Seattle Trademark History Tour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History and Decline of Ostrea Lurida in Willapa Bay, Washington Author(S): Brady Blake and Philine S

The History and Decline of Ostrea Lurida in Willapa Bay, Washington Author(s): Brady Blake and Philine S. E. Zu Ermgassen Source: Journal of Shellfish Research, 34(2):273-280. Published By: National Shellfisheries Association DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2983/035.034.0208 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.2983/035.034.0208 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Journal of Shellfish Research, Vol. 34, No. 2, 273–280, 2015. THE HISTORY AND DECLINE OF OSTREA LURIDA IN WILLAPA BAY, WASHINGTON BRADY BLAKE1 AND PHILINE S. E. ZU ERMGASSEN2* 1Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife, 375 Hudson Street, Port Townsend, WA 98368; 2Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 3EJ, United Kingdom ABSTRACT With an annual production of 1500 metric tons of shucked oysters, Willapa Bay, WA currently produces more oysters than any other estuary in the United States. -

Richard Russell, the Senate Armed Services Committee & Oversight of America’S Defense, 1955-1968

BALANCING CONSENSUS, CONSENT, AND COMPETENCE: RICHARD RUSSELL, THE SENATE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE & OVERSIGHT OF AMERICA’S DEFENSE, 1955-1968 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Joshua E. Klimas, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor David Stebenne, Advisor Professor John Guilmartin Advisor Professor James Bartholomew History Graduate Program ABSTRACT This study examines Congress’s role in defense policy-making between 1955 and 1968, with particular focus on the Senate Armed Services Committee (SASC), its most prominent and influential members, and the evolving defense authorization process. The consensus view holds that, between World War II and the drawdown of the Vietnam War, the defense oversight committees showed acute deference to Defense Department legislative and budget requests. At the same time, they enforced closed oversight procedures that effectively blocked less “pro-defense” members from influencing the policy-making process. Although true at an aggregate level, this understanding is incomplete. It ignores the significant evolution to Armed Services Committee oversight practices that began in the latter half of 1950s, and it fails to adequately explore the motivations of the few members who decisively shaped the process. SASC chairman Richard Russell (D-GA) dominated Senate deliberations on defense policy. Relying only on input from a few key colleagues – particularly his protégé and eventual successor, John Stennis (D-MS) – Russell for the better part of two decades decided almost in isolation how the Senate would act to oversee the nation’s defense. -

North America CANADA

North America CANADA Gallons Guzzled 17.49 Gal Per Person Per Year Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site Alberta Calgary Big Rock Brewery McNally's Ale Dec-01 15.5 5.0% Gary B. www.bigrockbeer.com Cold Cock Winter Porter May-09 17.0 Gary B. Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site British Columbia Pacific Western Brewing Prince George Bulldog Canadian Lager May-09 16.0 Helen B. Company Vancouver Molson Breweries Molson Canadian Lager May-05 17.0 5.0% Helen B. Vancouver Island Brewing Vancouver Piper's Pale Ale May-09 16.0 Helen B. Company Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site Manitoba Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site New Brunswick Saint John Moosehead Brewery Moosehead Lager Jul-01 17.0 5.1% Gary B. Moosehead Light Lager Sep-09 15.0 4.8% Maurice S. Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site New Foundland St. John's Labatt Brewing Company Budweiser Lager Sep-02 18.0 5.0% Gary B. Bud Light Lager Sep-02 16.0 4.0% Gary B. St. John's Molson Brewery L.T.D. Black Horse Lager Sep-02 18.5 5.0% Gary B. Molson Canadian Lager Sep-09 17.5 5.0% Maurice S. Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site Northwest Territories Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site Nova Scotia Halifax Labatt Brewing Company Labatt's Blue Pilsner Set-02 16.0 4.3% Maurice S. -

Congressional Mail Logs for the President (1)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 8, folder “Congress - Congressional Mail Logs for the President (1)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. r Digitized from Box 8 of The John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library Presi dent's Mail - May 11, 1976 House 1. Augustus Hawkins Writes irr regard to his continuing · terest in meeting with the President to discuss the· tuation at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission prior to the appoint ment of a successor to Chairman owell W. Perry. 2. Larry Pressler Says he will vote to sustain e veto of the foreign military assistance se he believes the $3.2 billion should be u ed for nior citizens here at horne. 3. Gus Yatron Writes on behalf of Mrs. adys S. Margolis concerning the plight of Mr. Mi ail ozanevich and his family in the Soviet Union. 4. Guy Vander Jagt Endorses request of the TARs to meet with the President during their convention in June. -

Major Office Specialty (Area 280) 2015 Revaluation

Major Office Specialty (Area 280) 2015 Revaluation Department of Assessments Commercial Appraisal Office Specialty 280- 20 DENNY REGRADE - LAKE UNION - FREMONT 280- 10 SEATTLE CBD 280- 40 WATERFRONT - PILL HILL 280- 30 PIONEER SQUARE - SOUTH SEATTLE 280- 50 BELLEVUE - EASTSIDE 20 40 10 30 50 280- 60 NORTH-EAST-SOUTH 280- 60 NORTH-EAST-SOUTHC COOUNNTYTY The information included on this map has been compiled by King County staff from a variety of sources and is subject to change without notice. King County makes no representations or warranties, express or implied, as to accuracy, completeness, timeliness, or rights to the use of such information. This document is not intended for use as a survey product. King County shall not be liable for any general, special, indirect, incidental, or consequential damages including, but not limited to, lost revenues or lost profits resulting from the use or misuse of the information contained on this map. King County Any sale of this map or information on this map is prohibited except by written permission of King County. Dept. of Assessments C:\Data\data\Commercial\Commercial_Areas\Specialtyedits.mxd King County Department of Assessments King County Administration Bldg. Lloyd Hara 500 Fourth Avenue, ADM-AS-0708 Seattle, WA 98104-2384 Assessor (206) 296-5195 FAX (206) 296-0595 Email: [email protected] As we start preparations for the 2015 property assessments, it is helpful to remember that the mission and work of the Assessor’s Office sets the foundation for efficient and effective government and is vital to ensure adequate funding for services in our communities. -

Olympia Oyster (Ostrea Lurida)

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Olympia Oyster Ostrea lurida in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2011 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2011. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Olympia Oyster Ostrea lurida in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xi + 56 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous report(s): COSEWIC. 2000. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Olympia Oyster Ostrea conchaphila in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 30 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) Gillespie, G.E. 2000. COSEWIC status report on the Olympia Oyster Ostrea conchaphila in Canada in COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Olympia Oyster Ostrea conchaphila in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-30 pp. Production note: COSEWIC acknowledges Graham E. Gillespie for writing the provisional status report on the Olympia Oyster, Ostrea lurida, prepared under contract with Environment Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada. The contractor’s involvement with the writing of the status report ended with the acceptance of the provisional report. Any modifications to the status report during the subsequent preparation of the 6-month interim and 2-month interim status reports were overseen by Robert Forsyth and Dr. Gerald Mackie, COSEWIC Molluscs Specialist Subcommittee Co-Chair. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur l’huître plate du Pacifique (Ostrea lurida) au Canada. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - SENATE March 31 of Staff; Without Amendment (Rept

3144 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - SENATE March 31 of Staff; without amendment (Rept. No. to the Committee on Post Ofiice and Civil H. Con. Res. 206. Concurrent resolution 1666). Referred to the House Calendar. Service. favoring the granting of the status of per Mr. SABATH: C9mmittee on Rules. House By Mr. STOCKMAN: inanent residence to certain aliens; to the Resolution 532. Resolution to direct the H. R. 7297. A bill to prevent Federal dam Committee on the Judiciary. Committee on Education and Labor to con and reservoir projects from interfering with duct an investigation of the Wage Stabili sustained-yield timber operations; to the zation Board; with amendment (Rept. No. Committee on Public Works. PETITIONS, ETC. 1667). Referred to the House Calendar. By Mr. WILLIAMS of Mississippi: Mr. SABATH: Committee on Rules. House H. R. 7298. A bill to authorize the consoli Under clause 1 of rule XXII, petitions Resolution 520. Resolution creating a se dation of the area of Vicksburg National Mili and papers were laid on the Clerk's desk lect committee to conduct an investiga tary Park, in the State of Mississippi, and for and referred as follows: tion and study of offensive and undesirable other purposes; to the Committee on Interior 658. By Mr. SMITH of Wisconsin: Petition books and radio and television programs; and Insular Affairs. of the Milwaukee Cooperative Milk Produc without amendment (Rept. No. 1668). Re ers. Over 1,000 people were present at the ferred to the House Calendar. annual meeting on March 11, 1952, to go on Mr. MADDEN: Committee on Rules. House MEMORIALS record opposing universal military service as Resolution 591. -

The Boeing Company and the Militarymetropolitanindustrial

1/3/2017 Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest About Us Events Classroom Materials Pacific Northwest Resources Quarterly The Boeing Company and the MilitaryMetropolitanIndustrial Complex, 19451953 Richard S. Kirkendall Pacific Northwest Quarterly 85:4 (Oct. 1994), p. 137149 This Boeing bomber embodies the transition to jet aircraft and the dependence on military that characterized company operations during the years following World War II. (Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Negative #10703. Photo by Boeing Company) The years of Harry Truman's presidency were crucial to the success of the Boeing Airplane Company. The president himself did not have close ties with the firm or great confidence in air power, but one part of the American state the air forcerecognized Boeing's ability to serve air force interests and was in a stronger position than ever before to pursue those interests. Furthermore, the company now had another ally willing to enter the political arena on its behalf. This was Seattle. The people there had a new commitment to Boeing. Taking advantage of cold war fears, air force leaders lobbied for funds to be spent on bombers, and Seattle people worked to draw that money to their city by way of Boeing. As a consequence of the successes of these two groups in the Truman years, the company acquired the resources it needed to become the world leader in building commercial jets. In battling for Boeing, Seattle participated in what President Dwight D. Eisenhower later called the "military industrial complex." A historian, Roger Lotchin, recently proposed "metropolitanmilitary complex" as a substitute for Eisenhower's term. -

Estimating Basin Effects Using M9 and Recent Research for Tall Building Design in Seattle

Estimating Basin Effects Using M9 and Recent Research for Tall Building Design in Seattle COSMOS Technical Session Susan Chang, Ph.D., P.E. I November 16, 2018 1 Seattle Basin Data courtesy of Richard Blakely 2 Tall Buildings in Seattle (100+ m, 328+ ft) Columbia Center Rainier Square Tower 1984, 933 ft 2020, 850 ft Russell Investments Center F5 Tower 2006, 598 ft 2017, 660 ft 1201 3rd Avenue 1988, 772 ft Smith Tower 1914, 462 ft Background Source: www.skyscrapercenter.com/city/seattle 31 buildings 31 buildings Figure from Doug Lindquist, Hart Crowser 3 March 4, 2013 Workshop Chang, S.W., Frankel., A.D., and Weaver, C.S., 2014, RePort on WorkshoP to IncorPorate Basin ResPonse in the Design of Tall Buildings in the Puget Sound Region, Washington: U.S. Geological Survey OPen-File RePort 20- 14-1196, 28 P., httPs://Pubs.usgs.gov/of/2014/1196/ • Basin amPlification factors from crustal ground motion models (amplification factors a function of Z2.5 and Z1.0) • ApPlied to MCER from PSHA for all EQ source tyPes Photo by Doug Lindquist, Hart Crowser 4 Recent Research Effect of DeeP Basins on Structural CollaPse During Large Subduction Earthquakes By Marafi, Eberhard, Berman, Wirth, and Frankel, Earthquake SPectra, August 2017 • Basin amPlification factors for sites with Z2.5 > 3 km Marafi et al. (2017) 5 Recent Research Observed amPlification of sPectral resPonse values for stiff sites in Seattle Basin referenced to Seward Park station – thin soil over firm rock 2003 under OlymPics, M4.8 outside of basin 2001 near SatsoP, M5.0 6 Recent Research Broadband Synthetic Seismograms for Magnitude 9 Earthquakes on the Cascadia Megathrust Based on 3D Simulations and Stochastic Synthetics (Part 1): Methodology and Overall Results By Frankel, Wirth, Marafi, Vidale, and StePhenson, submitted to BSSA January 2018, comPleted USGS internal review 7 USGS/SDCI March 22, 2018 Workshop Attendees Peer reviewers Geotechnical Consultants • C.B. -

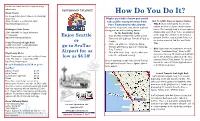

How Do You Do

Schedule information listed here is subject to change without notice. JEFFERSON TRANSIT Kitsap Transit How Do You Do It? Bus transportation from Poulsbo to the Bainbridge Island Ferry Maybe you didn’t know you could (360) 697-2877 or 1-(800)-501-7433 take public transportation from Get To LINK Pioneer Square Station: http://www.kitsaptransit.com Port Townsend to the airport. WALK: If you travel lightly, it is an easy You can! It’s inexpensive, easy, almost as fast as walk to the Pioneer Square Station transit Washington State Ferries driving your car and no parking hassles! tunnel. The least hilly walk is to turn right on (206) 464-6400 for Seattle information To the Bainbridge Ferry: Alaskan Way and left on Yesler, as indicated on the map. The entrance to the tunnel is 511 Statewide Enjoy Seattle From the Haines Place Park & Ride in Port http://www.wsdot.wa.gov/ferries Townsend, take Jefferson Transit’s #7 bus to just past 2nd Ave, next to Smith Tower. En- or Poulsbo. ter the bus tunnel at 2nd Ave. and Yesler Sound Transit (Link Light Rail) Way. 1-(800) 201-4900 1-(888)-889-6368 At the end of the line, transfer to Kitsap go to SeaTac Transit’s #90 Express bus to the Bainbridge http://www.soundtransit.org BUS: If you take the walkway to the1st & Ferry Terminal. Airport for as Marion “Southbound Stop”, Metro’s #99 King County Metro Then walk on the ferry – it’s free when you make the eastbound crossing. bus comes by every 30 minutes and will take Public Transportation for Seattle and King County low as $6.50! you to 5th & Jackson, adjacent to the Inter- (206) 553-3000 or 1-(800)-542-7876 Once in downtown Seattle, take Sound Transit’s national District Train Station. -

Trouble Brewing

" " " " " Trouble"Brewing:"" Brewers’"Resistance"to"Prohibition"and"Anti: German"Sentiment" " " " " " Daniel'Aherne' " " " Honors"Thesis"Submitted"to"the" Department"of"History,"Georgetown"University" Advisor:"Professor"Joseph"McCartin" Honors"Program"Chair:"Professor"Amy"Leonard" " " " 9"May"2016" 1" " Table of Contents Acknowledgements 4 I."Introduction 5 Why Beer 5 Prohibition in Europe 6 Early Temperance and State Prohibition in United States 8 Historical Narratives of Temperance and Prohibition 18 Brewers’ Muted Response 22 II. When Beer is Bier It’s Hard to Bear: How America’s Beer Became German 27 Lager Beer’s Inescapable German Identity 32 III."Band of Brewers: Industrial Collective Action in Brewers’ Associations 40 United States Brewers’ Association and the Origins of Brewer Cooperation and Lobbying 43 The USBA, Arthur Brisbane, and the Washington Times 48 Brotherly Brewing: A Brief History of Brewing in Philadelphia and Pennsylvania 56 “Facts Versus Fallacies”: Brewers Set the Record Straight 63 Popular Response After the War 68 Brewers and Labor: A Marriage of Necessity 72 Conclusions on Competition and Collective Action 78 IV. A King Without a Throne: Anheuser-Busch’s Struggle to Stave off Prohibition 80 How French St. Louis Became a Land of Germans and Beer 83 The Rise of Anheuser-Busch 89 Early Brand Advertising 94 Anheuser-Busch Changes Its Tune 97 V. From Drought to Draught: The Return of Beer and the End of the Great American Hangover 107 Beer and Volstead 110 Brewers’ During Prohibition 113 Conclusion 118 Epilogue 123 -

From British Columbia to Baja California Restoring the Olympia Oyster (Ostrea Lurida)

From British Columbia to Baja California Restoring The Olympia Oyster (Ostrea lurida) Report of a Forum Sponsored by American Honda Motor Corporation Aquarium of the Pacific Bren School of the University of California, Santa Barbara 16-17 March 2017 Acknowledgements We thank the Bren Oyster Group, all of the other presenters, and those who authored sections of this report. We thank the Bren students for acting as rapporteurs and for their excellent notes. We also thank Linda Brown for handling the logistics from start to finish and for helping assemble the sections of this report. We also thank Linda Brown and Claire Atkinson for editing the report. Jerry R. Schubel, Aquarium of the Pacific Steven Center, American Honda Motor Co., Inc. Hunter Lenihan, UC Santa Barbara This report can be found at: http://www.aquariumofpacific.org/mcri/info/restoring_the_olympia_oyster/forums 2 Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 5 Insights from the forum ......................................................................................................... 9 Action Items ....................................................................................................................... 11 Planning and Incentivizing Native Olympia Oyster Restoration in SoCal ........................... 13 Restoration of Native Oysters in San Francisco Bay .......................................................... 21 Restoration of Native Oysters in