America CANADA

North America CANADA Gallons Guzzled 17.49 Gal Per Person Per Year Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site Alberta Calgary Big Rock Brewery McNally's Ale Dec-01 15.5 5.0% Gary B. www.bigrockbeer.com Cold Cock Winter Porter May-09 17.0 Gary B. Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site British Columbia Pacific Western Brewing Prince George Bulldog Canadian Lager May-09 16.0 Helen B. Company Vancouver Molson Breweries Molson Canadian Lager May-05 17.0 5.0% Helen B. Vancouver Island Brewing Vancouver Piper's Pale Ale May-09 16.0 Helen B. Company Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site Manitoba Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site New Brunswick Saint John Moosehead Brewery Moosehead Lager Jul-01 17.0 5.1% Gary B. Moosehead Light Lager Sep-09 15.0 4.8% Maurice S. Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site New Foundland St. John's Labatt Brewing Company Budweiser Lager Sep-02 18.0 5.0% Gary B. Bud Light Lager Sep-02 16.0 4.0% Gary B. St. John's Molson Brewery L.T.D. Black Horse Lager Sep-02 18.5 5.0% Gary B. Molson Canadian Lager Sep-09 17.5 5.0% Maurice S. Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site Northwest Territories Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site Nova Scotia Halifax Labatt Brewing Company Labatt's Blue Pilsner Set-02 16.0 4.3% Maurice S. -

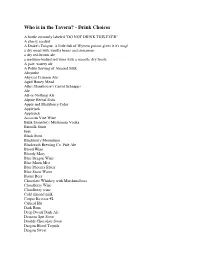

Drink Choices

Who is in the Tavern? - Drink Choices A bottle curiously labeled "DO NOT DRINK THIS EVER" A cherry cordial A Drake's Tongue. A little dab of Wyvern poison gives it it's zing! a dry mead with vanilla beans and cinnamon a dry red-brown ale a medium-bodied red wine with a smooth, dry finish A pale, watery ale A Polite Serving of Almond Milk Absynthe Abyssal Crimson Ale Aged Honey Mead Albis Shinehouse's Carrot Schnapps Ale All-or-Nothing Ale Alpine Herbal Soda Apple and Blackberry Cider Applejack Applejack Assassin Vine Wine Balik Stonefist's Mushroom Vodka Batmilk Stout beer Black Stout Blackberry Moonshine Blackwish Brewing Co. Pale Ale Blood Wine Bloody Mary Blue Dragon Wine Blue Moon Mist Blue Phoenix Elixir Blue Snow Water Butter Beer Chocolate Whiskey with Marshmallows Cloudberry Wine Cloudberry wine Cold almond milk Corpse Reviver #2 Critical Hit Dark Rum Deep Dwarf Dark Ale Demons Spit Stout Double Chocolate Stout Dragon Blood Tequila Dragon Sweat Dragon's Breath Ginger Beer Dragon's Breath Liquer Drambuie Dry red wine with sugared fruit slices. Dry white wine, aged in oak Dwarven Ale Dwarven Stout Elderblossom Wine Eleven Pear Cider from Imratheon Elorian Sprite Wine Elven Honey Mead Elven Pale Ale Elverquist (rare elven wine) Elvish Mint Tea Elvish Pale Ale Emerald Dream (absinthe) Fermented Owlbear Blood Firefly Ale -- For when you want to have a healthy glow about you. Firewine Five Foot's Frothingslosh Flametongue-Hellfire Pepper Porter fragrant mug of hot chamomile tea Ghost pepper pineapple juice Gimlet Ginger Scald Gnoll Booger -

A Temperate and Wholesome Beverage: the Defense of the American Beer Industry, 1880-1920

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 7-3-2018 A Temperate and Wholesome Beverage: the Defense of the American Beer Industry, 1880-1920 Lyndsay Danielle Smith Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smith, Lyndsay Danielle, "A Temperate and Wholesome Beverage: the Defense of the American Beer Industry, 1880-1920" (2018). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4497. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6381 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. A Temperate and Wholesome Beverage: The Defense of the American Beer Industry, 1880-1920 by Lyndsay Danielle Smith A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: Catherine McNeur, Chair Katrine Barber Joseph Bohling Nathan McClintock Portland State University 2018 © 2018 Lyndsay Danielle Smith i Abstract For decades prior to National Prohibition, the “liquor question” received attention from various temperance, prohibition, and liquor interest groups. Between 1880 and 1920, these groups gained public interest in their own way. The liquor interests defended their industries against politicians, religious leaders, and social reformers, but ultimately failed. While current historical scholarship links the different liquor industries together, the beer industry constantly worked to distinguish itself from other alcoholic beverages. -

The Golden Moments of Paris: a Guide to the Paris of the 1920S Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE GOLDEN MOMENTS OF PARIS: A GUIDE TO THE PARIS OF THE 1920S PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Baxter | 272 pages | 04 Apr 2014 | Museyon Guides | 9780984633470 | English | New York, United States The Golden Moments of Paris: A Guide to the Paris of the 1920s PDF Book Gil has a great passion for the past throughout the movie but by the end of the story he realizes that we must live in the present and that the proper use of the past is to take the lessons that it provides and use them to help us live well. Williams New York Patrick T. A constantly evolving mix of cafes, small stores, art galleries, and residential units predominate. Further information: Cars in the s. The city is home to 10 three-starred Michelin restaurants, with a further 67 achieving at least one star. Essential We use cookies to provide our services , for example, to keep track of items stored in your shopping basket, prevent fraudulent activity, improve the security of our services, keep track of your specific preferences e. As to theme, Gil eventually realizes that he has no choice but to be in the present and that he must embrace the future, using inspiration and lessons from the past as they apply. His popular novel Main Street satirized the dull and ignorant lives of the residents of a Midwestern town. Vienna psychiatrist Sigmund Freud — played a major role in Psychoanalysis , which impacted avant-garde thinking, especially in the humanities and artistic fields. Forstall System — Independent U. Alcohol prohibition. Taylor Pleasantly surprised with how much I liked this book. -

The Pioneering Efforts of Wise Women in Medicine and The

THE PIONEERING EFFORTS OF WISE WOMEN IN MEDICINE AND THE MEDICAL SCIENCES EDITORS Gerald Friedland MD, FRCPE, FRCR Jennifer Tender, MD Leah Dickstein, MD Linda Shortliffe, MD 1 PREFACE A boy and his father are in a terrible car crash. The father is killed and the child suffers head trauma and is taken to the local emergency room for a neurosurgical procedure. The attending neurosurgeon walks into the emergency room and states “I cannot perform the surgery. This is my son.” Who is the neurosurgeon? Forty years ago, this riddle stumped elementary school students, but now children are perplexed by its simplicity and quickly respond “the doctor is his mother.” Although this new generation may not make presumptions about the gender of a physician or consider a woman neurosurgeon to be an anomaly, medicine still needs to undergo major changes before it can be truly egalitarian. When Dr. Gerald Friedland’s wife and daughter became physicians, he became more sensitive to the discrimination faced by women in medicine. He approached Linda Shortliffe, MD (Professor of Urology, Stanford University School of Medicine) and asked whether she would be willing to hold the first reported conference to highlight Women in Medicine and the Sciences. She agreed. The conference was held in the Fairchild Auditorium at the Stanford University School of Medicine on March 10, 2000. In 2012 Leah Dickstein, MD contacted Gerald Friedland and informed him that she had a video of the conference. This video was transformed into the back-bone of this book. The chapters have been edited and updated and the lectures translated into written prose. -

Beer and Malt Handbook: Beer Types (PDF)

1. BEER TYPES The world is full of different beers, divided into a vast array of different types. Many classifications and precise definitions of beers having been formulated over the years, ours are not the most rigid, since we seek simply to review some of the most important beer types. In addition, we present a few options for the malt used for each type-hints for brewers considering different choices of malt when planning a new beer. The following beer types are given a short introduction to our Viking Malt malts. TOP FERMENTED BEERS: • Ales • Stouts and Porters • Wheat beers BOTTOM FERMENTED BEERS: • Lager • Dark lager • Pilsner • Bocks • Märzen 4 BEER & MALT HANDBOOK. BACKGROUND Known as the ‘mother’ of all pale lagers, pilsner originated in Bohemia, in the city of Pilsen. Pilsner is said to have been the first golden, clear lager beer, and is well known for its very soft brewing water, which PILSNER contributes to its smooth taste. Nowadays, for example, over half of the beer drunk in Germany is pilsner. DESCRIPTION Pilsner was originally famous for its fine hop aroma and strong bitterness. Its golden color and moderate alcohol content, and its slightly lower final attenuation, give it a smooth malty taste. Nowadays, the range of pilsner beers has extended in such a way that the less hopped and lighter versions are now considered ordinary lagers. TYPICAL ANALYSIS OF PILSNER Original gravity 11-12 °Plato Alcohol content 4.5-5.2 % volume C olor6 -12 °EBC Bitterness 2 5-40 BU COMMON MALT BASIS Pale Pilsner Malt is used according to the required specifications. -

Development Laboratories for Alcoholic Beverages

Asahi Breweries, Ltd. Development Laboratories for Alcoholic Beverages Striving to create products that are sure to delight customers We are engaged in the development of new products across prod- uct lines including beer and related products (beer, happoshu [low-malt beer], new genre, etc.), ready-to-drink (RTD) alcoholic beverages (chuhai, cocktails, etc.), shochu, wine, and non-alcohol beverages (beer-taste and cocktail-taste beverages, etc.). From small-scale production of prototypes to follow-up for mass pro- duction at breweries and distilleries, we are always striving to create products that are sure to delight customers. Development of brewed alcoholic Development of RTD alcoholic Development of distilled beverages beverages alcoholic beverages When developing beer, wine and other For the development of canned chuhai and In the development of distilled alcoholic li- brewed alcoholic beverages, we produce cocktails, referred to as RTD alcoholic bev- quors such as shochu and spirits, a variety small batches of prototypes in a small-scale erages, we study techniques for preparing of factors and conditions need to be deter- plant to determine the flavor profile for the and blending ingredients such as fruit juice mined, from ingredient selection and pro- new product. Through this process, various and other flavoring agents to propose new cessing, yeast selection, as well as condi- factors and conditions will be determined flavors and meet the ever diversifying tions for wort preparation, fermentation, including the type and quantity of ingredi- tastes of consumers. We also explore and distillation, filtration, and maturation. New ents (malt, hop, grapes, etc.) to use, selec- evaluate new ingredients to create innova- product development entails the optimiza- tion of fermenting yeast, fermentation tem- tive flavors. -

Analytical Records Three Qualities

1265 130 is the conclusion of a story about a man who sold matter, 4’7 ° 58 per cent. The total nitrogen amounted to 4’00 an idea with money in it for a glass of beer. The astute per cent. Primox is a highly concentrated preparation and buyer of the idea, which was that of a zinc collar-pad should be useful as an emergency food. We attach little to prevent horses getting sore necks, argued "that the importance on dietetic grounds to the addition of vegetables matter oozing from the sores on the horses’ necks would in this preserved state. corrode the zinc pad and produce sulphate of zinc- LAUREL CAMPHOR SOAP (MILNE). thus the disease would provide its own remedy." It may be (THE GALEN MANUFACTURING Co., LIMITED. WiMON-STBEET, said that this was only the idea of the buyer, but the authors NEW CROSS-ROAD, LONDON, S.E.) of the book let it pass without a word of comment. Some This soap proved to be well made, containing a minimum salts of zinc would undoubtedly be produced, but surely not of moisture and giving absolutely no indication of alkaline the sulphate. However, as a whole the book puts the argu- excess. It is soft and agreeable to the skin and possesses an of ments for temperance in a forcible manner, but we do attractive odour. The soap is said to contain the oil think that in a book specially intended for schools such the camphor laurel, tar phenols and cymene. It yields a is suitable for errors as we have indicated should have no place. -

Chicago Jewish History

Look to the rock from which you were hewn Vol. 30, No. 3, Summer 2006 chicago jewish historical society chicago jewish history Sunday, September 17—Save the Date! Thrilling Chapters from Chicago’s Jewish Past: “Meyer Levin’s Compulsion Trial and Ben Hecht’s Zionist Pageants” The next open meeting of the Chicago Jewish Historical Society will feature a talk by our president, Walter Roth, marking the publication of the paperback edition of his book, Looking Backward— True Stories from Chicago’s Jewish Past. The meeting will be held on Sunday afternoon, September 17, in the chapel of Temple Sholom, 3480 North Lake Shore Drive, Chicago. The program will begin at 2:00 p.m. following a social hour with refreshments at 1:00 p.m. and a brief annual meeting with election of members to the Board of Directors. A book-signing will follow the program. Mr. Roth will speak on two fascinating chapters of his book: one concerns author Meyer Levin’s courtroom battle with Nathan Leopold over the publication of Compulsion, Levin’s fictionalized account of the Loeb and Leopold “crime of the century;” the other tells of screenwriter Ben Hecht’s transformation into an ardent Zionist and his subsequent authorship of two provocative pageants—We Will Never Die and A Flag is Born. Admission is free and open to the public. The Temple Sholom parking lot is south of the temple, on Stratford Street, facing the temple entrance. For information call the Society office at (312) 663-5634. O Sunday, October 29—Save the Date! Chicago Architecture Foundation & Chicago Jewish Historical Society Program: IN THIS ISSUE “Remembering North Lawndale” Dr. -

TTB Ruling 2008-3

DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY TTB Ruling Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau TTB Ruling Number: 2008–3 July 7, 2008 Classification of Brewed Products as “Beer” Under the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 and as “Malt Beverages” Under the Federal Alcohol Administration Act The Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau issues this ruling to clarify that certain brewed products that are classified as “beer” under the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 do not meet the definition of a “malt beverage” under the Federal Alcohol Administration Act. TTB Ruling 2008–3 Background In recent months, the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) has received inquiries from brewers regarding the labeling standards that apply to beers produced from substitutes for malted barley, such as rice or corn. We also have fielded questions from brewers and importers regarding the appropriate labeling of beers that are made without hops. This ruling explains the statutory criteria for classification of products as “beer” and “malt beverages” under the applicable laws and regulations. Laws and Regulations Federal Alcohol Administration Act Sections 105(e) and (f) of the Federal Alcohol Administration Act (FAA Act), 27 U.S.C. 205(e) and (f), vest broad authority in the Secretary of the Treasury to prescribe regulations with respect to the labeling and advertising of wine, distilled spirits, and malt beverages that are introduced into interstate or foreign commerce or imported into the United States. Section 105(e) also provides that no person may bottle, or remove from customs custody in bottles, distilled spirits, wine, or malt beverages unless he has obtained a certificate of label approval issued in accordance with regulations prescribed by the Secretary. -

Microbiology Immunology Cent

years This booklet was created by Ashley T. Haase, MD, Regents Professor and Head of the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, with invaluable input from current and former faculty, students, and staff. Acknowledgements to Colleen O’Neill, Department Administrator, for editorial and research assistance; the ASM Center for the History of Microbiology and Erik Moore, University Archivist, for historical documents and photos; and Ryan Kueser and the Medical School Office of Communications & Marketing, for design and production assistance. UMN Microbiology & Immunology 2019 Centennial Introduction CELEBRATING A CENTURY OF MICROBIOLOGY & IMMUNOLOGY This brief history captures the last half century from the last history and features foundational ideas and individuals who played prominent roles through their scientific contributions and leadership in microbiology and immunology at the University of Minnesota since the founding of the University in 1851. 1. UMN Microbiology & Immunology 2019 Centennial Microbiology at Minnesota MICROBIOLOGY AT MINNESOTA Microbiology at Minnesota has been From the beginning, faculty have studied distinguished from the beginning by the bacteria, viruses, and fungi relevant to breadth of the microorganisms studied important infectious diseases, from and by the disciplines and sub-disciplines early studies of diphtheria and rabies, represented in the research and teaching of through poliomyelitis, streptococcal and the faculty. The Microbiology Department staphylococcal infection to the present itself, as an integral part of the Medical day, HIV/AIDS and co-morbidities, TB and School since the department’s inception cryptococcal infections, and influenza. in 1918-1919, has been distinguished Beyond medical microbiology, veterinary too by its breadth, serving historically microbiology, microbial physiology, as the organizational center for all industrial microbiology, environmental microbiological teaching and research microbiology and ecology, microbial for the whole University. -

Further Study on the Affordability of Alcoholic

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and EDUCATION AND THE ARTS decisionmaking through research and analysis. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from www.rand.org as a public INFRASTRUCTURE AND service of the RAND Corporation. TRANSPORTATION INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND TERRORISM AND Browse Reports & Bookstore HOMELAND SECURITY Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Europe View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation technical report series. Reports may include research findings on a specific topic that is limited in scope; present discussions of the methodology employed in research; provide literature reviews, survey instru- ments, modeling exercises, guidelines for practitioners and research professionals, and supporting documentation; or deliver preliminary findings. All RAND reports un- dergo rigorous peer review to ensure that they meet high standards for research quality and objectivity.