Boats to Burn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spirited Seafarers WANDERLUST / Malay Archipelago

ISSUE 128 MAR 2018 Sail through my pages but keep me on this ship. Read me online. AirAsia Inflight Magazine The Bajau Laut Spirited Seafarers WANDERLUST / Malay Archipelago Nomads of WORDS & PHOTOGRAPHY: Claudio Sieber/ theclaudiosieberphotography.com Sulu Sea Living on the water, moving from island to island, and sometimes settling along the coastal areas of the Malay Archipelago (though concentrated in the area of the Sulu Sea), the seafaring Bajau Laut live a simple life in some of the most enchanting places on earth. The charming Bajau Laut wooden stilt huts can accommodate anywhere between a family of four or five to a small community encompassing about 30 roommates. These stilt houses, which usually take three weeks to erect, are equipped with only basic necessities. 1. Pictured here is Nalu, a Bajau Laut who migrated from the Philippines 26 years ago. A self- taught carpenter, he can easily design a fishing boat in about a week all by himself, without even an initial sketch to go by. The traditional craft of boat building is passed down from generation to generation. 2. A young Bajau Laut boy flies a home-made kite in the stilt village of Bangau-Bangau, Semporna, Sabah. The simple kite is constructed from a plastic bottle, plastic material, bamboo string and a rope. 3. A stunning vista enjoyed by the Bajau Laut who roam the seas. As a result of comprehensive conservation efforts by Sabah Parks authorities, the reefs at Tun Sakaran Marine Park remain pristine, allowing marine life to flourish. Pictured here is Pulau 1 Bodgaya (Bodgaya Island), the largest among the eight islands within the marine park, which is a prime site for snorkelling 03 and hiking. -

Universitat Pompeu Fabra Estrategias Filipinas Respecto a China

^ ui' °+ «53 T "" Biblioteca Universitat Pompeu Fabra Tesis doctoral Estrategias filipinas respecto a China: Alonso Sánchez y Domingo Salazar en la empresa de China (1581-1593) Barcelona, 1998 Volumen 1 Autor: Manel Ollé Rodríguez Directora: Dolors Folch Fornesa Documento 12 Autor: Alonso Sánchez Lugar y fecha: Manila, 1585 Localización: AGÍ Filipinas 79, ARAH Jesuitas. tomo VII y ANM, Colección Fernández Navarrete, II, fol. 253, dto. 8o.256 2^6 Se reproduce en esta edición el manuscrito localizado en ANM, Colección Fernández Navarrete, II, fol. 253, dto. 8o 238 Relación brebe de la jornada que hizo el P. Alonso Sánchez la segunda vez que fué a la China el año 1584. 257 En el año del582 habiendo yo ido a la China y Macan sobre negocios tocantes a la Gloria de Dios y al servicio de su magestad, por lo que el gobernador D. Gonzalo Ronquillo pretendía y deseaba de reducir aquella ciudad y puerto de portugueses a la obediencia de Su magestad, cuyos eran ya los reynos de Portugal. Pretendían esto el gobernador y obispo y capitanes y las religiones de todas estas yslas, por parecerles que no había otro camino para la entrada de cosa tan dificultosa y deseada como la China, sino era por aquella puerta, principalmente si se hubiese de hacer por vía de guerra, como el gobernador y los seculares pretendían y todos entienden que es el medio por el qual se puede hacer algo con brebedad y efecto. Hízose lo que se deseaba, juntándose con el Capitán Mayor y obispo y electos y las religiones y jurando a su Magestad, por su Rey y Señor natural, de lo qual y de otras cosas importantes dieron al P. -

![Archipel, 100 | 2020 [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 30 Novembre 2020, Consulté Le 21 Janvier 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8932/archipel-100-2020-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-30-novembre-2020-consult%C3%A9-le-21-janvier-2021-398932.webp)

Archipel, 100 | 2020 [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 30 Novembre 2020, Consulté Le 21 Janvier 2021

Archipel Études interdisciplinaires sur le monde insulindien 100 | 2020 Varia Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/archipel/2011 DOI : 10.4000/archipel.2011 ISSN : 2104-3655 Éditeur Association Archipel Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 décembre 2020 ISBN : 978-2-910513-84-9 ISSN : 0044-8613 Référence électronique Archipel, 100 | 2020 [En ligne], mis en ligne le 30 novembre 2020, consulté le 21 janvier 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/archipel/2011 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/archipel.2011 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 21 janvier 2021. Association Archipel 1 SOMMAIRE In Memoriam Alexander Ogloblin (1939-2020) Victor Pogadaev Archipel a 50 ans La fabrique d’Archipel (1971-1982) Pierre Labrousse An Appreciation of Archipel 1971-2020, from a Distant Fan Anthony Reid Echos de la Recherche Colloque « Martial Arts, Religion and Spirituality (MARS) », 15 et 16 juillet 2020, Institut de Recherches Asiatiques (IRASIA, Université d’Aix-Marseille) Jean-Marc de Grave Archéologie et épigraphie à Sumatra Recent Archaeological Surveys in the Northern Half of Sumatra Daniel Perret , Heddy Surachman et Repelita Wahyu Oetomo Inscriptions of Sumatra, IV: An Epitaph from Pananggahan (Barus, North Sumatra) and a Poem from Lubuk Layang (Pasaman, West Sumatra) Arlo Griffiths La mer dans la littérature javanaise The Sea and Seacoast in Old Javanese Court Poetry: Fishermen, Ports, Ships, and Shipwrecks in the Literary Imagination Jiří Jákl Autour de Bali et du grand Est indonésien Śaivistic Sāṁkhya-Yoga: -

BAB I PENDAHULUAN A. Dasar Pemikiran Bangsa Indonesia Sejak

1 BAB I PENDAHULUAN A. Dasar Pemikiran Bangsa Indonesia sejak dahulu sudah dikenal sebagai bangsa pelaut yang menguasai jalur-jalur perdagangan. Sebagai bangsa pelaut maka pengetahuan kita akan teknologi perkapalan Nusantara pun seharusnya kita ketahui. Catatan-catatan sejarah serta bukti-bukti tentang teknologi perkapalan Nusantara pada masa klasik memang sangatlah minim. Perkapalan Nusantara pada masa klasik, khususnya pada masa kerajaan Hindu-Buddha tidak meninggalkan bukti lukisan-lukisan bentuk kapalnya, berbeda dengan bangsa Eropa seperti Yunani dan Romawi yang bentuk kapal-kapal mereka banyak terdapat didalam lukisan yang menghiasi benda porselen. Penemuan bangkai-bangkai kapal yang berasal dari abad ini pun tidak bisa menggambarkan lebih lanjut bagaimana bentuk aslinya dikarenakan tidak ditemukan secara utuh, hanya sisa-sisanya saja. Sejak kedatangan bangsa Eropa ke Nusantara pada abad ke 16, bukti-bukti mengenai perkapalan yang dibuat dan digunakan di Nusantara mulai terbuka. Catatan-catatan para pelaut Eropa mengenai pertemuan mereka dengan kapal- kapal Nusantara, serta berbagai lukisan-lukisan kota-kota pelabuhan di Nusantara yang juga dibuat oleh orang-orang Eropa. Sejak abad ke-17, di Eropa berkembang seni lukis naturalistis, yang coba mereproduksi keadaan sesuatu obyek dengan senyata mungkin; gambar dan lukisan yang dihasilkannya membahas juga pemandangan-pemandangan kota, benteng, pelabuhan, bahkan pemandangan alam 2 di Asia, di mana di sana-sini terdapat pula gambar perahu-perahu Nusantara.1 Catatan-catatan Eropa ini pun memuat nama-nama dari kapal-kapal Nusantara ini, yang ternyata sebagian masih ada hingga sekarang. Dengan menggunakan cacatan-catatan serta lukisan-lukisan bangsa Eropa, dan membandingkan bentuk kapalnya dengan bukti-bukti kapal yang masih digunakan hingga sekarang, maka kita pun bisa memunculkan kembali bentuk- bentuk kapal Nusantara yang digunakan pada abad-abad 16 hingga 18. -

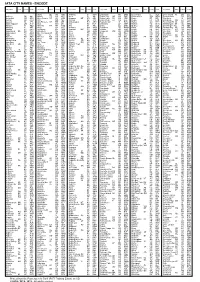

Iata City Names - Encode

IATA CITY NAMES - ENCODE City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code Alpha QL AU ABH Aribinda BF XAR Bakelalan MY BKM Beersheba IL BEV Block Island RI US BID Aalborg DK AAL Alpine TX US ALE Arica CL ARI Baker City OR US BKE Befandriana MG WBD Bloemfontein ZA BFN Aalesund NO AES Alroy Downs NT AU AYD Aripuana MT BR AIR Baker Lake NU CA YBK Beica ET BEI Blonduos IS BLO Aarhus DK AAR Alta NO ALF Arkalyk KZ AYK Bakersfield CA US BFL Beida LY LAQ Bloodvein MB CA YDV Aasiaat GL JEG Alta Floresta MT BR AFL Arkhangelsk RU ARH Bakkafjordur IS BJD Beihai CN BHY Bloomfield Ri QL AU BFC Aba/Hongyuan CN AHJ Altai MN LTI Arlit NE RLT Bakouma CF BMF Beihan YE BHN Bloomington IN US BMG Abadan IR ABD Altamira PA BR ATM Arly BF ARL Baku AZ BAK Beijing CN BJS Bloomington-NIL US BMI Abaiang KI ABF Altay CN AAT Armenia CO AXM Balakovo RU BWO Beira MZ BEW Blubber Bay BC CA XBB Abakan XU ABA Altenburg DE AOC Armidale NS AU ARM Balalae SB BAS Beirut LB BEY Blue Bell PA US BBX Abbotsford BC CA YXX Altenrhein CH ACH Arno MH AMR Balgo Hill WA AU BQW Bejaia DZ BJA Bluefield WV US BLF Abbottabad PK AAW Alto Rio Seng CB AR ARR Aroa PG AOA Bali CM BLC Bekily MG OVA Bluefields NI BEF Abbs YE EAB Alton IL US ALN Arona SB RNA Bali PG BAJ Belaga MY BLG Blumenau SC BR BNU Abeche TD AEH Altoona PA US AOO Arorae KI AIS Balikesir TR BZI Belem PA BR BEL Blythe CA US BLH Abemama KI AEA Altus OK US LTS Arrabury QL AU AAB Balikpapan ID BPN Belfast GB -

50000000 Housing Project for Southeast Matawan Township

MQ3KDUTH C O . HISTORICAL A SSS.,- FSBEHOLD* #.J. 'P,': f ’ ■ .... f;: . $50,000,000 Housing Project Street Signs. For IWarlboro Township Paul T. Caliill ’’Miss Rheingold” At Cliffwood Beach Buys Company For Southeast Matawan Township Cliffwood Beach Co., Frederick Weiuel, chairman of the Matawan Tpwuship' Planning Real Estate Firm, Sold Board, disclosed last night that a Coin-Boxing Barred P a u l T hom as C ahill, 157 N ether- developer who will adhere to the Matawan Is Key wood Dr., Cliffwood Beach, has lWM>y-150-foot m inim um lot a iie Chief Jeha J. Flood, Mata purchased the real estate bus|. Is In te reste d in buying up 1500 waa Police, aald yesterday he In Sterner Plan ness of the Cliffwood Beach Co., acres in the southeasterly section had received a directive from k s b e r t W arw ick, M onm outh Inc., from the Estates of Samuel of the township. At somewhat less Planning Chairman D. Walker and Charles W. Mor. than three houses to the acre, this Ceuaty traffic safety co-ordl- aatar, that all solidtalioni for Resubmits To State risey and has formed tlie Caliill would be a 3000-to-t000 hom esite Co. Officers of the new i^tjipany development. Tlie houses w ould be charitable or public service Matawan Station and the Mat are Mr. Cahill, president; Everett priced in the - >15.000 range, ic- purposes from motorists oa hlghwaya must stop. - The di awan Township-ftarilan area near II. Larrison, Broadwly, Keyport, cording to Mr. Wenzel, making tt vice president; Lillian A. -

Cecilia Noguez

Cecilia Noguez Curriculum Vitae 9 de marzo de 2018 9 de marzo de 2018 Curriculum Vitae: Cecilia Noguezp agina´ ii Contents DATOS GENERALES 1 FORMACION´ ACADEMICA´ 1 EXPERIENCIA PROFESIONAL 1 Campo de especialidad 1 Puestos academicos´ en investigacion´ 2 Puestos academicos´ en docencia 2 MEMBRESIAS EN SOCIEDADES CIENT´IFICAS 2 PARTICIPACION´ EN ORGANOS´ COLEGIADOS 3 Organos´ colegiados en la UNAM 3 Organos´ colegiados nacionales e internacionales 3 Organizacion´ de reuniones cient´ıcas nacionales e internacionales 4 Agencias de apoyo a la investigacion´ cient´ıca como arbitro´ regular 4 PARTICIPACION´ EDITORIAL 4 Trabajo editorial 4 Arbitro regular de las siguientes revistas internacionales 5 PREMIOS, RECONOCIMIENTOS Y DISTINCIONES 5 Premios y distinciones academicas´ 5 Otros reconocimientos academicos´ 6 Sistema Nacional de Investigadores (SNI) y Est´ımulos academicos´ UNAM (PRIDE) 7 Becas 7 CONFERENCIAS, SEMINARIOS Y COLOQUIOS (315) 7 Por invitacion´ (178) 7 – Platicas´ invitadas internacionales 7 – Platicas´ invitadas nacionales 12 – Platicas´ de divulgacion´ 15 Presentaciones regulares en congresos (137) 16 PROYECTOS FINANCIADOS 16 Responsable (16) 16 9 de marzo de 2018 Curriculum Vitae: Cecilia Noguezp agina´ iii Corresponsable (4) 17 Participante (12) 17 FORMACION´ DE RECURSOS HUMANOS 17 Cursos Docentes (54) 17 Tesis y posdoctorantes 18 – Finalizados (23) 19 – En proceso (3) 22 Participacion´ en examenes´ de grado como sinodal (38) 22 Participacion´ en examenes´ generales y predoctorales (6) 24 PRODUCCION´ CIENT´IFICA (96) 24 Tabla -

Analisis Investasi Perahu Sandeq Bermaterial Kayu Dengan Wilayah

SKRIPSI ANALISIS INVESTASI PERAHU SANDEQ BERMATERIAL KAYU DENGAN WILAYAH OPERASIONAL PANGALI-ALI - PAROMPONG Diajukan Kepada Fakultas Teknik Universitas Hasanuddin Untuk Memenuhi Sebagian Persyaratan Guna Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Teknik Oleh : ANDI MAHIRA MH D311 16 506 DEPARTEMEN TEKNIK PERKAPALAN FAKULTAS TEKNIK UNIVERSITAS HASANUDDIN GOWA 2021 iii KATA PENGANTAR Segala puji syukur bagi Allah SWT yang senantiasa memberikan jalan yang terbaik bagi umatnya. Allah SWT mengajarkan kepada manusia apa – apa yang tidak diketahuinya. Shalawat dan salam untuk baginda Rasulullah SAW. Atas Berkat Rahmat Allah SWT sehingga walaupun keterbatasan dan kelemahan yang penulis miliki, akhirnya skripsi ini dapat terselesaikan. Pada kesempatan ini penulis ingin menghaturkan terima kasih terutama kepada Kedua Orang Tua Tercinta, terutama Ibunda saya, yang selalu senantiasa berjuang, berusaha mendampingi saya, pengertian terhadap saya dan Saudara- Saudari saya yang berjumlah 13 orang atas segala jerih payah, doa dan dukungannya baik moril maupun materil sehingga penulis dapat menyelesaikan studi pada Departemen Teknik Perkapalan FT-UH. Ungkapan terima kasih yang amat tinggi juga penulis sampaikan kepada: 1. Ibu Dr. Andi Sitti Chaerunnisa M, ST, MT selaku dosen pembimbing I, terima kasih banyak atas bimbingan dan arahannya selama ini. 2. Ibu Dr. Ir. Hj. Misliah MS.Tr selaku dosen pembimbing II, terima kasih banyak atas bimbingan dan arahannya selama ini. 3. Bapak Ir. Lukman Bochary, MT, selaku penguji, terima kasih atas arahannya. iv 4. Ibu Wihdat Djafar, ST. MT., MlogsupChMgmt , selaku penguji, terima kasih atas arahannya. 5. Bapak Dr. Eng. Suandar Baso, ST., MT, selaku Ketua Departemen Teknik Fakultas Teknik Universitas Hasanuddin atas segala ilmu dan bantuannya. 6. Bapak/Ibu dosen dan staff Departemen Teknik Perkapalan Fakultas Teknik Universitas Hasanuddin atas segala ilmu dan bantuannya. -

Handbook Ng Miyembro/ Ebidensiya Ng Pagsaklaw Anthem Blue Cross Cal Mediconnect Plan (Medicare-Medicaid Plan)

Santa Clara County, CA 2020 Handbook ng Miyembro/ Ebidensiya ng Pagsaklaw Anthem Blue Cross Cal MediConnect Plan (Medicare-Medicaid Plan) Mayroong mga tanong? Tawagan kami sa 1-855-817-5785 (TTY: 711), Lunes hanggang Biyernes, 8 a.m. hanggang 8 p.m. Libre ang tawag na ito. O bumisita sa duals.anthem.com. H6229_20_110117_U_TA CMS Accepted 09/03/2019 5041103 501601CADTAABC 2020 CA MMP EOC_SC2020 CA MMP EOC_SC_DAO_CQ.indd 2 2019/9/18 14:05:04 H6229_20_110117_U_TA CMS Accepted 09/03/2019 500750CADTAABC Anthem Blue Cross Cal MediConnect Plan (Medicare-Medicaid Plan) Handbook ng Miyembro Enero 1, 2020 – Disyembre 31, 2020 Ang Saklaw ng Iyong Kalusugan at Gamot sa ilalim ng Anthem Blue Cross Cal MediConnect Plan Handbook ng Miyembro Panimula Sinasabi ng handbook na ito sa iyo ang tungkol sa iyong saklaw sa ilalim ng Anthem Blue Cross Cal MediConnect Plan hanggang Disyembre 31, 2020. Ipinapaliwanag nito ang mga serbisyo sa pangangalaga ng kalusugan, serbisyo sa kalusugan ng pag-uugali (kalusugang pangkaisipan at karamdaman dahil sa labis na paggamit ng droga o alak), saklaw sa inireresetang gamot, at mga pangmatagalang serbisyo at suporta. Tumutulong ang mga pangmatagalang serbisyo at suporta sa iyo upang manatili sa tahanan sa halip na pumunta sa isang nursing home o ospital. Binubuo ang mga pangmatagalang serbisyo at suporta ng Community-Based Adult Services (CBAS), Multipurpose Senior Services Program (MSSP), at mga Nursing Facility (NF). Makikita ang mga mahahalagang termino at ang kanilang mga kahulugan sa pagkakasunud-sunod ayon sa alpabeto sa huling kabanata ng Handbook ng Miyembro. Isa itong importanteng legal na dokumento. Mangyaring itabi ito sa isang ligtas na lugar. -

Remarks on the Terminology of Boatbuilding and Seamenship in Some Languages of Southern Sulawesi

This article was downloaded by:[University of Leiden] On: 6 January 2008 Access Details: [subscription number 769788091] Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Indonesia and the Malay World Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713426698 Remarks on the terminology of boatbuilding and seamanship in some languages of Southern Sulawesi Horst Liebner Online Publication Date: 01 November 1992 To cite this Article: Liebner, Horst (1992) 'Remarks on the terminology of boatbuilding and seamanship in some languages of Southern Sulawesi', Indonesia and the Malay World, 21:59, 18 - 44 To link to this article: DOI: 10.1080/03062849208729790 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03062849208729790 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article maybe used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Creole Drum. an Anthology of Creole Literature in Surinam

Creole drum An Anthology of Creole Literature in Surinam Jan Voorhoeve en Ursy M. Lichtveld bron Jan Voorhoeve en Ursy M. Lichtveld, Creole drum. An Anthology of Creole Literature in Surinam. Yale University Press, Londen 1975 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/voor007creo01_01/colofon.htm © 2006 dbnl / erven Jan Voorhoeve & erven Ursy M. Lichtveld vii Preface Surinam Creole (called Negro-English, Taki-Taki, and Nengre or more recently also Sranan and Sranan tongo) has had a remarkable history. It is a young language, which did not exist before 1651. It served as a contact language between slaves and masters and also between slaves from different African backgrounds and became within a short time the mother tongue of the Surinam slaves. After emancipation in 1863 it remained the mother tongue of lower-class Creoles (people of slave ancestry), but it served also as a contact language or lingua franca between Creoles and Asian immigrants. It gradually became a despised language, an obvious mark of low social status and lack of proper schooling. After 1946, on the eve of independence, it became more respected (and respectable) within a very short time, owing to the great achievements of Creole poets: Cinderella kissed by the prince. In this anthology we wish to give a picture of the rise and glory of the former slave language. The introduction sketches the history of Surinam Creole in its broad outlines, starting from the first published text in 1718. The texts are presented in nine chronologically ordered chapters starting from the oral literature, which is strongly reminiscent of the times of slavery, and ending with modern poetry and prose. -

Celestial Navigation As a Kind of Local Knowledge of the Makassar Ethnic: an Analysis of Arena Wati’S Selected Works

The 2013 WEI International Academic Conference Proceedings Istanbul, Turkey Celestial Navigation as a Kind of Local Knowledge of the Makassar Ethnic: An Analysis of Arena Wati’s Selected Works Sohaimi Abdul Aziz 1 and Sairah Abdullah 2 1School of Humanities, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia 2St. George's Girls' School, Penang, Malaysia. [email protected] Abstract Southeast Asia was known for its seafarers. Indeed, long before the Portuguese arrived in Asian waters, the seafarers had been sailing over the oceans for thousands of miles without a proper compass or written charts. Arena Wati or Muhammad Dahlan bin Abdul Biang is well-known author in Malaysia. He is one of the national laureates of Malay literature. Before he ventured into the world of creative writings, he was a seafarer since the age of 17. He originates from Makassar, an island of seafarers in Indonesia. His vast experiences as a seafarer, who learned and practiced the celestial navigational skills of the Makassar people, have become the important ingredient of his creative writings. Celestial navigation is a navigation of a naturalist that is based on natural elements such as wind direction, wave patterns, ocean currents, cloud formation and so on. Nevertheless, not much research has been doned on his navigational skills as reflected in his works, especially in the contact of local knowledge. As a result, this paper will venture into the celestial navigation and its relationship with the local knowledge. Selected works of Arena Wati, which consists of a memoir and two novels, will be analyzed using textual analysis. The result of this study reveals that the selected works of Arena Wati shows the importance of celestial navigation as part of the local knowledge.