Cahiers Du Monde Russe, 52\/1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prelims Nov 2005.Qxd

German Historical Institute London Bulletin Bd. 27 2005 Nr. 2 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Stiftung Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. CLARISSA CAMPBELL ORR (ed.), Queenship in Europe 1660–1815: The Role of the Consort (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), xvii + 419 pp. ISBN 0 521 81422 7. £60.00 ($100.00) During the past decade the literature on women at the European courts has grown rapidly. Queenship in Europe 1660–1815 is a wel- come addition to this expanding field of research and it appears as a natural extension of Clarissa Campbell Orr’s previous volume enti- tled Queenship in Britain, 1660–1837 (2002). Queenship in Europe consists of a fine introduction by the editor and fourteen essays on various consorts and/or mistresses. After a brief overview of the volume, this review will focus on Campell Orr’s introduction and a few selected papers that exemplify the strengths of the collection and reveal some of the difficulties that arise when court history is combined with gender history. In the first essay, Robert Oresko traces the life of the powerful Maria Giovanna Battista of Savoy-Nemours (1644–1724) with an emphasis on her regency and her extensive building projects. -

Back on the Glory Trail Setting Sail Sea the Stars

SUNDAY, MAY 12, 2013 732-747-8060 $ TDN Home Page Click Here BACK ON THE GLORY TRAIL SEA THE STARS COLT SMASHES RECORD The sound of deflation following the defeat of Europe=s Breeze-Up carnival descended upon Saint- Toronado (Ire) in last Saturday=s G1 2000 Guineas Cloud yesterday and Arqana=s record book was torn could be heard far afield, but his less flashy stable asunder within the first hour of trade as a Sea the Stars companion Olympic Glory (Ire) (Choisir {Aus}) can put (Ire) colt, already named Salamargo (Ire), broke through some pep back in the step of trainer Richard Hannon if the half-million barrier to set a new benchmark when he can overcome a wide draw in today=s G1 Poule selling to Newmarket conditioner Marco Botti, acting on d=Essai des Poulains at behalf of Sheikh Mohammed bin Khalifa Al Maktoum, Longchamp. Tasting defeat for i520,000. Offered by Alban Chevalier du Fau and only once so far on only his Jamie Railton=s The Channel Consignment as Hip 13, second start at the hands of the February-foaled bay, who is out of the dual stakes Dawn Approach (Ire) (New winner Navajo Moon (Ire) (Danehill), returned a Approach {Ire}) in Royal handsome profit on the i200,000 he cost when Ascot=s G2 Coventry S. in passing through the Deauville ring at last year=s August Olympic Glory June, Sheikh Joaan bin Hamad Yearling Sale. AI have three juveniles by his sire with Racing Post Al Thani=s likeable colt seemed me, and he is probably one of the best I=ve seen,@ Botti to find winning coming easily told Racing Post. -

Aurora Ariel Pocahontas Belle Snow White Mulan Tiana Jasmine

(Sleeping Beauty) First princess to be physically injured by a villain – pricked her finger on Maleficent’s enchanted Aurora spinning wheel. Purest degree of all Princesses; first born daughter and only child of a King and married Prince Phillip. Not born human. Youngest of 7 children of King Triton. Became Princess Consort through marriage with Prince Ariel Eric and have daughter Melody. Eldest child of Chief Powhatan. The second princess (after Jasmine) to have a different singing voice than Pocahontas speaking voice. (Beauty and the Beast). First confirmed country France – all the previous princesses’ countries are inferred but Belle not confirmed. Off common birth, but became Princess Consort through marriage with Prince Adam. Snow White True princess, daughter of a King. Married an unnamed Prince. First princess to be based on a legend and not a fairytale. The only Disney Princess to date to actually hold no title Mulan of Princess in one form or another – not noble born and no titles of her own. Eventually marries General Li Shang (non-noble) (The Princess and the Frog) First African-American Princess. Closest story to recent times (set in New Orleans, Tiana 1920’s). Commoner born. Became Princess Consort through marriage to Prince Naveen, eldest son and Heir Apparent of the King of Maldonia. (Aladdin) Noble born. First born daughter and only child of the Sultan of Agrabah. Aladdin – commoner – gains Jasmine title Prince Consort through marriage. Cinderella Not noble born. Married Prince Charming. Have stepsiblings. First princess since Ariel to have red hair, also first Pixar Princess. First born of King Fergus of DunBroch, medieval Merida Scotland. -

Diplomacy World #131, Fall 2015 Issue

Notes from the Editor Welcome to the latest issue of Diplomacy World, the http://www.amazon.com/Art-Correspondence-Game- Fall 2015 issue. This is the 35th issue we produced Diplomacy-ebook/dp/B015XAJFM0 since I returned as Lead Editor back in 2007. It doesn’t really seem that long ago; it feels more like two or three Or there was a recent article in The Independent by Sam years instead of nearly nine. Kitchener which gave a fair and entertaining description of the game: The hobby was much different in 2007 than it was during my first term as Lead Editor (about ten years earlier) and http://www.independent.co.uk/extras/puzzles-and- it has continued to evolve during this stint. Sometimes I games/treachery-s-the-way-to-win-at-diplomacy-which- feel very connected to the hobby and what is going on, makes-it-just-like-the-real-thing-10485417.html and at other times I feel like I am completely out of the loop. New conventions, new websites, new hobby Both are recommended reading, by the way. groups…some of the older ones fade away and are replaced by new ones. But as I was saying, sometimes I feel a little out of touch. So I encourage each of you reading this to send me an email, even a short one. What I’d like are answers to a few simple questions: 1. I would like to see more of this type of article in Diplomacy World: _______ 2. I think Diplomacy World has too much of this type of article: _________ 3. -

ExperienceTallinn

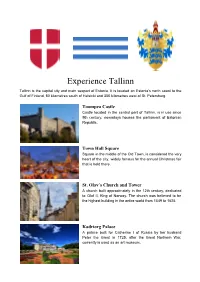

Experience Tallinn Tallinn is the capital city and main seaport of Estonia. It is located on Estonia's north coast to the Gulf of Finland, 80 kilometres south of H elsinki and 350 kilometres w est of S t. P etersburg. Toompea C astle Castle located in the central part of Tallinn, is in use since 9th century, nowadays houses the parliament of Estonian Republic. Town H all Square Square in the middle of the Old Town, is considered the very heart of the city, widely famous for the annual Christmas fair that is held there. St. O lav’s C hurch and T ower A church built approximately in the 12th century, dedicated to Olaf II, King of Norway. The church was believed to be the highest building in the entire w orld from 1549 to 1625. Kadriorg Palace A palace built for Catherine I of Russia by her husband Peter the Great in 1725, after the Great Northern War, currently is used as an art m useum. Town H all Pharmacy A pharmacy located on the Town Hall Square, which has been working continuosly since 14th century. Even nowadays one can buy any medicin needed from the pharmacy. Contains a little exhibition of different items used to treat diseases in the M iddle ages. St. A lexander N evsky C athedral The large and richly decorated Russian Orthodox church, designed in a mixed historicist style, was completed on Toompea Hill in 1900, when Estonia was part of the Czarist Empire. -

Russian Art, Icons + Antiques

RUSSIAN ART, ICONS + ANTIQUES International auction 872 1401 - 1580 RUSSIAN ART, ICONS + ANTIQUES Including The Commercial Attaché Richard Zeiner-Henriksen Russian Collection International auction 872 AUCTION Friday 9 June 2017, 2 pm PREVIEW Wednesday 24 May 3 pm - 6 pm Thursday 25 May Public Holiday Friday 26 May 11 am - 5 pm Saturday 27 May 11 am - 4 pm Sunday 28 May 11 am - 4 pm Monday 29 May 11 am - 5 pm or by appointment Bredgade 33 · DK-1260 Copenhagen K · Tel +45 8818 1111 · Fax +45 8818 1112 [email protected] · bruun-rasmussen.com 872_russisk_s001-188.indd 1 28/04/17 16.28 Коллекция коммерческого атташе Ричарда Зейнера-Хенриксена и другие русские шедевры В течение 19 века Россия переживала стремительную трансформацию - бушевала индустриализация, модернизировалось сельское хозяйство, расширялась инфраструктура и создавалась обширная телеграфная система. Это представило новые возможности для международных деловых отношений, и известные компании, такие как датская Бурмэйстер энд Вэйн (В&W), Восточно-Азиатская Компания (EAC) и Компания Грэйт Норсерн Телеграф (GNT) открыли офисы в России и внесли свой вклад в развитие страны. Большое количество скандинавов выехало на Восток в поисках своей удачи в растущей деловой жизни и промышленности России. Среди многочисленных путешественников возникало сильное увлечение культурой страны, что привело к созданию высококачественных коллекций русского искусства. Именно по этой причине сегодня в Скандинавии так много предметов русского антиквариата, некоторые из которых будут выставлены на этом аукционе. Самые значимые из них будут ещё до аукциона выставлены в посольстве Дании в Лондоне во время «Недели Русского Искусства». Для более подробной информации смотри страницу 9. Изюминкой аукциона, без сомнения, станет Русская коллекция Ричарда Зейнера-Хенриксена, норвежского коммерческого атташе. -

TSARINA Ellen Alpsten

Book Club Guide TSARINA Ellen Alpsten In brief Lover, murder, mother, Tsarina. Memoirs of a Geisha meets Game of Thrones in this page-turning epic charting the extraordinary rags-to-riches tale of the most powerful woman history ever forgot. In detail Spring 1699: Illegitimate, destitute and strikingly beautiful, Marta has survived the brutal Russian winter in her remote Baltic village. Sold by her family into household labour at the age of fifteen, Marta survives by committing a crime that will force her to go on the run. A world away, Russia's young ruler, Tsar Peter I, passionate and iron-willed, has a vision for transforming the traditionalist Tsardom of Russia into a modern, Western empire. Countless lives will be lost in the process. Falling prey to the Great Northern War, Marta cheats death at every turn, finding work as a washerwoman at a battle camp. One night at a celebration, she encounters Peter the Great. Relying on her wits and her formidable courage, and fuelled by ambition, desire and the sheer will to live, Marta will become Catherine I of Russia. But her rise to the top is ridden with peril; how long will she survive the machinations of Peter's court, and more importantly, Peter himself? Author Biography Ellen Alpsten was raised in Kenya. She won the Grande École short story competition for her novella Meeting Mr Gandhi while studying for her Msc in PPE, and went on to work as a producer and presenter for Bloomberg TV in London. She has written for Vogue and Conde Nast Traveller. -

Survey Report

YouGov Survey Results Sample Size: 1883 GB Adults Fieldwork: 29th - 30th October 2014 Westminster VI 2010 Vote Gender Age Social Grade Region Lib Lib Rest of Midlands / Total Con Lab UKIP Con Lab Male Female 18-24 25-39 40-59 60+ ABC1 C2DE London North Scotland Dem Dem South Wales Weighted Sample 1883 X X X X 580 442 381 913 970 224 476 644 539 1073 810 241 612 403 463 164 Unweighted Sample 1883 467 512 98 234 562 469 396 926 957 147 380 781 575 1285 598 218 605 402 479 179 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % May Oct 22-23 29-30 Thinking about the future monarch, which of the following would you prefer? Prince Charles should succeed as King after Queen 39 40 52 42 50 38 49 39 43 41 39 28 35 40 50 44 35 44 40 39 42 34 Elizabeth II Prince William should succeed as King after Queen 39 37 40 32 25 47 42 33 32 33 41 42 35 39 33 32 43 29 40 38 37 35 Elizabeth II instead of Prince Charles Neither - there should be no monarch after Queen 14 16 6 22 24 11 6 23 20 20 13 16 19 17 13 18 14 19 15 15 15 24 Elizabeth II Don't know 9 7 2 5 1 4 3 4 5 6 8 15 11 4 4 6 8 8 5 8 7 7 May Oct 9-10 29-30 2013 2014 Thinking about if Prince Charles becomes king, should his wife, the Duchess of Cornwall..? Become Queen 16 17 21 17 24 13 18 16 22 18 16 18 18 18 15 19 14 16 15 17 20 18 Have the title of Princess Consort 46 46 55 42 51 46 58 40 44 45 46 42 40 45 54 46 45 44 52 43 44 35 Not have any title at all 27 27 19 33 17 36 20 37 24 27 28 19 27 31 28 25 30 26 25 29 28 34 Don’t know 11 10 4 9 8 5 4 7 11 10 10 21 16 7 3 9 10 13 8 11 9 12 1 © 2014 YouGov plc. -

The Life of a Hard-Working Future King

The life of a hard-working future king His eccentric habits are known to the world, but the Prince of Wales has every reason to feel content. A man with wide interests and deep passions, he is finally happily married. Daniella Kent reports. Prince Charles is often portrayed as bad-tempered and spoilt. There are stories that every day seven eggs are boiled for his breakfast so that he can find one that is cooked just the way he likes it. His toothpaste is squeezed onto his toothbrush for him. And his bath towel is folded over a chair in a particular way for when he gets out of his royal bath. He has an enormous private staff – secretaries, deputy secretaries, press officers, four valets, two butlers, housekeepers, two chefs, two chauffeurs, ten gardeners, an army of porters, handymen, cleaners and maids. They are expected to get everything right. When HRH (His Royal Highness) feels they have performed their duties well, they are praised in a royal memo. But if they have made mistakes, they are called into his study and told off. The Prince can get so angry that he has been known to have tantrums, throwing things and screaming with rage. Headway Fourth edition Intermediate Student’s Book Unit 2, pp.18–19 © OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 2013 1 The private and public man Charles is eccentric, and he admits it. He talks to trees and plants. He wants to save wildlife, but enjoys hunting, shooting and fishing. He dresses for dinner, even if he’s eating alone. He’s a great socializer. -

RUSSIAN ART, ICONS + ANTIQUES Including the Commercial Attaché Richard Zeiner-Henriksen Russian Collection

RUSSIAN ART, ICONS + ANTIQUES Including The Commercial Attaché Richard Zeiner-Henriksen Russian Collection International auction 872 AUCTION Friday 9 June 2017, 2 pm PREVIEW Wednesday 24 May 3 pm - 6 pm Thursday 25 May Public Holiday Friday 26 May 11 am - 5 pm Saturday 27 May 11 am - 4 pm Sunday 28 May 11 am - 4 pm Monday 29 May 11 am - 5 pm or by appointment Bredgade 33 · DK-1260 Copenhagen K · Tel +45 8818 1111 · Fax +45 8818 1112 [email protected] · bruun-rasmussen.com 872_russisk_s001-188.indd 1 28/04/17 16.28 Коллекция коммерческого атташе Ричарда Зейнера-Хенриксена и другие русские шедевры В течение 19 века Россия переживала стремительную трансформацию - бушевала индустриализация, модернизировалось сельское хозяйство, расширялась инфраструктура и создавалась обширная телеграфная система. Это представило новые возможности для международных деловых отношений, и известные компании, такие как датская Бурмэйстер энд Вэйн (В&W), Восточно-Азиатская Компания (EAC) и Компания Грэйт Норсерн Телеграф (GNT) открыли офисы в России и внесли свой вклад в развитие страны. Большое количество скандинавов выехало на Восток в поисках своей удачи в растущей деловой жизни и промышленности России. Среди многочисленных путешественников возникало сильное увлечение культурой страны, что привело к созданию высококачественных коллекций русского искусства. Именно по этой причине сегодня в Скандинавии так много предметов русского антиквариата, некоторые из которых будут выставлены на этом аукционе. Самые значимые из них будут ещё до аукциона выставлены в посольстве Дании в Лондоне во время «Недели Русского Искусства». Для более подробной информации смотри страницу 9. Изюминкой аукциона, без сомнения, станет Русская коллекция Ричарда Зейнера-Хенриксена, норвежского коммерческого атташе. Мы представляем эту коллекцию в сотрудничестве с норвежским аукционным домом Бломквист (Blomqvist Kunsthandel AS) в Осло. -

Edinburgh University Library Handlist of Manuscripts

H21 The Dashkov medals Reference Code GB 237 Coll-21 Shelfmark or location Medals No. 119 In 1777 Princess Ekaterina Romanovna Vorontsova Dashkova arrived in Scotland with her son Paul (Pavel Mikhailovich Dashkov). Her son immediately began studies at Edinburgh University, and in 1779 the Princess, still resident in Edinburgh, gave a collection of Russian commemorative medals to mark the occasion of the graduation of Paul as a Master of Arts. The medals, over 150 in number and all made of copper, were entrusted first to Professor John Robison, Professor of Natural Philosophy in the University and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, who was instructed to make a catalogue of them. In the early 1770s, Robison had very briefly held the Chair of Mathematics in the Imperial Naval Cadet Corps at Kronstadt, where he had been given the rank of Colonel. The medals were only handed back to the University after Robison's death in 1805. If a catalogue was ever made by Robison it did not survive, and a proper catalogue of the collection still has to be compiled. Some of the medals show rulers of Russia, military figures, statesmen, events of the reign of Peter the Great. Others mark events such as coronations, accessions, marriages and deaths of Russian rulers. Imperial institutions are commemorated, as are cities and buildings of the Russian empire. Dashkova Medals: interim list Number Short title Description Diameter (mm) Material Notes DM/1 Andrei Alexandrovich Andrei Alexandrovich (1281-1304). 39 mm copper Language: Russian Obverse: bust of Dimitri Ivanovich. Reverse: Russian inscription. -

Fabergé in the Court of Siam

FABERGÉ IN THE COURT OF SIAM by Christel Ludewig McCanless and Annemiek Wintraecken Presented at the Symposium In Search of Empire: The 400 th Anniversary of the House of Romanov Columbia University, February 15-16, 2013 MAP PROVIDED BY GOOGLE AND ROUTE PROVIDED BY WIKIPEDIA Tsesarevich Nicholas Grand Tour to the Far East, 1890-91 31,000 total miles (51,000 km), including 9,000 mi (15,000 km) by rail and 13,000 miles (22,000 km) by sea St. Petersburg via Austria, Trieste, Italy, Greece, Egypt, India, Sri Lanka (Ceylon), Indonesia, Siam, French Indo-China (Vietnam), Japan, and Vladivostok (Eastern terminus of the Trans-Siberian Railway), across Siberia back to St. Petersburg • Fabergé objects totaling 15,500 roubles, replenished during the tour • March 20, 1891: Order of Chakri, highest order of Siam established in 1882, the year of the Chakri Dynasty Centennial Celebration to Nicholas • July 5, 1891: Russian Order of St. Andrew, Armored Cruiser Pamyat Azova equivalent to the British Garter from Emperor 385 ft. long, 6,674 tons displacement (Wikipedia) Alexander III (1845-1894) to King Chulalongkorn (Rama V) • November 1891: Order of Chakri to Emperor Alexander III with a letter of intent to further develop friendly relations with Russia Memory of Azov Egg (1891) by Fabergé Bloodstone, miniature is less than 3 inches Gifts (orders not by Fabergé): Badge of the Order of St. Andrew Christian Pendant and Symbols Star of Order (Sotheby’s) of Chakri (Wikipedia) 1891 (left to right) Crown Prince Maha Vajirunhis (died at age 17), Tsesarevich Nicholas, King Chulalongkorn (Rama V), Prince George of Greece and Denmark, Prince Chaturanta Rasmi, younger brother of the King.