REPORT for Stiefel Foundation Small Grant Award, 2009 PROJECT: Ecology of Slave-Maker Ants and Their Hosts: the Effect of Geogra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radiation in Socially Parasitic Formicoxenine Ants

RADIATION IN SOCIALLY PARASITIC FORMICOXENINE ANTS DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DES DOKTORGRADES DER NATURWISSENSCHAFTEN (D R. R ER . N AT .) DER NATURWISSENSCHAFTLICHEN FAKULTÄT III – BIOLOGIE UND VORKLINISCHE MEDIZIN DER UNIVERSITÄT REGENSBURG vorgelegt von Jeanette Beibl aus Landshut 04/2007 General Introduction II Promotionsgesuch eingereicht am: 19.04.2007 Die Arbeit wurde angeleitet von: Prof. Dr. J. Heinze Prüfungsausschuss: Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. S. Schneuwly 1. Prüfer: Prof. Dr. J. Heinze 2. Prüfer: Prof. Dr. S. Foitzik 3. Prüfer: Prof. Dr. P. Poschlod General Introduction I TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Six origins of slavery in formicoxenine ants 13 Introduction 15 Material and Methods 17 Results 20 Discussion 23 CHAPTER 2: Phylogeny and phylogeography of the Mediterranean species of the parasitic ant genus Chalepoxenus and its Temnothorax hosts 27 Introduction 29 Material and Methods 31 Results 36 Discussion 43 CHAPTER 3: Phylogenetic analyses of the parasitic ant genus Myrmoxenus 46 Introduction 48 Material and Methods 50 Results 54 Discussion 59 CHAPTER 4: Cuticular profiles and mating preference in a slave-making ant 61 Introduction 63 Material and Methods 65 Results 69 Discussion 75 CHAPTER 5: Influence of the slaves on the cuticular profile of the slave-making ant Chalepoxenus muellerianus and vice versa 78 Introduction 80 Material and Methods 82 Results 86 Discussion 89 GENERAL DISCUSSION 91 SUMMARY 99 ZUSAMMENFASSUNG 101 REFERENCES 103 APPENDIX 119 DANKSAGUNG 120 General Introduction 1 GENERAL INTRODUCTION Parasitism is an extremely successful mode of life and is considered to be one of the most potent forces in evolution. As many degrees of symbiosis, a phenomenon in which two unrelated organisms coexist over a prolonged period of time while depending on each other, occur, it is not easy to unequivocally define parasitism (Cheng, 1991). -

Recovery of Domestic Behaviors by a Parasitic Ant (Formica Subintegra) in the Absence of Its Host (Formica Subsericea)

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Spring 2019 Recovery of Domestic Behaviors by a Parasitic Ant (Formica Subintegra) in the Absence of Its Host (Formica Subsericea) Amber Nichole Hunter Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the Behavior and Ethology Commons, Entomology Commons, and the Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Hunter, Amber Nichole, "Recovery of Domestic Behaviors by a Parasitic Ant (Formica Subintegra) in the Absence of Its Host (Formica Subsericea)" (2019). MSU Graduate Theses. 3376. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3376 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECOVERY OF DOMESTIC BEHAVIORS BY A PARASITIC ANT (FORMICA SUBINTEGRA) IN THE ABSENCE OF ITS HOST (FORMICA -

Social Parasitism Among Ants at the E.S. George Reserve in Southern Michigan

The Great Lakes Entomologist Volume 12 Number 2 - Summer 1979 Number 2 - Summer Article 7 1979 June 1979 Social Parasitism Among Ants at the E.S. George Reserve in Southern Michigan Mary Talbot The Lindenwood Colleges Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Talbot, Mary 1979. "Social Parasitism Among Ants at the E.S. George Reserve in Southern Michigan," The Great Lakes Entomologist, vol 12 (2) Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol12/iss2/7 This Peer-Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Great Lakes Entomologist by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Talbot: Social Parasitism Among Ants at the E.S. George Reserve in Southe THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST SOCIAL PARASITISM AMONG ANTS AT 'THE E. S. GEORGE RESERVE IN SOUTHERN MICHIGAN Mary ~albotl A mode of life in which one species spends all or part of its existence in close contact with, and at the expense of, another species is rather common among ants. Sudd (1%7) stated that about one sixth of all known European species are parasitic to some extent. At the Edwin S. George Reserve in Livingston County, Michigan, 28.7% (25 of the 87 species) fall into the category of forms considered to be in some way parasitic on other ants. The following types of parasitism are found: (1) Dulosis, a kind of life in which workers of one species raid colonies of another species to bring back larvae and pupae that are reared to form a mixed colony where the imported "slaves" forage for food, build the nest, and care for the young, while the host workers carry on repeated raids. -

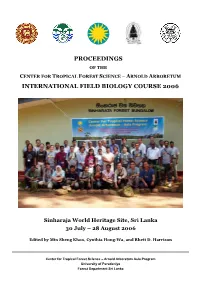

Proceedings of the CTFS-AA IFBC 2006

PROCEEDINGS OF THE CENTER FOR TROPICAL FOREST SCIENCE – ARNOLD ARBORETUM INTERNATIONAL FIELD BIOLOGY COURSE 2006 Sinharaja World Heritage Site, Sri Lanka 30 July – 28 August 2006 Edited by Min Sheng Khoo, Cynthia Hong-Wa, and Rhett D. Harrison Center for Tropical Forest Science – Arnold Arboretum Asia Program University of Peradeniya Forest Department Sri Lanka Cover photo: Organizers, resource staff and participants of the sixth CTFS-AA International Field Biology Course 2006 (IFBC-2006) at Sinharaja Forest Bungalow, after the opening ceremony on 31 July 2006. See more photos on page 9. Preface i Preface The CTFS-AA International Field Biology Course is an annual, graduate-level field course in tropical forest biology run by the Center for Tropical Forest Science – Arnold Arboretum Asia Program in collaboration with institutional partners in South and Southeast Asia. The CTFS-AA International Field Biology Course 2006 was held at Sinharaja World Heritage Area, Sri Lanka, from 30 July to 29 August and was hosted by the Forest Department, Sri Lanka, and the University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka. It was the sixth such course organized by CTFS-AA. Last year’s the course was held at Khao Chong, Thailand, and previous courses have been held in Malaysia. Next year’s course will be held at Xishuangbanna, Yunnan, China. The aim of these courses is to provide high-level training in the biology of forests in South and Southeast Asia. The courses are aimed at upper-level undergraduate and graduate students from the region, who are at the start of their thesis research or professional careers in forest biology. -

And Q. Rubra Acorns and in Carya Ovata and C

NEST RECOGNITION IN THE ANT, LEPTOTHORAX AMBIGUUS EMERY (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE)* BY THOMAS M. ALLOWAY AND SANDRA HODGSON Erindale College, University of Toronto, Mississauga, Ontario LSL 1C6, Canada INTRODUCTION Leptothorax ambiguus Emery is a species of minute ants. In southern Ontario, colonies most frequently nest in old Quercus alba and Q. rubra acorns and in Carya ovata and C. cordiformis hickory nuts, which beetle larvae (especially Curculionidae) and other insects have partly hollowed out before the ants move in. L. ambi- guus colonies frequently contain several functional queens (poly- gyny) and often occupy several acorn nests (polydomy). A 'typical' large colony would occupy 2 or 3 acorn nests and consist of 3 or 4 queens, 75 to 100 workers, and a brood of eggs, larvae, and pupae (Alloway et al. 1982). L. ambiguus colonies defend the area around their nests against incursions by workers from other L. ambiguus colonies and from colonies of two closely related species, L. curvispinosus Mayr and L. longispinosus Roger. During territorial battles, workers bite and sting their adversaries and employ tandem running (M6glich et al. 1974) to recruit nestmates to places where workers from the other colony have been encountered (Alloway 1980). The co-occurrence of territoriality and polydomy and the fact that L. ambiguus colo- nies are sometimes raided by the slave-making parasites Lepto- thorax duloticus Wesson or Protomognathus americanus (Emery) led us to wonder whether L. ambiguus colonies possess the capacity to discriminate between one of their own nests and a nest belonging to another L. ambiguus colony. Such an ability should be useful if part of a polydomous colony had to evacuate a nest in which they had been living and emigrate to one of their colony's other nests as a consequence of either a territorial fight, a slave raid, or structural damage to their acorn nest. -

By Thomas M. Alloway,Alfred Buschinger, Mary Talbot,4

POLYGYNY AND POLYDOMY IN THREE NORTH AMERICAN SPECIES OF THE ANT GENUS LEPTOTHORAX MAYR (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE) BY THOMAS M. ALLOWAY, ALFRED BUSCHINGER, MARY TALBOT,4 ROBIN Stuart, AND CYNTHIA THOMAS GENERAL INTRODUCTION This paper deals with certain behavioral and ecological factors which may be relevant to the evolution and maintenance of social parasitism in ants. We will argue that some of the same factors which might predispose one species to evolve into a social parasite might make resistance to parasitism difficult for a closely related species. After their mating flight, the queens of most nonparasitic ant species found new colonies alone. A queen of such a species finds a suitable nesting place, excavates a small cavity, and seals herself inside. She then lays a clutch of eggs and feeds her first larvae a special "baby food" derived metabolically from the degeneration of her wing muscles and fat body. These larvae mature to become female workers which forage for food, enlarge the nest, feed the queen, and rear subsequent broods of workers and reproductives. Mature ant colonies usually occupy only one nest (monodomy). However, the number of queens in typical mature colonies varies. Colonies of some species never contain more than one functional queen (monogyny), while colonies of other species often have multi- ple queens (polygyny) (Buschinger 1974). However, the queens of all known obligatory slave-making, in- quiline, and temporary-parasite species found colonies non-inde- 1. This research was supported by grants to Thomas Alloway from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and to Alfred Buschinger from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. -

Myrmecological News Myrmecologicalnews.Org

Myrmecological News myrmecologicalnews.org Myrmecol. News 30 Digital supplementary material Digital supplementary material to DE LA MORA, A., SANKOVITZ, M. & PURCELL, J. 2020: Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) as host and intruder: recent advances and future directions in the study of exploitative strategies. – Myrmecological News 30: 53-71. The content of this digital supplementary material was subject to the same scientific editorial processing as the article it accompanies. However, the authors are responsible for copyediting and layout. Supporting Material for: de la Mora, Sankovitz, & Purcell. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) as host and intruder: recent advances and future directions in the study of exploitative strategies Table S1: This table summarizes host/parasite relationships that have been described or discussed in the literature since 2000. Host and parasite nomenclature is up‐to‐date based on AntWeb.org, but note that some of the taxonomy is controversial and/or not fully resolved. Names are likely to change further in coming years. Due to changing nomenclature, it can be challenging to track which species have been well‐studied. We provide recently changed species and genus names parenthetically. In addition, we have split this table to show recent taxonomic revisions, compilations (e.g. tables in empirical papers), reviews, books, or species descriptions supporting relationships between hosts and parasites in one column and articles studying characteristics of host/parasite relationships in a second column. For well‐studied species, we limit the ‘primary research’ column to five citations, which are selected to cover different topics and different research teams when such diverse citations exist. Because of the active work on taxonomy in many groups, some misinformation has been inadvertently propagated in previous articles. -

The Maryland Entomologist

THE MARYLAND ENTOMOLOGIST Insect and related-arthropod studies in the Mid-Atlantic region Volume 5, Number 4 September 2012 September 2012 The Maryland Entomologist Volume 5, Number 4 MARYLAND ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY Executive Committee: President Frederick Paras Vice President Philip J. Kean Secretary Richard H. Smith, Jr. Treasurer Edgar A. Cohen, Jr. Publications Editor Eugene J. Scarpulla Historian Robert S. Bryant The Maryland Entomological Society (MES) was founded in November 1971, to promote the science of entomology in all its sub-disciplines; to provide a common meeting venue for professional and amateur entomologists residing in Maryland, the District of Columbia, and nearby areas; to issue a periodical and other publications dealing with entomology; and to facilitate the exchange of ideas and information through its meetings and publications. The MES logo features an illustration of Euphydryas phaëton (Drury), the Baltimore Checkerspot, with its generic name above and its specific epithet below (both in capital letters), all on a pale green field; all these are within a yellow ring double-bordered by red, bearing the message “* Maryland Entomological Society * 1971 *”. All of this is positioned above the Shield of the State of Maryland. In 1973, the Baltimore Checkerspot was named the official insect of the State of Maryland through the efforts of many MES members. Membership in the MES is open to all persons interested in the study of entomology. All members receive the annual journal, The Maryland Entomologist, and the digital e-newsletter, Phaëton. Institutions may subscribe to The Maryland Entomologist but may not become members. Prospective members should send to the Treasurer full dues for the current MES year (October – September), along with their full name, address, telephone number, e-mail address and entomological interests. -

Social Interactions Promote Adaptive Resource Defense in Ants

Erschienen in: PLoS ONE ; 12 (2017), 9. - e0183872 http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183872 RESEARCH ARTICLE Social interactions promote adaptive resource defense in ants Christoph Johannes Kleineidam*, Eva Linda Heeb, Stefanie Neupert Behavioral Neurobiology, Department of Biology, University of Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany * [email protected] a1111111111 Abstract a1111111111 a1111111111 Social insects vigorously defend their nests against con- and heterospecific competitors. a1111111111 Collective defense is also seen at highly profitable food sources. Aggressive responses are a1111111111 elicited or promoted by several means of communication, e.g. alarm pheromones and other chemical markings. In this study, we demonstrate that the social environment and interac- tions among colony members (nestmates) modulates the propensity to engage in aggres- sive behavior and therefore plays an important role in allocating workers to a defense task. OPEN ACCESS We kept Formica rufa workers in groups or isolated for different time spans and then tested Citation: Kleineidam CJ, Heeb EL, Neupert S their aggressiveness in one-on-one encounters with other ants. In groups of more than 20 (2017) Social interactions promote adaptive workers that are freely interacting, individuals are aggressive in one-on-one encounters with resource defense in ants. PLoS ONE 12(9): non-nestmates, whereas aggressiveness of isolated workers decreases with increasing iso- e0183872. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0183872 lation time. We conclude that ants foraging collectively and interacting frequently, e.g. along foraging trails and at profitable food sources, remain in a social context and thereby maintain Editor: James C. Nieh, University of California San Diego, UNITED STATES high aggressiveness against potential competitors. -

Complexity and Behaviour in Leptothorax Ants

Complexity and behaviour in Leptothorax ants Octavio Miramontes Universidad Nacional Aut´onomade M´exico Mexico City Boston Vi¸cosa Madrid Cuernavaca Beijing CopIt ArXives 2007 CopIt ArXives Mexico City Boston Vi¸cosa Madrid Cuernavaca Beijing Copyright 1993 by Octavio Miramontes Published 2007 by CopIt ArXives All property rights of this publications belong to the author who, however, grants his authorization to the reader to copy, print and distribute his work freely, in part or in full, with the sole conditions that (i) the author name and original title be cited at all times, (ii) the text is not modified or mixed and (iii) the final use of the contents of this publication must be non commercial Failure to meet these conditions will be a violation of the law. Electronically produced using Free Software and in accomplishment with an Open Access spirit for academic publications Social behaviour in ants of the genus Leptothorax is reviewed. Attention is paid to the existence of collective robust periodic oscillations in the activity of ants inside the nest. It is known that those oscillations are the outcome of the process of short-distance interactions among ants and that the activity of individual workers is not periodic. Isolated workers can activate spontaneously in a unpredictable fashion. A model of an artificial society of computer automata endowed with the basic behavioural traits of Leptothorax ants is presented and it is demonstrated that collective periodic oscillations in the activity domain can exist as a consequence of interactions among the automata. It is concluded that those oscillations are generic properties common to both natural and artificial social complex systems. -

Population Fluidity in Leptothorax Longispinosus (Hymenoptera:Formicidae)*

POPULATION FLUIDITY IN LEPTOTHORAX LONGISPINOSUS (HYMENOPTERA:FORMICIDAE)* BY JOAN M. HERBERS AND CAROL W. TUCKER Department of Zoology, University of Vermont Burlington VT 05405 INTRODUCTION Although social insect colonies are commonly conceived as stable entities in time and in space, considerable information exists to demonstrate that population fluidity can be pronounced. Data on ants show that workers can be exchanged between nests (Kan- nowski 1959; Scherba 1965; Chauvin and Leconte 1965; Alloway et al 1982; Del Rio Pesado and Alloway 1983; MacKay and MacKay 1983); a colony can undergo budding (Scherba 1958; Talbot 1961; Brian 1965; Cherix et al 1980; Stuart 1985; Pamilo et al. 1985); and entire nests can move from one site to another (Van Pelt 1976; Smallwood and Culver 1979; Smallwood 1982; Droual 1984; Herbers 1985). These observations lead to the conclusion that in some species the colony is not a fixed entity, but rather a shifting collection influenced by ecological contingencies. That a given colony can occupy more than one physical nest site, a condition known as polydomy, deserves particular attention (Fletcher and Ross 1985). Evolutionary dynamics under conditions of colony fractionation are poorly understood, even though the consequences for eusocial evolution may be profound. There is sur- prisingly little information to document and measure the extent of population fluidity for any species, a gap we help to fill in this paper. Recent work demonstrates that some species of leptothoracine ants are polydomous (Alloway et al 1982; Del Rio Pesado and Alloway 1983; Stuart 1985). These inconspicuous temperate species are well-suited for detailed studies of polydomy because they are small and easy to culture. -

Download Special Issue

Psyche Advances in Neotropical Myrmecology Guest Editors: Jacques Hubert Charles Delabie, Fernando Fernández, and Jonathan Majer Advances in Neotropical Myrmecology Psyche Advances in Neotropical Myrmecology Guest Editors: Jacques Hubert Charles Delabie, Fernando Fernandez,´ and Jonathan Majer Copyright © 2012 Hindawi Publishing Corporation. All rights reserved. This is a special issue published in “Psyche.” All articles are open access articles distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Editorial Board Arthur G. Appel, USA John Heraty, USA Mary Rankin, USA Guy Bloch, Israel DavidG.James,USA David Roubik, USA D. Bruce Conn, USA Russell Jurenka, USA Coby Schal, USA G. B. Dunphy, Canada Bethia King, USA James Traniello, USA JayD.Evans,USA Ai-Ping Liang, China Martin H. Villet, South Africa Brian Forschler, USA Robert Matthews, USA William T. Wcislo, Panama Howard S. Ginsberg, USA Donald Mullins, USA DianaE.Wheeler,USA Abraham Hefetz, Israel Subba Reddy Palli, USA Contents Advances in Neotropical Myrmecology, Jacques Hubert Charles Delabie, Fernando Fernandez,´ and Jonathan Majer Volume 2012, Article ID 286273, 3 pages Tatuidris kapasi sp. nov.: A New Armadillo Ant from French Guiana (Formicidae: Agroecomyrmecinae), Sebastien´ Lacau, Sarah Groc, Alain Dejean, Muriel L. de Oliveira, and Jacques H. C. Delabie Volume 2012, Article ID 926089, 6 pages Ants as Indicators in Brazil: A Review with Suggestions