Prelims Nov 2005.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ExperienceTallinn

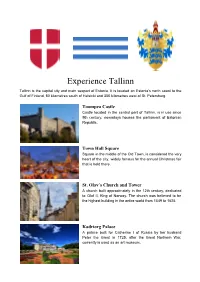

Experience Tallinn Tallinn is the capital city and main seaport of Estonia. It is located on Estonia's north coast to the Gulf of Finland, 80 kilometres south of H elsinki and 350 kilometres w est of S t. P etersburg. Toompea C astle Castle located in the central part of Tallinn, is in use since 9th century, nowadays houses the parliament of Estonian Republic. Town H all Square Square in the middle of the Old Town, is considered the very heart of the city, widely famous for the annual Christmas fair that is held there. St. O lav’s C hurch and T ower A church built approximately in the 12th century, dedicated to Olaf II, King of Norway. The church was believed to be the highest building in the entire w orld from 1549 to 1625. Kadriorg Palace A palace built for Catherine I of Russia by her husband Peter the Great in 1725, after the Great Northern War, currently is used as an art m useum. Town H all Pharmacy A pharmacy located on the Town Hall Square, which has been working continuosly since 14th century. Even nowadays one can buy any medicin needed from the pharmacy. Contains a little exhibition of different items used to treat diseases in the M iddle ages. St. A lexander N evsky C athedral The large and richly decorated Russian Orthodox church, designed in a mixed historicist style, was completed on Toompea Hill in 1900, when Estonia was part of the Czarist Empire. -

Russian Art, Icons + Antiques

RUSSIAN ART, ICONS + ANTIQUES International auction 872 1401 - 1580 RUSSIAN ART, ICONS + ANTIQUES Including The Commercial Attaché Richard Zeiner-Henriksen Russian Collection International auction 872 AUCTION Friday 9 June 2017, 2 pm PREVIEW Wednesday 24 May 3 pm - 6 pm Thursday 25 May Public Holiday Friday 26 May 11 am - 5 pm Saturday 27 May 11 am - 4 pm Sunday 28 May 11 am - 4 pm Monday 29 May 11 am - 5 pm or by appointment Bredgade 33 · DK-1260 Copenhagen K · Tel +45 8818 1111 · Fax +45 8818 1112 [email protected] · bruun-rasmussen.com 872_russisk_s001-188.indd 1 28/04/17 16.28 Коллекция коммерческого атташе Ричарда Зейнера-Хенриксена и другие русские шедевры В течение 19 века Россия переживала стремительную трансформацию - бушевала индустриализация, модернизировалось сельское хозяйство, расширялась инфраструктура и создавалась обширная телеграфная система. Это представило новые возможности для международных деловых отношений, и известные компании, такие как датская Бурмэйстер энд Вэйн (В&W), Восточно-Азиатская Компания (EAC) и Компания Грэйт Норсерн Телеграф (GNT) открыли офисы в России и внесли свой вклад в развитие страны. Большое количество скандинавов выехало на Восток в поисках своей удачи в растущей деловой жизни и промышленности России. Среди многочисленных путешественников возникало сильное увлечение культурой страны, что привело к созданию высококачественных коллекций русского искусства. Именно по этой причине сегодня в Скандинавии так много предметов русского антиквариата, некоторые из которых будут выставлены на этом аукционе. Самые значимые из них будут ещё до аукциона выставлены в посольстве Дании в Лондоне во время «Недели Русского Искусства». Для более подробной информации смотри страницу 9. Изюминкой аукциона, без сомнения, станет Русская коллекция Ричарда Зейнера-Хенриксена, норвежского коммерческого атташе. -

TSARINA Ellen Alpsten

Book Club Guide TSARINA Ellen Alpsten In brief Lover, murder, mother, Tsarina. Memoirs of a Geisha meets Game of Thrones in this page-turning epic charting the extraordinary rags-to-riches tale of the most powerful woman history ever forgot. In detail Spring 1699: Illegitimate, destitute and strikingly beautiful, Marta has survived the brutal Russian winter in her remote Baltic village. Sold by her family into household labour at the age of fifteen, Marta survives by committing a crime that will force her to go on the run. A world away, Russia's young ruler, Tsar Peter I, passionate and iron-willed, has a vision for transforming the traditionalist Tsardom of Russia into a modern, Western empire. Countless lives will be lost in the process. Falling prey to the Great Northern War, Marta cheats death at every turn, finding work as a washerwoman at a battle camp. One night at a celebration, she encounters Peter the Great. Relying on her wits and her formidable courage, and fuelled by ambition, desire and the sheer will to live, Marta will become Catherine I of Russia. But her rise to the top is ridden with peril; how long will she survive the machinations of Peter's court, and more importantly, Peter himself? Author Biography Ellen Alpsten was raised in Kenya. She won the Grande École short story competition for her novella Meeting Mr Gandhi while studying for her Msc in PPE, and went on to work as a producer and presenter for Bloomberg TV in London. She has written for Vogue and Conde Nast Traveller. -

RUSSIAN ART, ICONS + ANTIQUES Including the Commercial Attaché Richard Zeiner-Henriksen Russian Collection

RUSSIAN ART, ICONS + ANTIQUES Including The Commercial Attaché Richard Zeiner-Henriksen Russian Collection International auction 872 AUCTION Friday 9 June 2017, 2 pm PREVIEW Wednesday 24 May 3 pm - 6 pm Thursday 25 May Public Holiday Friday 26 May 11 am - 5 pm Saturday 27 May 11 am - 4 pm Sunday 28 May 11 am - 4 pm Monday 29 May 11 am - 5 pm or by appointment Bredgade 33 · DK-1260 Copenhagen K · Tel +45 8818 1111 · Fax +45 8818 1112 [email protected] · bruun-rasmussen.com 872_russisk_s001-188.indd 1 28/04/17 16.28 Коллекция коммерческого атташе Ричарда Зейнера-Хенриксена и другие русские шедевры В течение 19 века Россия переживала стремительную трансформацию - бушевала индустриализация, модернизировалось сельское хозяйство, расширялась инфраструктура и создавалась обширная телеграфная система. Это представило новые возможности для международных деловых отношений, и известные компании, такие как датская Бурмэйстер энд Вэйн (В&W), Восточно-Азиатская Компания (EAC) и Компания Грэйт Норсерн Телеграф (GNT) открыли офисы в России и внесли свой вклад в развитие страны. Большое количество скандинавов выехало на Восток в поисках своей удачи в растущей деловой жизни и промышленности России. Среди многочисленных путешественников возникало сильное увлечение культурой страны, что привело к созданию высококачественных коллекций русского искусства. Именно по этой причине сегодня в Скандинавии так много предметов русского антиквариата, некоторые из которых будут выставлены на этом аукционе. Самые значимые из них будут ещё до аукциона выставлены в посольстве Дании в Лондоне во время «Недели Русского Искусства». Для более подробной информации смотри страницу 9. Изюминкой аукциона, без сомнения, станет Русская коллекция Ричарда Зейнера-Хенриксена, норвежского коммерческого атташе. Мы представляем эту коллекцию в сотрудничестве с норвежским аукционным домом Бломквист (Blomqvist Kunsthandel AS) в Осло. -

Edinburgh University Library Handlist of Manuscripts

H21 The Dashkov medals Reference Code GB 237 Coll-21 Shelfmark or location Medals No. 119 In 1777 Princess Ekaterina Romanovna Vorontsova Dashkova arrived in Scotland with her son Paul (Pavel Mikhailovich Dashkov). Her son immediately began studies at Edinburgh University, and in 1779 the Princess, still resident in Edinburgh, gave a collection of Russian commemorative medals to mark the occasion of the graduation of Paul as a Master of Arts. The medals, over 150 in number and all made of copper, were entrusted first to Professor John Robison, Professor of Natural Philosophy in the University and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, who was instructed to make a catalogue of them. In the early 1770s, Robison had very briefly held the Chair of Mathematics in the Imperial Naval Cadet Corps at Kronstadt, where he had been given the rank of Colonel. The medals were only handed back to the University after Robison's death in 1805. If a catalogue was ever made by Robison it did not survive, and a proper catalogue of the collection still has to be compiled. Some of the medals show rulers of Russia, military figures, statesmen, events of the reign of Peter the Great. Others mark events such as coronations, accessions, marriages and deaths of Russian rulers. Imperial institutions are commemorated, as are cities and buildings of the Russian empire. Dashkova Medals: interim list Number Short title Description Diameter (mm) Material Notes DM/1 Andrei Alexandrovich Andrei Alexandrovich (1281-1304). 39 mm copper Language: Russian Obverse: bust of Dimitri Ivanovich. Reverse: Russian inscription. -

K (^Oetutl^ J^Tsir N P2MSE P©B EYERYB©BY

! ^ STOM FEHT01ES k (^OetUtl^ j^tSir n P2MSE P©B EYERYB©BY ©ggjsiir Hsis si Swnffit MMifQiMdDininal !D)n§si[iP[p©ninittiniii©niitt On the Spur of 1 1 1 P.M- 1:30 ftwl 6 P-M the Moment '' BY ROY MOULTON. I DPP VSORRV, »l)T WE HAVE TO ANSWER G*7ouT) /A^l^^OeT^HARRlCD' Written Exclusively for Evening St»f. CD A j /b^ BRST I Hw/tcToet (CLOSE OP NOW, SIR. BY \ WILL WAY *S\R, VOO ARE THE t ( MY TROUSSSAU. Yo3 THE VIChTvANtS*ToAGCTFMA»»!lo -t ALONG ANO HELP /( THIRD -16NTLEMAN WHO HAs I'TIOM TUB IIICKUYVH.I* ci.ah.iox V Sg«T WAY. 1I AM ?i,«aleSL A (OO V J I He SELECT IT? S WAITED fW THAT SAME LADY, Blmer Jones Is dickerin’ with a fe<* j ^- °°MC SACK. ler for a plug hat and there la somn i \ HER/I^ V_J° tuik that he is goin’ into the under* takin’ business. O——O Ami- Hilliker traded off bis cheese an oatmobile and the next, V • factory for V day the oatmobile blowed up. Arne says there are times in a feller’s life when he cnn’t lay up a. cent, O-O The only thing on this earth that will stick closer than a brother Is the screw top on a glass fruit ,1ar. o—o There is several ways to eat sauer- kraut. but the best way is by proxy. O-O f never yit see a woman who would admit that she had anything to wear, and judgin’ by the statues in the mu, soums, I guess In the old days they really didn’t. -

Catherinethegreat.Pdf

First Published 2004 Indian Council of Philosophical Research Published by: INDIAN COUNCIL OF PHILOSOPHICAL RESEARCH Darshan Bhawan 36, Tughlakabad Institutional Area Mehrauli Badarpur Road New Delhi 110062 © Indian Council of Philosophical Research (ICPR) ISBN 81-85636-85-0 Catherine the Great Acknowledgements This monograph is part of a series on Value-oriented Education centered on three values: Illumination, Heroism and Harmony. The research, preparation and publication of the monographs that form part of this series are the result of the cooperation of the fol lowing members of the research team of the Sri Aurobindo Inter national Institute of Educational Research, Auroville: Abha, Alain, Anne, Ashatit, Auralee, Bhavana, Christine, Claude, Deepti, Don, Frederick, Ganga, Jay Singh, Jean-Yves, Jossi, Jyoti Madhok, Kireet Joshi, Krishna, Lala, Lola, Mala, Martin, Mirajyoti, Namrita, Olivier, Pala, Pierre, Serge, Shailaja, Shan karan, Sharanam, Soham, Suzie, Varadharajan, Vladimir, Vigyan. General Editor: KIREET JOSHI Author of this monograph: Ashatit We are grateful to many individuals in and outside Auroville who, besides the above mentioned researchers and general editor, have introduced us to various essays which are included in full or in parts in this experimental compilation. Our special thanks to Veronique Nicolet (Auroville) for her paint ing which we reproduced on the cover as well as in the preface. Cover design: Serge Brelin, Auroville Press Publishers The Indian Council of Philosophical Research (ICPR) acknowl edges with gratefulness the labor of research and editing of the team of researchers of the Sri Aurobindo International Institute of Educational Research, Auroville. Printed in Auroville Press, 2004 Illumination, Heroism and Harmony Catherine the Great General Editor: KIREET JOSHI · Illumination, Heroism and Harmony Preface The task of preparing teaching-learning material for value-ori ented education is enormous. -

Catherine the Great Free

FREE CATHERINE THE GREAT PDF Robert K. Massie | 656 pages | 14 Jul 2016 | Head of Zeus | 9781784975845 | English | London, United Kingdom Catherine the Great: Official Website for the Series | HBO Catherine the Great May 2, —Nov. She expanded Russia's borders to the Black Sea and into central Europe during her reign. She also promoted westernization and modernization for her country, though it was within the context of maintaining her autocratic control over Russia and increasing the power of the landed gentry over the serfs. She was known as Frederike or Fredericka. As was common for royal and noblewomen, she was educated at home by tutors. She learned French and German and also studied history, music, and the religion of her homeland, Lutheranism. Elizabeth, unmarried and childless, had named Peter as her heir to the Russian throne. Peter, though the Romanov heir, was a German prince. Peter the Great had 14 children by his two wives, only three of whom survived to adulthood. His son Alexei died in prison, convicted of plotting to overthrow his father. Anna had died in following the birth of her only son, a Catherine the Great years Catherine the Great her father died and while her mother Catherine I of Russia ruled. Though Catherine had the support of Peter's mother, the Empress Elizabeth, she disliked her husband—Catherine later wrote she Catherine the Great been more interested in the crown than the person—and first Peter and then Catherine were unfaithful. Her first son Paul later emperor or czar of Russia as Paul I, was Catherine the Great nine years into the marriage, Catherine the Great some question whether his father was Catherine's husband. -

13 – the KITCHEN STAIRCASE the Stairs Were Constructed by the Team

№ 13 – THE KITCHEN STAIRCASE The stairs were constructed by the team of carpenters led by Johann Baptist Eger in 1740. The staircase was dismantled in 1939 to make a ceiling between the ground and first floors. Reconstruction of the staircase was carried out from photos (woodcarver V. Rape, St. Petersburg). Opened to the public in 1981. • Console - table. Germany. Early 18th c. • Vase. China. 18th c., (with a brass mount, made in Europe). • Mirror. Russia. 19th c. • Unknown artist. Settlement Near the Ford. Holland. 2nd half of the 17th c. • Unknown artist. Abraham’s Sacrifice. Late 18th c. • Unknown artist, Flemish school. Spanish Cavalryman. 17th c. • Unknown artist, Flemish school. Spanish Cavalryman. 17th c. • Latern. A copy from the18th century lantern in the Kuskovo Palace, Moscow. • Console – table (on the ground floor). A copy from the 18th century original. • Bust of A. (?) Lassie. Latvia. 2nd half of the 18th c. • Wallsconces. Copies after the 18th century pattern. № 70 – THE ANTECHAMBER OF THE GOLD HALL From the original appearance of the palace the stucco ceiling made by Johann Michael Graff in the 1760s, the parquet and the door to the Gold Hall have survived. The stove after the original Rundāle stoves was made in a workshop in St. Petersburg. The brocatelle wall hangings were woven in Moscow. The objects d’art exhibited in the rooms do not belong to the original arrangement, because in 1795 Duke Peter took the inventory from the palaces of Courland to Sagan Castle in Silesia. 1. Cartel clock. France. Godo (Godeau à Chateaudun). 2nd half of the 18th c. -

I Fall 2019 I

BOOKS I FALL 2019 I I 38° 54' 19" N I 77° 02’ 13” W I * NationalGeographic.com/Books NatGeoBooks @NatGeoBooks * IF YOU’REYOU’RE WONDERING, WONDERING, THESE THESE ARE THE ARE COORDINATES THE COORDINATES OF OF HUBBARDHUBBARD HALL HALL AT AT NATIONAL NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC GEOGRAPHIC HEADQUARTERS HEADQUARTERS NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC PARTNERS LLC, a joint venture between National Geographic Society National Geographic Books are distributed to the trade by Penguin Random House. and 21st Century Fox, combines National Geographic television channels with National Geographic’s media For ordering information, or to contact your local sales representative, please call or write: and consumer-oriented assets, including National Geographic magazines; National Geographic Studios; related digital and social media platforms; books; maps; children’s media; and ancillary activities that include UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL SCHOOLS & LIBRARIES travel, global experiences and events, archival sales, catalog, licensing and e-commerce businesses. Penguin Random House Customer Service (except United Kingdom) Librarians and other educators can request 400 Hahn Road Penguin Random House, Inc. our latest catalog for School & Public Westminster, MD 21157 International Department Libraries by calling 1-877-873-6846. A portion of the proceeds from National Geographic Partners LLC will be used to fund science, exploration, 1745 Broadway Visit www.nationalgeographic.com/books conservation and education through significant ongoing contributions to the work of the To order by phone or for customer service: New York, NY 10019 National Geographic books are also 1-800-733-3000 1-212-829-6712 available through your regular wholesaler. National Geographic Society. Available daily Fax: 1-212-572-6045; 8:30 AM to 5:00 PM EST 1-212-829-6700 Catalog entries list the suggested cover (Eastern and Central Accounts) Email: [email protected] price. -

Cahiers Du Monde Russe, 52\/1

Cahiers du monde russe Russie - Empire russe - Union soviétique et États indépendants 52/1 | 2011 Varia For love and fatherland : Political clientage and the Origins of Russia’s first female order of chivalry Pour l’amour et la patrie : le clientélisme politique et les origines du premier ordre russe de chevalerie pour les femmes Igor Fedyukin et Ernest A. Zitser Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/monderusse/9320 DOI : 10.4000/monderusse.9320 ISSN : 1777-5388 Éditeur Éditions de l’EHESS Édition imprimée Date de publication : 5 mars 2011 Pagination : 5-44 ISBN : 978-2-7132-2351-8 ISSN : 1252-6576 Référence électronique Igor Fedyukin et Ernest A. Zitser, « For love and fatherland : Political clientage and the Origins of Russia’s first female order of chivalry », Cahiers du monde russe [En ligne], 52/1 | 2011, mis en ligne le 28 mars 2014, Consulté le 22 avril 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/monderusse/9320 ; DOI : 10.4000/monderusse.9320 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 22 avril 2019. © École des hautes études en sciences sociales For love and fatherland : Political clientage and the Origins of Russia’s fir... 1 For love and fatherland : Political clientage and the Origins of Russia’s first female order of chivalry Pour l’amour et la patrie : le clientélisme politique et les origines du premier ordre russe de chevalerie pour les femmes Igor Fedyukin et Ernest A. Zitser NOTE DE L'AUTEUR The authors wish to thank Gary Marker (SUN Y-Stony Brook), the anonymous reviewers at the Cahiers, as well as the organizers and participants of the seminars held at the European University in St. -

Journey Text and Recorded History Migration Of

THE JOURNEY OF MAN MODERN HOMO SAPIENS ARE TRACED TO ABOUT 60,000 YEARS AGO AND MIGRATORY PATHS PROVEN IN 2002 BY A GROUP OF AMERICAN GENETICISTS AND SCIENTISTS LED BY DR. SPENCER WELLS OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY MADE PUBLIC A TEN YEAR RESEARCH PROJECT. THEY FOLLOWED THE MALE “Y” CHROMOSOME AND THE GENETIC MARKERS IN NUCLEAR DNA TO TRACE THE CRADLE OF MANKIND TO CENTRAL AFRICA AND THE VILLAGE OF SAN WHICH IS NEAR RUNDU, NAMIBIA AND CONFIRMING THE “OUT OF AFRICA HYPOTHESIS”. ANOTHER GROUP OF 55,000 SANS PEOPLE PRESENTLY LIVING ALSO RESIDE IN BOTSWANA. TWO THOUSAND GENERATIONS BACK OR APPROXIMATELY 50,000 YEARS AGO THEY DISCOVERED THE DECENDENTS OF THE OLDEST TRIBE IN AFRICA AND THE BEGINNING OF MODERN MAN BASED ON COLLECTED NUCLEAR DNA AND GENETIC MARKERS FROM THOUSANDS OF BLOOD SAMPLES FROM POPULATIONS AROUND THE WORLD. SOME OF THESE SAME PEOPLE ‘SANS BUSHMEN’ WITH A POPULATION AT THAT TIME OF ABOUT 10,000 TOTAL AND THEIR DECENDENTS MOVED 1200 MILES SOUTH AND EAST IN AFRICA AND THEN PROCEED TO FOLLOW THE COASTLINE NORTH AND EASTWARD TO INDIA AND THEN ON DOWN THE COASTLINES TO SOUTHEAST ASIA TO AUSTRALIA. THEY VERIFIED ONE OF THE OLDEST SETTLEMENTS ON THE WEST SIDE OF MADERAI, INDIA ABOUT 200 MILES NORTH OF THE COASTLINE TO MATCH THE “Y” CHROMOSOME OF THE CENTRAL AFRICANS AND A VERIFICATION WAS ALSO PROVIDED ON THE AUSTRALIAN MONGO ABORIGINE PEOPLE DNA TO BE ON A TIMELINE ABOUT 10,000 YEARS AFTER THE CENTRAL AFRICANS. ANOTHER MIGRATION WAS HAPPENING ABOUT 35,000 YEARS AGO THAT PLACES THE DNA GENETIC MARKER TO THE MIDDLE EAST WHERE IT SPLITS AND SOME GO SOUTH TO INDIA AND SOME CONTINUE TO MOVE NORTHEAST TO KAZIKSTAN WHERE THEY FIND THE OLDEST LINEAGES IN CENTRAL ASIA.