Queens (Online Appendix)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prelims Nov 2005.Qxd

German Historical Institute London Bulletin Bd. 27 2005 Nr. 2 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Stiftung Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. CLARISSA CAMPBELL ORR (ed.), Queenship in Europe 1660–1815: The Role of the Consort (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), xvii + 419 pp. ISBN 0 521 81422 7. £60.00 ($100.00) During the past decade the literature on women at the European courts has grown rapidly. Queenship in Europe 1660–1815 is a wel- come addition to this expanding field of research and it appears as a natural extension of Clarissa Campbell Orr’s previous volume enti- tled Queenship in Britain, 1660–1837 (2002). Queenship in Europe consists of a fine introduction by the editor and fourteen essays on various consorts and/or mistresses. After a brief overview of the volume, this review will focus on Campell Orr’s introduction and a few selected papers that exemplify the strengths of the collection and reveal some of the difficulties that arise when court history is combined with gender history. In the first essay, Robert Oresko traces the life of the powerful Maria Giovanna Battista of Savoy-Nemours (1644–1724) with an emphasis on her regency and her extensive building projects. -

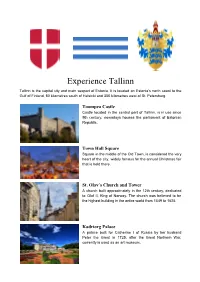

ExperienceTallinn

Experience Tallinn Tallinn is the capital city and main seaport of Estonia. It is located on Estonia's north coast to the Gulf of Finland, 80 kilometres south of H elsinki and 350 kilometres w est of S t. P etersburg. Toompea C astle Castle located in the central part of Tallinn, is in use since 9th century, nowadays houses the parliament of Estonian Republic. Town H all Square Square in the middle of the Old Town, is considered the very heart of the city, widely famous for the annual Christmas fair that is held there. St. O lav’s C hurch and T ower A church built approximately in the 12th century, dedicated to Olaf II, King of Norway. The church was believed to be the highest building in the entire w orld from 1549 to 1625. Kadriorg Palace A palace built for Catherine I of Russia by her husband Peter the Great in 1725, after the Great Northern War, currently is used as an art m useum. Town H all Pharmacy A pharmacy located on the Town Hall Square, which has been working continuosly since 14th century. Even nowadays one can buy any medicin needed from the pharmacy. Contains a little exhibition of different items used to treat diseases in the M iddle ages. St. A lexander N evsky C athedral The large and richly decorated Russian Orthodox church, designed in a mixed historicist style, was completed on Toompea Hill in 1900, when Estonia was part of the Czarist Empire. -

Press Kit Lille 2016

www.lilletourism.com PRESS KIT LILLE 2016 ALL YOU NEED IS LILLE Press Release Just 80 minutes away from London, 1 hour from Paris and 35 minutes from Brussels, Lille could quite easily have melted into the shadows of its illustrious neighbours, but instead it is more than happy to cultivate and show off all that makes it stand out from the crowd! Flemish, Burgundian and then Spanish before it became French, Lille boasts a spectacular heritage. A trading town since the Middle Ages, a stronghold under Louis XIV, a hive of industry in the 19th century and an ambitious hub in the 20th century, Lille is now imbued with the memories of the past, interweaved with its visions for the future. While the Euralille area is a focal point of bold architecture by Rem Koolhaas, Jean Nouvel or Christian de Portzamparc, the Lille-Sud area is becoming a Mecca for fashionistas. Since 2007, some young fashion designers (sponsored by Agnès b.) have set up workshops and boutiques in this new “fashion district” in the making. With lille3000, it’s the whole city that has started to look towards the future, enjoying a dramatic makeover for this new recurrent event, geared towards contemporary art and innovation. The European Capital of Culture in 2004, Lille is now a leading light in this field, with the arts ma- king themselves quite at home here. From great museums to new alternative art centres, from the Opera to the theatres through the National Or- chestra, culture is a living and breathing part of everyday life here. -

Russian Art, Icons + Antiques

RUSSIAN ART, ICONS + ANTIQUES International auction 872 1401 - 1580 RUSSIAN ART, ICONS + ANTIQUES Including The Commercial Attaché Richard Zeiner-Henriksen Russian Collection International auction 872 AUCTION Friday 9 June 2017, 2 pm PREVIEW Wednesday 24 May 3 pm - 6 pm Thursday 25 May Public Holiday Friday 26 May 11 am - 5 pm Saturday 27 May 11 am - 4 pm Sunday 28 May 11 am - 4 pm Monday 29 May 11 am - 5 pm or by appointment Bredgade 33 · DK-1260 Copenhagen K · Tel +45 8818 1111 · Fax +45 8818 1112 [email protected] · bruun-rasmussen.com 872_russisk_s001-188.indd 1 28/04/17 16.28 Коллекция коммерческого атташе Ричарда Зейнера-Хенриксена и другие русские шедевры В течение 19 века Россия переживала стремительную трансформацию - бушевала индустриализация, модернизировалось сельское хозяйство, расширялась инфраструктура и создавалась обширная телеграфная система. Это представило новые возможности для международных деловых отношений, и известные компании, такие как датская Бурмэйстер энд Вэйн (В&W), Восточно-Азиатская Компания (EAC) и Компания Грэйт Норсерн Телеграф (GNT) открыли офисы в России и внесли свой вклад в развитие страны. Большое количество скандинавов выехало на Восток в поисках своей удачи в растущей деловой жизни и промышленности России. Среди многочисленных путешественников возникало сильное увлечение культурой страны, что привело к созданию высококачественных коллекций русского искусства. Именно по этой причине сегодня в Скандинавии так много предметов русского антиквариата, некоторые из которых будут выставлены на этом аукционе. Самые значимые из них будут ещё до аукциона выставлены в посольстве Дании в Лондоне во время «Недели Русского Искусства». Для более подробной информации смотри страницу 9. Изюминкой аукциона, без сомнения, станет Русская коллекция Ричарда Зейнера-Хенриксена, норвежского коммерческого атташе. -

TSARINA Ellen Alpsten

Book Club Guide TSARINA Ellen Alpsten In brief Lover, murder, mother, Tsarina. Memoirs of a Geisha meets Game of Thrones in this page-turning epic charting the extraordinary rags-to-riches tale of the most powerful woman history ever forgot. In detail Spring 1699: Illegitimate, destitute and strikingly beautiful, Marta has survived the brutal Russian winter in her remote Baltic village. Sold by her family into household labour at the age of fifteen, Marta survives by committing a crime that will force her to go on the run. A world away, Russia's young ruler, Tsar Peter I, passionate and iron-willed, has a vision for transforming the traditionalist Tsardom of Russia into a modern, Western empire. Countless lives will be lost in the process. Falling prey to the Great Northern War, Marta cheats death at every turn, finding work as a washerwoman at a battle camp. One night at a celebration, she encounters Peter the Great. Relying on her wits and her formidable courage, and fuelled by ambition, desire and the sheer will to live, Marta will become Catherine I of Russia. But her rise to the top is ridden with peril; how long will she survive the machinations of Peter's court, and more importantly, Peter himself? Author Biography Ellen Alpsten was raised in Kenya. She won the Grande École short story competition for her novella Meeting Mr Gandhi while studying for her Msc in PPE, and went on to work as a producer and presenter for Bloomberg TV in London. She has written for Vogue and Conde Nast Traveller. -

RUSSIAN ART, ICONS + ANTIQUES Including the Commercial Attaché Richard Zeiner-Henriksen Russian Collection

RUSSIAN ART, ICONS + ANTIQUES Including The Commercial Attaché Richard Zeiner-Henriksen Russian Collection International auction 872 AUCTION Friday 9 June 2017, 2 pm PREVIEW Wednesday 24 May 3 pm - 6 pm Thursday 25 May Public Holiday Friday 26 May 11 am - 5 pm Saturday 27 May 11 am - 4 pm Sunday 28 May 11 am - 4 pm Monday 29 May 11 am - 5 pm or by appointment Bredgade 33 · DK-1260 Copenhagen K · Tel +45 8818 1111 · Fax +45 8818 1112 [email protected] · bruun-rasmussen.com 872_russisk_s001-188.indd 1 28/04/17 16.28 Коллекция коммерческого атташе Ричарда Зейнера-Хенриксена и другие русские шедевры В течение 19 века Россия переживала стремительную трансформацию - бушевала индустриализация, модернизировалось сельское хозяйство, расширялась инфраструктура и создавалась обширная телеграфная система. Это представило новые возможности для международных деловых отношений, и известные компании, такие как датская Бурмэйстер энд Вэйн (В&W), Восточно-Азиатская Компания (EAC) и Компания Грэйт Норсерн Телеграф (GNT) открыли офисы в России и внесли свой вклад в развитие страны. Большое количество скандинавов выехало на Восток в поисках своей удачи в растущей деловой жизни и промышленности России. Среди многочисленных путешественников возникало сильное увлечение культурой страны, что привело к созданию высококачественных коллекций русского искусства. Именно по этой причине сегодня в Скандинавии так много предметов русского антиквариата, некоторые из которых будут выставлены на этом аукционе. Самые значимые из них будут ещё до аукциона выставлены в посольстве Дании в Лондоне во время «Недели Русского Искусства». Для более подробной информации смотри страницу 9. Изюминкой аукциона, без сомнения, станет Русская коллекция Ричарда Зейнера-Хенриксена, норвежского коммерческого атташе. Мы представляем эту коллекцию в сотрудничестве с норвежским аукционным домом Бломквист (Blomqvist Kunsthandel AS) в Осло. -

Edinburgh University Library Handlist of Manuscripts

H21 The Dashkov medals Reference Code GB 237 Coll-21 Shelfmark or location Medals No. 119 In 1777 Princess Ekaterina Romanovna Vorontsova Dashkova arrived in Scotland with her son Paul (Pavel Mikhailovich Dashkov). Her son immediately began studies at Edinburgh University, and in 1779 the Princess, still resident in Edinburgh, gave a collection of Russian commemorative medals to mark the occasion of the graduation of Paul as a Master of Arts. The medals, over 150 in number and all made of copper, were entrusted first to Professor John Robison, Professor of Natural Philosophy in the University and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, who was instructed to make a catalogue of them. In the early 1770s, Robison had very briefly held the Chair of Mathematics in the Imperial Naval Cadet Corps at Kronstadt, where he had been given the rank of Colonel. The medals were only handed back to the University after Robison's death in 1805. If a catalogue was ever made by Robison it did not survive, and a proper catalogue of the collection still has to be compiled. Some of the medals show rulers of Russia, military figures, statesmen, events of the reign of Peter the Great. Others mark events such as coronations, accessions, marriages and deaths of Russian rulers. Imperial institutions are commemorated, as are cities and buildings of the Russian empire. Dashkova Medals: interim list Number Short title Description Diameter (mm) Material Notes DM/1 Andrei Alexandrovich Andrei Alexandrovich (1281-1304). 39 mm copper Language: Russian Obverse: bust of Dimitri Ivanovich. Reverse: Russian inscription. -

Engravings, Etchings, Mezzotinits, Lithographs, and Acquatints, M0871

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8fr010j No online items Guide to the Leon Kolb collection of Portraits: engravings, etchings, mezzotinits, lithographs, and acquatints, M0871 Finding aid prepared by Finding aid prepared by Processed by Special Collections staff. Stanford University. Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford University Libraries 557 Escondido Mall Stanford, California, 94305-6064 Repository email: [email protected] 2010-09-16 M0871 1 Title: Leon Kolb, collector. Portraits: engravings, etchings, mezzotinits, lithographs, and acquatints Identifier/Call Number: M0871 Contributing Institution: Stanford University. Department of Special Collections and University Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 9.0 Linear feet Date (inclusive): ca. 1600-1800 Abstract: The subjects include rulers, statesmen, authors, scholars and other famous personages from ancient times to the nineteenth century. Most of the prints were produced in the 17th and 18th centuries from paintings by Has Holbein, Anthony Vandyke, Godfrey Kneller, Peter Lely and other noted artists. Processing Information Note Item level description for items in Series 1 was taken from printed catalogue: Portraits: a catalog of the engravings, etchings, mezzotints, and lithographs presented to the Stanford University Library by Dr. and Mrs. Leon Kolb . Compiled by Lenkey, Susan V., [Stanford, Calif.] Stanford University, 1972. Collection Scope and Content Summary Arranged by name of subject, each print in Series 1 is numbered for convenient reference in the various indices in the printed catalogue by Susan Lenkey. Painters and engravers, printing techniques and social and historical positions of the subjects are identified and indexed as well.The subjects include rulers, statesmen, authors, scholars and other famous personages from ancient times to the nineteenth century. -

The Great European Treaties of the Nineteenth Century

JBRART Of 9AN DIEGO OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY EDITED BY SIR AUGUSTUS OAKES, CB. LATELY OF THE FOREIGN OFFICE AND R. B. MOWAT, M.A. FELLOW AND ASSISTANT TUTOR OF CORPUS CHRISTI COLLEGE, OXFORD WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY SIR H. ERLE RICHARDS K. C.S.I., K.C., B.C.L., M.A. FELLOW OF ALL SOULS COLLEGE AWD CHICHELE PROFESSOR OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND DIPLOMACY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD ASSOCIATE OF THE INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS AMEN HOUSE, E.C. 4 LONDON EDINBURGH GLASGOW LEIPZIG NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE CAPETOWN BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS SHANGHAI HUMPHREY MILFORD PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY Impression of 1930 First edition, 1918 Printed in Great Britain INTRODUCTION IT is now generally accepted that the substantial basis on which International Law rests is the usage and practice of nations. And this makes it of the first importance that the facts from which that usage and practice are to be deduced should be correctly appre- ciated, and in particular that the great treaties which have regulated the status and territorial rights of nations should be studied from the point of view of history and international law. It is the object of this book to present materials for that study in an accessible form. The scope of the book is limited, and wisely limited, to treaties between the nations of Europe, and to treaties between those nations from 1815 onwards. To include all treaties affecting all nations would require volumes nor is it for the many ; necessary, purpose of obtaining a sufficient insight into the history and usage of European States on such matters as those to which these treaties relate, to go further back than the settlement which resulted from the Napoleonic wars. -

Josã© Antonio Ulloa Collection of Cartes De Visite

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8g44wcf No online items José Antonio Ulloa collection of cartes de visite Finding aid prepared by Carlota Ramirez, Student Processing Assistant. Special Collections & University Archives The UCR Library P.O. Box 5900 University of California Riverside, California 92517-5900 Phone: 951-827-3233 Fax: 951-827-4673 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.ucr.edu/libraries/special-collections-university-archives © 2017 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. José Antonio Ulloa collection of MS 027 1 cartes de visite Descriptive Summary Title: José Antonio Ulloa collection of cartes de visite Date (inclusive): circa 1858-1868 Collection Number: MS 027 Creator: Ulloa, José Antonio Extent: 0.79 linear feet(2 boxes) Repository: Rivera Library. Special Collections Department. Riverside, CA 92517-5900 Abstract: This collection consists of 60 cartes de visite, owned by José Antonio Ulloa of Zacatecas, Mexico. Items in the collection include photographs and portraits of European, South American, and Central American royalty and military members from the 19th century. Many of the cartes de visite depict members of European royalty related to Napoleon I, as well as cartes de visite of figures surrounding the trial and execution of Mexican Emperor Maximilian I in 1867. Languages: The collection is mostly in Spanish, with some captions in French and English. Access The collection is open for research. Publication Rights Copyright Unknown: Some materials in these collections may be protected by the U.S. Copyright Law (Title 17, U.S.C.). In addition, the reproduction, and/or commercial use, of some materials may be restricted by gift or purchase agreements, donor restrictions, privacy and publicity rights, licensing agreement(s), and/or trademark rights. -

Terrorism Illuminati

t er r o r ism AN D T H E Illu m in at i a t h r ee t h o u sa n d yea r h ist o r y by d av id Liv in g sto n e TERRORISM AND THE ILLUMINATI TERRORISM AND THE ILLUMINATI A Three Thousand Year HISTORy DAVID LIVINGSTONE BOOKSURGE LLC TERRORISM AND THE ILLUMINATI A Three Thousand Year History All Rights Reserved © 2007 by David Livingstone No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. BookSurge LLC For information address: BookSurge LLC An Amazon.com company 7290 B Investment Drive Charleston, SC 29418 www.booksurge.com ISBN: 1-4196-6125-6 Printed in the United States of America And among mankind there is he whose talk “ about the life of this world will impress you, and he calls “ on God as a witness to what is in his heart. Yet, he is the most stringent of opponents. The Holy Koran, chapter 2: 204 If the American people knew what we have done, “ “ they would string us up from the lamp posts. George H.W. Bush Table of Contents Introduction: The Clash of Civilizations 1 Chapter 1: The Lost Tribes The Luciferian Bloodline 7 The Fallen Angels 8 The Medes 11 The Scythians 13 Chapter 2: The Kabbalah Zionism 15 The Chaldean Magi 16 Ancient Greece 17 Plato 19 Alexander 22 Chapter 3: Mithraism Cappadocia 25 The Mithraic Bloodline 28 The Jewish Revolt 32 The Mysteries of Mithras 33 Chapter 4: Gnosticism Herod the Great 37 Paul the Gnostic -

K (^Oetutl^ J^Tsir N P2MSE P©B EYERYB©BY

! ^ STOM FEHT01ES k (^OetUtl^ j^tSir n P2MSE P©B EYERYB©BY ©ggjsiir Hsis si Swnffit MMifQiMdDininal !D)n§si[iP[p©ninittiniii©niitt On the Spur of 1 1 1 P.M- 1:30 ftwl 6 P-M the Moment '' BY ROY MOULTON. I DPP VSORRV, »l)T WE HAVE TO ANSWER G*7ouT) /A^l^^OeT^HARRlCD' Written Exclusively for Evening St»f. CD A j /b^ BRST I Hw/tcToet (CLOSE OP NOW, SIR. BY \ WILL WAY *S\R, VOO ARE THE t ( MY TROUSSSAU. Yo3 THE VIChTvANtS*ToAGCTFMA»»!lo -t ALONG ANO HELP /( THIRD -16NTLEMAN WHO HAs I'TIOM TUB IIICKUYVH.I* ci.ah.iox V Sg«T WAY. 1I AM ?i,«aleSL A (OO V J I He SELECT IT? S WAITED fW THAT SAME LADY, Blmer Jones Is dickerin’ with a fe<* j ^- °°MC SACK. ler for a plug hat and there la somn i \ HER/I^ V_J° tuik that he is goin’ into the under* takin’ business. O——O Ami- Hilliker traded off bis cheese an oatmobile and the next, V • factory for V day the oatmobile blowed up. Arne says there are times in a feller’s life when he cnn’t lay up a. cent, O-O The only thing on this earth that will stick closer than a brother Is the screw top on a glass fruit ,1ar. o—o There is several ways to eat sauer- kraut. but the best way is by proxy. O-O f never yit see a woman who would admit that she had anything to wear, and judgin’ by the statues in the mu, soums, I guess In the old days they really didn’t.